Do Not Disturb, the latest of Michela Wrong’s Africa-themed books, is a penetrating examination of a gruesome murder committed in a posh hotel in post-Apartheid South Africa. This country was infamous for chasing African National Congress (ANC) officials and freedom fighters, whom it labelled communists and terrorists, wherever they hid. The boer regime had a special hit squad within its intelligence and security apparatuses that had all the names of the people blacklisted for death.

Akin to Murder Inc., a New York Mafia outfit that was notorious between the 1930–40s, the South African Boer regime sent hit men to wherever the ANC cadres were domiciled and to use Mafia parlance whacked them. As fate would have it, Karegeya was ensnared by a Rwandan hit squad in the night, at Michelangelo Hotel, room 905 Sandton and strangled to death. It was 20 years after South Africa’s transition into democracy.

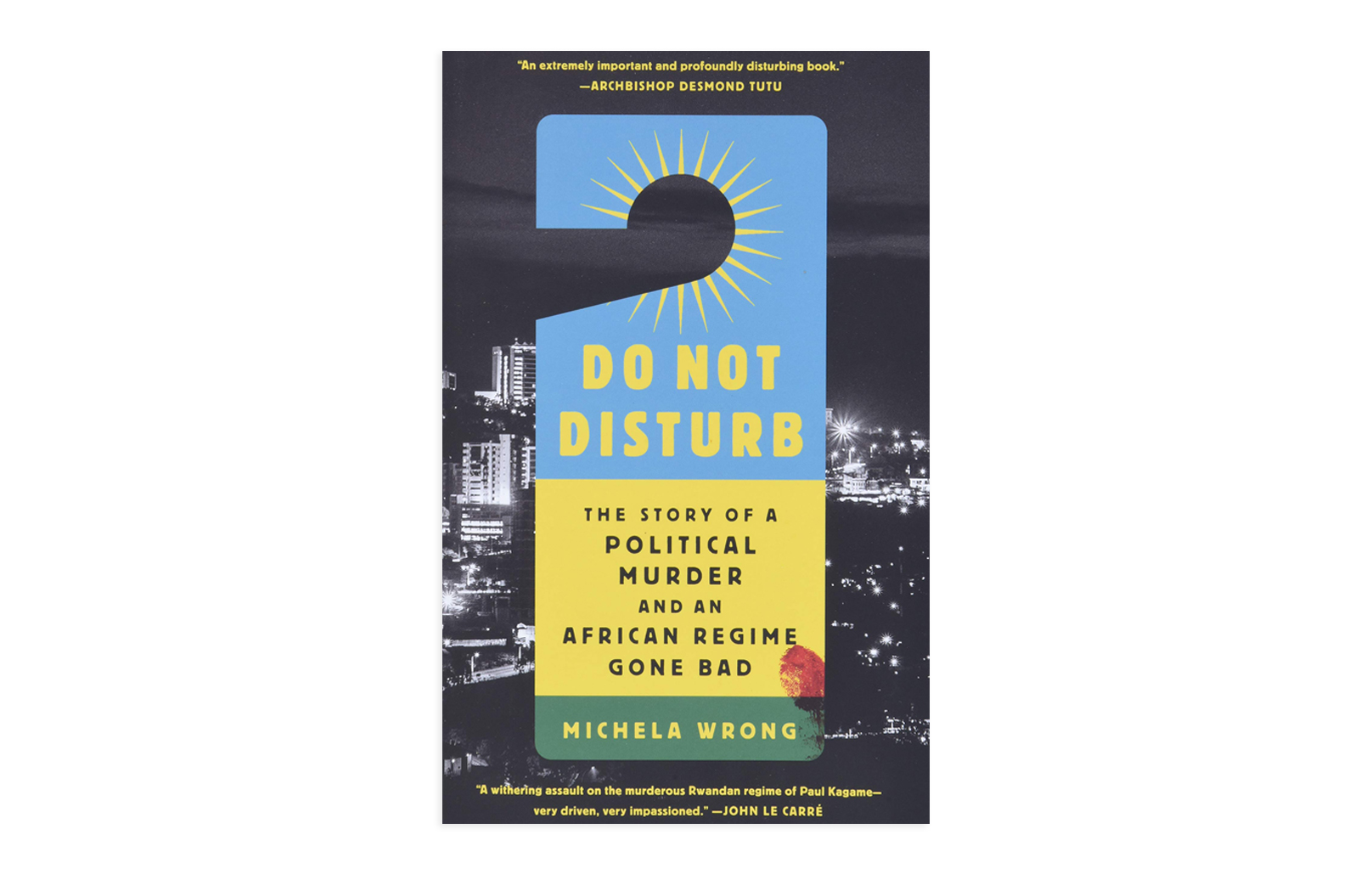

After the job was done, the assassins professionally hung the Do Not Disturb sign on the hotel door and then slipped out of the country. In April 2019, five years after the murder had taken place, an inquest that had been delayed for political reasons, was held in Johannesburg. It concluded that Patrick Karegeya had been killed. The South African Directorate of Prime Crime Investigations, Hawks, also concluded the ‘Karegeya job’ was ‘directly linked to the involvement of the Rwandan government’

What explained the grim determination with which Kagame suddenly set about the task of dealing with Karegeya? Michela in her book, offers a lead: ‘Patrick certainly knew where all the skeletons were buried. The years he spent working in both Ugandan and Rwanda’s intelligence services meant he was on top of the region’s every secret.’

Reading Do Not Disturb, one is thrown back into those dark days of that notorious Apartheid regime: which sometimes would leave obvious tell tales signs to warn, whomever, that we will also come for you just like we did to XYZ. In those days, the death squad was efficient and feared and had the blessing of the racist South African state rulers.

The book also talks about the attempted assassination of Karegeya’s former comrade-in-arms General Kayumba Nyamwasa, who also spectacularly fell out with Kagame, in South Africa. The timing of the attempt could not have been more critical. It came when the ANC government least needed such an incident, on June 12, 2010, the second day of the soccer World Cup fete.

