A transnational investigation in Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Kenya and the DRC by the African Investigative Publishing Collective

Uganda chapter

Gulu Thursday February 16, 2017, 8 pm

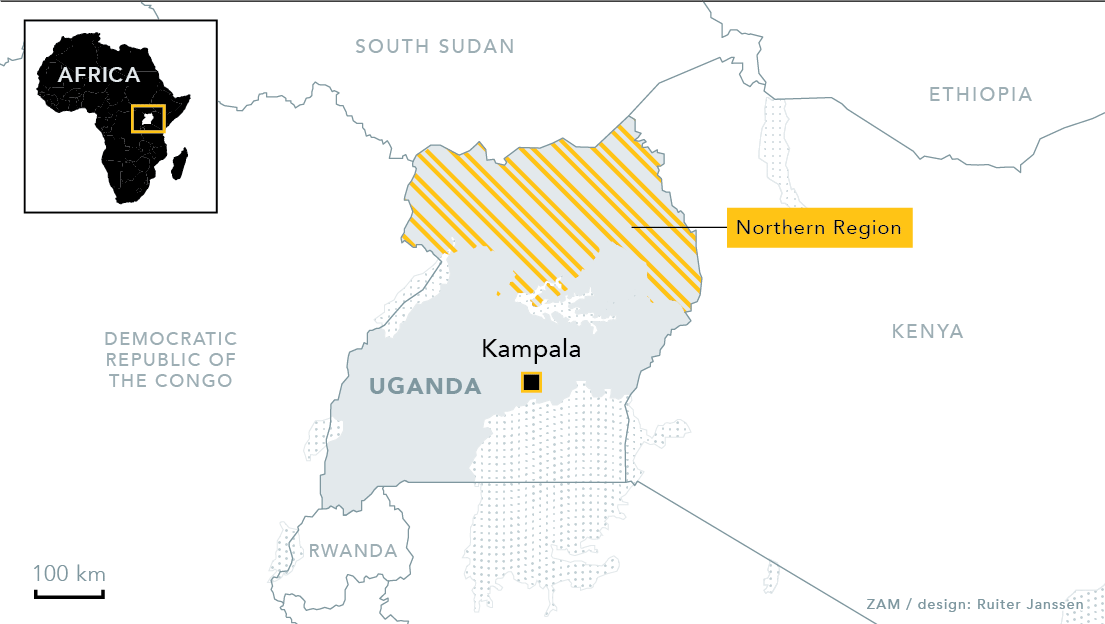

Outside Peyero bar on Gulu Municipality’s Langara road in north Uganda is a car which, by the last letter on its licence plate, belongs to State House, the official residence of the president. Upon inquiring I learn that both the bar and the car belong to Harriet Aber, the ‘social friend’ as she was called during parliamentary questioning time recently, of General Caleb Akandwanaho, (better known by his alias Salim Saleh), our president Museveni’s brother and a veteran of the war against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebellion led by Joseph Kony. It is this 20-year war that has left north Uganda devastated, with many people landless and destitute, and the object of large scale poverty alleviation and land resettlement programmes.

It is ironic that, of all places in north Uganda, I ended up in this bar. General Saleh is after all one of the problems here, if claims that he has been grabbing large chunks of land from the regional Acholi people are true. Land is the be-all and end-all of poverty alleviation in north Uganda. “The people need land to live on and to work, after years in refugee camps. No one here will develop without land,” the development organisations’ people have told me. Which is why land grabbing by the powerful -and not only Saleh, but also his ‘social friend’ Harriet, a lawyer as well as our bar owner, have been accused of such, as a ‘front’ for Saleh, as well as quite a few of their friends- goes directly against the objectives of any poverty alleviation in this region.

Saleh, Aber and others, -like Major General Charles Otema Awany, currently the commander of the UPDF reserve force and a brother to Richard Todwong, the deputy secretary general of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party and a former minister-, also have interests in big local and foreign businesses who want land. Well-connected sugar companies have used connections -that sometimes run up all the way to President Museveni himself-, to secure hundreds of hectares of land for their ventures. The group is regularly called out by locals for land grabbing, but court cases against them usually don’t go far. Their nickname is the ‘untouchables,’ after all.

