Read the full article in Dutch here.

The Force against Zuma’s empire

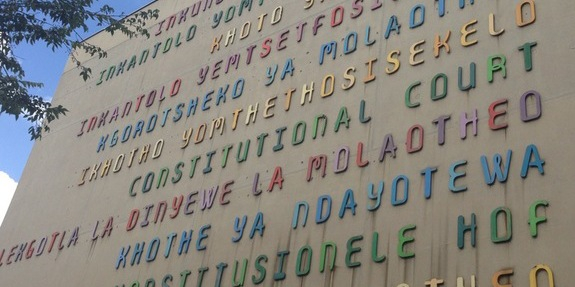

The increasingly loud and growing rebellion against Jacob Zuma's empire in South Africa is supported by a very powerful weapon: the Constitution of the country, once designed, after the demise of apartheid, under the supervision of Nelson Mandela. It is this Constitution that simply won’t allow Zuma and his government to get away with corruption and authoritarianism. In the war that, a la Star Wars, is now fought between a bad ruling elite and a wide alliance of rebels, the Constitution plays the role of the mythical Force. It has already helped turn underground discontent into an incipient revolt.

South Africa’s Gold Reef City fun fair, a kind of mini-Disneyland built on an empty old gold mine and themed around the 19th century gold rush, -with wagons full of visitors participating in a quest for gold with no gold anywhere in sight-, is a metaphor for plunder. Gold was always only a fairy-tale to most South Africans after all. (Unless you happened to work in the mines, in which case it was a nightmare.) It is therefore perhaps fitting that it is in a restaurant here, on an afternoon in January, amid fake gold and dizzying upside-down mountain rides, that a group of democracy activists meet to plan rebellion against the Plunder King: the increasingly powerful, increasingly dangerous, Jacob Zuma.

I am not wanted. “Comrades, we must defend the Constitution,” is all I hear before I am shooed away. Understandably so. The rebel alliance consists of individuals who have had phones tapped, laptops hacked, houses broken into. They whisper, with phones off and in coded language, saying they can’t risk letting in a journalist. They want to avoid further alerting the spies working for the President, -who, I realise, as I find myself outside and alone in the sandy, noisy city of fake gold, looks a lot like that warlord from the Star Wars movies, the massive, gluttonous, leathery, evil-eyed and giggly Jabba the Hut. Just like Gold Reef City, with its noisy taverns, strange vehicles and sand, looks a lot like Jabba’s pirate planet.

Apartheid Museum

The Apartheid Museum is also here. Smiling theme park officials who don’t distinguish between this place and the Anaconda ride next door tell me to ‘have fun’ as I enter the place that houses the gallows that hung Solomon Mahlangu on my way to a lecture about South African democracy. South Africa is also always just an inch away of being a full-on Fellini movie, too.

In the Apartheid Museum, two Constitutional elders, former judges and authors of the South African Constitution, -Knights of the Round Table who guard this democracy-, are set to speak. The Constitution, a document the size of a small booklet, prescribes non-racialism, non-sexism, democracy, social justice. It protects against full authoritarian rule, the kind that the Plunder King would really like to have. (He has said so twice and publicly by now, in statements that have made the opposition even more determined never to allow this.) The Constitution etches in stone all that the anti-apartheid struggle was fought for. Like the comrades in the restaurant next door, the two are here to explain to us why it must, now, be defended by all.

Justices Albie Sachs and Dikgang Moseneke address an audience of several hundred concerned inhabitants of this country about the how and why of the creation of a new rule of law for the country after apartheid was defeated. “The Constitution is about right and wrong, not about dry words and difficult texts. You can’t have a constitutional text without values. You need to reflect what is good and right,” says Albie Sachs. “You need heart as much as brain.”

It was the Constitutional principle of equality of all that served, last year, to dish out a blow to the President after he had taken tax payers money to fortify his palatial complex at Nkandla. He had to pay back the money, the Constitutional court had said. “It’s a simple principle, but it works,” says Dikgang Moseneke. “The commander in chief simply cannot have all the countries’ goods.”

“Just having a revolution doesn’t mean that we are all suddenly beautiful people.”

