‘How do you remove a dictator from Amsterdam?’ asks a tweet, posted after an audience of two thousand in the Royal Carré Theatre in the Netherlands is fired up with righteous anger at the actions of Uganda’s autocratic leader, General Yoweri Museveni. It is November 12th 2022 and the crowd has just seen a documentary about the thwarted presidential bid of Ugandan opposition leader and Afrobeat star Bobi Wine, who attended the screening. The film portrays the ongoing oppression and torture of political opponents in a country whose president, General Yoweri K. Museveni, has been in power since 1986. The movie, titled The People’s President, is declared a ‘gripping story of resilience, sacrifice and courage in the face of great injustice’, according to a review on a Dutch news site, which went on; ‘People cried, got angry and were shocked at what happens in Uganda’.

‘People cried, got angry and were shocked at what happens in Uganda’

The screening in Carré prompts dozens of tweets from the Netherlands and elsewhere expressing outrage about the Ugandan situation and solidarity with the opposition, embodied in this case by Robert Kyagulanyi, a pop star better known by his stage name, Bobi Wine. One of 30 children of a veterinarian and raised in the deprived Kamwokya neighbourhood of central Kampala, Wine rose to fame by styling himself as ‘the Ghetto President’ and singing songs in Luganda about politics and the plight of those in the ‘ghetto’. Some tweets from Uganda express a hope at the sentiments coming out of Amsterdam. ‘Through this film, the world is getting to know the criminal enterprise which rules over our country Uganda!’ writes one. But after the question is asked about how a dictator might be removed by people sitting in Amsterdam, spirits are somewhat dampened.

How do you remove a dictator from Amsterdam, indeed?

An ageing resistance movement

In Uganda, repression by the ageing Museveni’s 37-year-old National Resistance Movement regime is only intensifying. The country is home to one of the world’s youngest populations, with 77% of citizens below 25 years old. They’re increasingly urbanised, disaffected and resentful, chafing under a securocrat state that has delivered little in terms of services such as healthcare and education. But protesting is risky, as the movie shows; dissidents live under the threat of abduction by state agents driving unmarked vehicles known as drones. Once captive they face torture, potentially indefinite detention and even death, and according to Wine, over a thousand of his followers have been abducted, detained and some tortured. Wine himself has also been arrested and tortured several times, while his driver was murdered in 2021 and recently, on November 5th 2020, his bodyguard Jamshid Kavuma vanished and has still not resurfaced.

Insulting the person of the president

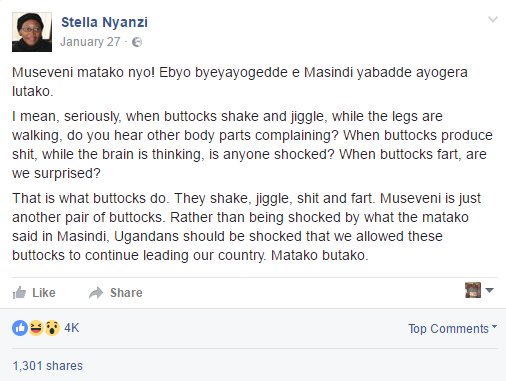

For increasing numbers of social media-savvy youth, however, simply shutting up is not an option. Access to Facebook, Twitter, TikTok and other platforms means seeing what life is like in more developed parts of the world. Meanwhile, the deference formerly granted to powerful figures has been replaced by instantly accessible information and memes about their age, corruption and incompetence. Hence the crowds of thousands who follow the posts of rebellious academic and poet Stella Nyanzi as she unapologetically refers to Museveni as like a pair of buttocks ‘that just jiggle, fart and shit’, or the audiences who read the writings of novelist Kakwenza Rukirabashaija, with their evocative titles like ‘Banana Republic’ and ‘The Greedy Barbarian’.

The tweet led to detention and severe torture

The two have both paid a high price for their outspokenness, however. Nyanzi spent repeated stints in jail and faced a lengthy trial for the crime of ‘insulting the person of the president’. Rukirabashaija made an ill-advised tweet in which he mocked Museveni’s son and presumed heir, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, describing him as ‘obese’, ‘with humongous hips and breasts’, and asking how ‘a soldier …can have ‘such a sedentary’ body before stating that ‘God punishes the corrupt in a good way with (..) a stupid figure’. The tweet led to his detention and severe torture, during which he described having been beaten for days and flesh ripped off his legs with pliers. Both writers have since gone into self-imposed exile and taken up residence in Germany.

