The 2015 AIPC-ZAM Investigations

Witches are real. They exercise political power in West African societies

Witchcraft pervades some developing societies up to the highest levels with devastating effects. Demonic spells, marketed as miracle cures that give wealth and power, strengthen those who wield them most violently and disempower everyone else. Once part of a spiritual belief system at the service of communities, the practice is now owned by secret societies that operate like mafias. A report from a universe where politicians are held hostage, cult militias are ‘stakeholders’, people are killed for their body parts and citizens are afraid to move.

YAOUNDE, CAMEROON, 1 FEBRUARY 2016

When Cameroon’s President Paul Biya calls on his country’s villages to ‘use witchcraft’ to defend themselves from Boko Haram invaders from Nigeria, critical intellectuals make fun of him on Twitter. ‘Desperate times, desperate measures,” tweets one. Another asks if the President is now ‘Head witch-crafter in charge.’ “Biya’s only legacy is corruption and witchcraft,” is, in a reference to the country’s pathetically weak state, the verdict of a third one.

But calling on witchcraft for ‘empowerment’ is by no means exceptional in Cameroon and its West African neighbours. In Nigeria, too, in 2014, villagers were reported to use ‘enchanted bees and snakes’ to chase Boko Haram militias out of Sambisa forest. (On Twitter, Nigerians joked -in a reference to the fruity candy-, about ‘jujubees,’ juju being the Nigerian term for witchcraft.)

Such reliance on an ages-old, strong spiritual belief system -in which ancestors provide guidance through ‘initiated’ leaders, and trees, plants and rocks are thought to be infused with ‘spirits’-, as a ‘weapon’ with which to harm one’s enemies, seems to have increased, rather than decreased, in (West) African countries in modern times.

This may have something to do with colonial history. Whilst in the past three centuries Europe was building own states inhabited by increasingly empowered citizens, African countries were subjugated by foreign powers. Spears and sticks being rather useless against (western) guns, some historical anecdotes refer to Africans using witchcraft in attempts to chase colonizers. In the 19th century, rural townsfolk in Nigeria once successfully invoked spirits to remove foreign oil prospectors from their region (more about this below). SA President Jacob Zuma famously said that before he joined the armed freedom struggle, he used to ‘practice witchcraft against white people’ during the days of apartheid (1).

Remarkably, the use of the witchcraft ‘weapon’ has not abated in the post-colony, where even a present-day government leader like Paul Biya seems to believe that charms and potions can defeat an invading army. Which begs the question how he as President perceives the capability of his own state. The answer is probably: as not much. “The French gave us a state machinery to run,” he is famously reported to have said once. “But they didn’t tell us how.”

NKOLANDOM, CAMEROON, MARCH 2015

Two youngsters from Nkolandom village in Cameroon’s rural south are successfully admitted to study International Relations at the exclusive International Relations Centre (IRIC) in the capital Yaounde. The privilege –IRIC is posh, and they get bursaries- has been granted to them by education minister Fame Ndongo, who has irregularly added the two to an already approved list. Ndongo’s fraud is discovered by media in Cameroon, who call for sanctions. But President Paul Biya accepts the additions and refuses to punish Ndongo. The reason: a threat of witchcraft.

Minister Ndongo is originally from Nkolandom. According to press reports, he had during a visit back to his ancestral grounds two years ago been warned by local Chief Assam Otya’a, that “he should not forget his clansmen in the area” and that it was “thanks to the intervention of his own people that he had been a Minister for so long in the Biya government”: a thinly veiled reference to local witches’ support for Ndongo’s career. The Chief told Ndongo to show‘gratefulness’ by now helping village youth to advance their careers.

It took Ndongo two years to pay this debt, but when he did, he probably knew he would get off scot-free. The President, who is from the same ethnic community grouping as Ndongo, would not risk angering the witches any more than he would. Says a traditional leader from the same area: “Surely he (Biya) knew what also awaited him if he failed to let the two candidates of the minister to enter the school.”

