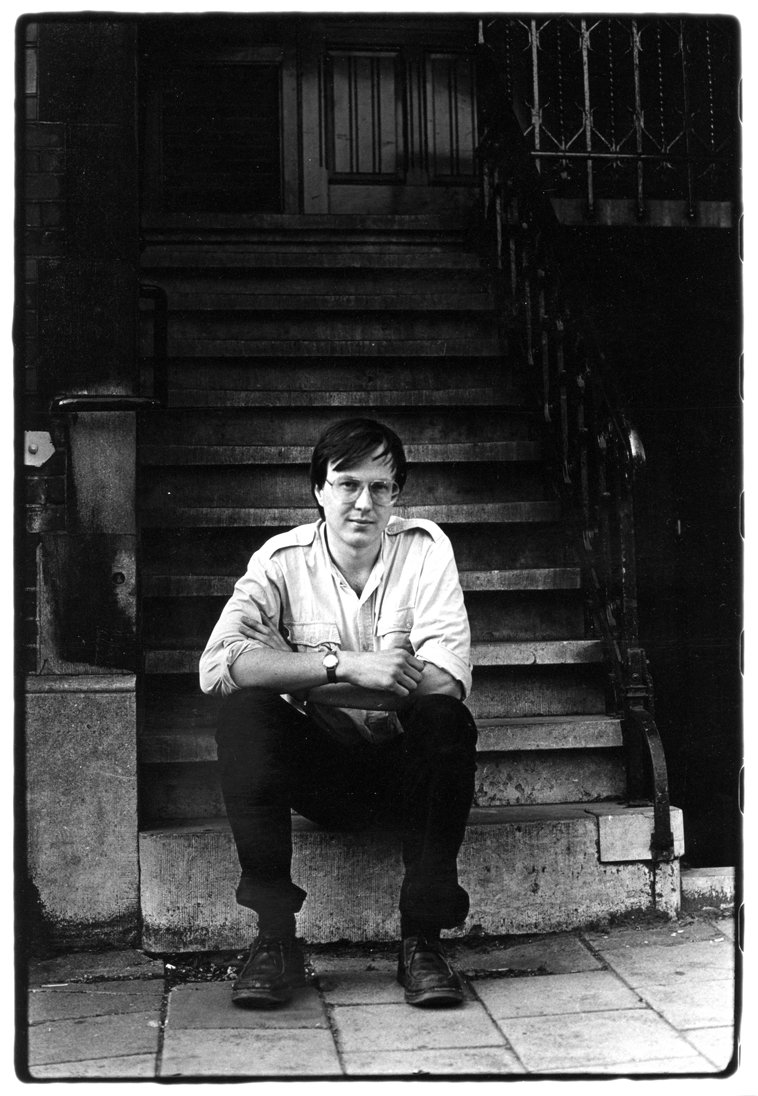

In this edition of ZAM Magazine we are publishing fragments from the unfinished manuscript Shadow Play by South African author Gerald Kraak, who passed away at the age of only 57 on 19 October 2014. This novel was to become the second volume of a trilogy, set in the years after 1976, when a new phase in suppression by and resistance against apartheid began.

Introduction

by Bart Luirink and Peter Sluiter

Gerald was born in 1956 in Johannesburg. He studied English, history, comparative African government, and law at the University of Cape Town. With many others of his politicised middle class lot, he became involved in student politics and campaigns against the role of the South African army in maintaining the apartheid system, the occupation of Namibia, and the undermining of independent neighbouring countries. This included supporting those who resisted army conscription and gradually broadened to more general anti-apartheid activity including illegal, partly ANC-related trade union involvement.

In the late 1970s, many young white activists like Gerald felt forced to seek refuge ‘overseas’, mostly in the UK. With some others, Gerald landed in the Netherlands, his father’s country of birth, where he fully remained the South African activist that he always was, earning a modest living by working as a documentarist and researcher for anti-apartheid organisations. He joined the Holland Committee on Southern Africa and the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement in Amsterdam. He then relocated to London as researcher for the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) and finally joined Interfund, which gave financial support to South African civil society organisations.

