Don't just do something. Stand there.

The list of calls to ‘do something about it’ is endless. They are heard from Washington to Worcester and from Paris to Perth. To catch and arrest a warlord in the Congo, to improve working conditions for workers in the textile industry in Bangladesh, or to stop violence altogether in Darfur. It’s about trafficking and forced prostitution, child labour and oil pollution, anti-gay laws, abducted girls, endangered Bushmen and rhinos. One campaign after the other.

When activist citizens from across the world get up and ‘do something’ is not always positive

Sometimes a digital signature suffices; every now and then emotionally committed ‘citizens of the world’ leave their privileged spots to go and do ‘something about it’ right there. Usually unhindered by a lot of knowledge or understanding of complex issues, they will go in and apply a quick fix because, well, they are just very committed. Only to end up, more often than not, feeling a bit disappointed or embittered. Or even racist. Because ‘they’ did not, and will never, understand. Because good intentions were not appreciated, good plans not helped along, or even sabotaged.

Kidnap confusion

Maybe they were robbed, or beaten up, or kidnapped. If that happens, they suddenly find themselves at the centre of attention, instead of the evil they went to fight. Dutch self-proclaimed Maasai farmer, Jandries Groenendijk, tried to fight the confusion he must have experienced when he was kidnapped in the Niger Delta by the very unemployed youngsters he came to help, by reverting back to a delightfully clear and simple scheme of right and wrong. In the end it was all Shell Oil’s fault, he explained in a talk show on Dutch television after his release. (For what actually happened, see elsewhere in this issue of ZAM Chronicle.)

The temptation to dismiss these modern forms of engagement with a pen dipped in hardcore cynicism is great. But even without cynicism, we can, I hope, arrive at an understanding of the fact that this kind of activism often does more harm than good. A South African friend, a born activist, recently told me that ‘it is sometimes better to not just do something, but to stand there.’ This startled me, because I, like many of us, grew up with the exact opposite admonishment: ‘Don’t just stand there, do something!’

Clicking on a petition may be of less consequence than boycotting products from a poor country, but both can be harmful

‘Doing something’ can manifest itself in different ways, of course. One can go and face the ‘enemy’ directly, like Jandries Groenendijk did. But ‘doing something’, or at least the wish to be doing something, is also the driver of consumption and boycott campaigns, as in refusing to eat or buy certain products, or only consuming food that comes with a ‘correctness’ label. Recent research by a team from the University of London confirmed, in this respect, what African investigative journalists already knew: that ‘Fair Trade’ doesn’t help poor farm workers at all. “But what should we then do instead?” was the response from some of my friends, who had apparently been living with the misapprehension that their consumption habits meant that they were actively doing something.

Clicktivism

This misapprehension is also behind the phenomenon of the internet petitions that widely circulate from laptop to laptop nowadays. On this issue we should note the words of professor Tavia Nyong'o, a Kenyan American historian and cultural critic affiliated with the University of New York, that such ‘clicktivism’ “creates a fantasy of participation, an illusion we can have that we are ‘doing’ something, or participating directly in a crisis that may have complicated local implications. This may give us some immediate emotional satisfaction but may do little to address problems on the ground and may, in fact, make things worse for those who lives are affected.”

Merely clicking on an internet petition may be more harmless than boycotting products from a poor country full of people trying to export their stuff, who are being banned from selling because their children help out on their farms. And that may still be more harmless than actually going to the Niger Delta to support a warlord who poses as an oppressed revolutionary. But all these acts have one thing in common: in the absence of a thorough understanding of all the complexities, they could, as Nyong’o says, very well be harmful to some degree.

But doing nothing is against the nature of the activist. One ends up torn between such ‘doers’ and the fatalists, who never want to do anything at all. What to do when your disgust with harmful activistic megalomania clashes with your antipathy against petty bourgeois passivity, of the kind that mocks ‘forget it’, with every ‘Yes We Can’?

People have forever gotten themselves involved in conflict in distant countries. In the nineteen thirties, internationalists swam against the current to form ‘international brigades’ in the struggle against General Franco’s fascism in Spain. Former colonial powers were frustrated by the desertion of soldiers who crossed battle lines to join independence movements. Activists from the Netherlands, the UK, France and Canada actively participated in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Argentinian Che Guevara’s role in liberation movements all over South America and even Africa is much less a topic of discussion than the degree of success he achieved.

Warm feelings

I don’t want to scoff at such solidarity, and I still have warm feelings towards Western movements that supported, from a distance, liberation struggles in countries like Angola and Mozambique, protests against the dictatorships in Chile, El Salvador and Nicaragua, against the American occupation of Vietnam, the Suharto regime in Indonesia or Jaruzelski in Poland. Thinking back to all the protest marches I participated in makes me dizzy even now. Regret? Not really.

So why do I feel so uncomfortable with the forms of contemporary engagement described in the beginning of this piece? I suspect that this is due to lack of an actual movement. Nowhere in the current campaigns is there any presence of the people in the affected areas themselves, except as victims. No mention is made of what they do to address the social injustice in their own countries. Whilst the news on TV shows images of the indignant protests by Indian women and men against the rapes in that country, the presenter asks what ‘we’ can do about it. But shouldn’t the question be what the Indian women’s movements are doing, and how we could support them?

Western citizens are often unaware of the views and proposals of local activists who fight injustice in their own countries

There are farmworkers’ unions in the cocoa fields of West Africa, and textile workers’ protest movements in Bangladesh. They are not created by Western donors but by local activists. Ugandan nuns battle around the clock to reintegrate former child soldiers back into society. In the same country, gay rights groups take action against repressive laws. Nigerian investigative journalists leave no stone unturned to get to the bottom of the systems of human traffic. An understanding of how Muslim communities can reconcile the rights of women and sexual minorities with their religion is not growing in our faraway and ignorant heads, but in the minds of South African scholar Farid Esack or his compatriot, Cape Town imam Muhsien Hendricks and his organisation Inner Circle. And so on.