Conflict entrepreneurs

All this is to say that one could have predicted that the ruling party’s large-scale poverty alleviation programmes, supposed to return people to the land after the war, were not going to be very successful as long as the ruling party’s big men were grabbing the same land. Then also, in June 2013, an investigation by the Public Accounts Committee of Uganda’s Parliament implicated several senior government officials in a scam that led to the loss of Shs 50 billion (about US$ 14 million). More than half of all moneys that donors had contributed to Uganda’s PRDP 1, meant to house and assist the landless and homeless refugees of the Kony war had been stolen outright by public servants and ruling party bureaucrats. There was an outcry among the donor community. UK, Norway and Ireland suspended aid and demanded money back; the World Bank said it would review its lending to Uganda. (1) +  OUTRAGED DONORS After finding out that donor moneys had been stolen by Ugandan ‘big men’ in 2012, several Western government released outraged statements. Check the one from Norway here. You can read here what the UK said and the news about the suspension of aid from Ireland is here. The World Bank said it would review its lending.

OUTRAGED DONORS After finding out that donor moneys had been stolen by Ugandan ‘big men’ in 2012, several Western government released outraged statements. Check the one from Norway here. You can read here what the UK said and the news about the suspension of aid from Ireland is here. The World Bank said it would review its lending.

Theft of donor moneys was however not the only problem with the PRDP. US$ 14 million was only a small part of the total of US$ 660 million that was dedicated to the overall plan over three years and that included police and justice build-up, roads infrastructure, water and sanitation as well as resettlement on the land. But the remaining US$ 646 million, though it had helped build some roads and other infrastructure, had also fallen into the hands of powerful elite figures, called ‘conflict entrepreneurs’ by University of Tennessee graduate Elliott Bertasi in his research thesis on the PRDP. Detailing how these ‘entrepreneurs’ had appropriated projects and contracts, whilst establishing often oppressive state power in the region, Bertasi concluded that north Uganda “may have been better off without it (2).”

Most of the culprits in the PRDP corruption scandal are still ‘big men’ today. Though the government audit report pointed an accusing finger at Secretary to the Treasury Keith Muhakanizi, Accountant General Gustavo Bwoch, Commissioner Treasury Services Isaac Mpoza, as well as the Permanent Secretary in the Office of the Prime Minister Pius Bigirimana and the accountant in the same office, Geoffrey Kazinda, only Kazinda was prosecuted and jailed on corruption-related charges. No charges were brought against all the others. Muhakanizi is still Secretary to the Treasury as well as Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Finance. Bwoch retired honourably. Bigirimana was transferred to the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, where he now presides over an equally large budget, including the US$ 71 million Youth Livelihood Programme, a five-year initiative that is being managed in a similar fashion to the PRDP (3).

There is a PRDP II under way, now, and also a Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (already into its third sequel.) But, whilst observers are skeptical that these programmes will yield any more result than PRDP I and NUSAF 1 and 2, all donors have come back again in the meantime, often stating that they have noted a ‘new commitment’ in Uganda to fight corruption.

However, a new European “Programme for North Uganda” launched in 2016 makes note of, once again, a ‘high risk of capture by local elites (4).’

Riding boda-boda

Meanwhile, the grassroots in the tormented region battle on. Most people have, one way or another, and mostly without help, successfully retired to small plots of land, where they have resumed farming and trade. Some small NGOs who were on the ground with programmes destined to help the over 66 000 returned child soldiers with training for things such as basket weaving and bricklaying are changing focus. Richard Kinyera, a former child soldier who was trained as a bricklayer and indeed did bricklaying for 11 years, now rides a ‘boda boda’ motorcycle taxi, with the largest percentage of his earnings going to the taxi owner. Asked why he changed careers, he simply says he started to feel a ‘loss of enthusiasm’ for bricklaying.

