Cabo Delgado, 2021. Over 600 000 people, more than a quarter of the population, live in refugee camps, battling food and water shortages, mosquitoes, and disease. The Mozambican province has been under attack from violent militants – Ahlu Sunnah Wa-Jamo, or the local ‘Al Shabab,’ as residents call it – since August last year. Humanitarian aid organisations like Doctors without Borders barely cope, especially now that the pandemic is spreading and people present with cough, fever and shortness of breath. ‘We are seeing an increase in the number of cases with severe respiratory infections that we cannot identify as COVID, or some other infection, because there are no tests available (…),’ in the words of the organisations’ communications officer Amanda Furtado. ‘And some areas are so isolated that if we have a patient with severe symptoms, the nearest COVID hospital can be up to ten hours away by car.’

The nearest COVID hospital or treatment centre would be in Cabo Delgado’s capital, Pemba. But, unless you are connected, or agree to pay for what should be a free service, people here are sent away with a curt ‘the free tests are finished.’ Amade Abdul (name changed upon request), an inhabitant of Pemba, says he was lucky that his mother-in-law works at Pemba hospital. ‘At first the hospital lab technician did not want to use a test on me, saying that it ‘belonged to an adjacent private clinic’ and that I needed to go there (and presumably pay money, EV). I said I would not do that because I felt really ill. It’s only when my mother-in-law went to fetch another lab technician from upstairs that I got the test.’

Abdul feels fine now, he says, ‘but I have cousins and friends who are sick. They cannot get the test at the hospital and they don’t have the money to pay privately. They have come here but were told to go home. So, they are at home, eating ginger biscuits’.1

They have come here for tests but were told to go home

A budget of US$ 670 million, paid for by Mozambique’s development partners – inter alia the IMF, the World Bank and the EU – has been donated for emergency COVID 19 relief in the country’s eleven provinces. But we cannot find any goods or services brought to Cabo Delgado with that money. Two health centres and a COVID 19 testing lab were recently built and equipped in Pemba, but these have been the work of NGO’s: the health centre of 144 beds in nearby Muxara in the south of the capital has been built by Doctors without Borders together with the Red Cross. The director of Cabo Delgado’s main Pemba Hospital, Antonio Carvalho, confirms in an interview that the extra 32 beds and a lab that his hospital boasts ‘for COVID 19’ have been donated by oil and gas companies Total and Eni.

Provincial authorities

Hospital director Antonio Carvalho seems unaware even of the COVID aid budget’s existence. In an interview he laments the ‘scarcity’ of supplies such as masks and gloves and explains he has no idea how much in terms of material supplies his hospital is supposed to receive anyway. ‘There is a ‘provincial distribution plan’ but we don’t know what portion from that plan is allocated to the hospital’, he says. ‘We just receive some supplies on a monthly basis, which we sign slips for. For further information you should ask the provincial authorities.’

The provincial spokesperson for Cabo Delgado also seems unaware of any emergency COVID budget for the country, let alone this province. ‘We just have goods and services provided by developmental NGOs, like Doctors without Borders and the Red Cross’, says the spokesperson, Sumali Gilberto, in an email. He mails again later: ‘Of course I am not well informed about health. Please engage with the relevant people.’

The relevant people – that would be provincial health minister Anastacia Lidimba. We would like to talk to her about a particular budget of US$ 2.39 million that, according to a financial report from the Ministry of Health, should have been made available to the provinces. It is not much, but surely Cabo Delgado should have received at least some of that? But Lidimba postpones interview after interview and in the end outright refuses to talk, saying that she needs ‘authorisation’, from the health department in Maputo, to do so. We approach the Health Ministry in Maputo a number of times, by email, phone and WhatsApp, but never hear back.

This is a pity. Because Anastacia Lidimba’s signature is on a contract for ten million, two hundred thousand Meticals, roughly US$ 172 000, for three COVID 19 training workshops, held sometime between July last year and now, at the Sarima Hotel in Pemba, Cabo Delgado. We have found this payment in the section ‘Cabo Delgado’ on a ‘Mapa de Empresas’ list of companies that have been contracted to provide goods and services in exchange for COVID funds. The total services contracted for Cabo Delgado amount to US$ 191,000, which corresponds to the share the province could have received from the provincial US$ 2,39 million COVID budget.

