A transnational investigation by the African Investigative Publishing Collective

The mini-arms races of the Karamoja

Sitting on his three-legged stool at a watering point in Naput village in Moroto district, not too far from the Uganda-Kenya border, Moruita Lukotomoi says he once killed three men. “They had come to steal our cows, but we fought them and kept our cattle safe.”

That was in the early 1990s. But nowadays, after a period in which the Ugandan army disarmed the Karamojong cattle herding tribes, they can’t defend themselves anymore, he laments. “Bandits come to steal our donkeys and cows. Even now some of our donkeys are missing. Those people are able to steal our animals because we no longer have guns. If we had guns…,” he says, leaving the last sentence hanging.

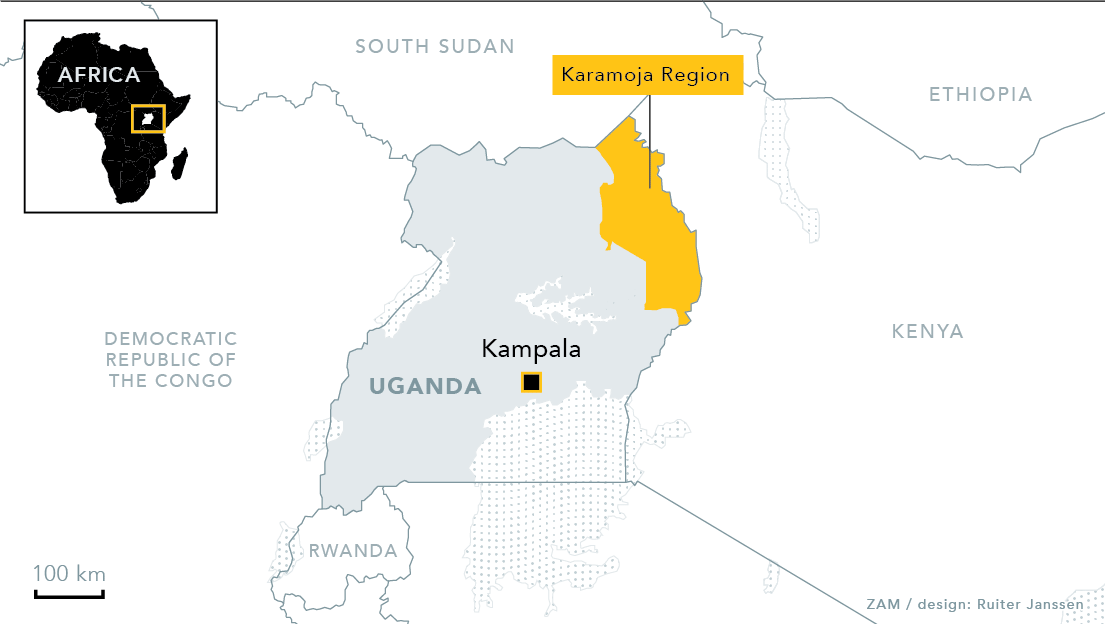

Karamoja is a semi-arid sub-region in the north-eastern apex of Uganda, with a population of 1.2 million people. It shares a border with Kenya to the east and South Sudan to the north, and regularly jostles for scarce water and pasture with nomadic pastoral groups from the two countries. For at least two decades, it has grappled with the proliferation of guns in the sub-region, in turn exacerbated by other armed conflicts such as in South Sudan.

According to various studies, the Karamojong first got their hands on guns in the late 1970s, during the overthrow of Uganda’s then president Idi Amin Dada by Ugandan exiles who were backed by the Tanzanian military.

A local council leader in Abim district, Richard Okori, confirms that the guns from that armoury provided the first weapons that the Karamojong used, either to raid others or to defend themselves. “It (the armoury) was left open and people carried the guns on donkeys the whole night. They could (now) ambush vehicles and waylay people.”

Eventually, the attacks spread to neighbouring tribes and even to communities in Kenya and South Sudan. Victimised communities also armed themselves, sparking off a mini-arms race.

In the early 2000s the government launched a military-backed operation to disarm all Karamojong warriors. Captain Isaac Oware, who is now the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) spokesperson for the army’s division in the north-eastern region, then a platoon commander, remembers: “The warriors were many and armed; the terrain was tough for us, and the climate was rough as well. They (the Karamojong) believed that guns and ammunition were part of their livelihood.” Oware narrates a particularly bruising battle in which the Karamojong engaged the military for an entire day. “We used Mamba and Buffalo armed vehicles [and] heavy guns. They were very many and were organised, with command elements and formations,” he said.

When the army eventually broke the back of the Karamojong resistance, the warriors called a truce and agreed to negotiations. The EPRC report says that in the negotiations, weapon holdings were reduced, but “on a varying scale:” “For instance, the Bokora sub-ethnic group willingly surrendered up to 44 per cent of their weapons, while the Jie and Dodoth respectively gave up only 27 percent and 20 per cent of their projected stock.” This, later observers said, created imbalances, whereby some groups still had arms and were raiding those who had been disarmed.