NGOs did care for returned child soldiers when the state didn’t, and land advocacy organisations ACORD and “Gulu Women’ Economic Development and Globalisation,” Gwed-G, successfully helped settle land disputes between local individuals and communities. Magdalene Abalo, for instance, from Atiak village in Gulu district, couldn’t have returned to her plot after years in an Internally Displaced People’s (IDP) camp, without the mediation efforts of the NGO’s. “(My land) was taken by a rich neighbour,” she says. (“That neighbour) was taking advantage.” But ACORD helped to convince the lady in question.

Yet, Elly Turuho of ACORD and Pamela Judith Angwech of GWED-G admit that their efforts are limited to disputes between local community members. When, early January, at least one thousand Gulu residents received letters from municipal authorities giving them a fortnight to vacate their houses to pave way for a new World Bank-funded roads expansion project, both ACORD and GWED_G decided not to get involved. Angwech mentions “some of the political leaders (here) (who) are used as entry points (for land grabbing) because of their upper hand in decision making processes,” as people her organization cannot easily stand up to. “These are sensitive issues,” says, also, Turuho. “To be honest we have not dealt with evictions.”

Bread and butter

Fear of the local political leaders among smaller NGOs is real: they can make things very difficult for you by simply accusing you of non-compliance with regulations. Most NGOs don’t comply with one thing or other: of the roughly ten thousand NGOs in Uganda only a third are in operation and of the five hundred NGOs in Gulu district alone, only eighty-five fulfill all the requirements. But authorities often don’t have a problem with the NGOs that are really fraudulent, such as the one that solicited funds from parents for ‘scholarships,’ then took the children and abandoned them on the streets of the capital Kampala. The ones that are targeted for being ‘irregular’ tend to be the ones that are too critical.

The strong language of Minister of State Grace Kiyucwini, who told me in an interview that “NGOs should work with government (…) and re-orient their plans to support (the PRDP and NUSAF programmes),” was not talking about inefficient or fraudulent NGOs but about “those who work for their own thing” or “say one thing whilst the government says another.” Development studies lecturer Christopher Oyat, who has extensively researched development work in north Uganda, says that there is a real fear among NGOs to ‘challenge authority.” “They don’t go full blast on human rights and bad governance, and that means problems will continue. (…) They want to protect themselves because of their bread and butter issues and I find that a serious indictment on the NGOs.”

NGOs do have a lot of bread and butter to lose. Their salaries are mostly around three times the amount of money a local employed in a similar job would earn; the vehicles are usually way better and more expensive than those purchased for similar purposes by the government and the same goes for their staff’s houses. That is way more to lose than, for example, the women of Amuru district who threw off even their clothes when they marched, naked, in protest against a planned demarcation of land that would have granted large portions to be taken by big business. Nevertheless, their protest -once in 2012 and once in 2015- was effective: the land demarcation is still on hold and their communities are still on their land.

There is a strong belief in Acholi culture that a woman can bring a curse on her enemies by stripping in public and local political leaders were reportedly terrified of what these women were doing. But meanwhile, there have been other successful protests too. The communities that complained about eviction attempts by ‘social friends’ Harriet Aber and General Saleh in 2016 made it -fully clothed- to NTV and even got the agriculture minister to put the evictions on hold. Perhaps inspired by these communities’ own protests, GWED-G recently announced that they will extend land rights training and loans to the women of Amuru.

The loans in particular should be more than welcome. A UNDP poverty and human development index found, in 2015, that whereas there had been a little improvement in poverty percentages in the north generally since the ending of the Kony war, in the most damaged area of the north there had been a downward trend again with ‘income constriction’ in the most damaged area (5).

Click here for the other country reports: Cameroon, DRC, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Uganda

- www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Donors-cut-Shs70b-aid-over-OPM-fraud/688334-1603888-bqrh4yz/index.html

- www.documentcloud.org/documents/3856482-Post-Conflict-Reconstruction-and-Development-the.html

- Mpoza died in August 2016.

- www.documentcloud.org/documents/3858641-EU-Programme-North-Uganda-2016.html

- www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Poverty-on-the-rise-in-northern-Uganda---report/688334-3000650-14l26ilz/index.html and www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Poverty-on-the-rise-in-northern-Uganda---report/688334-3000650-14l26ilz/index.html