Albie Sachs goes on to explain that, in drawing up the Constitution, in 1996, together with all political forces in the country, the new legal framework was designed to ward off dangers that other liberated, newly independent, countries had faced. Think plunder planet Mozambique, think Supreme-Ruler-Zimbabwe. “We had to acknowledge that brave fighters can become authoritarian rulers,” says Sachs. “Just having a revolution clearly didn’t mean that we all suddenly become beautiful people.”

Moseneke pulls no punches about what is going on here, now: “Majority rule should never be used for abusive purposes. When I see patronage” -the dishing out of positions and favours to political allies, EG- “and failure to observe basic tenets of good governance, I get very worried.” Sachs admits that, back then: “some of us thought we would not need to write down individual human rights and rights for minority groups. The ANC would be the majority and the ANC would be good, we thought. But Oliver Tambo, the then ANC President, was the one who insisted that there should be a Bill of Rights. Boy, am I now happy he did that.” Both emphasize that the Constitution is a weapon in the fight for good governance. Moseneke: “It helps us to stay with the journey towards the society we dreamt then.”

The King and his fiefdom

It is a hard battle though. All of us here at the Apartheid Museum are painfully aware how the Warlord President, with 783 counts of corruption hanging over his head, but escaping the courts through incessant appointments and reappointments of loyalists at the National Prosecuting Authority, has beheaded the justice system into paralysis. After also appointing vassals in the police and security forces, political opponents now have been facing charge after charge while real criminals were left to do as they pleased. Loyalty -now also often called ‘unity of the ANC’ supersedes every other consideration. “Zuma sees himself as a King: the state is his fiefdom; its resources his patronage & the constitution an impediment to his personal beliefs,” journalist Gareth van Onselen summarised, in a tweet last year, the Presidents’ seemingly permanent frame of mind.

“Zuma sees himself as a King”

The Nkandla judgement by the Constitutional Court last year had given a clear sign that South Africa’s highest court of law was ready to continue the fight for the society that had been dreamt by its founders. The ‘pay back the money’ verdict inspired South Africans, who were glued to their TV screens when Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, dryly and with a twinkly smile, spoke his hard-hitting words about the President breaking his oath of office and violating the Constitution.

After that, Mogoeng Mogoeng and his Constitutional Round Table had continued to intervene on behalf of the values they were tasked to defend. After Nkandla, they had stopped Zuma’s henchman police minister Nathi Nhleko from victimising police complaints investigator Robert McBride, who is now back in his job fighting police abuse. The ‘Concourt’ had also sided with Lawyers for Human Rights when they protested the abuse of illegal foreigners in detention. It had recently come out, guns blazing, to defend the children, the old and the sick when they declared social welfare minister Bathabile Dlamini, another Zuma-favourite, ‘totally incompetent’ for her corrupt deal with the shady business she insisted had to distribute South Africa’s welfare money.

Rights and attacks

The Constitution made democracy activists feel strong. “They said they’ll sue me for defamation, but I can petition parliament, it’s in the Bill of Rights,” Adrian Lackay, the former tax spokesman, who had written to parliament to denounce the damage at SARS done by Zuma loyalists, had told me, smiling. It had been no easy ride for him: he still suffered slander and attacks. But the fact that there is that Constitution that says you are right to do the right thing, helps.

The lower courts, operating in the same constitutional framework, had also played their role. The Labour Court had protected the two top executives at the tax authority, one of whom was my husband, from being booted out for no reason. The Court could not get them reinstated, but it gave them a leg to stand on in negotiations with the boss, and a verdict that said they had done nothing wrong. The High Court had also helped to throw sand in the machine of Zuma’s pet supreme policeman Berning Ntlemeza, who was always persecuting honest officials on flimsy charges. Their judgement that Ntlemeza was ‘dishonest’ and ‘unfit’ for his job would finally see him dethroned in April.

The courts cannot do everything. The Zuma president is still in power. But at least the fear of the Constitution is real in the ranks of the corrupt. Which gives rise to another danger: that Zuma will attack it. “I think at some point he will try to suspend the Constitution,” one of the fired tax officials confides one afternoon, in a whisper. Fortunately, we agree, that won’t be easy. The President would need a two-thirds majority in parliament. But he might try.

