72 hours non-stop shifts, no breaks, no equipment, no salaries. The Nigerian government fails to provide proper services. The country’s doctors seek jobs abroad.

One night -he doesn’t remember the exact date- in June 2017 at the Lagos University Teaching hospital in Nigeria’s capital city, three of eight pre-term babies died in the ward where Mohamed Gafar, 26, was the ward doctor.

He, an intern still waiting for his permanent license, was the only doctor on duty that night and was just reaching the end of his 72-hour non-stop shift. There had been thirty babies in the ward, eight of them pre-term. The three pre-term ones who passed, died because of the lack of oxygen supply, a problem that consistently plagued the government-owned teaching hospital where he worked. That day, nurses had sent word to the oxygen department to supply oxygen but it had never come. The oxygen department had merely responded that getting to that area of the hospital was cumbersome as the elevator was out of order.

In a way it was understandable. There had been only two people working in that department that night and one of them had gotten injured lifting oxygen tanks.

Gafar faced hundreds of similar problems while trying to practice as a doctor in Nigeria. “Sometimes, we lost patients because there were problems with lab results. Sometimes, there were no pharmacy supplies, other times, there was no blood from the blood banks,” he explains. Once, a 17 year old boy died just before he could get a brain CT scan because there was no under-trolley oxygen and also the CT scan machine was defective.

Doctors make contributions towards the medical bills of their patients.

Yet another problem is the system that demands that people pay out of pocket for costly procedures. According to another source at the same hospital, doctors, and even medical students, frequently make contributions towards the medical bills of their patients, but it is never enough. As Mohamed Gafar says: “Many patients die slowly on the wards as they're unable to procure what is necessary for them to get treated.”

These days, outside of the clinic where Gafar is participating in another compulsory one year youth service to Nigeria, he is either writing for his blog or reading medical textbooks to freshen his memory as he intends to write the PLAB (Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board) exams in 2019. Gafar wants to leave Nigeria for a residency program in surgery in the UK.

Like Gafar, Dr Kim Oyanuga (28) tried really hard to be a doctor in Nigeria. After navigating university in Benin State -where she had to avoid sexual advances from lecturers- she travelled throughout the country for ten months looking for a placement. In some places, candidates were separated according to their state of origin. (Nigeria is divided across tribal communities, which means that in certain areas there are preferential appointments according to tribal background.) In other places, candidates were told, illegally, to come forward only if they had a letter of recommendation from a top politician in Nigeria. When Oyanuga finally found a place at a hospital, a patient who needed ventilatory support died shortly afterwards because the ICU was without power for about 45 minutes.

Finally, when in 2017 Kim Oyanuga herself needed emergency surgery but was faced with long waiting lists, she found it in the UK. And, impressed with the care she received -she was in theatre four hours after diagnosis was made whilst in Nigeria she would probably have died on the waiting list and also did not pay a dime for a procedure that in her own country costs close to 1 million Naira ($ 2500)- that is where she stayed. She wrote the PLAB 2 exam in December and started in London in April 2018.

Gafar and Oyanuga are just two of the many Nigerian doctors who write exams to leave the country to practice their medicine in the United Kingdom, or elsewhere, simply because the conditions in their own country’s hospitals are untenable.

Even in generally better resourced private hospitals doctors are leaving, simply because ‘better resourced’ often still doesn’t amount to ‘good’. One may earn slightly more than the usual 400 Naira (US$ 1) per hour, though this is not always the case, but careers are hampered because of a lack of residence programmes while the nightmare of insufficient working equipment and opportunities to treat people reigns there, too. Like government hospitals, private hospitals also often can’t afford the necessary machines, and patients run out of money here as much as in the government centres. Many private hospitals do not even accept patients tagged as terminally ill.

One tries one's best, the interviewed doctors say, but at some point it becomes too much. In 2017, the Nigerian Medical Association announced that of the 75000 doctors registered in Nigeria a hefty 40,000 doctors already practiced outside the country. In the United Kingdom, about 12 doctors from Nigeria are registered every week. And as Nigeria’s economic fortunes have dwindled quickly in the past few years, it has been getting much worse. In March 2018 1,500 doctors wrote the Plab 1 exam to work in the United Kingdom and about 1,000 of them passed.

The exodus burdens the remaining doctors even further. In the National Hospital in Abuja where Dr. Ada Ohioleh works, she is frequently on call for three days straight handling several wards with over 50 patients each and having to manually pull information for every patient as there is no digital database. “I’m doing the work of three doctors. I can’t take any breaks because I’m the only person here and I frequently have to work as a secretary because there’s nobody else to do it,” she says. She, too, intends to move: in her case to the United States of America.