KANDUNA, NIGERIA, AUGUST 2015

“They call themselves stakeholders”

A politician in Kaduna state confirms that, he too, is threatened by witches. They have already put spells on him before, he says. “One morning I woke up with bad odour in my mouth and terrible breath. Later on, some mornings, I found my mouth was bleeding for no reason. I wanted to stand for local elections. But the affliction chased all my followers away.” He points at a bird perched on an electric pole nearby. “It is a hawk, see? It is one of three birds an eagle, a dove and this hawk. They are sent by my enemies to keep an eye on me. Because I have decided to stand for elections again.” He takes witches’ power very seriously. “My brother, a council chairman, died under suspicious circumstances.”

The only way to survive, and survive politically, is to strike deals with the groups -called ‘cults’- who use witchcraft to sabotage, blackmail and extort, he adds. “If you are on good terms with such a clique they will protect you and work for your success. But as soon as you don’t do their bidding they have a way of dealing with you. Whatever you possess you will lose.” In the local government area where he aims to get elected, he says, “I must provide some percentage of the council’s monthly allocation and give to them. They call themselves stakeholders.” Save for the witchcraft element, what this politician describes sounds just like an ordinary gang that charges ‘protection fees.’ Nevertheless, it is the ‘demonic’ power they claim to have that inspires his massive fear.

Whether the ‘percentage’ claimed by the witches comes from his pocket or from state funds meant for public services, he doesn’t say. But the use of state funds to buy favours and pay-back ‘protectors’ –including witches’ cults- is common in Nigeria’s corrupt bureaucracy. In 2009, the chair of the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), Sam Edem, was suspended after it was found that he had used more than 200 million Naira of the NDDC’s money to pay off a witch doctor who had allegedly helped him to obtain lucrative contracts and increase his sexual potency (Edem denied the bit about the potency, but not the rest.)

More recently, in April 2015, the then ruling (now opposition) PDP party recruited ‘cultists’ in Rivers State –this particular group being both an oil rebel militia and a witches’ cult, - to ensure a victory in the governorship elections in that state. The group then became more than a mere ‘stakeholder’ in the state government. ‘Ten members achieved MP seats,’ a commission of enquiry wrote in their report on the matter in July last year. (2)

Magical mafias

It could perhaps be argued that the use of witchcraft to secure a ‘stake’ in power is the only way to derive some benefit from a seriously corrupt state that otherwise does very little for its citizens. A traditional ruler from the Obang area in Cameroon explains that witchcraft can indeed be used by people who regard themselves as neglected or victimised. “The rich are getting richer and the poor poorer. Some (people)are angry with society because of the raw deals they have been cut. They resort to witchcraft to punish their Nemeses.” The ruler doesn’t approve of those who do this. But “a drowning person can cling to even a snake to remain afloat,” he says.

Cameroonian sociologist Eric Kombey puts the blame for people’s grabbing at the straw of magic squarely on post-colonial governments. “African regimes have failed their citizens,” he says. “With the spiralling tendency towards bribery, corruption and greed, those who are not in positions to acquire the good things in life turn to witches and wizards in the hope of being helped to arrive.”

It would perhaps be nice if ordinary citizens in general could, in fact, be ‘magically’ empowered to assert their rights. However, in the three investigated countries, the deadliest ‘witchcraft’ force was found to be wielded by the most ruthless criminals, willing to terrorise, kill and inspire deadly fear in the pursuit of power. Belief in magic on an individual level usually doesn’t extend beyond the consultation of a marabout, or the purchase of a charm to protect one’s shop. But serious witchcraft cults, -like the militia in Rivers State-, behave more like murderous mafias. The discovery, in 2014, of a hide-out in Ibadan forest, east of Lagos, where skulls and bones were strewn around a ‘slab’ where victims’ bodies had been cut to pieces –to be sold as strong ‘muti,’ medicine that will infuse the buyer with wealth and power- led to the discovery of a gang that kidnapped people for ransom, robbed them of their possessions, occasionally raped and tortured them and only then murdered the ‘unpaid for’ survivors for body parts sales (3).

In Cameroon a young man was arrested with the severed head of his own father.

