Africa, Africans art exhibit in Brazil evokes slave trade, sugar cane liquor, missionary zeal and voodoo

For the past eleven years, the wooden carcass of an old ship has sat in the central hall of São Paulo’s Afro-Brazil Museum. Imposing in its proportions and haunting in its decay, it has stood as the institution’s most commanding testament to the history of the transatlantic slave trade since the doors to the museum were opened in 2004.

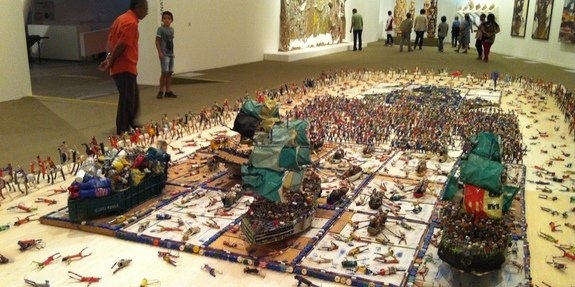

But since May 24, this ship has been replaced by different vessels. In its place today is a sprawling installation titled Stupides et inutiles (‘Stupid and useless’) by Beninese artist Aston, in which five model ships glide across the floor, green sails in the air and decks overflowing with people who fall into the surrounding waters. At the far end of the installation sits the silhouette of the African continent: a reminder of where these ships, like the one that usually sits in their place, came from.

Aston’s chilling installation is the centrepiece of Africa, Africans, the Afro-Brazil Museum’s new exhibition devoted to contemporary art from the motherland across the Atlantic. Bringing together one hundred works by twenty artists either hailing from or based in Africa, it is the largest exhibition of contemporary African art ever to have been organized in Brazil.

Cynically playful

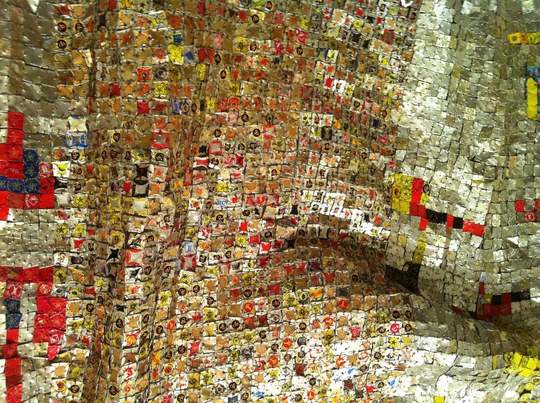

The curators were clearly thinking big when they planned the show: the artists are some of the most renowned on the African art circuit, and the works on display are mostly large in scale and striking in style. Flanking Stupides et inutiles is one of El Anatsui’s signature panels, Skylines, a voluptuous sheet of metallic liquor bottle caps that cascades from ceiling to floor with the exquisite elegance that characterizes the Ghanaian master’s creations. It too alludes to the history of trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas: sugar cane liquor was one of the principal commodities brought from the New World to the Old. Given new form, fluidity and grace here, at the artist’s hand, the bottle caps remind the viewer that histories too can move, change and transform.

‘Egg fight’ satirises old conflicts between Protestants and Catholics

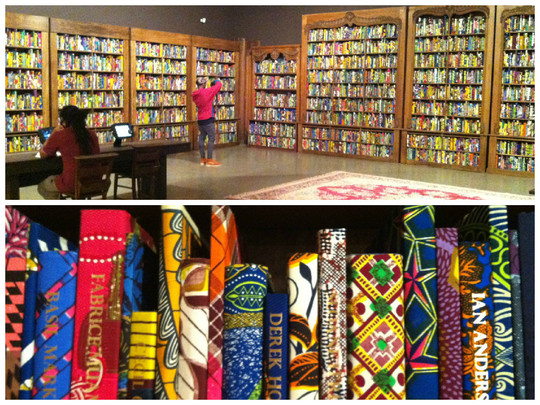

In the gallery above, two installations by Yinka Shonibare MBE are instantly recognizable for the prominent appearance of the artist’s favourite materials: multi-coloured African wax-print textiles. The first piece, the cynically playful Egg Fight, has two headless mannequins, each dressed in 18th-century riding coats made of African fabrics, aiming rifles at one another from across a wall made of chicken eggs. Alluding to a scene from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels in which two characters argue over which end of a boiled egg should be broken first, the piece is a satirical take on the centuries-old conflicts between Protestants and Catholics.