And then, the EPRC notes in its report, the whole exercise was shelved. That was because of the escalating conflict with Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army in the north of the country. The army’s move to the north “led to an increase in raids in Karamoja” again.

With a first -albeit rickety- truce signed between the Ugandan government and the LRA in 2006, disarmament exercises were again attempted in the Karamoja region. Initially unsuccessful, a “cordon-and-search military operation by the UPDF in 2008 finally netted 30,000 guns,” says the EPRC report. Today, according to Captain Oware, the army is conducting the “tail-end” of the exercise.

But he admits that the battle to pacify Karamoja is far from over, -and the fact that some groups now have arms and others don’t is part of the problem. “We still have areas of gun proliferation and firearms trafficking. Guns still cross the borders. Our borders are so porous.”

Perhaps inevitably, killings continue to occur. In February 2017, a group of Karamojong warriors killed three Turkana cattle keepers who had wandered in from Kenya. The Karamojong also took their victims’ cows, donkeys and at least a thousand goats.

Uganda was mortified. The army went out to confront the Karamojong, confiscated the stolen animals and duly returned these to the Turkana owners. The Ugandan government, intent on repairing relations with Kenya, then hosted a cross-border bilateral peace meeting on 2 March 2017. It was attended by a 50-member-strong delegation from Kenya, including the Governor of Turkana County, Josephat Koli Nanok, and several legislators.

At the occasion, Uganda’s minister for Karamoja affairs, John Byabagambi, apologised to the Kenyan delegation, saying that the Ugandans had killed their counterparts “for no reason.” The Turkana had been “peaceful,” he said. “They are in Uganda not because they want to be, but because it was forced on them by nature.” However, after Ugandan army delegates explained that often the Turkana enter Ugandan territory with guns, he added that the Kenyans should also disarm their herdsmen. “It should be obvious that to achieve peace and development, guns should not feature in the equation.”

Delegates did seem aware that cattle herding tribes are fighting for resources such as watering points and grazing lands. “The resources are (simply) not enough to support the cattle herders [in Kenya],” said Governor Nanok of Turkana County in an interview, but he seemed to state this merely to explain that the Turkana could not be blamed for needing guns. “(In absence of security provided by the government) people protect themselves and their livestock.”

Nanok and Byabagambi agreed that a comprehensive regional solution, which should include South Sudan and Ethiopia, was needed in order to make people less dependent on “expenditure (for their) defence.” Said Byabagambi: “We want to initiate regional projects like common schools and watering points along the borders so that these people, instead of moving deep inside other people’s countries, can (access these where they are.)”

Developing the warriors

David Pulkol, a former deputy minister for Karamoja and now the Executive Director of the Africa Leadership Institute, a policy think-tank on rural and border communities development based in Kampala, does not think much will come of such regional peace conferences. First of all, he says, national security is not a devolved function, adding that he has not “seen any national government involvement (in any) coordinated effort to see disarmament (in the countries of the region.”

Secondly, Pulkol doubts that the Karamoja warriors will change their ways as long as the only choice they have is between armed cattle herding and unemployment. “Even the security firms guarding NGOs in Karamoja bring their own guards from outside the region.” Rhetorically: “have you seen any economic programme targeting those disarmed warriors so that their heroism is harnessed? Are there any programmes targeting former warriors to move from destruction to development?”

Thirdly, he mentions the many injustices the people of the region experience. “There is a lot of looting, even involving government people. They run investment companies, grab people’s land and exploit the natural resources. [Foreign Affairs Minister Sam] Kutesa has shares in Tororo cement and the First Family [President Museveni’s family] has shares in Karamoja marble.”

President Museveni has often said he wants to create employment in marble mining in Karamoja, but Pulkol wonders how sincere such plans are. “You ask yourself why the state (seems) not interested in putting up weighbridges to ensure that we know how much limestone or marble is being taken out of Karamoja? (…) Museveni has co-opted our local leaders. As long as they are comfortable, they don’t care.”

For locals to really benefit from the emerging extractive industries, there should be resource sharing agreements, he says. “Even donors are advocating for alternative livelihoods, besides rearing cows and goats. Local people should be shareholders in the emerging industries so that they get dividends.” He believes a Marshall Plan, with “special scholarships to the Karamojong as a form of investment,” should be implemented in the region.

But all that is not happening. “I think the neglect (has been) deliberate. Our military officers are schooled, the ministers are well read and the president has a lot of experience. All these people could not have missed the dangers that the current situation presents. You can disarm (all you want) but if these injustices continue, then peace will not last. Should an opportunity arise, people who have hidden guns are likely to get them back. We are sitting on a time bomb.”

Efforts were made to get comments from the Ugandan government and presidency but none were received in time for the deadline.