Torture is officially illegal in Uganda, but while Rukirabashaija faced a speedy trial for his insults, his countersuit for torture has yet to be heard in Uganda’s High Court. This should come as no surprise: President Museveni appoints all judges, typically favouring those who align with his nationalistic rhetoric about Uganda’s independence and the corrosive influence of ‘the West’, which, he says, is supporting the opposition. As a result, even when faced with compelling evidence implicating members of all branches of the security forces in illegal acts, only light penalties have been sporadically applied to those convicted. Commenting on such cases, Museveni has stated that torture is not widely used in Uganda and is the preserve of a few old officials with ‘colonial mindsets.’ However, rather than throwing his weight behind investigations into such practices, the President also recently called for the judiciary to be even more aligned with government ‘values’.

Phone hacking

A broad policy of repression has also been granted new tools in recent years, especially in the field of social media surveillance. In December 2021, diplomats at Kampala’s American embassy found that their phones had infiltrated with the notorious Pegasus hacking software, which had been sold to the Ugandan state by Israeli arms manufacturer NSO. The program can infect iPhones without the user’s knowledge, snooping on everything from voice calls through location data to encrypted chat messages. Eight months later, in August 2022, the Israeli daily newspaper Haaretz reported that another Israeli company, Cellebrite, had sold the Uganda Police Force technology that would allow them to hack into cell phones. In a statement, Cellebrite did not deny the sale but claimed to be ‘scrupulous’ about the legal and ethical use of its products.

An olive-and-black shirt led to a charge of ‘impersonating a soldier’

The Ugandan authorities are also buttressing their digital eavesdropping with an ever-widening suite of legal options to be used against those critics unfortunate enough to come to their attention. While Kakwenza Rukirabashaija’s tweet was enough to have him charged with ‘disturbing the peace of a person’, in October 2022 a charge of ‘impersonating a soldier’ struck a relative of US-based Ugandan journalist and pro-democracy campaigner Remmy Bahati after appearing in a group photograph alongside Bahati while wearing an olive-and-black shirt. The charge formed the pretext for abducting and detaining a group of five of Bahati’s relatives for several days. They were only released after Bahati leveraged her large social media presence to coordinate a publicity campaign against the abductors.

Banning Google search

A relatively new legal instrument used for muzzling opposition is the recently amended ‘Computer Misuse Act’, which Stella Nyanzi’s expletive-laden rants were charged under. Minor TikToker Teddy Nalubowa was imprisoned under the same law after she recorded herself cheering the news of the death of former Security Minister Elly Tumwine. New amendments to the Act bring social media more explicitly under its auspices, with up to ten years in jail awaiting those convicted of spreading ‘unsolicited, false, malicious, hateful and unwarranted information’. It also outlaws ‘without authorisation’, accessing ‘another person’s data or information, voice or video records’ and sharing ‘any information that relates to another person’, which effectively criminalises internet searches into individuals.

Malicious acts

Even money-laundering laws have been used against activists. On December 22nd 2020, with the country preparing for elections on January 14th 2021, Ugandan lawyer and human rights defender Nicholas Opiyo found himself being arrested along with three of his colleagues and a member of the opposition after his legal charity, Chapter Four received money from external sources. While having lunch at a restaurant, he, three lawyer colleagues and a member of the opposition were taken by plainclothes officers, handcuffed and driven off in an unmarked van with tinted windows. They spent eight days in detention before being charged with money laundering and ‘related malicious acts’ and released on bail. The charges were quietly dismissed more than a year later.

The US$ 340,000 that was the subject of the money-laundering charges had been made available by donors for Chapter Four’s efforts to ‘promote open government, defend human rights, strengthen civil society and facilitate the free flow of information and ideas’. The donation had presumably caught the attention of the authorities because the state’s National Bureau for Non-Governmental Organisations had recently suspended Chapter Four, along with 54 other civil society groups, to limit precisely these sorts of activities. The CSOs’ permits had been suspended in August 2020 based on a range of administrative charges including operating with expired permits and failing to file annual returns and audited books. The move appears to have been a reaction to dossiers being filed by intelligence agencies which accused them of harbouring ‘neo-colonial agenda agents’ and seeking to provide financial support to the opposition ahead of the election.

