How citizens once chased away as 'foreigners' came back with a vengeance

It was 2012 and we were to visit the places where the skulls and the bones would be, the witnesses of a massacre by ‘invading hordes’. The victims? Locals. The perpetrators were ‘foreigners’, the locals say. But things are not this simple in Ivory Coast.

‘I will show you the fields of death.’ And then, without fail, the offer was withdrawn: the people who were going to take me there never materialised. ‘How about going by myself?’ I asked the owner of the hotel where I was staying. ‘Out of the question,’ she told me, ‘they will kill you.’ ‘Who are “they”?’‘Dozos.’

Dozos are traditional hunters from the north, who arrived here as part of a rebel army, Forces Nouvelles. This army has joined the now official new military: the Forces Républicaines de la Côte d’Ivoire, FRCI. ‘You know what we call them? Forces Rebelles de la Côte d’Ivoire.’ My host spat with disdain when she described the people who had ransacked her business and destroyed a number of her stand-alone rooms, including the one next to where I was staying. Where were they from? ‘Outside. Burkina, Guinea, the North.’ The important thing to take away from this conversation was that, as far as my host was concerned, they didn’t belong here. And after what they did, she hated them all.

Tears in cocoa country

Duékoué sits in the heart of cocoa country: a warm, humid, lush and fertile land that the Ivorians call “Le Grand Ouest”: the Great West. You find the same land – and the same people – across the nearby borders of Guinea and Liberia. In and around Duékoué, the local Wê were in charge for centuries.

But that is not the case anymore. Under a canopy of mango trees, a gathering of chiefs explained to me that, even if they were OK with the present government administration by the new prefect, the locals still didn’t have their lands and their villages back. And the insecurity continued. “Even while there is talk of peace, people are getting killed here every day”, said Chief Guëi Joseph. “There are tears in many households. There are criminals about; we don’t know where they’re from. Some of our villages have been destroyed; the people are refugees. We ask the government to help bring everyone home.’ The session ended with the passing around of a heady local brew as the chiefs checked their mobile phones for missed calls.

A peacemaking tradition eroded

In the old days, the chiefs distributed land and settled disputes. This became more complicated during French colonization. The French encouraged migration around and into the country, especially into the Grand Ouest, where there were, as there are now, good rains, good soil and good money to be made from commercial agriculture. Côte d’Ivoire’s first post-independence president, the autocrat Félix Houphouët-Boigny continued the policy. Planters from the centre settled here; others from further afield were also encouraged to come. Among them a community called the Sénoufo-Malinké.

The latter community has been established here for a century, but is now seen by ‘locals’ as part of the ‘invaders’. Sénoufo-Malinké chief, Adama Dambele, told me that they, too, wanted peace. “We have lived here since 1910, but politics and the war have created divisions among us.’ The main problem, according to Dambele, was land ownership. “When our grandparents came here, the people who lived here accepted us and gave us a space. We had misunderstandings even before the war but we managed to understand each other and negotiate. But today, there are young people who come into the plantations that have been abandoned because of the war – and sell them to someone else.” The local grudges about this are added to the mistrust that affects this community.

Attacks against ‘those who are not from here’

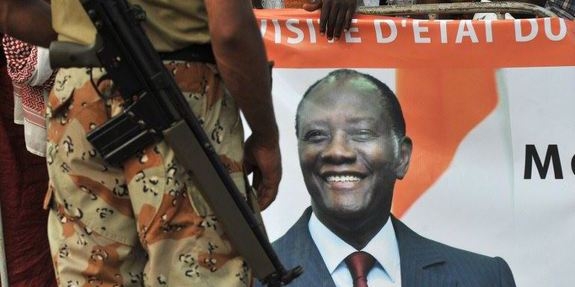

Did the war come before the divisions or the divisions before the war? It is difficult to say, but tensions, among which those between ‘locals’and those considered ‘foreigners’, emerged after the death of Houphouët-Boigny in 1993. His immediate successor built support on a new notion that hadn’t existed before:‘Ivoirité’. One was a real ‘Ivorian’, the doctrine went, if one had two parents born in Cote d’Ivoire. That excluded one-third of Ivorian citizens, including a high-flying presidential contender by the name of Alassane Ouattara. The struggles for political power and land rights then led to a first civil war, and then another president –Laurent Gbagbo- who adhered to the ‘Ivoirité’ concept. Gbagbo was the champion of the western Wê and ruled for a decade, until 2010.

When his challenger, Alassane Ouattara, a ‘not real’ Ivorian – like millions of people he can lay claim to at least two nationalities, Burkinabe and Ivorian - won the elections in that year, Gbagbo disputed the result and civil war started again. Militias, already set up by Gbagbo allies in his stronghold at the town of Guiglo, near Duekoue, conducted a reign of terror that lasted close to two years, carrying out attacks against people they considered “not from here” and killing political opponents until the end of the 2010-2011 civil war.

Ouattara’s rebel Forces Nouvelles, helped by the French and the UN, eventually won and were absorbed into Ivory Coasts new army. It is they who stand accused of the massacres at Duékoué. The old champion of the locals, Laurent Gbagbo is in jail in The Hague, awaiting trial.

