DR Congo | The ‘Virunga’ movie shows the rangers of the gorilla reserve in the DRC as heroes. The real picture is far more complex.

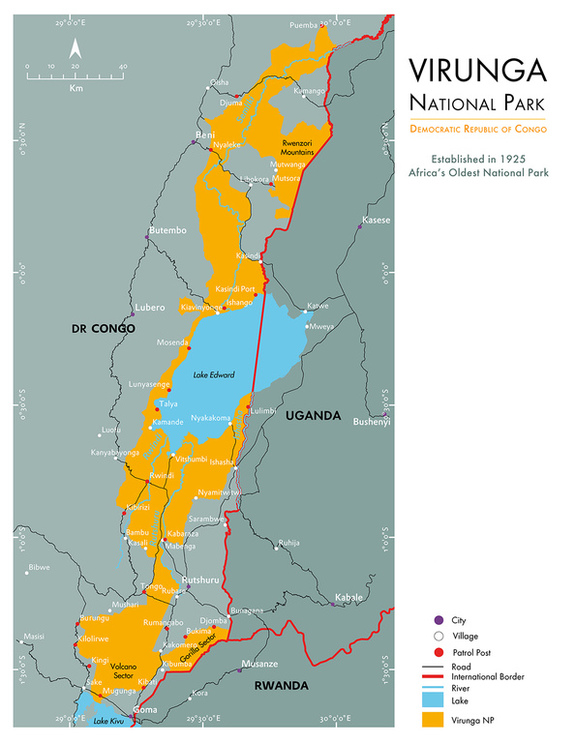

The new Virunga movie, showing at the international documentary festival IDFA, portrays the heavily armed rangers of the gorilla reserve in the DR Congo as heroes. They protect the pristine hills of ‘Gorillas in the Mist’-fame, the two hundred actual rare mountain gorillas and herds of antelope that live there, from plunderers, rebels and greedy oil company executives threatening to turn the place into a Niger-Delta-type hellhole. In the movie, the Park Rangers are adored by all the parks’ inhabitants: whether animal or human, all are grateful for the selflessly provided protection of their beautiful environment. In reality, the environmentalist Belgian commando-trained army is just one of the problems local people face when trying to make ends meet.

“We haven’t had meat in years”, says former hunter John Ilunga, 60, of Nyakokoma village. “Even the black market has dried up.” Besides fish, game meat is often the only protein people in Virunga get to eat. Ilunga looks wistfully when he recalls the days when ‘there used to be warthog and buck and more meat than you could ever want. But that is forbidden now.” His colleague, Ndayambajé, 42, who also used to hunt, now sells potable water to villagers in Kiwanja. But carrying water tanks on his bike all day is a ‘lousy job’, he says, compared to the good old days when he was free to hunt hippos and other game in the park. “We were selling leather, bones, meat, you name it”, he says. “It was a good life. But these days are over now that the park is no longer ours.”

Their father’s and grandfather’s professions are illegal now.

The former hunters are called ‘poachers’ now; their fathers’ and grandfathers’ professions are illegal in these modern environmentalist times. They can only hope for employment in conservation or tourism, as per Parks boss William de Merode’s plan. De Merode, a Belgian royal and an uncompromising environmentalist, has outlined a blueprint for a peaceful, eco-friendly, conservation-and-tourism-based economic system in the park that must provide for all 27, 000 families who eke out a living of fishing and farming in the area.But that, if it is to happen at all, is way in the future. For now, the Park Rangers simply limit the spaces where you can farm or even walk. They are everywhere with their AK-47’s, RPG-launchers and other heavy armament, dotting the horizon in their uniforms and rubber boots. “We protect animals, that is all. You can’t ask me any questions. I won’t talk to you”, says one we encounter, sternly.

Buffalo, firewood and electric fences

A couple of months ago a woman was stamped to death by a buffalo as she was searching for wood a few hours’ walk away from Nyakakoma. Fellow villager Kahambu Sifa, 35, is scared now, but still needs to go nevertheless. “They tolerate us, but looking for firewood it is not a right, so we don’t get protection.” Elephants trample farm lands and villages, too, whilst monkeys pillage kitchens and other places of food storage. Villagers chasing them keep getting told not to harm the animals.

In some places, the nature conservation parastatal ICCN (the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation) has erected electric fences to separate farm lands and villages from nature areas, but the conflict continues: the park accuses villagers of invasion, whilst villagers accuse the park management of stealing their lands. The ‘sustainability’ workshops held by the ICCN have not yet convinced the population. “It seems farming here is forbidden now”, says Rutshuru farmer Ngambo Kizito. “I cannot burn my land anymore to prepare it for new crops. Nowadays, I must call the specialists before I can even cut down one tree.”

But the environmentalists are not wrong. The area’s resources are really getting depleted: “Nowadays I catch ten fish in a day, whilst twenty years ago I’d get a thousand in one go”, says Lake Edward fisherman Baseme, 40.