‘When the General was shot, the official reaction was one of total shock and outrage’, former South Africa ambassador Thembi Majola remembers. ‘The response was: really? You want to come and do this rubbish here when the whole world is watching the World Cup?’, Do Not Disturb records.

Why is General Kayumba so feared by Kagame, his former boss? Do Not Disturb provides an answer: ‘The General clicks with ordinary soldiers, who instinctively trust him. He always has.’ The book further states: ‘However drippingly contemptuous Kagame may sound in public – and the state controlled Rwandan media’s obsession with the general’s activities is a give way – he fears no one as he fears General Kayumba.’

Summoned to appear before a ‘disciplinary committee’ comprising top military, police, intelligence officers and RPF party honchos, he was grilled on his presumed insubordination: ‘Since you left, some people in the armed forces here always remained loyal to you. The newspapers write positive things about you all the time and criticise government, while you never deny it.’

Through the unravelling of the grisly murder of former Rwanda’s spy-in-chief Patrick Karegeya, the book offers the reader a kaleidoscope of a Mafia-like Murder Inc. hit squad that will go to any length to execute their mission, once the spotlight is shone on you. Once one-time Kagame’s bosom buddy, a kind of a special whisperer to the president’s ear, Karegeya spectacularly fell from favour, the spotlight would be turned on him.

After finishing serving an 18-month jail sentence in one of Kigali’s notorious prisons in November 2007, the 48-year-old spy who had just come in from the cold and who loved Rwanda, although he had largely grown up in Uganda, seemed unbowed. But one of his military intelligence friends had the head and sense of forewarning his beleaguered friend: ‘Listen, Rwanda’s not for you now, please skip it and head for the mountains – and quick.’ Karegeya heeded his colleague’s advice and headed for Kampala. But, not sooner had he landed in Kampala he was already travelling to Nairobi.

Yet, there was no respite for the man who once called the shots in the Rwanda’s ruling party RPF’s intelligence service. Karegeya would later tell the author, ‘I’d been warned that Kagame knew I was in Kenya and I was asked to leave for my own safety.’ It was an advice he did well to obey – but only just. Nine years ago, before Karegeya landed in Nairobi, the city had been the scene of a grisly murder of a former senior Rwandan cabinet minister, who had also fallen out with the all-powerful Kagame, who was, for all practical purposes, the de facto Rwanda President. It was therefore an ominous warning.