But many Western activists of today seem totally unaware of this. They show little or no interest in the possibility that the people they want to support could have agency of their own, or would have ideas regarding what, exactly, outsiders should contribute to their struggles. Some ‘committed’ internationalists achieve a semblance of authenticity by quoting local ‘NGOs’ , but such NGOs have often been established by Western donors in the first place: often to ‘raise awareness’ of local people to issues that they, according to the donors, should be concerned about.

Airbrushed away

The difference between what is called ‘commitment’ now and the solidarity of the past is that the movements of people themselves against the social injustice that affects them have been airbrushed away, only leaving ‘us’ in the ‘developed’ world with a focus on ourselves and our own rather overestimated power. Solidarity, anno 2014, has given way to selfiedarity. Contemporary international activism keeps the camera focused on itself and produces images in which it is at its own centre. It markets its own solutions and agendas, prescribes them to people far away and does not seem to be aware that these very people end up shaking their heads and shrugging their shoulders. An increasing tendency among African activists to keep a certain distance from their know-it-all supporters is the result.

When did this trend start? Is it an effect of globalization, a recognition perhaps that conflicts are often caused by complex international factors? Is that at the root of the misunderstanding that you can appropriate, without even as much as a dialogue, all agency against all evils, to yourself? Do multinational actors like Greenpeace and Amnesty International obscure – with the best of intentions, of course – the difference between the work of local activists and international campaigning? Do charitable organisations and their boastful PR encourage gross overconfidence among those who give? Is this all a question of a hunger for simplicity and a naïve hope that ‘good intentions’ can create a whole new world? Is it all given extra passion and glamour by the increasing involvement of Hollywood stars and their European counterparts, whose image and profitability benefit greatly from their support of a good cause?

There are very few ‘voiceless’ people; it is the listening that needs work

I am not saying that those who want to fight injustice in the world should blindly wait for instructions from ‘the people themselves’. Solidarity can only be built on equal partnerships. And obviously, local activists don’t all have identical opinions which they could communicate to us in one clear message, spoken with one clear voice. This is the mistake (or self-serving propaganda) put out by many NGOs and other self-appointed spokespeople, who call themselves ‘voice of the voiceless’. Here is a newsflash: there are very few voiceless people. Most people have voices, and they use them too, often loudly. It is the listening that needs work.

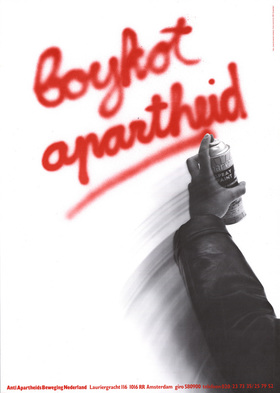

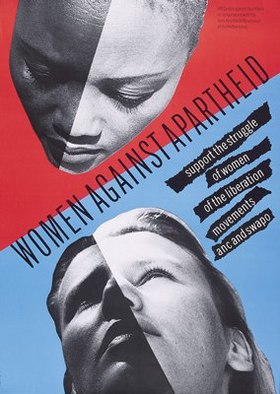

And then, hopefully, what ensues is a dialogue. That element was missing in quite a few of the ‘unconditional solidarity’ movements in the 1970s and 1980s. It led to the covering up, by some activists of those days, of painful excesses in the ranks of African, South American and Asian liberation and independence movements. In the late 1980s the Dutch Anti-Apartheid movement successfully added critical distance and an engagement with modern debates in the liberation movements – on issues such as feminism, gay rights and media freedom – to continued intense solidarity.

A new type of agency

Could we build on that experience and restart the quest for real solidarity? Let me make a boring suggestion: laboratories. Research centres. Perhaps listening, studying, doubting, weighing, probing, and asking can result in a new type of agency. Instead of feeling threatened by confusion and doubt, let’s cherish these. They are part of the search for truth. Let’s enter a place that fizzes and vibrates with new findings and expertise, where views clash, and where a foundation is laid for new explosions of solidarity. For satisfying (and sometimes maybe risky) liaisons with reliable, free and independent minds; for alliances with those who want to search for truths and confront powers. Real voices from farmers, unionists, women’s rights associations. Maybe doing this would not be so boring after all.

Dream on, you say?

Yes, we can.

Bart Luirink is editor in chief of ZAM

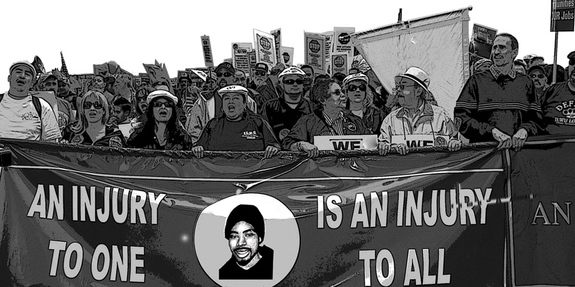

The images in this essay have been borrowed from ‘Signs of Solidarity’, a small exhibit on the Dutch solidarity with the struggle against apartheid. The exhibit, a ZAM project, was supported by the Dutch embassy in Pretoria and the South African embassy in the Netherlands. It was curated by Paul Faber and designed by Dave Hoop. ‘Signs of Solidarity’ will be on display both in South Africa and in the Netherlands, with the South African opening programmed for 3 July, during the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. On the 4th of July, Bart Luirink will hold a lecture on the subject of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement, titled ‘Future Memories’, at Rhodes University in Grahamstown.