The rest stayed with the provincial directorate

According to the company contracts list, US$ 191 000 for Cabo Delgado has been spent on the VIP Spar Supermercado (US$ 17 000) and petrol (US$ 2 000), besides the US$ 172 000 paid to the Sarima Hotel for the three workshops. ‘Oh but we did not receive all that money,’ Anifa Gonzaque, Hotel Sarima’s manager, explains when we pass by to ask. ‘We only received twelve percent. The rest stayed with the provincial directorate.’

Twelve percent, over US$ 20 000, is still a lot of money for three workshops: according to the hotel’s price list, one workshop will be catered for 20 000 Meticals (US$ 340). ‘But we give them the full package for 30,000 Meticals, (US$ 500),’ says Gonzaque. ‘And it is a year long contract and the idea is that they just come and have workshops when they want.’ She emphasises again that the hotel has come nowhere near the full amount of the US$ 172 000.

As far as we can establish, only provincial health director Anastacia Lidimba and perhaps a few colleagues know what has happened to that full amount. We send questions and wait for comment, again.

VIP Supermercado

That, except for Hotel Sarima, the VIP Supermercado and a certain petrol station, none of the US$ 670 million emergency COVID relief has reached those who need it in Mozambique’s tormented Cabo Delgado province is not really a surprise to citizens here. In this country one must be connected to ruling party networks to get any public service, like health; this has particularly always been the case in this resource-rich region. Cabo Delgado’s villages have experienced rough exploitation and plunder, dispossession and forced removals of farmers, fishermen and artisanal miners for decades now. Gemstones, wood, oil, fish stocks and wildlife have been appropriated by politicians, bureaucrats and ruling party officials; police and militias with guns and machetes have been unleashed on communities who stood in the way.2

Indeed, this history is at the root of the current insurgency3, even if the militants ideologically profess to be Islamic fundamentalists. The ‘local Al Shabab’ says in its propaganda that ‘Allah wants a society where we all share and live together in peace.’

In the upper-class suburbs, people are very happy

The reality of Cabo Delgado is literally thousands of miles away from the capital Maputo’s Sommerschield area where the upper classes live amid embassies, gelaterias and cocktail bars. The Polana Caniço Hospital is here, right between Julius Nyerere Avenue and the golf club. The clients who visited this hospital for COVID tests and, where necessary, treatment, are all very happy with the service they received here, headlines a recent article in the capital-based ‘Club of Mozambique’ newsletter.4 The funds required for this service have indeed come from the COVID 19 aid budget, as a recent report from Mozambique’s Ministry of Finance shows: Polana Caniço received no less than ten million US dollars to prepare this particular hospital to deal with the pandemic. It is the only hospital mentioned in the Ministry of Finance’s entire US$ 670 million COVID expenditure report.