In Amsterdam and London, he helped to establish and run the Committee on South African War Resistance (COSAWR), which grew throughout the 1980s with sections in the UK and the Netherlands, encompassing a few hundred people. For many South African draft resisters and other exiles, he became the first point of European contact. By debriefing new arrivals, he remained informed of most recent developments, and in some cases managed to detect a few unsafe cases of people who were planted or blackmailed into cooperation by South African security forces. He shared his findings with his ANC ‘handler’ Aziz Pahad, who later became Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs in the first democratically elected SA government.

After political exiles could safely return to South Africa in the early 1990s, Gerald settled in Johannesburg where Interfund had also moved, and in 1994 he served as an election organiser in the first democratic, one-person-one-vote elections in the country.

In 1994, he joined the newly established South African branch of Atlantic Philanthropies as Programme Executive for its Reconciliation and Human Rights Programme, in which much attention was paid to gender issues. One of his main achievements was the support for legal action that forced President Mbeki’s government to provide antiretrovirals to people living with HIV, which saved millions of lives. Other issues that Gerald supported through Atlantic Philanthropies include former combatants, the establishment of the Constitutional Court, higher education, and health.

Aside from his professional activities, but very much in line with his personal convictions and commitments, he published writings about South African trade union activities before and after the (formal) abolition of apartheid, and about socio-economic development. He was involved in gay activism and directed the docudrama Property of the state: gay men in the apartheid military in 2003.

The books

The manuscript from which we now publish a short selection is the second in what was conceived to be a trilogy, inspired by but not literally replicating the lives of the author and those close to him. Individual lives may be recognised by those who have personally known the author, his friends, and his comrades. Others will read a true-to-life story about how these personal lives are intertwined with the struggle against apartheid, both inside South Africa and by exiles in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

The first book, Ice in the Lungs (Jacana Press, 2006), won the EU Literary Award (South Africa) and was widely praised as the coming-of-age story of a radicalising young white generation, having to make conflicting choices in politics and sexuality.

Shadow Play duplicates the epilogue of Ice in the Lungs, when Matthew, the main character, meets his friend Oliver, who had left South Africa before him. “So this is exile,” I thought. A crude word with its forbidding intimations of irredeemable separation, aloneness, angst.

Much of the book is very recognisably set in Amsterdam in the late 1970s, from which we have taken most of our selection of fragments, describing South African refugee life and activism with the milieu of radical left squatters and gay life.

Substantial other parts of the manuscript as a whole are set inside South Africa, focusing on the hidden lives of black and white activists, ‘’safe houses’’, illegal campaigning, and the like.

ZAM Magazine publishes these fragments both as a tribute to the author, one year after his passing, and as an invitation to read the whole book, which is currently edited for publication by Jacana Press, Johannesburg, and expected in the course of 2016.

A prepublication | Shadow Play

By Gerald Kraak

1

“So this is exile,” I thought. A crude word with its forbidding intimations of irredeemable separation, aloneness, angst.

I waited for Oliver at the bus station in Amsterdam.

My closest friend, he had secured political asylum as a deserter from the South African Defence Force, and was now enrolled at the Utrecht Conservatory where he was completing the violin studies that the army and our fevered Cape Town life had interrupted.

Oliver was late, and I stood in the melee of arriving passengers – nervous and disorientated amidst the fragments of foreign languages all around me. A flock of black sparrows circled above, throwing a sudden shadow from a lucid sky. They settled, shrilling, in the great trees that shaded the water in front of the station.

The branches of the trees and the mass of neglected bicycles chained in an asymmetry of spokes and skewed handlebars to the railing of a bridge were coated with their droppings, white in the sun, like petrified snow. I imagined that the droppings were ancient, that the accumulated sediment was testimony to countless generations of sparrows whose daily wheeling marked the changing history of the city.

I had taken the discounted Luxavia flight from Johannesburg to Luxembourg, and dozed intermittently on the bus to Amsterdam. Waking in Gouda, I had looked out of the window and encountered the curious sight of white workers laying sewage pipes in freshly-dug ditches alongside the road. This was my first sleepily-comprehended intimation of life in a society where race did not determine every social interaction.