On May 16, 1998, on a hot and sunny Saturday, at about 5.00pm, Seth Sendashonga was being chauffeured by Bosco Kulyubukeye in his wife’s UN number-plated Toyota SUV, UNEP 108K, on Forest Road, today Prof Wangari Maathai Road. As Seth sat in front with the driver, a vehicle suddenly sped in front of their car, just at the junction of the Limuru and Forest Road and three men jumped out, firing at the duo. Seth died on the spot, as he logged a bullet in his head and Kulyubukeye died on his way to Aga Khan Hospital, a private hospital that is located up on Limuru Road, less than 500m from where the assassination took place.

Seth’s luck had incidentally run out. This was not the first attempt on his life. Two years before, on February 26, 1996, there was an apparent attempt to kill him in broad day light. Contacted by a family member who told him he had some juicy, confidential document that he wanted to pass onto to him, Seth agreed to meet the contact at Nairobi West shopping centre, off Langata Road, and five kilometres from the central business district. Seth came along with his nephew.

But Seth quickly sensed a trap and immediately asked for the document. It was not forthcoming. So, he turned to his car and that is when he saw the waiting two men standing next to his vehicle. The young men must have fumbled because, instead of immediately getting on with their mission, they asked Seth in Kinyarwanda if they could get a lift. Seth, instead, gave them some money; 70 Kenyan Shilling, but as he reached for his car keys, the two gunmen pulled out their guns and fired five bullets at Seth and his nephew. Seth ducked in a split of a second by falling to the ground crawling behind his car. The bullet, which had been intended for his head, caught his shoulder. His nephew, though was critically injured.

As he recuperated in hospital, Seth said he had identified one of his killers: Francis Mugabo, an attaché at the Rwandese embassy in Nairobi. Arrested by the Kenyan police, the Kagame regime refused to waiver his diplomatic credentials, as requested by Daniel arap Moi’s then government, so that he could face prosecution in court.

Two weeks after his assassination, on 3 May, a quiet Sunday afternoon, Seth had met Yoweri Museveni’s step-brother and his consigliere, Salim Saleh, in a secret rendezvous in Nairobi. Apart from being Museveni’s eminence grise, he was also the acting Minister of Defence. The meeting had been arranged by French historian Gerard Prunier. Prunier, an Africanist and a Great Lakes and Horn of Africa specialist was Seth’s friend and had been meeting him in Nairobi prior to his demise. Suffice it to say, this was not the first time Salim was seeking out Seth: On December 21, 1995, Salim has spoken to Seth over the phone and agreed to arrange a meeting.

‘Why kill Sendashionga? Why was that necessary?’

In Do Not Disturb Michela Wrong narrates a conversation between Karegeya and an East African businessman in a Nairobi five-star hotel that took place in 2003. The conversation centres around Seth Sendashonga: ‘Why kill Sendashonga?’, the businessman asked. ‘Here was this Hutu leader, a credible moderate, an important symbol of ethnic reconciliation, a man of principle – and you murdered him. Why was that necessary?’

Why was that necessary? According to Prunier in his book: From Genocide to Continental War, ‘what made Seth a dangerous man (was) because he embodied a recourse, an alternative to the parallel logics of madness that were developing and feeding each other in Rwanda.’

Michela has written a scintillating account of a murder most foul. The book cannot be described as ‘unputdownable’ – as is wont with ground-breaking books – because you must, now and then, put it down to soak in the horrendous facts. If journalists write some of the best everlasting books to be remembered for years to come – it is because Michela has exemplified the art: the book is both well-sourced and well-narrated. The language is crisp and unpretentious, the leg-work is indomitable.

Famously known as the author of, In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz, the racy account of Mobutu’s Zaire, Michela’s name will flash across many Kenyans’ memory as the writer of, It’s Our Turn To Eat, a book about John Githongo’s government corruption exposure, as the Permanent Secretary of Governance and Ethics in Mwai Kibaki’s government. It’s Our Turn to Eat, was read like Pambana or December 12 Movement – underground and resistance pamphlets written in the 1970s and 1980s, by Kenyan dissidents that were digested like contraband, away from the prying big eyes of the state’s aficionados.

Do Not Disurb, The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad, is published by PublicAffairs.