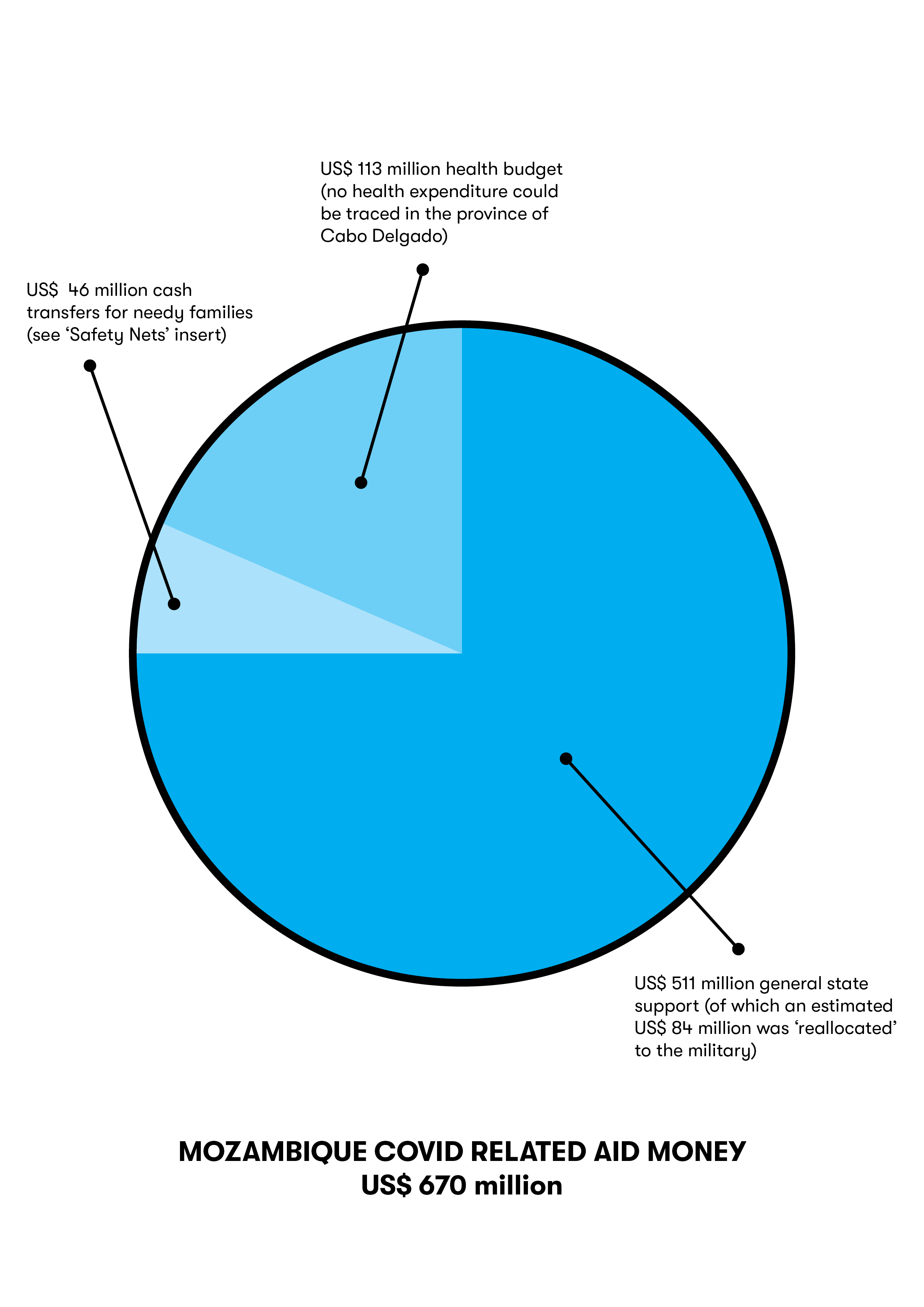

For the rest, we learn from the same report, dated 31 March 2021, that by far the largest part of the received money, US$ 511 million, was allocated to make up for the deficit in the general state budget ‘because there is a risk of lower revenue as a result of the COVID 19 pandemic,’ the document states. The report also shows that the amount dedicated to prevention and treatment of COVID 19 in the whole of Mozambique has been less than a quarter of this: US$ 113 million.

We could not trace most of the expenses of this budget, of which slightly less than half was received in kind (ie goods like tests and masks), but the ‘Mapa de Empresas’ contracted companies list shows where at least US$ 35 million went. Besides the US$ t0 million that went straight to the Polana Caniço Hospital in Maputo, US$ 22 million was spent on a few dozen contracts for service providers elsewhere. On paper, the contracts were for medical equipment and construction or improvement of health facilities, but also for training events, jingles, commercials, airtime, hotels, workshops and catering, mostly in the capital Maputo. The list includes an event for the Ministry of Health in the city’s Hotel Atlantis, billed for US$ 170 000.

In the end, the countries’ ten other provinces got slightly over US$ 3 million altogether. This included the US$ 191 000 we found allocated to Cabo Delgado.

An event in the Hotel Atlantis was billed at US$ 170 000

A closer look at the contracts in the provinces reveals that Cabo Delgado is no exception when it comes to the provinces. Outside Maputo, practically no health supplies were bought at all. Save for the construction of one health centre in Tete province for the equivalent of US$ 250,000, and several purchases of soap, all items are described as ‘lodgings,’ ‘food’ and/or ‘training workshops’, sometimes for health workers but most often for unidentified persons. The US$ 172 000, that we found spent on three workshops in Cabo Delgado pales in comparison to the ‘meals for officials’ billed at US$ 299 000, in Gaza province, as well as to the US$ 455 000, that went on ‘lodgings and food’, without any further description, in Nampula (compared to that expenditure, the item of US$ 2000 for three ‘training events’ in Zambezia province starts sounding like a really good deal).

Budget support

General state budget padding by development partners is a regular occurrence in most African countries. Mozambican analysts concur that, although US$ 511 million for the state itself is a bit much when the entire COVID budget is US$ 670 million, the pandemic would certainly cause a dip in an already battered budget, and some general support would be in order. The extraordinarily large amount of padding does, however, raise the suspicion that in this country’s case the army could be one of the main recipients of such designated COVID funds. More especially, the army that is currently fighting an insurgency in Cabo Delgado.