2

“Do you miss South Africa?” Oliver asked. The question startled me from my reverie. Why had he asked that question, now, after a month in Amsterdam? Perhaps this afternoon when we had dropped into the Bruna bookshop on the Leidsestraat on our way home, he had noticed my browsing of the small foreign-language section at the back, seeking out new titles from Africa. But that had less to do with homesickness than finding something to read that I could understand. Or was I out of touch with my emotions, Oliver divining something unplumbed from my couch-bound listlessness?

Had I stayed, I would now be in an army uniform illegally invading Angola or in jail

“Not especially,” I answered. “It’s a relief to have left. Anyhow, had I stayed, I would now be in an army uniform illegally invading Angola, or in jail for refusing to serve. Few options. I couldn’t do what you did, Oliver. I couldn’t run, hide, like you. I don’t have the same mettle as you.”

He did not answer. I heard him strike up a match to light a cigarette.

“I love this city now, or at least I think I do,” I said. “I love the calm, the lack of fear.”

I looked down at the retreating swan.

“And you?” I asked one.

“What?” Oliver replied. Confused.

“South Africa,” I responded.

“I hate the place!” he said with vehemence. “I will never go back. It is brutal! Europe is my home.”

I did not want to argue with him. We were different people – I was dismayed by Oliver’s short exile’s lack of rootedness and alienation, whereas I could identify through my activism; my country kept tugging me. But we shared enough for friendship.

“Let’s leave it there, Ol,” I said. I sighed and knocked back another jenever. Oliver noticed. He turned up Maria Callas. I smiled at him. He came over to me with his glass of red wine and sank into the couch. I lay against him and then allowed my head to sink into his lap. He ran his fingers through my hair. I closed my eyes and listened to the Callas.

3

There was an anti-apartheid movement in the Netherlands. One afternoon I encountered a demonstration – a surprisingly large group – on Dam Square. They held a banner: Van Agt’s beleid, lafaard’s beleid. Sancties tegen het Zuid-Afrikaanse moordregime nu! (“Van Agt’s policy is a coward’s policy. Sanctions against the murderous South African regime now!”).

Suddenly, here was some evidence of my homeland, and my heart lurched. I took a leaflet from one of the demonstrators – from my limited grasp of the Dutch, it seemed concerned with some lapse of Dutch foreign policy on South Africa that amounted to appeasement of the apartheid regime. It pilloried the Dutch Prime Minster.

The crowd began chanting, their animation and noise disturbing the pigeons on the square, ascending now in an untidy dark flurry, circling over the cobbles in several loops and finding refuge on the slate-grey tiles of the Nieuwe Kerk, a tall graceful cathedral which loomed over the northern edge of the Dam.

Here, I might have encountered a kindred spirit or at least discussed South Africa, had some news of home. Instead, I was intimidated by them. There was something studied, liturgical about out the chanting – even. It seemed to lack emotion, a more primal identification withheld, I felt.

“Hun strijd onze strijd, internationale solidariteit” (“Your struggle is our struggle. International solidarity!”).

And, indeed, as I later became part of the city’s political life, attending demonstrations in solidarity with third world struggles, many of the same activists were there, chanting the same slogans with the same studied duty.

The same activists were there, chanting the same slogans with the same studied duty

At the back of the demonstration was the banner of the FNV trade union federation and, indeed, in the ranks of protesters were some men – workers in the charcoal overalls of stevedores, from the black cold-water docks to the north. But most younger people – the counter culture of the mid 1970s had lingered in Amsterdam – were long-haired, dressed in the ubiquitous jeans of the time, baggy jumpers or shapeless anoraks, and sheltering in Palestinian keffiyahs for warmth, heavy Doc Martens for shoes. Some had a seemingly deliberately-constructed bulky scruffiness – a badge of provocative unkemptness.

An image floated up in front of me of the street protest in Cape Town the year before, during the uprisings of 1976. I saw and heard the struggle songs, the deep resonance of the male bass undertow, the ululation of the women above, the emotional tug of the song echoing between the buildings, Senzenina, Senzenina. And the way the youths had danced, taunting the police lines, gesticulating at the yapping bare-fanged Alsatians, taut on their leashes, a choreography of courage. It was beautiful.