Nigeria only made a 3.9% contribution to its health sector in 2018

Nigeria’s healthcare problems range from simple budgetary constraints to a great deal of mismanagement and bad governance. Despite the recommended allocation of 15% of the national budget on health, Nigeria only made a 3.9% contribution to its health sector in 2018, translating to [US$4.6] on the health of each citizen in the year. This lack of allocation of funds to the health sector has made several states unable to hire doctors and medical staff in the country. In other states, doctors are owed salaries, which leads to strikes that often last for months.

On the supply side, state mismanagement also accounts for a lack of electricity, which has resulted in some instances in doctors performing surgeries using candles, lamps and lights from their mobile phones. Following the recent re-emergence of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there are fears that even Nigeria will increasingly be unable to deal effectively with such disease outbreaks.

“The doctors are moving to countries where the basics to practice their medicine are available,” Dr Niyi Abikoye, the owner of private Shammah hospital in Lagos explains. “Beyond opportunities to learn and practice with world class equipment, you want to practice in countries that provide the barest minimums in social amenities and security.”

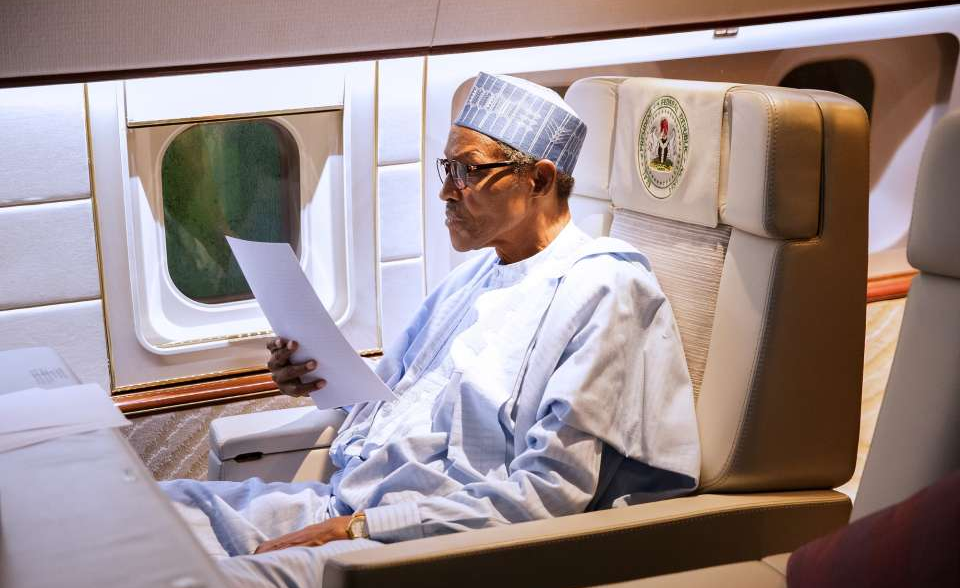

President Buhari took as many as five trips to Britain to get medical help

Ironically, better management of the health sector might actually result in more financial budgetary space, since many Nigerians who can afford to pay for their health care now opt to travel abroad for treatment. Among them is President Buhari himself, who recently took as many as five trips to Britain to get medical help for his undisclosed illness[es].

Nigerian Minister of State for Health, Dr. Osagie Ehanire, has said that Nigeria loses about $1 billion yearly to medical tourism: money that otherwise would have been paid to hospitals in Nigeria. Better management of state structures could also see the much-announced but hardly implemented National Health System, which would extend basic public health care to all Nigerian citizens, become a reality. But with the bad governance that plagues Nigeria, this, too, remains a pipe dream for the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, Nigerians who can’t afford to travel abroad to get treated, or even afford to pay for procedures in their own country, increasingly rely on quacks: unqualified individuals who call themselves ‘doctors’ on leaflets and in adverts. Simultaneously, a huge illegal drug market -flooded with fake and expired, but available and often more affordable medicines- is booming in Nigeria. With terrible consequences: The WHO reported in 2017 that over 116,000 deaths per year in sub-Sarahan Africa are linked to counterfeit or substandard antimalarial drugs alone.

For Mohamed Gafar, on his way to the UK, it’s just a matter of time until these problems are no longer his problem. Kim Oyanuga feels better than ever. “My health is probably the best it has ever been. My allergies have reduced to the barest minimum and I have not had an asthma attack in six months,” she laughs. But that doesn’t mean she has stopped thinking about Nigeria. “The loneliness is out of this world. Sometimes, it feels like I'll die from how homesick I am.” Gafar, too, wouldn’t mind coming back to Nigeria one day. He and Oyanuga plan to one day become consultants and help fix Nigeria’s systemic problems. But first they intend to settle into other countries where their skills and talents can be maximised.

Oluwatosin Adeshokan is a journalist and documentary producer currently living in Lagos. He reports about the West African bloc on development, finance and conflict. He has been published by OZY, Popula, PRI and TRT World. Follow him on Twitter @theoluwatosin and Instagram @oluwatosinadeshokan