The Ministry of Defence is certainly the department with the biggest deficit. In August last year an expenditure report from that Ministry5 sounded the alarm in this respect: it had spent its entire US$ 168 million annual budget already in June that year, leaving a deficit of half that amount and nothing left to continue to fight the jihadi militias in the north. But in February and March 2021, months after receiving the COVID emergency budget from the donors, the ministry purchased several millions worth of new army helicopters, armoured vehicles and guns from South Africa.6

In questions sent to the Finance Ministry, we asked to what department or departments in government the US$ 511 million ‘general budget support’ were allocated, and if Defence was one of the recipients. We specifically also asked questions about some minor items in the general support budget that seem to connect to the Cabo Delgado situation. For example, why, from a smaller budget for general ‘assistance to municipalities’, there is a provision of US$ 52 000 for the village of Mocimboa da Praia, which has been in the hands of the insurgents’ forces since last August? Surely, Mozambique is not handing COVID 19 emergency funds to terrorists? Would it perhaps be used to try and take the town back from them?

Financial Ministry spokesman Alfredo Mutombene confirms that the defence budget has been ‘extended’ recently, through ‘internal reallocation’. He won’t say by how much, but the deficit of half of the 2020 annual budget, US$ 84 million, has – judging by the recent multimillion dollar purchases of weaponry – clearly been compensated for. For the rest, with regard to any of the used COVID funds, Mutombene says that ‘these are allocations, not monitored and evaluated funds. We’ll have to wait for the state internal audit and then the external audit of government expenditure before we can say how these moneys have been spent.’ With regard to our questions about the health budget, he suggests we speak to the ‘relevant sectors.’

We will email and call the Ministry of Health, both centrally and in the province, still many times. But neither provincial health director Anastacia Lidimba, she of the signature on the payment of US$ 172 000 for three workshops, nor central Health Ministry spokesman Nelson Belarmino ever respond.

A free test for fifty-five dollars

Back in Cabo Delgado, we buy a COVID test from the storage facility in Pemba hospital for 2 500 Meticals (US$ 55), a set of plastic gloves for thirty-three-dollar cents, a plastic oxygen mask for a dollar and a visor for fifty dollar cents. Just outside the hospital, the same items are for sale, for everyone to see. It is difficult to believe that director Antonio Carvalho, who told us that his ‘security guards and cameras never caught anyone’ stealing, never saw this. But who is surprised? Carvalho also never knew how many supplies were coming in or not. And if the Ministry of Health doesn’t care what happens in the provinces, why should he?

Later, we ask Amanda Furtado of Doctors without Borders if her organisation, in the absence of any COVID tests in the refugee camps, perhaps has asked the Mozambican government to help provide such health supplies. She responds in an email saying that the organisation must use ‘own supplies,’ even if, she also notes, it takes months for these supplies to arrive because of bureaucratic obstacles with importation. Asked if she doesn’t feel like protesting the disappearance of the government’s COVID moneys and goods, the response is curt: ‘We are a medical-humanitarian organisation and our activities are privately financed, independent and neutral MSF. (...) we cannot answer your question since it falls outside our area of specialisation.’

Notes

- Ginger is widely believed to help fight off COVID 19.

- See: The Associates | Mozambique – Licensed to plunder; The Ruby Plunder Wars of Montepuez; Friends with the General; Bad boys don't sleep

- See: A More Complex Reality in Cabo Delgado.

- See: Covid-19 Maputo survivors tell their stories, praise the work of Polana Caniço – Carta de Moçambique.

- See: Mozambique: Defence has already spent 95.5% of its annual budget – Carta.

- See: South African armoured vehicles spotted in Mozambique; Gazelles delivered to Mozambican Air Force.

The Safety Nets

Cash transfers form part of most COVID relief packages because people, especially in poor communities, are at high risk of losing their jobs due to lockdowns. Also, if you want people in poor areas to stay at home and not go out to work, it makes sense that they should be assisted to buy food in their neighbourhoods. Which is why, in the case of Mali, a large part of COVID relief funds donated by development partners, US$ 186 million, was put into the Jigisemijiri ‘Safety Nets’ government programme while in Mozambique US$ 46 million was added to the Institute for Social Action (INAS)’s family cash transfer budget. In South Africa US$ close to US$ 1.8 billion extra in COVID relief grants, funded with the help of an IMF relief package of US$ 4.3 billion, was allocated for distribution to the country’s social welfare agency, SASSA.