Human body part ‘muti’ is a money-spinner in organized crime circles in West Africa. The powerful and wealthy pay a lot for such ‘extra strong’ muti -in their case not to obtain a stake, but to keep it. “Those who have already arrived, wanting to maintain their high standards of living, believe only witchcraft can help them remain within the council of the overlords,” says sociologist Eric Kombey. Believing they owe their status and wealth to witches rather than to capability and skill, they continue to pay for more and more ‘protection.’ In Cameroon, in 2014, a young man was arrested with the severed head of his own father. He claimed a politician had promised to pay him US$ 30 000 for it (4).

Doom shall befall the prospectors

Ever since foreign oil prospectors, alerted by missionaries to the presence of rich crude oil deposits, were “warned against the wrath of the gods of the land” by the villagers of Ugwulangwu in South East Nigeria if they were to tamper with the wealth underground, industrial and developmental projects have been halted by ‘spirits.’ The successful chasing of the colonial prospectors from the Ugwulangwu area –confirmed to the team in hushed tones over the phone by a present day inhabitant - may have been beneficial to the locals at the time. But the invoking of spiritual powers to stop projects, some of which could arguably bring real development instead of plunder, continues until today.

It was, for example, only around the 1990’s that electricity came to Obehiri village in Kogi State, North-Central Nigeria. The development had been delayed for years because of a certain ‘holy’ tree that would need to be cut. The linking of two main roads in Kaduna city because of a ‘holy’ heap of rocks separating the roads was delayed until 2007. And up to today, the Niger Delta is riddled with random stretches of road and half-built structures, either actively sabotaged or abandoned by ‘stakeholders’ who only cared about their ‘stake’ and not about development.

Benin shows a similar landscape. “Projects fail terribly. There is sabotage of your construction materials from the start. I am aware of a case where a supervisor over a roads project was killed,” says a manager of an international NGO in Parakou. “This is why people are scared to start businesses.”

Cameroon’s recent history, too, is littered with projects that failed because ‘witches’ felt that they didn’t get their share. Most prominent among these is a celluloid-from-wood factory in Edea, not far from the country’s coastal second capital, Douala. Started in the seventies of the last century, there was to be industrial activity here, a boost to the economy, jobs. But as it happens in Cameroon, locals were not compensated for land taken from them for the development. With the citizenry suitably angry, “rogue local officials connived with native witches and wizards to frighten the (western) investors away after embezzling the part of the money intended as state participation in the project,” remembers an elder in Edea. “There were explosions and deaths and later the director died in a boating accident. The witches boasted that they did him in.”(5) An attempt to revive the factory during the nineties also came to nought because of, in the words of the Edea elder, “a mixture of official corruption and witchcraft.”

Blurring the auditor’s vision

Witchcraft, having become a means and an instrument to secure a profitable ‘stake’ in the state, is also marketed as a means to ‘blur the vision’ of an auditor or corruption investigator. The liquidation of the Credit Agricole du Cameroun (CAC) in 2007 victimised over 4,000 rural Cameroonian farming families who had invested their savings in the bank. The bank had promised the farmers that it would multiply their savings and also grant them loans for small businesses. Instead however, the moneys were siphoned off in ‘loans’ to a number of ruling party, army and government bigwigs under ‘assurance by ruling party members that witches would hide (them) from the auditors.’ By the time the Credit Agricole went down in 2007, the bank owed its customers a total of 57 billion FCFA (about US$ 314 million)(6). Says a source in the Ministry of Finance “this was perhaps the only bank in the world where witchcraft, or the threat of it, served as collateral for big government and ruling party officials to borrow large sums of money with the knowledge they would never pay back.”

Save for one individual liquidator called Ekande Frederic (7) who was later convicted for fleecing the leftovers of the bank, the ruling party members who stole the funds have never been brought to court. “But our members have died without collecting a franc of their savings,” says Nloga Simon, a member of the CAC Clients Association. “Most of them have lost family members. Children have dropped out of school. We don’t even come to see the liquidators anymore because we have been told the same story for over seven years now.”