Walking past this absurd scene, the viewer enters Shonibare’s British Library. The installation has all the fixtures of a reading chamber from the historic institution – wood-panelled walls, tall bookshelves, dim lighting – with one exception: the books on the shelves are bound in covers made of the same colourful, wax-print fabrics. The names on the spines all have at least two things in common: all are well-known and all belong to authors who immigrated to the UK. Viewers are thus compelled to reflect on the ways in which the histories of colonialism, cultural imperialism and migration have shaped Western societies.

Acid rain

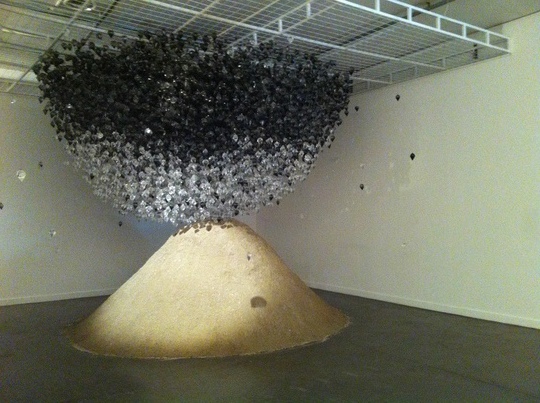

Artists Bright Ugochukwu-Eke and Dominique Zinkpè are behind two of the exhibit’s most remarkable pieces. Ugochukwu-Eke’s Clouds, Earth, Twist is a mesmerising meditation on the dramatic ecological disasters facing our planet. In a dimly-lit corner of the upstairs gallery, hundreds of small, darkened plastic bags filled with water tumble from the ceiling onto a heap of brown sand, evoking the showers of acid rain that fall every day upon the artist’s native Nigeria and locales the world over.

In an equally dramatic piece, Dominique Zinkpè guides the viewer through a dark room filled with miniature wooden statuettes, which hang from the ceiling by the hundreds. Old flip-flops are scattered across the floor and sit in a heap at the far end of the room. Above, a video streams on a projection screen, alternating between a close-up of a hand scribbling names on flip-flops and shots of a Black Christ hanging from a cross. The installation’s dreamy title belies its force: Parfum d’existenceis a disturbing statement on the history of missionary activity in Africa, the clash between voodoo spirituality and Christian doctrine, and the deep connections between modern consumerism and religion.

Wire sculptures evoke the fragility of existence

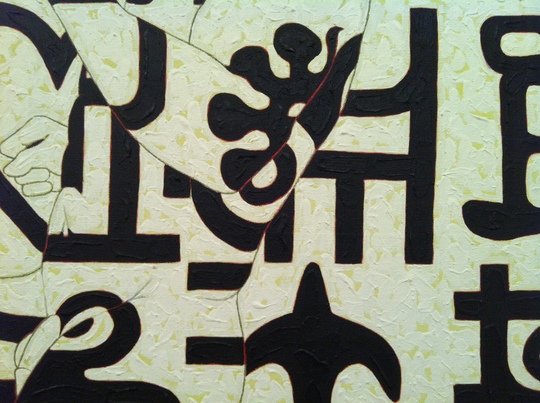

Although photography and video are regrettably absent from the exhibition halls, the show does not lack in memorable paintings and sculptures. In a particularly striking room, Ablade Glover’s vivacious semi-abstract paintings of market scenes in Accra hang beside panels from Owusu Ankomah’s Cosmocon series, in which the silhouettes of warriors dance across backgrounds of black-and-white Adinkra symbols. In the corner, Remy Samuz’s intricate wire sculptures of anonymous standing figures echo the metaphysical questions raised in the paintings: of man’s place in the cosmos, the fragility of existence, the instability of the boundary between the physical and the spiritual world.

No explanation

These themes emerge in spite of the total absence of explanatory text from the walls of the exhibition. There is no introductory text at the entrance, nor are there panels beside any of the works. Only the press release gives some guidance as to the show’s objectives: Africa, Africans is intended first and foremost to offer a “panorama of contemporary creation in Africa.”

In that sense, one assumes that the curators aimed to introduce the Brazilian public to the continent’s tremendous creative output without constraining interpretations of what Africa or African art might be. It seems, then, that their method was simply to assemble as many dazzling works as possible and let them do the talking for themselves.

It becomes easy to understand why the curators wanted to make such a splash when considering the history of exhibitions of African art in Brazil – or rather, the lack thereof. The exhibition is not just the largest show of contemporary African art ever to have been shown in Brazil, it is one of the first. Besides a handful of other “survey”-type shows in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia in the last five years, the country’s institutions have largely left contemporary African art outside of the purview of their exhibition programmes.