These programmes, like many such in African countries, existed already pre-COVID because of an increasing international consensus that giving cash to the poor helps to make a dent in poverty. Reportedly, most poor households make good use of even a little bit of support, for example in terms of working land and schooling children. Even more such support is obviously needed in a pandemic, or in other emergency situations, like the recent floods and droughts in Mozambique.

Lack of monitoring

Our reporters in Mali and Mozambique however, found no people to whom any monetary help was paid; not pre-, and not during COVID. This is probably partly because such programmes, conducted in states with little capability, generally reach a very small part of the poor to begin with. (In an example from Ghana, a country with a population of over thirty million of whom about fourteen million live in poverty, just over 200,000 households there are registered for small cash injections through the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) programme. A recent report from Ghana’s rural Mampong community, which is supposedly covered by LEAP, calculated that only seventeen percent of pensioners in the area actually received the LEAP support.1

In Mali, it is uncertain whether its cash transfer Safety Nets programme ever reaches any poor households at all. Around 120,000 households – out of over ten million poor – are registered, but a recent report2 on the efficacy of the programme mentions ‘a lack of monitoring’ and a ‘large risk’ of ‘siphoning off’ of the money; not really surprising in a country where diverting aid, like in a recent investigation into school food programmes3 is pretty much the entire governance system.

In Mozambique, both the provincial government of Cabo Delgado and the Ministry of Health refused to tell us where we might find, and interview, people who were assisted with specific COVID 19 relief cash. Another email with the same request to the ‘Social Action’ INAS institution in charge of cash transfers in that country bounced. Neither INAS nor the Ministry of Gender, Women, and Children, formally also involved in cash transfers to needy families, provide any further contact details on their website.

The district authority took issue with the prioritisation of recipients

A cursory look at reports on emergency cash transfers by NGOs in cooperation with Mozambique’s INAS and the disaster relief institute INGD shows that not only do this country’s state institutions not help much to deliver the cash to the needy; they often even stand in the way. A report4 by the World Food Programme on cash help for flood and cyclone victims in Mozambique notes that INAS ‘was not able to register all beneficiaries (…) due to insufficient funding via the project’, which means that INAS could not do what was supposedly its core job as long as it did not get more money for itself. The report also says that local authorities had to be ‘rallied’ through ‘important support by the local WFP office’ to perform their functions in the face of disaster. In one area the district authority ‘took issue with the prioritisation of recipients, which resulted in some delays.’

Erosion of skill and performance

South Africa is a different story. Whereas most African countries’ lack of capacity is historically connected to the fact that their state systems were established by colonialists, South Africa had a functional public service, which was in the apartheid past largely reserved for the white minority. Sadly, after liberation, the challenge to extend this capacity to serve all the people was not met; the ruling party instead used the state as a jobs programme for its members, who often lacked the necessary skills and experience to govern. The erosion of skill and performance was still exacerbated by the outflow of ‘apartheid’ civil servants, who had been the only ones acquainted with the management of operations. Nine years of fully fledged plunder under previous president Jacob Zuma, who actively encouraged further dysfunctionality and incompetence and presided over the weakening of key state institutions such as law enforcement agencies5, then led to a situation where, according to the recent comment quoted in the below article by governance expert Loren Landau, ‘there is little associated with South African service delivery that is not rife with corruption’.

Erstwhile ideals

Nevertheless, there are still state services in South Africa that do work, often thanks to individual civil servants who continue to adhere to the erstwhile social justice ideals of the former liberation movement, the African National Congress. The head of the SASSA social welfare agency, Busisiwe ‘Totsie’ Memela6, with her background as a courier in the armed resistance against apartheid, is an example of such an ethical veteran. But, like many of her colleagues, Memela now finds herself surrounded by a broken state, heading an eroded welfare institution that has been infiltrated by the corrupt.

The below is a look at the anatomy of a state agency that tries to help the starving in South Africa during a pandemic. It hopefully offers some insight into how even urgently desired help to the poor becomes an unsurmountable problem amid dysfunctionality – and also how corruption is more than a problem caused by corrupt individuals.

1. See: Coverage of non-receipt of cash transfer (Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty) and associated factors among older persons in the Mampong Municipality, Ghana – a quantitative analysis.

2. See: Etude sur les Modalities Operationnelles des Transferts Monetaires (2017–19).

3. See the chapter on Mali here.

4. See: Cash transfers and vouchers in response to drought in Mozambique.

5. See for example this article on Jacob Zuma as the ‘poster boy’ for black kleptocracy.

6. Totsie Memela is a long-standing acquaintance of the Dutch anti apartheid movement in which ZAM has roots.