A paralysed society

Scared of angering witches, shopkeepers in Benin routinely protect their small business with charms bought from marabouts. Nobody wants to be seen to be too successful though; where power is seen to come from unseen forces and control is exercised by secret groupings, it is best not to attract attention. It is not just that one might anger witches by being successful; one might also be suspected of being a witch oneself. There are plenty cases of individuals accused of witchcraft and lynched, or chased into special ‘witch villages,’ or locked into police custody for their own safety. “There is never any evidence to buttress accusations of witchcraft,” says barrister Ojong-Mfung in Buea, who has defended suspects of witchcraft crimes –in Cameroon, these cases amount to several hundred each year- in his regional court. “This leads then to lynching.”

The ones to profit from witch-hunting, are again, witches themselves: ‘good’ witches, or, in Benin, voodoo priests and marabouts. These make their money from ‘sniffing out’ bad witches, protective charms, and exorcisms. During our investigation, for example, a woman in Cotonou had her ‘demonic’ pregnancy terminated by a marabout who proudly presented a picture of a rather large fish as proof that the ‘demon’ had been successfully removed. The team was also told on numerous occasions of ‘bewitched,’ children, submitted to excruciatingly painful and expensive exorcism rituals conducted by so-called healers, both in Nigeria and Benin.

In the end, maybe it doesn’t matter if someone is a good or a bad witch. Placing one’s fate in the hands of an outsider rather than in own skill and capability, will arguably always disempower rather than empower the individual. “Tell me, what can a teacher who failed her examination for four years running and only passed it through witchcraft, teach her own students?” asks an inspector in Cameroon’s education ministry in relation to rampant cases of ‘diploma buying.’ And University of Dschang don James Nchare, citing the gruelling case of a female secondary school student who killed her own mother so that the mother’s blood could be used for a potion ‘to make her pass the exam,’ says he has noticed a drop in education standards because of witchcraft.

Meanwhile, in the seaside town of Limbe, also in Cameroon, tax money hasn’t been put to good use for years. Elections are pervaded with witchcraft allegations; both ruling and opposition party pocket citizen’s money whilst accusing one another of using ‘unorthodox means’ to win. The badly needed market, a project decided and paid for in 1988, has never been built.

LIMBE, CAMEROON, 2015

Hunting the witches

But change may also be underway. Whereas there are more and more groupings using the ‘craft’ as an instrument to extort and threaten, these are increasingly recognised as‘fakers,’ says ‘Benjamin,’ an initiated ‘good witch’ in Manyu. He likens these fakers to ordinary criminals and says some have already been killed by “authentic witches and wizards who perceive these quacks as polluting their trade.” Sociologist Eric Kombey feels that a recent increase in lynchings of ‘witches’, such as in Buea in 2014 (8) are symptomatic of a society that is tired of fear and cowering. “Whereas in the past, for fear of being bewitched to death, local communities would hardly rise up against accused witches, it is becoming more and more rampant to see street crowds lynching those accused of the evil practice. If this continues, as it is surely doing, then positive change may be in the offing soon.” It is surely the first time anybody in recent history has gone on record to defend a witch hunt.

Developing the Delta

Even in Nigeria, slowly, signs of change are emerging. A number of ‘clean’ appointments by new president Muhammadi Buhari, -who won the election with his APC party on an anti-corruption ticket-, has sent shockwaves through a number of ministerial departments. And through the corrupt, witchcraft-ridden structures of the Niger Delta.

For development in the Delta, the same region where ten cultists were elected MP’s in 2015 and where a former Development Commission boss once defrauded his structure to pay a witch-doctor, is now in different hands. The newly appointed CEO of the Niger Delta Development Commission is Ibim Semenitari, -a member of new ruler Buhari’s APC party and a former investigative journalist-, who is known not to have any sympathy for cults, mafias, individual witches or any other illegal ‘stakeholders’ in politics. At her instatement in December 2015 she stated in no uncertain terms that from then on, “(developmental) projects (will be) inspected before we pay contractors and only jobs verified and certified to be good will be paid for” and that “those who don’t do their jobs well should be ready to face the consequences.”