Autochtones, allochtones, and allogènes

In 2012, one could sometimes believe the situation had returned to normal. Every morning, on a major crossroads in town, a man in white boubou and bonnet –definitely not local dress- set up his business: low table, simple wooden benches, small and efficient kitchen, French baguettes, Nescafé, canned sweet thick milk. Everyone appeared to mingle freely around the breakfast table of a man who could be readily identified as being Muslim and from the North.

But a very short ride away, 4000 people still lived in a camp for the displaced, called Nahibly.

It was in Nahibly that Yao Firmin, the young representative of the 4,000 inhabitants, took me around the makeshift tents, the schools, the football pitch. He explained how the divisions here still reigned: ‘You have three kinds of people here. They are, first of all, the autochtones, the original owners of the land. Then, you have the allochtones. Those are people who have come here from other parts of the country. And then you have the allogènes. They come from abroad.”

Yao would not blame ‘foreigners’ as a whole for the plight of the local refugees, but pointed out that the ones who took possession of the land of the displaced were ‘the people with arms’. “When they are in uniform they are the army; without uniform they are dozos. These dozos come from inside the country but also from Burkina, from Guinea, from Mali,” he explained. A fiery old lady by the name of Monsio Bertine confirmed: ‘Rebels and dozos are occupying my land in my village. I am afraid of them because they are armed. As long as they are there, I cannot go back and have nowhere to go but here. But the minute they leave, I’ll go back.’

In the end, Yao’s own young camp security militia, let alone the ineffective UN force of Moroccan soldiers that was actually supposed to guard the camp, could not save Nahibly. Three months after my visit, a dispute over an armed robbery in the ‘alien’ Sénoufo-Malinké part of town would spin out of control and the camp was burned down. At least 15 people were killed. It is claimed that Sénoufo-Malinké youth, dozos and even FRCI soldiers were involved. Today, I don’t know if Firmin and old madame Bertine are even alive.

Obstinate youth

On the other side of Duékoué, six kilometres down the road to the big town of Daloa, right next door to the local United Nations base, lay a village cut in half. Coming from Duékoué, the part to the left was in ruins, whilst the right part was alive and vibrant. Zouo Véronique lived in the destroyed part. ‘I was travelling when they came. When I came back I found everything gone and my relatives had fled. I sleep in my kitchen. Everyone else wants to come back too, but they cannot sleep anywhere. There’s not much we can do…’

The conversation took place mid-morning, in complete silence. Crossing the road, however, I was met by radios playing songs, children running around and people at work. In spite of the liveliness, the reception was extremely hostile. A half blind old chief appeared willing to talk but was overruled by an obstinate youth who said: ‘No interview will take place here.’ He added that he had ‘talked to many journalists but it has never brought me any benefits.’ The wall of resistance got stronger with every question.

The ruined half of the village was for the ‘autochtones’, the Wê; the noisy part belonged to foreign Burkinabe, said one local journalist. ‘They’re hiding something.’ Could it be that they were involved in destroying the homes of their neighbours? He and I had wanted to ask them about their relationship with Adama Ouérémi, a Burkina militia leader who had been illegally occupying land in a nature reserve nearby. Ouérémi, who was arrested in 2013, was almost certainly implicated in the Duékoué massacre. But no such luck. ‘They saw us coming from the other side,’ continued the journalist, ‘and had already decided that they were not going to talk to us. You know, you should never trust your neighbours when times are difficult…’

The crossroads where life ends

Just like in the village I had visited, a street ran through the middle of the town of Duékoué . The upper part of it was full of life, in party mode like only Ivorians can: good food, lots of drinks, music, merriness and beautiful people in that most Ivorian of institutions: the open air restaurant known as maquis. But at the crossroads, all life ended abruptly. Darkness and silence. No cars and certainly no taxis. Across the road: a hotel that served as temporary army headquarters for the FRCI and was also the place where I stayed. Since there was no transport after dark, I walked the two kilometres or so back to the hotel one night.

When she heard about it, the owner gave me a right earful: ‘Are you mad? That is the most dangerous street in Duékoué. People get killed there. Don’t ever walk there again.’ In fact, people get killed in and around this town every day. Crime? Banditry? Revenge? Politics? The answer was always the same: we don’t know.

A new building for the radio

There was some hope. Some young inhabitants of the area were working for reconciliation. The building of Radio Duékoué smelled of fresh paint and reverberated to the sound of hammers. Banhoue Maman Moh, one of the presenters, could not wait to get the station back on air again. ‘We invite everyone to come in and talk,’ she told me. ‘That’s our work: bringing people together. We also talk in every language, not just French. The fabric of this town has been broken but I think we can help restore it.’

I could only hope that she would succeed where the government’s ‘National Dialogue Truth and Reconciliation Committee’ was appallingly ineffective; the International Criminal Court’s investigation into the fields of death never ending, and the United Nations Mission had stumbled into irrelevance. But according to a January 2014 report by the International Crisis Group, almost three years after the massacres, very little has changed in Duékoué. Mistrust reigns supreme. The locals still want their champion back: Laurent Gbagbo, now imprisoned in The Hague; while those on Alassane Ouattara’s side have the unconcerned air of a winner.

Meanwhile, still, villages are empty; individuals are getting killed in the night and the pleas for peace from the old chiefs continue unnoticed.

Bram Posthumus (1959) is an independent journalist covering political, economic and cultural events in West Africa. He also writes on music and the arts. He works for radio, press and internet media in the UK, Germany and the `Netherlands. His book on Guinea will shortly be published by Hurst.