1. General

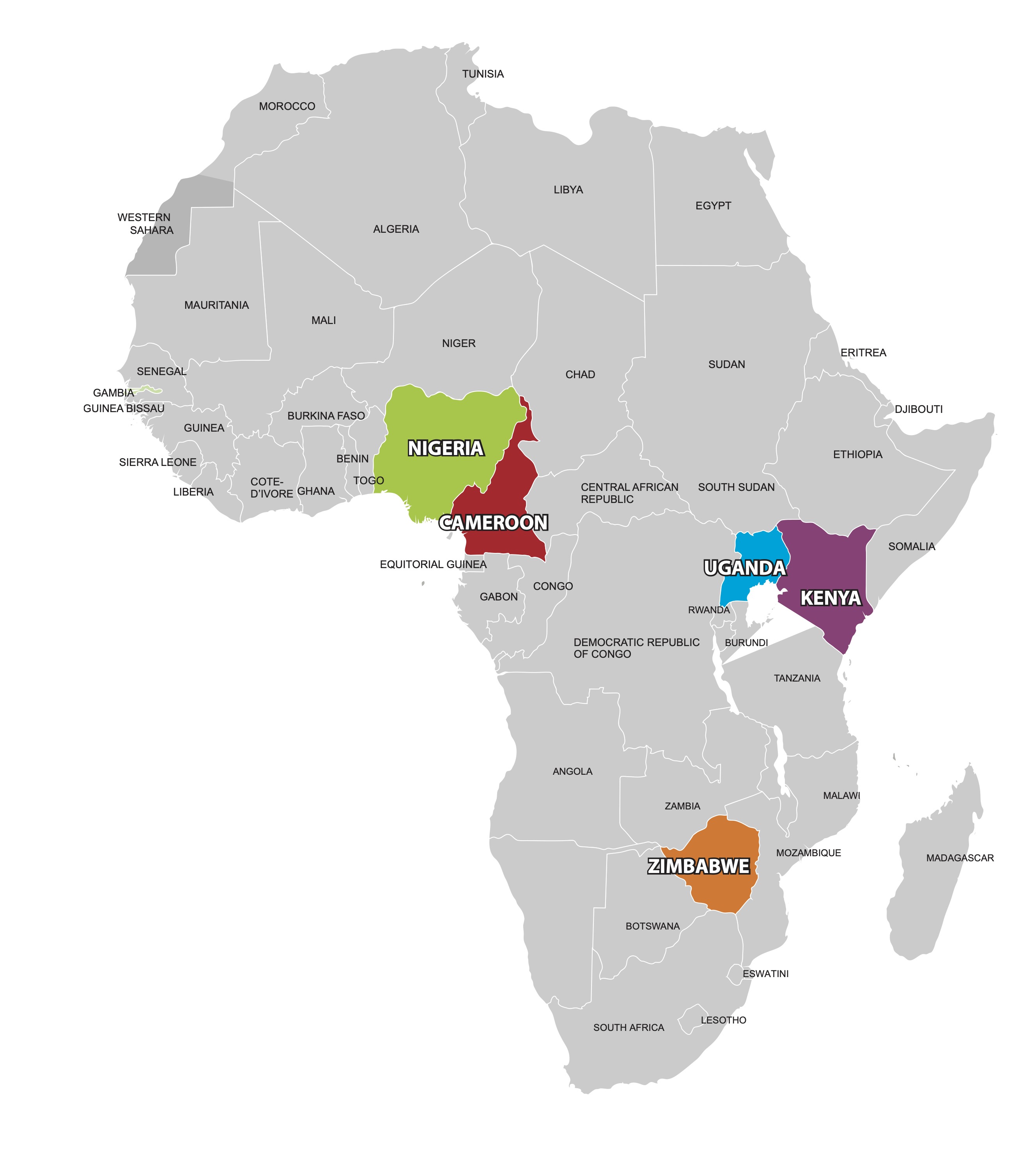

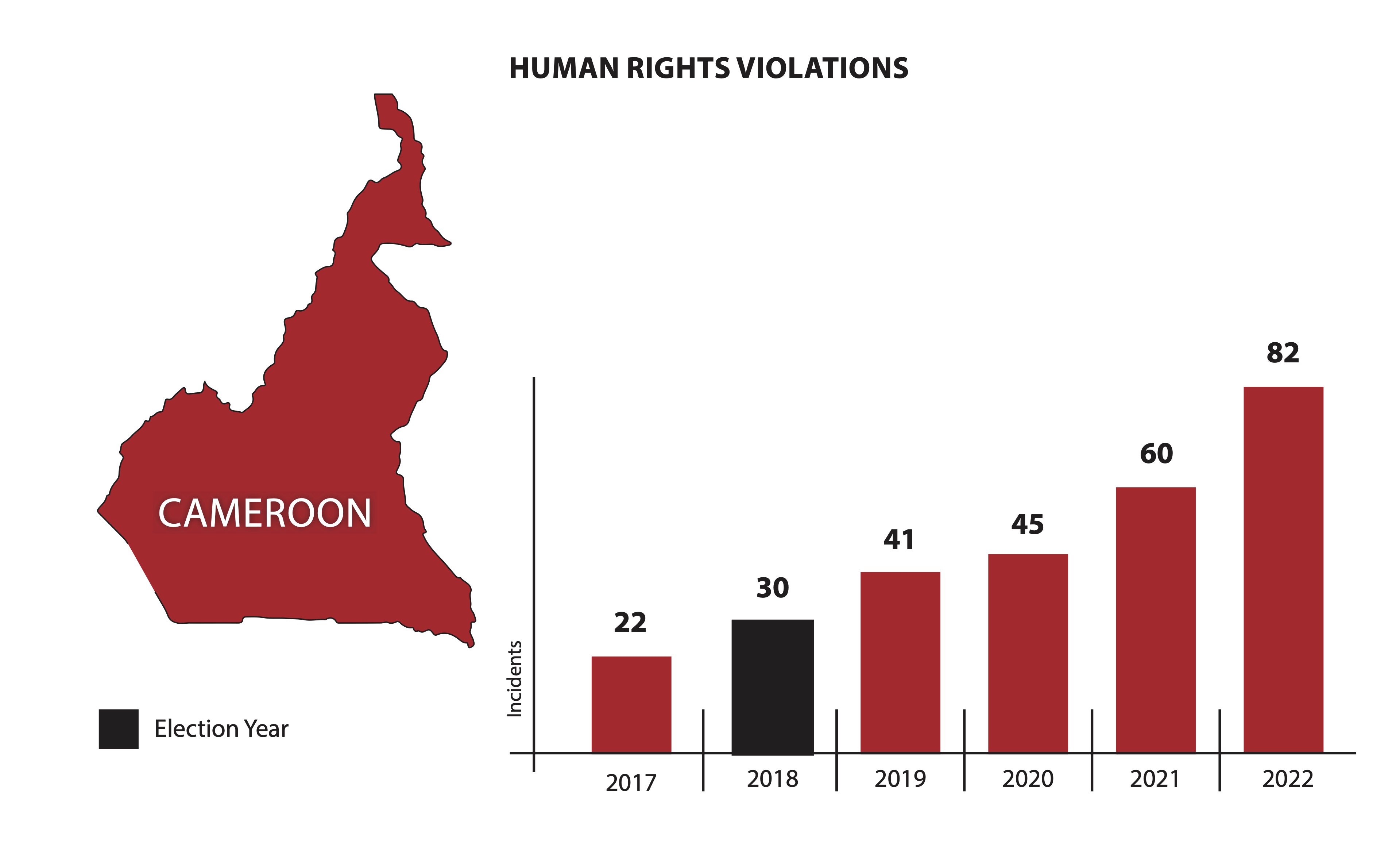

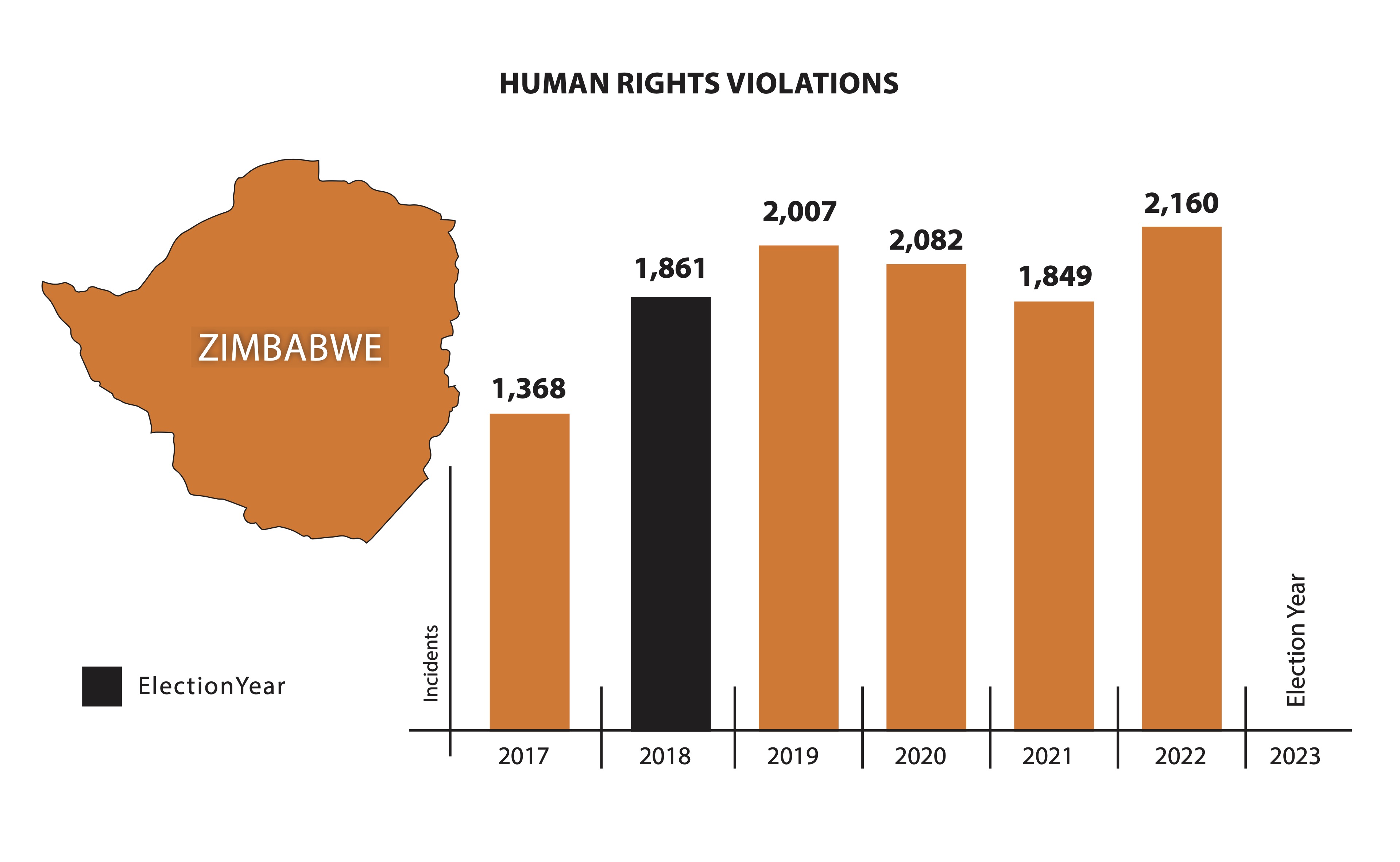

Data on human rights violations collected over the past five years appears to show a marked and steady increase in the use of state and state-sponsored violence against, and arbitrary arrest and detentions of, political opponents and critics in Cameroon and Zimbabwe, while in Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria state violence has tended to peak during elections, often securing wins and new terms for the orchestrators, before diminishing again afterwards.