The rebel army M23 also takes tourists to see gorillas

Causes of the depletion vary: there is general over-fishing prompted by lack of meat; there is pollution from unregulated tourism; and there is the poaching of hippos, whose teeth are valuable in a way similar to rhino horn. Since hippo’s excrement provides fish food, less hippo means less fish. Major over-fishing, poaching and culprits are the militias, remnants from the Congo war, who roam and plunder here. Some of these, notably M23, have even taken tourists to see gorillas for a fraction of the official park price.

Enter the government, not to fight the militias, or to provide new ways of living and employment to the area, or to provide guidance and leadership and regulation, but to make things, -at least in the eyes of many-, even worse. In 2011, it sold an exploration license to British company Soco after oil was discovered under Lake Edward. Two years later it would pocket close to US$ two million from Unesco to protect the park as a world heritage site -thereby cashing in twice on a sale to two diametrically opposed parties. When Unesco and the environmental organisations found out that oil exploration was still going on, all hell broke loose.

Big Oil comes with bribes and T-shirts

It was then, as can be seen in the Virunga movie, that Parks boss De Merode rallied his troops against the oil invaders. His protest was joined by scores of environmental NGO’s that pointed at a Lake Edward fishing site being fenced off now not by park Rangers, but by Soco. This also upset Nyakokoma fisherman Paluku Kasereka, 33: “Soco kept us away for some time from a spot we use to go out with our boats. Wouldn’t it be better if fishing was protected, rather than oil? At least we benefit from the fish, whereas the oil is for the whites, who want it so desperately.”

We benefit from fish, oil is for whites

NGO’s also denounced bribery attempts in the form of T-shirts and solar panels by Soco officials directed at local chiefs, as well as payments made by Soco to military kingpins, including rebels, in te area. (Soco denied that bribery was its policy and promised an investigation.) When De Merode was shot in an attack on his convoy on 15 April this year, environmentalists were quick to blame Soco’s security, though it later transpired that it was probably a poaching-related militia attack. However, secretly recorded footage in the Virunga documentary does show callous disregard from Soco officials with regard to locals. One calls them ‘children who cannot take care of themselves’; the other dismisses them as ‘savages.’

The fear that the park might be ruined by ‘big oil’ is perhaps not so much directed at oil exploration itself: after all, oil exploration in well-regulated places like Norway has not significantly damaged the environment. But in the DRC the government has always sold out the riches of the soil to the highest bidder without any regard for the well-being of people or environment in the affected areas.

The right to exploit

There are some who don’t seem overly concerned about this history. Albert Kabasele, head of the Agriculture Faculty of the University of Kinshasa, for example, supports the oil exploration endeavour because ‘the country has to be free to exploit its resources’. And Flory Nyamwoga, secretary of the DRC’s National Land Reform Commission, believes that “an oil project can be handled sustainably, in the interest of the surrounding communities, like in the Queen Elizabeth National Park in Uganda.” But many locals are all too well aware that the country’s richest province, Katanga, is now radioactive in places and full of dead mine workers’ bodies, because of rapacious and unsafe uranium mining.

Remarkably however, the very same mistrust in the government has caused some in Virunga to direct their expectations to oil company Soco itself. “We can jump high or low, but our government will do as Soco pleases anyway. Let’s hope they give us jobs”, says Jean Kambale, a young fisherman of 19 in Nyakakoma.

"We can only hope to get some jobs"

Kambale has attended the briefing Soco has given to the villagers, where a great deal was made of new roads, solar panels and other improvements the company has started to construct in the area. Kambale hopes for the best, but for now he has only seen Ugandans, and not Congolese, being given employment. “They seem to think that Ugandans are better qualified.” His fellow villager Kahambu Sifa agrees: “Even for kitchen jobs they are bringing Ugandans”, she says, adding that she knows this from a –Ugandan- friend who works for Soco in catering.

Another young inhabitant of Nyakakoma, Jérémie Kandolo, who makes a living from his small farm for himself and his little brother of twelve, says he has seen ‘much suffering’ at the hands of the militias. ‘Mai Mai, the one of Laurent Nkunda, M23, CNDP, and our own army as well. They have all hurt us. But since Soco is here, there is security. I just want peace.”

Notes: Eric Mwamba led a team investigation on the ground in Kinshasa and Virunga. The team consisted of Francis Mbala (Kinshasa), Clarisse Muamba (Kinshasa), Dieudonne Mulela (Virunga) and Elvis Katsana (Virunga).

The World Wildlife Fund deposited a formal complaint against the DRC and Soco at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD, in Paris last year. Soco has responded to the complaint by saying it is withdrawing until the issue is sorted out, but many local reports concur that exploration by Soco continues. The DRC government and its supporters say that the complaint is disingenuous.