Semenitari had already experienced the wrath of the PDP-militias-cultists alliance in the Delta when she served as a commissioner (a local minister) in Rivers State until last year. Upon leaving the post to take up the NDDC job, her car was impounded and confiscated by a local (PDP-aligned) governor; she faced harassment and corruption accusations in trying to get it back; and was generally exposed to much unpleasantness.

On 16 February 2016, local APC chairman Davies Ikanya reported that twenty-six of his party’s members in Omoku town in Rivers State had been murdered –and some also beheaded- that week by the same Icelander militia-annex-cult that was earlier implicated in pro-PDP election violence. Ikanya alleged that meetings had taken place between the ‘Icelanders’ and the local PDP leadership to plan the killings (9). Police, however, blamed a fight between two cult groups for the massacre and the Rivers State Commissioner for Information, Austin Tam-George, declined to respond to the allegation that the PDP collaborated with the cultists, saying that to comment on it would be to ‘dishonour the dead.’

ACCRA, GHANA, 20 JANUARY 2016

A team meeting of AIPC team members Chief Bisong Etahoben (Weekly Post, Cameroon), Alberique Houndjo (Canard du Nord, Benin), Fidelis MacLeva (Daily Trust, Nigeria) and Anneke Verbraeken (freelancer, NL) decides not just to write a report on their investigations of witchcraft in Benin, Cameroon, and Nigeria. “It is bad. It must end,” says Chief Bisong, who is –as a traditional leader himself- eager to see a modern democracy evolve in his country, Cameroon. ('Chief' has always maintained that the best way to end witchcraft is to ensure that democratic structures work normally "so that nobody has any need for unorthodox means –they can just vote.")

Fidelis MacLeva, who has personally experienced the damage done by (belief in) witches’ curses, and who has become a devout Christian in order to fight this darkness, concurs: it is not enough to just write a story. There has to be an appeal. Anneke Verbraeken has felt the need to break the silence around witchcraft ever since she saw how it, and the fear created by it, damaged social life and progress in the towns where she has reported, in Benin, since 2013. And Alberique Houndjo, from Benin, feels shaken, too. “We always accepted it,” he says, but concurs. “No more.”

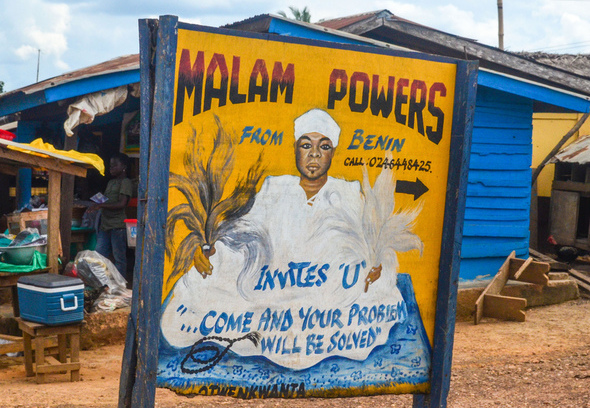

Photo: Voodoo Fetish Market, Lomé by Paul Williams/Flickr

Notes & bibliography

(1) http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2536513/South-African-president-Zuma-reveals-used-practice-witchcraft-against-white-people.html.

(2) https://www.documentcloud.org/search/Project:%20%22TI%202015%20Witchcraft%22

(3) http://allafrica.com/stories/201404071117.html

(4) The identities of the politician, the late father and the son are known to the AIPC team.

(5) Former Cellucam manager Matthias Ladurned later responded in a letter to a media report in Cameroon about this that the director, Horst Melzer, had died of cancer and not in a ‘bewitched’ boating accident as claimed. www.camerlinked.com/index.php/actualites/l-affaire-cellucam-suite-et-fin

(6) www.cameroon-info.net/article/credit-agricole-du-cameroun-le-tribunal-criminel-special-enquete-sur-la-faillite-184743.html

(7) http://allafrica.com/stories/201601201119.html

(8) http://observers.france24.com/en/20140113-witch-hunting-turns-violent-cameroon

(9) http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/198721-tears-sorrow-blood-rivers-community-cultists-kill-behead-residents.html