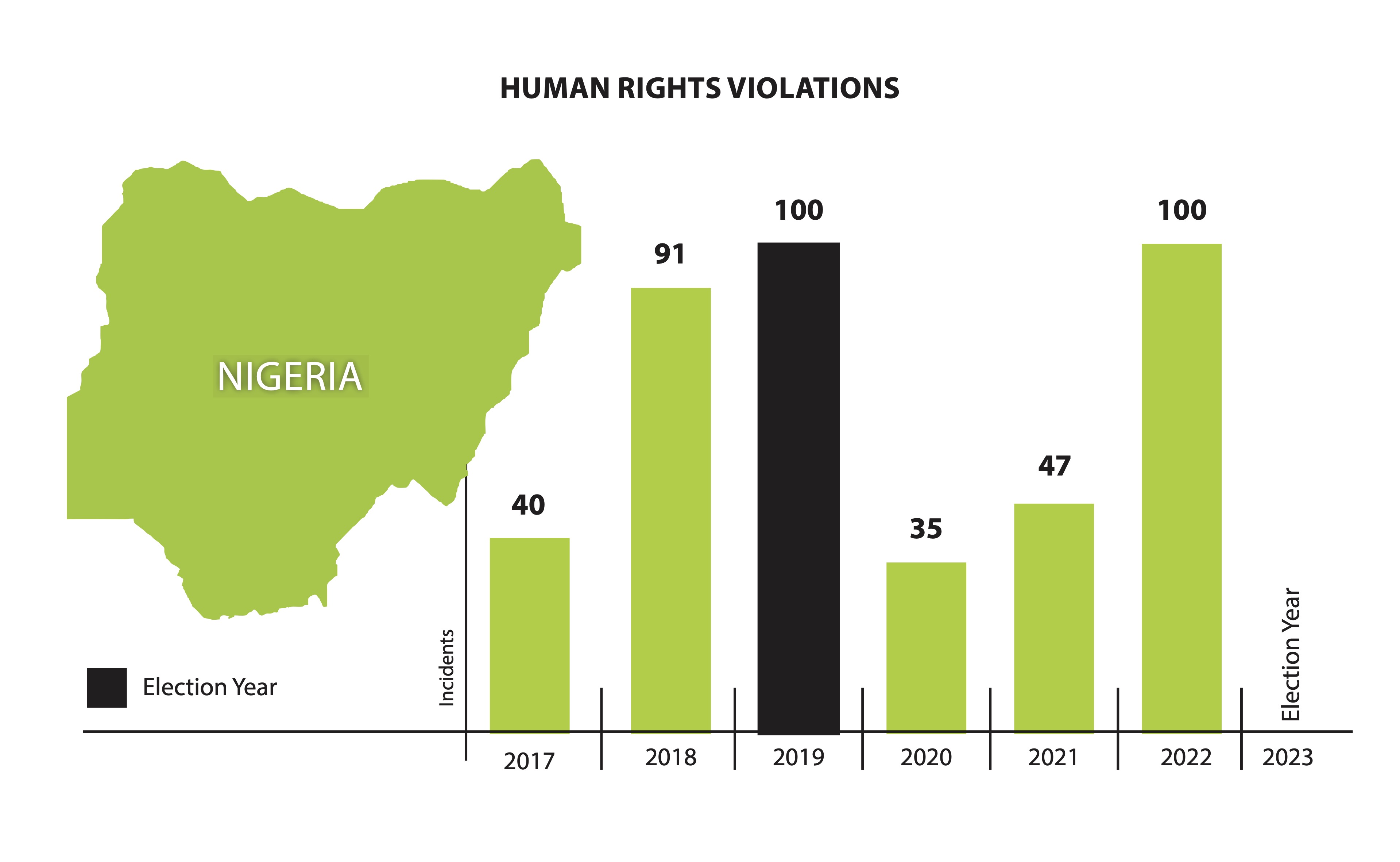

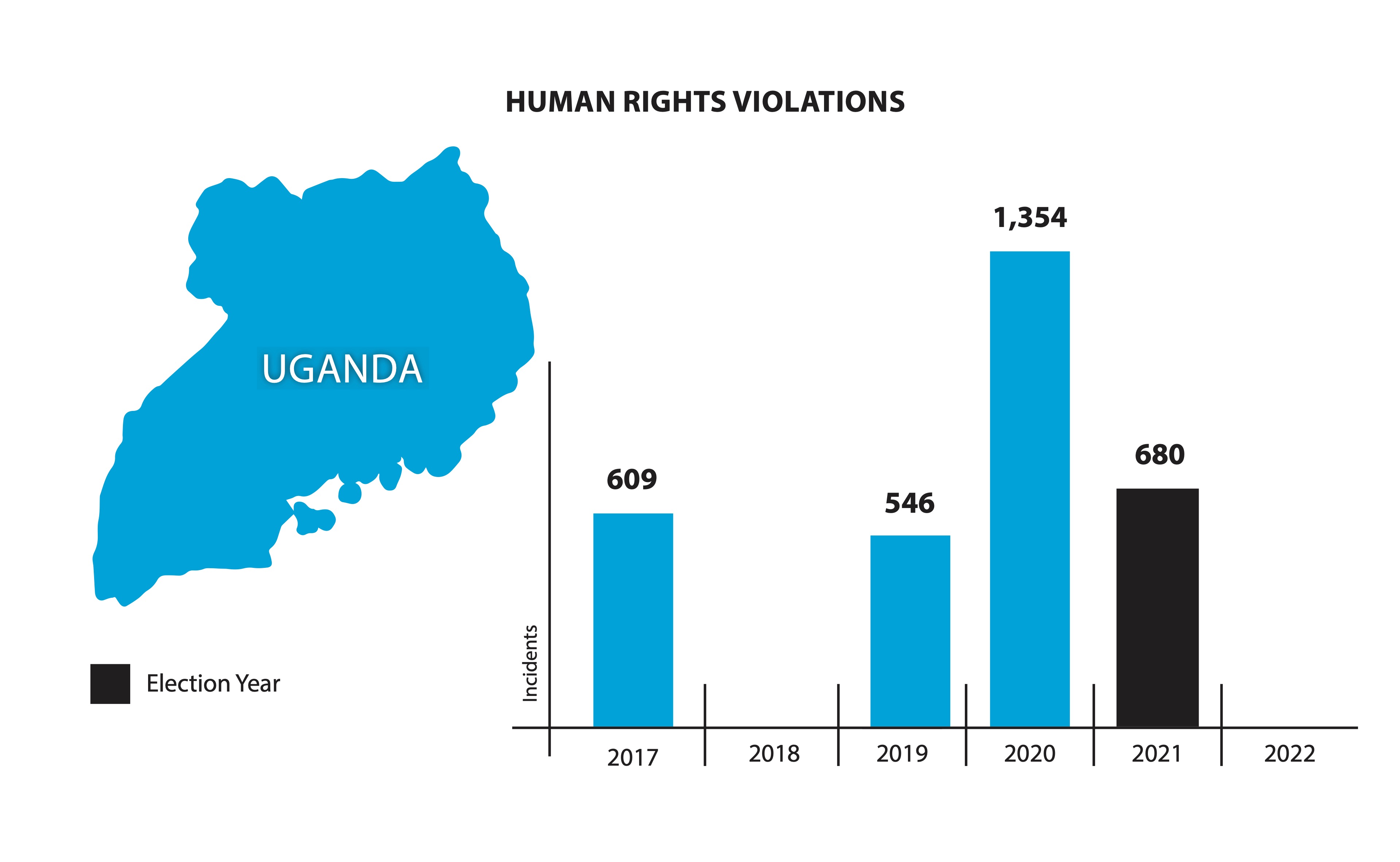

Repressive violence in Nigeria has been high throughout - with some peaks and dips - over the past five years, but attacks on activists, which we presume to be motivated by political reasons, are on the rise again there in the run-up to elections in 2023. In Uganda, the data was insufficient to indicate trends but even aside from the clear peak observed around the elections in 2021, which delivered another term for autocrat ruler Yoweri Museveni, repression of opposition under Museveni’s securocrat state appears to remain high. Only in Kenya do state repression numbers appear to have decreased, reflecting the more peaceful elections in 2022 when compared to 2017.

