At first glance conservative Dutch politician Wybren van Haga and the left wing in the Netherlands have nothing in common. Not when it comes to fighting the global gap between rich and poor (Van Haga’s liberal VVD party, like the UK Tories and the US Republicans, wants that gap bigger); not when it comes to health and education (VVD, again like Tories and Republicans, wants less of that) and certainly not when it comes to migrants coming to the Netherlands. The Dutch left wing stands for inclusivity and human rights. Wybren and his VVD want to keep ‘Africans’ out.

Van Haga even went further. Going all out, he proposed on Dutch TV that ‘we’ (meaning, presumably, Dutch people) should stop ‘their’ (meaning African people’s) population growth and also that ‘we’ should no longer vaccinate ‘their’ children (assuming, probably correctly, that ‘we’ would not immediately be successful in stopping ‘them’ from having any babies at all). Besides the fact that not vaccinating children would not necessarily mean less children, but certainly more children with polio, deafness and brain damage, it is interesting that progressive critics of Van Haga, in their perfectly understandable pro-vaccination and pro-African-kids outrage, all seemed to miss the point that 'we' do not vaccinate 'their' children at all. Both Van Haga and his critics seemed to be arguing about 'us' stopping something that 'we' are not doing.

Planning African families and vaccination of African children are responsibilities of African governments, not 'ours.' The remarkable commonality in Van Haga's and his critics' statements was that both, however diametrically opposed, seemed to completely dismiss any African agency in African health matters. There may be vaccination projects run by NGOs here and there, but these operate in conjunction with and under the supervision of the national health authorities in the country in question. This may sometimes go well and sometimes not, but the accountability for failures lies with African governments, who should then indeed be held accountable. Many social activists in these countries do precisely that. They would like some support instead of being ignored.

Both Van Haga and his critics were only talking about 'us', as if African decision making and action do not come into it at all. Our migration destination countries and 'we' who live here are all that matters. We don't actually look at what is happening in Africa, good or bad; we simply dismiss all of it. We only ask if 'we' should let ‘them’ in. The fact that the nice people in the West say yes to that question is nice, but the underlying attitude is as dismissive and -dare I say it- disrespectful as Van Haga's "no, let's all sterilise them and let them die."

OK, not exactly as dismissive and disrespectful. But also lacking in true human solidarity. If we are all equals as human beings across the globe, then it won't do to talk about 'them;' no matter whether what is said about 'them' is positive or negative. It won't do not to ask 'them' anything in this debate.

Why do ‘we,’ firstly, assume that all of ‘them’ want to come and live here? Only very few in ZAM’s pan-African network fall in that category. Practically all the journalists, activists and creatives we liaise with are very busy building up their own countries. (The right wing, who always say that all migrants should go back to do precisely that, do have a point there. Many of ‘them’ would also probably love to stay and build, or go back and build. The thing is that it is difficult when your country is run by warlords and dictators who jail you or shoot at you. But more about that later.)

It’s time to bring back the discourse of international solidarity

Some of our African correspondents brave even warlords and dictators. Friends in Togo have been participating in the uprisings in their country against the kleptocrat and brutal Gnassingbé regime. Kassim Mohamed and Muno Gedi expose corruption, and fight for democracy, in Somalia and Kenya. Estacio Valoi in Mozambique documents plunder by generals and politicians in cahoots with international criminal traders. Valoi gets detained by soldiers and ducks poachers’ bullets every once in a while, but still, this is what he does. He does not want to live in Europe.

Not everybody is as brave as Valoi, Gedi, Mohamed or our Togolese friends. Many simply leave countries where violent kleptocrats reign. Yes, those who seek a better future should be welcomed and supported, but how many would choose to leave their communities and families for good if they would feel that there was a future for young generations right there?