The fund that assisted civil society activities was abolished

In the same month two such ‘agents’ found themselves unable to continue to work in Uganda. First the EU advisor on elections, Simon Osborn was expelled. Osborn was previously an officer at an American NGO with close ties to the US government and was in charge of disbursing budgets for civic education and election-related activities. Then, two weeks later, Dutchman Marco de Swart, who was in charge of election campaigns at a multi-donor fund for civil society in Uganda, was blocked from re-entering the country. The fund itself, called the Democratic Governance Facility, which had assisted countless civil society activities, would be abolished a little while later.

The Kingdom of the Netherlands

Undeterred, the opposition nevertheless managed to continue to organise protests demanding an end to Museveni’s reign, culminating in marches in central Kampala in November 2020. Caught on the back foot, the Ugandan security forces responded with unprecedented violence. Battle-hardened units of soldiers brought back from a deployment in Mogadishu unleashed tactics normally suited to controlling an insurgency. In the city’s narrow streets, they killed about a hundred citizens.

At the same protest, police vehicles could be seen marked ‘with funding support from the Kingdom of the Netherlands.’ The image, so shocking that it made headlines in the Dutch Volkskrant newspaper at the time, perfectly illustrated the bind in which Uganda’s Western ‘development partners’ find themselves. While they remain committed to supporting pro-democracy civil society movements, the West also retains a pragmatic relationship with the Ugandan state, which is seen as a pillar of stability in an otherwise volatile region. It thus finds itself forced to extend aid that, though earmarked for health, education and other public services, also frees up funds that the government can then spend on tanks, vehicles and weapons. Unsurprisingly, despite their frequent nationalist and anti-Western rhetoric, Museveni’s government appears to have few qualms about accepting such aid.

'Don’t spend on a corrupt government’

Godber Tumushabe, the Associate Director of the Great Lakes Institute for Strategic Studies (GLISS), said in an interview that it is vital for donors to support democracy more than repression, and that ‘aid for health and education’ cannot be the only criteria. 'Already, the health sector is ailing and education is less than first class’, Tumushabe said. ‘You can only improve on these if you have a functional government.’ He suggested donors should put funds ‘directly in the hands of private sector and citizens rather than spending these on a corrupt government.’ As another alternative, he suggested placing sanctions on ‘individuals who are abusing human rights and spending their corrupt loot roaming the world and giving a good education to their children abroad’.

Civil society activists and opposition leaders in Uganda describe feeling disempowered by what they describe as the ‘propping up’ of the regime by the West, demanding that development partners ‘Stop Paying our Oppressors’. However, they also fear that the few services the public in Uganda can access would be the first to disappear if donors pulled out. This is why a previously absolutist position demanding the full suspension of funding was recently revised to explain that Ugandan government aid should be stopped ‘in all but the most basic humanitarian sectors’. Meanwhile, pro-democracy activists suffering financial strangulation by the state continue to request funding for their activities. ‘Because even when you do your community work voluntarily, you still need money for transport and data’, said one.

Footnote

On January 10th, 2023, the Constitutional Court in Uganda nullified section 25 of the Computer Misuse Act. It is a victory for human rights activists Andrew Karamagi and Robert Shaka, who had filed a petition to this effect. This specific section had been used to charge and detain activists Stella Nyanzi and Kakwenza Rukirabashaija.

Emmanuel Mutaizibwa is the political and investigations editor for the Nation Media Group in Uganda, and is also the co-founder of the East African Centre for Investigative Reporting Ltd (EACIR), which is published through Vox Populi. He has produced films with organisations including Insight: The World Investigates, Al-Jazeera, TRT World and, more recently, with Vice and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). He has also written for South Africa’s Sunday Times and the London-based Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). Having recently seen colleagues arrested ‘on the whims of powerful individuals’, he comments that one ‘needs an intrepid spirit’ to continue to do investigative journalism in his country.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Cry Freedom | Trends of repression and resistance in five African countries

Nigeria | Death by tax collector by Theophilus Abbah

Cameroon | The truth is a dangerous business by Chief Bisong Etahoben and Elizabeth BanyiTabi

Zimbabwe | No human rights for ‘bad apples’ by Brezh Malaba

Kenya | The hidden cost of free and fair by Ngina Kirori

Human rights violations 2017-2022 in Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Kenya