This noisy demonstration, here on the Dam, was ugly. I felt no heart to it. I was seized by a pang of emotion – a longing for home.

4

Gradually my depression waned. After the rain, the clouds lifted above Amsterdam and the greyness of the streets receded, the distilled spring sunshine drawing from the red brickwork, a pale ochre glow. Opposite the entrance to the Vondelpark, off Leidseplein, crocuses appeared, a motley spread of white and intensely yellow flowers, and the sharpness of the light belied the chill which still beset the city. As we shopped among the stalls of olives, pickles and Mediterranean vegetables – yellow lemons and ruby tomatoes stacked high – our breaths steamed in front of us. In Oliver this was endearing. I would have liked to have kissed him then, so the trails of our vapours entwined, but it was too public a place, Turkish women in hijabs embroidered in reds and golds, flashing with sequins, trailing shopping carts, and gruff moustachioed fishermen holding up sleek, writhing eels for sale.

Oliver was my new certitude and an unaccustomed domesticity settled over me. Until now, I had lived in a kind of benign squalor, allowing books and papers to pile in corners, sleeping in the same sheets for weeks, wearing the same clothes for two, three days at a time. Oliver was too busy to cook and clean, treating the apartment as a crash-pad between his dawn trips to Utrecht, sleeping through the weekends to recoup energy and avoid the cold streets.

I recognised that in my depression I had become dishevelled, and now I was reclaiming sartorial space trying to bring back the dapper, aesthetic student I had imagined I had been in Cape Town.

5

I saw her across the concourse in the cavernous, echoing space of Centraal Station – a melee of floating, disconnected voices – the only constant being pre-recorded messages about the train traffic. She was standing at the information kiosk, unchanged, it seemed from this distance – dressed with care and poise, dated amidst the studied dishevelment, except that she was winding her long hair through her fingers, a sign, I knew from those days, of past anxiety. In one hand she clasped a briefcase, beside her a small compacted haversack. I strode across the concourse and was within a few feet of her when she caught my gaze – recognition instantaneous. I fell into her arms. She drew me into a hug, its strength in its requiredness. When I looked up at her there were tears streaming down her face. She tried to brush them aside, then gave up and fell against me. “It has been so hard! I have missed you.”

Resolve resumed, she pulled away from me, blinking fiercely. “You look good, so clean-cut and fiercely handsome! Exile has been good for you.”

“No madness like at home,” I responded lamely. For she looked worn-out, now that I was close to her – a dry brittleness to her skin, a dark blush under her eyes, a fatigue it seemed that had crept under her skin and stayed there. “Christ,” she said. “I need a drink. Take me to a bar!”

6

“You aren’t missing anything,” she said. “South Africa is a land of ash.” She described the life of the last three years. After the arrests of Paul, Themba and Luke, she had gone to ground, her role in the underground activity by which we were consumed, undiscovered. She resumed her studies, avoiding her activist connections the police and army had crushed after the uprising. They had incarcerated its leaders and outlawed the organisations the resistance had spawned. An arid normality returned.

Gradually she re-surfaced. When she completed her degree, she moved up to Johannesburg and was doing her articles in a progressive law firm, working with poor clients – the usual cases. Unfair dismissals, evictions, police assaults, torture while detained. “Ever the activist. Nothing has changed,” I sighed.

“Things have to change,” she said wryly. And then a change of tenor. She cast a glance around her, as if something malign might be lingering in the neatly pruned topiary of the park. Yet about us a benign sociability continued – sunbathers on the verdant lawns of the park, the distant pulse of a jazz concert on the lake, pensioners sipping coffee over the dailies. She leaned in over her whisky, her voice dropping.

“Matt – what I have to tell you must remain between us.” I nodded, leaning closer too.

“A small group of us have got together: unionists, student leaders, some movement stalwarts – we have formed a cell, we are meeting regularly now. And we are linking up with the movement – the exiled ANC, to see how we can revive their structures in the Johannesburg area. I am going to London to make contact with the ANC. That’s why I am here. I, we need you to be part of it.”