The COVID-19 pandemic influenced the data in different and sometimes contradictory ways in 2020 and 2021. In Nigeria, the banning of protests under the pretext of COVID-19 rules resulted in relatively lower numbers of attacks on individual activists in those years, while in 2020 scores of Kenyan citizens were arrested and detained for protesting the embezzlement of COVID funds. In Zimbabwe, many social justice activists were detained in 2020 for ‘breaking COVID rules’ while in 2021 more people stayed at home under the regulations. In 2022, with the 2023 election season underway, political opposition activity increased again, resulting in new state clampdowns. In all five countries, numbers tended to increase more during election years, or in the months of the previous year when elections were scheduled early.

2. Criteria

In this survey, we documented only reported incidents of politically-motivated state or state-sponsored action against individuals which violated accepted human rights standards. Such individuals could be political activists, intellectuals or journalists, as well as their relatives, neighbours and friends if the action taken against the latter appeared to be motivated based on their relationships. State action taken against individual members of armed oppositional groups was also counted, as long as the action was a clear violation of human rights and rules of war, for example in the case of an extrajudicial killing of a suspected militant who posed no threat at the time of the incident.

More explicitly, the incidents counted included:

- Politically-motivated arrests and detentions; imprisonment without bail and torture

- Assaults, abductions, attacks on homes or offices, abduction and murder by state actors

Assaults, abductions, attacks on homes or offices, abduction and murder by state-sponsored actors such as ruling party members and mercenary recruits of state structures, ruling parties or political authorities

- State-enabled intimidation, including the withholding of food, medical aid or free movement as a punishment for political opposition

Not counted in the main data charts were cases of:

-The hurt of individuals as a result of police or army action against mass protests because casualties in those conflicts often include bystanders

- Casualties resulting from the confrontation between the state army and armed rebel movements

- The hurt of individuals for non-political reasons

- Verbal threats unaccompanied by real punitive action (a threatening phone call was insufficient grounds for inclusion, while we did count the withholding of food aid to opposition areas in Zimbabwe)

Disclaimer

It was often difficult to find analytical data support in the countries where we worked, while the local human rights NGOs which provided us with the source data also use different methods and criteria in their reporting. The NGOs themselves also often don’t have extensive surveying capacity and frequently rely on cases being reported to them. We tried to mitigate this by also searching media reports, taking care not to double-count, but this exercise is still likely not to have succeeded in counting all the human rights violations that occurred in any of the countries at any given time because we were unable to count incidents which did not result in some form of media coverage.

Each NGO followed its own criteria in collecting data, which shapes the outcome. Some count verbal threats, for example, while others don’t. Some mix attacks targeting journalists with those on other citizens, while some count these separately. Some don’t distinguish targeted human rights violations of critics and opponents from general human rights violations of citizens, for instance in cases where the police claim that a victim was a criminal. Some count violations by the state or state-sponsored actors together with other violations committed by rebel groups, gangs or criminals. We took care to only select those that complied with the criteria of state action for political reasons against targeted individuals, journalists included.

Some anomalies were difficult to mitigate because political repression within, and between, different countries manifests in different forms. Oppressive actions in Zimbabwe often target individual opponents. In Cameroon, where the police and army sometimes carry out mass arrests and have been accused of responding to an insurgency by ‘cleansing’ entire villages and neighbourhoods through massacres and arson, one reported ‘incident’ may include many victims. The data on ‘incidents’ can therefore not be understood to be equal to the number of victims. Cameroon may rank below Zimbabwe in the number of incidents, for example, and yet the total number of victims may be similar.