Racismo cordial

This lack of representations of contemporary Africa in Brazil’s cultural institutions is consistent with a deeper and more problematic pattern. The vast majority of Brazilians have notoriously little knowledge about their African heritage and even less about contemporary Africa. Decried by activists, scholars and artists for decades, this troubling state of affairs persists in spite of the deep historical connections that link their country to Africa and which have shaped it into what it is today.

Brazilians have notoriously little knowledge about their African heritage

Brazil was the largest destination for African slaves: even the most conservative accounts estimate that between four and five million Africans were brought to the country’s shores between the year of the first Portuguese settlement, 1501, and the end of the slave trade in 1888 (Brazil was the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery). Today, Brazil is home to the largest population of African descent outside Africa: among the world’s nation-states, only Nigeria is home to more Africans than Brazil.

A long history of racism in Brazil’s institutions and in popular culture – what Brazilians call racismo cordial, or “cordial racism” – is to blame for the ignorance of African histories and cultures that runs rampant in the nation. In popular culture, portrayals of Brazil’s African heritage are typically reduced to mystified versions of capoeira (the system of movement, blending martial arts and dance, that was originally developed by slaves as a form of revolt and self-defense) and candomblé (the religion derived from a fusion of Iorubá and Fon religions, Indigenous belief systems and Catholicism). Samba and carnival also have roots in resistance culture, having emerged as the expressions of pride, joy and emancipation of the formerly enslaved. However, both were so thoroughly appropriated as symbols of a unified, Rainbow-nation-style brasilidade (“brazilian-ness”) over the course of the 20th century that these roots have largely been erased from official speech and common knowledge.

Africa and African cultures have thus been made exotic in a country that was built on the labour of African slaves and whose fantastical cultural makeup would not be what it is without the varied forms of creative expression brought from across the ocean.

Afro-Brazilian perspective

Against this cultural landscape, Africa, Africans does come as an important initiative. It is no surprise that it should be the Afro-Brazil Museum that hosts it: it is one of the key institutional players in the effort to change perceptions around Brazil’s African heritage. Founded in 2004 on the initiative of artist and collector Emanoel Araujo, the museum aims to tell an “alternative Brazilian history” from a specifically Afro-Brazilian perspective – a mission which it fulfils remarkably. Blending history, anthropology and art, the museum showcases a dizzyingly rich collection of objects and artworks that together address diverse facets Afro-Brazilian life: labour and slavery, religion and spirituality, sport and leisure, art and craft. The museum’s sprawling dimensions and its location in the centre of Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo’s largest and most popular public green space, also give it significant power and reach. (Issues of accessibility were clearly a priority for the organizers of Africa, Africans, for that matter, as the museum has waived its entrance fee for all visitors for the duration of the exhibition.)

Africa, Africans fits into the Afro-Brazil Museum’s recent efforts to shift to a more “transatlantic” perspective. This push was initiated in 2011 with Elos da Lusofonia (“Lusophone Connections”), a show that attempted to highlight the centuries of cultural exchange between Brazilian artists and their Lusophone colleagues across the Atlantic, in Angola, Mozambique and Cabo Verde. It has been followed up with an exhibit on Fela Kuti in 2012 and another on symbolic objects from Porto-Novo, Benin in 2014.

Given this orientation, one wishes that the curators had gone to more pains precisely to make the transatlantic connections that the exhibition calls for. In many ways, Aston’s Stupides et inutiles is left to bear the responsibility of connecting Africa and Africans to Brazil and Brazilians. Indeed, with no text on the walls to assist the viewer in making links between the other works of Africa, Africans and those by Afro-Brazilians in the galleries above, the exhibition runs the risk of upholding many prevailing notions of Africa: as a big place, bursting with power and creativity, but still different from and outside of Brazil.

Deep ties in brilliant diversity

But to focus on the positive: in their brilliant diversity, their finesse and their force, the works of Africa, Africans are sure to leave an imprint on many memories far past the exhibition’s closing on August 30. Moreover, one hopes that the exhibit can be a move toward more open recognition of and deeper investigation into the deep ties that link the two continents and their peoples – not just at the Afro-Brazil Museum, but in the country’s institutions at large. Although they have their roots in a horrific past, these transatlantic connections have evolved over the centuries and continue to morph as new trade routes, migration patterns, communication technologies and cultural pathways emerge. It is high time they be recognized, unpacked, questioned, celebrated.

Lara Bourdin is a writer, researcher, editor and translator. Trained in European and African art history, philosophy and postcolonial theory, she is currently pursuing new research projects on Afro-Brazilian art, the arts of the Lusophone world and transatlantic cultural exchange. All photographs are taken by Lara.