7

It was early evening. The bar was quite full, frequented by dark hued Surinamese, only a few white faces in the throng. I recognised him from Pru’s description. Mandla was sitting at the back of the bar, sunk back in a sofa, a beer on the café table in front of him, facing the door, sheltering behind a copy of The Guardian. He was sharp featured, almost leonine, and his cheeks were lightly scarified, part of his youthful initiation. He was as dapper as Pru had described, dressed formally in a charcoal suit, a crisp white shirt, but no tie. There was an ebony sheen to his skin where the collar, unbuttoned, opened his throat and a tautness to the physique that filled out his jacket as he stood to shake my hand – a firmness to his grip. My nervousness abated.

He was matter of fact about my recruitment into the ANC

He was matter of fact about my recruitment into the ANC. “Trusted comrades” had vouched for me, but before we next met I was to draft a detailed autobiography, so that his structures could finally vet me against their information. He told me that the Movement was regrouping inside South Africa, after the repression of the 1976 uprising. They were gathering intelligence, building new networks, seeking strategically-placed recruits. Europe – cities like London and Amsterdam – were ideal places to have “listening posts”. South Africans passed through as tourists, participants on the conference circuit, to study perhaps. These cities with their thronging crowds, their anonymity, were perfect places for the Movement to gather information, to meet with activists from inside. People like myself – not openly identified with the Movement – were perfect go-betweens. The ANC, he said, would use me to do research, to debrief people passing through, and to pass on messages and tasks both ways. This information would be absorbed into the larger structures of the ANC and help rebuild the underground. He smiled; “You are nervous,” he said. “Is this too much technical detail?”

8

Though we were in the “underground”, engaged in clandestine operations for the ANC, the fear of discovery and arrest a constant undercurrent to our lives, these were halcyon days – a disaster. At first, I was unnerved by my necessary proximity to Rachel. White people were strangers for me. Training in the Soviet Union, our instructors had of course been white, but their authority was conferred by rank, not by race, and they were boldly internationalist in their outlook, given to camaraderie in the military mess halls after a day’s training, dispensing shots of vodka. We had had nuns as teachers when young – but they were Irish. White South Africans were a different species, encountered in my youth as the police whom we feared or the odd shopkeeper in the local township supply stores who patronised us. There was never genuine connection. The ANC was avowedly non-racial; we knew that in the capitals of Europe there were communities of exiled white radicals, draft dodgers and others involved in campaigns to ‘isolate the apartheid regime’ – but in real terms one rarely encountered whites in the camps in Africa and even then only senior leaders of the movement, political commissars, communists from another age. The foot-soldiers were black.

And so I was initially anxious around Rachel, my palms clammy in her presence, reticent at first in my conversation, expecting from here some slight or racist rebuke. I slept in a room at the back of the house – the servant’s quarters, they were called, so that there would be no hint of impropriety should someone call unexpectedly or see me about the house. It was a comfortable enough room – the racial hierarchy implied by my presence, no offence.

Our growing familiarity grew out of necessity. We needed to discuss and agree upon our mission. In her house with its many shelves of books, I discovered a synergy of literary tastes: South African fiction and history, biographies of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky, histories of the French resistance and the Spanish civil war, the novels of Dostoyevsky and the English classics. In the evenings she played Coltrane, Miles Davis, Count Basie – the strains of jazz filing the house – music I remembered from the turn tables in the dormitories when I had studied at Fort Hare, as we sipped whiskies, watching from our eyrie as the sun set over Helderstroom at dusk. The breeze rustled in the pines and the metallic rhythm of cow bells rang out in the valley below as the herd-boys shepherded cattle across the shores of the lake.

9

Mauritz and I were good for each other. I was engaged by the otherness of him, this doe-eyed gazelle of a youth let loose in the streets of Amsterdam, profoundly damaged, intriguing. He was equally intrigued by my exile status – my reports from another front. He was incredulous at my experience, at my stories about South Africa – he would get animated and enraged. How could this be in the 20th century?

Mostly though he was a soulmate. Our lives worked well together. My intelligence work, his forays into the radicalism of the squatter movement. Clandestine worlds. Secrecy. We were both bred to it. None of Oliver’s cloying possessiveness. No drama. A loose commitment.