For its part, in Uganda, the difference between the number of human rights violations counted by NGOs and more in-depth reports compiled by parliament and the opposition is so vast that we could find no way to compare these. We opted to only highlight the numbers from the parliamentary and opposition reports since these seemed more comprehensive. We listed the years where these reports applied and left the numbers for the other years blank. A blank year does not, therefore, indicate an absence of repression- only an absence of data.

We owe a great debt to Kenya-based data expert Purity Mukami, who came to our rescue towards the end of our collection exercise and helped us bring order to a sprawling dataset.

Individual legends

Nigeria: data from Human Rights Watch, media reports and the Abuja-based Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) associated with the Premium Times, included incidents of politically-motivated intimidation, assault, kidnapping, arrest, detention, murder, and arson by state actors and associated vigilantes and mercenaries. Numbers rising in 2022 have been linked to upcoming elections in 2023.

As in other countries, the ZAM team did not include victims of police and army action in clampdowns on mass protests in the data charts. Such clampdowns included the 2020 state clampdown on #EndSARS, a mass movement demanding the disbanding of a police unit notorious for its brutality. The army was sent to disperse protesters gathered at the Lekki toll gate in Lagos, resulting in scores of deaths and many more injured. Because of our focus on targeted individual attacks, which excludes the hurt of individuals who may be bystanders during police or army action against mass protests, these victims have not been counted in the Nigerian data chart.

Cameroon: data up to and including 2021 was from Human Rights Watch (HRW). For 2022, since HRW’s report for that year was not issued at the time of writing, we relied on data from the Cameroon- based Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA.org), whose methods and criteria are largely similar to those used by HRW. Both organisations count incidents of politically motivated intimidation, assault, kidnapping, arrest, detention, murder and arson by state actors and associated vigilantes. This use of ‘incidents’ as a marker however, combined with the fact that Cameroonian state violence - especially in the Anglophone conflict zones - often takes the form of massacres and arson, resulting in a relatively low number of registered incidents when for instance compared with Zimbabwe, where ruling party mob violence is often directed against individuals. In the end, the number of victims in Cameroon may be many times higher than the number of incidents.

The number of arbitrary arrests and detentions in Cameroon may also be higher than recorded because incidents such as the mass arrest of an estimated 500 citizens at a protest in 2020 were counted as one incident. Human rights activists put the country’s total number of political prisoners at over 3,000.

Lastly, the full count in Cameroon in 2022 may also be higher than indicated because we could not find a report for the month of July in that year.

Uganda: available data was derived from a Parliamentary report in 2017 as well as reports compiled by opposition organisations in 2019, 2020, and 2021. We could not find comprehensive data for 2018 or 2022. 54 people killed by the Ugandan police during street protests in November 2020, including bystanders, were not included in the main data chart, in line with our criteria.

Zimbabwe: data from the Zimbabwe Peace Project (ZPP) covers politically-motivated intimidation, assault, kidnapping, arrest, detention, murder, arson and the withholding of food aid and other state services by state and state-sponsored actors (such as ruling party members). The ZPP also counted human rights violations committed by the opposition, but consistently estimated the percentage of these committed by state-sponsored actors at between 65 and 85 % of the total. Accordingly, we took 75% of the total reported numbers throughout. An increase in incidents in 2022 has been linked to upcoming elections in 2023. Six people killed by police during protests in 2018 were not counted, in line with our criteria. Concerning November and December 2022, we used monthly averages because ZPP reports for these two months were not yet available at the time of writing.

Kenya: data from Human Rights Watch and media reports include targeted election-related violence (both in 2017 and in 2022) against individual opponents and critics of dominant candidates as well as politically motivated intimidation, assault, kidnapping, arrest, detention, murder, arson by state actors and associated vigilantes.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Cry Freedom | Trends of repression and resistance in five African countries

Nigeria | Death by tax collector by Theophilus Abbah

Cameroon | The truth is a dangerous business by Chief Bisong Etahoben and Elizabeth BanyiTabi

Uganda | How to remove a dictator remotely by Emmanuel Mutaizibwa

Zimbabwe | No human rights for ‘bad apples’ by Brezh Malaba

Kenya | The hidden cost of free and fair by Ngina Kirori