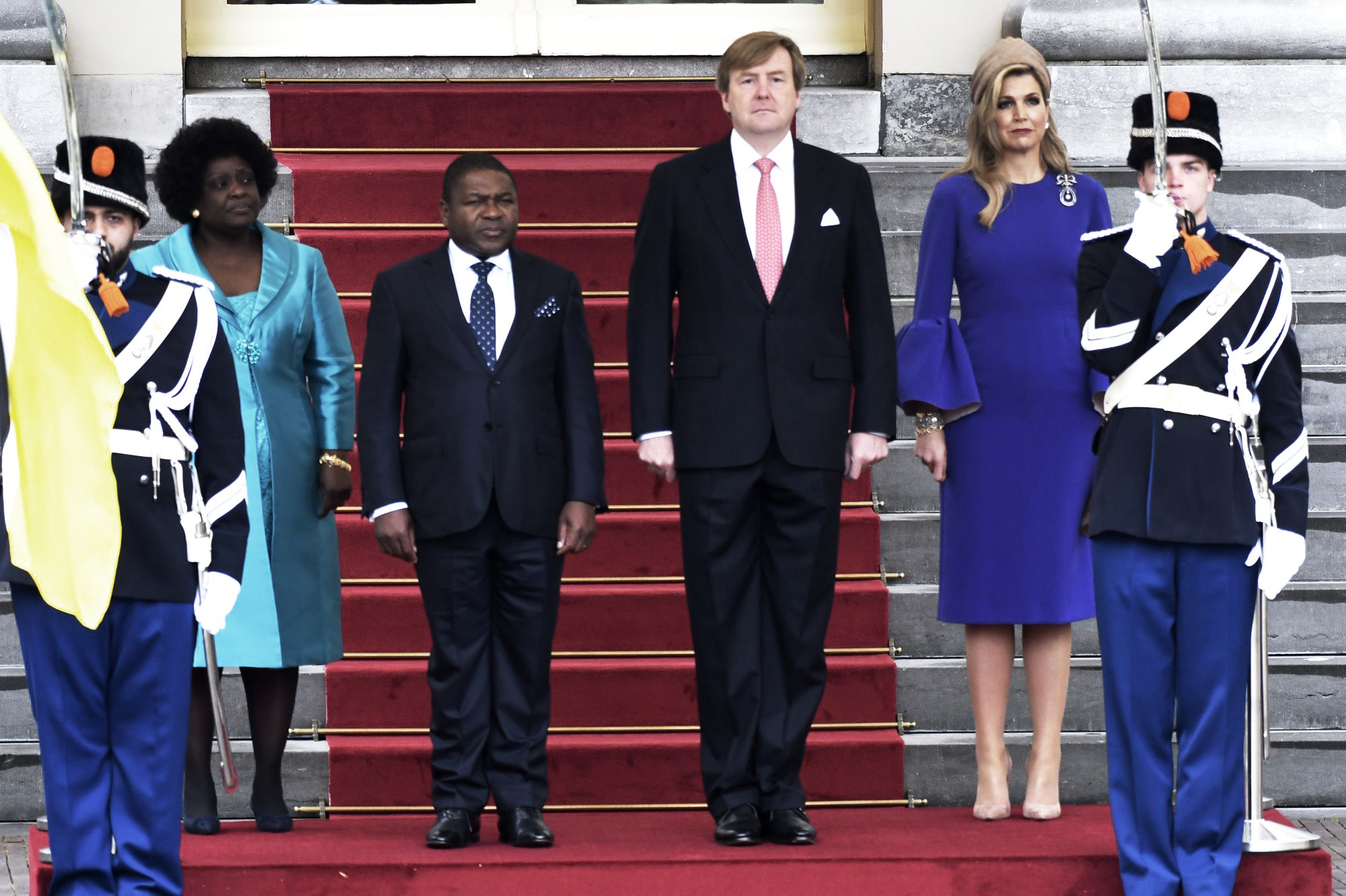

With all ‘our’ good intentions we ignore the kleptocrat dictator elephant in the room. Not only do we not support those who decide to stay and fight - does anyone even remember the term ‘international solidarity’? - ‘we’ often actively support the oppressors. ‘Our’ Royal Family, ignoring all reports of plunder by Mozambique’s nepotist regime, last year warmly welcomed its President. The World Bank’s infrastructure contracts help keep Togo’s oppressors afloat. Aid money fattens Somalias rulers. All that does is increase the despair. Practically all African investigative journalists have exposed how development aid often supports the bad guys, whilst the good guys seem condemned to scream into the void. They understand why their citizens aim to leave as long as that is the case.

The ‘international solidarity’ angle seems to have disappeared from western progressives’ discourse. I think it is time we bring it back.