He has support from plenty henchmen already. Chief propagandist Mzwanele Manyi, the chairman of the Black Professionals Forum, the Decolonisation Foundation and an array of other institutions who are very vocally pro-Zuma on Twitter and other social media (and who just will not disclose who funds them,) has already repeatedly called the Constitution ‘modern apartheid.’ He supports this label with the argument that, by protecting rights of individuals and minorities, the Constitution ‘disadvantages the majority.’ (This majority being, of course, the ruling party under Zuma.) Joining the fray recently, Zuma’s anointed successor and ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma -by all accounts ready to take over his Empire- has said, chillingly, that the legal system must be ‘strengthened’ because the ‘opposition’ was now ‘governing through the courts.’ The statement left opponents puzzled with regard to the meaning of the word ‘strengthen.’

Intimidating tweets

The first week of April, after the firing of the finance and deputy finance ministers Pravin Gordhan and Mncebisi Jonas, saw the first signs of such ‘strengthening.’ When massive protests against the country’s slide into economic junk status were being called the government twitter account sent out a series of intimidating tweets against ‘civil disobedience.’ On the night of 5 April, protestors camping at Church Square in Pretoria were confronted by belligerent ANC Youth League members who took their tent and some other goods. A week later, a few busloads full of similarly fired up Youth League troopers disturbed an Ahmed Kathrada memorial in Durban where former minister Gordhan spoke. Council meetings in cities where the opposition now holds a majority have been the scene of chair-throwing and physical fights caused by ANC politicians who can’t accept electoral defeat.

Other illegal acts by those who hold state power are increasing too. After the Constitutional Court judgement had placed strict limits on Social Welfare Minister Dlamini’s contract with her shady money distributor friends, the offices of the Court were broken into and computers full of personal details of judges and court personnel were stolen. (The criminals had gone straight for the judges’ data, overlooking the computers in the IT, finance, training and communications departments on the ground floor in the same building.) Months before, armed robbers had done the same at the opposition-linked Helen Suzman foundation. They had left other business in the same building and other valuable items alone, again going straight for the Foundation’s computers and taking them.

In the same period, honest state officials who had had to resign or were fired from their jobs, -among them former tax- and policemen and even a social welfare department official- also experienced burglaries and break-ins. In some cases computers had been stolen, there, too. Once -in the case of the social welfare official- his children had been intimidated by men with guns. Justice Mogoeng himself had been hijacked, had had a gun put to his head in front of his house.

Was this ‘strengthening of the legal system,’ Zuma-style? Or ordinary crime? A mix of the two? It was remarkable though, that these things never seemed to happen to Zuma loyalists.

Kathrada’s generation

Meanwhile, protest is growing. The Constitution and its values feature in numerous placards and speeches at the at least 100 000 strong protests at the Union Buildings on 7 and 12 April. “We must defend South Africa’s vision and Constitution,” is fired minister Derek Hanekom’s call to arms at the funeral of Nelson Mandela struggle buddy Ahmed Kathrada, a member of that same old ANC generation that inspired it. Pravin Gordhan, speaking at the Kathrada memorial event in Durban -just before the ANC Youth League would drown the event in pro-Zuma songs-, also calls for these principles, that “were in the DNA of Kathrada’s generation,” to be fought for and revived.

“Values that were in the DNA of Kathrada's generation”

A walk through the Apartheid Museum illustrates how this DNA was indeed there, at the beginnings of the struggle, grown out of the deeply felt injustice of apartheid and imbibed by the men and women who would spend their lives fighting for what was right and just. Mandela’s own father, I read as I pass an exhibit on my way to the Constitutional lecture, was sidelined as a chief and fired and exiled from his region for refusing to comply with an unjust ruling of white masters. Grown up without his father, Mandela junior would later also oppose traditional African authoritarian rule by escaping an arranged marriage and seeking freedom in urban Johannesburg.

Later, in court, expecting the death sentence, the same Mandela had uttered the now legendary words “I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” It is this ideal that Jacob Zuma’s increasingly authoritarian rule of a privileged few is violating at every turn.

Fortunately, Mogoeng is still here, surrounded by his Round Table, not smiling when he addresses a press conference after the break-in at his offices. “We’ll do whatever it takes to defend constitutional democracy,” he says. “There’ll be consequences to flaunting court orders.” But will he and the other judges be strong enough? Will the rebel alliance win the fight? As we, terrified, hold on to our seats on this roller coaster ride high above the pirate planet’s city of gold, we can only hope that the Force will be with us.