So days might go by without connecting. When we did it would be in a late bar – cold beers, jenevertjes, vodka with orange juice. Then, inebriated, our skins tingling for each other, we’d go to my room, have ecstatic sex, and then the next morning some aspect of domesticity, coffee and a toast ham and egg uitsmijter from a working class café near the station, or simply weak black tea – Dutch style – and toast in my bed.

I loved him for this ease, this simple flow of our time.

He had studied art at school and told me he painted – though I had never seen any of his work. In cafés and bars he’d draw me caricatures of the patrons – effete, preening boys comparing clothes – robust working class women, downing beer – an aging man with his dog – a likeness of him. They were witty, clever – I pasted them to my bedroom wall.

We had our differences though. Mauritz did not hate classical music as such, but associated it with the violent regime of his childhood home – the Sunday afternoons, parents by the radio listening to some classical repertoire, followed by an arbitrary beating for some slight against his father. He could not countenance it. He allowed me my solitary attendance at the Concertgebouw to hear some exquisite rendition of Dvorak’s folk dances. I’d sit there in the stalls, taken up by the music, but there’d be the tug – an undertow – the absence of Oliver. I’d come away from the concerts, a sadness at the edges of my consciousness.

10

Mandla was not impressed by my recounting of the skirmishes around Herengracht 51. In fact he was suddenly angry – an emotion I had not yet encountered in him.

“M. has told me about this,” he said. “Are you a complete amateur?” he admonished me. “Do you want to compromise your refugee status? Do you want to compromise this – our work?” He pointed to the papers spread out on the table in front of us. We were meeting in the Paramaribo and he had treated us to mojito each.

“Matthew,” he said, “This is an anarchist movement, using violence against a democratic state.”

I interrupted him, cowed. “Only one strand of it is anarchist,” I said. “It is a broad-based movement.”

“But the anarchists set the tone. Don’t you think that it is under surveillance by Dutch intelligence? They are watched. You will be watched too.”

The image of the exploding petrol bomb came into my mind, and of the plain clothes stillen who had emerged from the crowd of shoppers to snatch a squatter leader and bundle him into car.

He went on. “We don’t want you to be the subject of interest by the Dutch; it is enough of a problem staying off the radar of South African security.”

“What should I do? I am a squatter, after all. I am bound to support the actions of the movement. I owe it to them – that I have a place to live.” I said nothing about my passion for Mauritz, my erotically idealised activist.

“I know, I know,” Mandla replied. He was well versed in the shortage of accommodation in Amsterdam – and London for that matter. He had described his small room behind Kings Cross to me. “We need to find you a respectable abode.” His tone was ironic. The anger had gone.

“Let’s order another mojito and deal with your report on South Africa; god forbid there is no anarchist trend there!”

11

England smelled of tar, a tincture of coal smoke on the air as I arrived at Liverpool Street Station. I had spent a sleepless night on the ferry from Hoek van Holland to Harwich. The vessel was crowded, the lounge taken up by passengers, some trying to sleep wrapped in sleeping bags on the floor between the café tables. They included a large group of Swedish teenagers – members of some sporting team, intent on drinking the night away. The lounge, windows sealed against the icy spray of the sea, was close, a fug of cigarette smoke and the sickly sweet scent of the press of bodies on the air.

About Gerald Vincent Kraak

Born in Johannesburg, 29 November 1956

Secondary school: Westerford High School, Cape Town

University of Cape Town: English, History, Comparative Government & Law, Social Anthropology and African Economic History, 1975 - 1978

NUSAS – National Union of South African Students, project / research officer, 1978

Left South Africa for The Netherlands, June 1979, worked as documentarist, researcher with Holland Committee on Southern Africa (KZA – HCSA), then with Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands (AABN)

Resettled in London, 1984, worked with the International Defense and Aid Fund (IDAF) as documentarist, researcher, then from 1989 with Interfund as grant maker, project manager

Returned to South Africa - Johannesburg in 1992, continued working with Interfund, from 1995 joined The Atlantic Philanthropies as Programme Executive for its Reconciliation & Human Rights Programme.

Passed away: 19 October, 2014, Johannesburg

Read more about ZAM here and more Chronicle articles here. The Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA) archives have a collection of items about Gerald Kraak. Check out their website.