A white journalist goes out to investigate Ebola in Sierra Leone

Travelling on an airplane never failed to amaze her. Well, only if she managed to get a seat by the window, which she did on the Brussels Airways Airbus A330. Anja Brink’s curiosity surpassed that of a hawk; that bird of prey that detects its victim from afar and then dives to catch it. She carried the same deep eyes but hers were blue as the sky.

As she watched the approach to Lungi from the window of the airplane, she saw school children scatter across a field as they ran to their homes. Thatched houses with mud bricks, corrugated aluminium roofs and small ponds lying as remnants from the spill of the Atlantic Ocean few weeks ago. On the peripheries of the green lay immense savannah and huge and long trees, all standing in harmony and appraisal of the scorching red sun. Farmers in the fields bowed to weed, harvest or plant crops. A few cows in the fields wandered amidst an abundance of food. “A land of plenty,” she thought.

A few cows in the fields wandered amidst an abundance of food

As the plane prepared for landing, it banked hard and glided between the sea and the huge mountains surrounding Freetown, the capital city of Sierra Leone. The passengers became uneasy as the plane wallowed down in aggravating turbulence. Anja tossed back her half-finished whisky to keep it from spilling and turned around to watch the faces of the passengers. Coffees spilled, luggage jostled and nerves rattled. An elderly African couple sitting next to her roused from half-slumber, tightened their seatbelts and then held hands with eyes closed, murmuring prayers for a safe landing. Other passengers did the same. Some remained strapped to their seats and held their breath.

As a seasoned journalist, Anja had travelled extensively from war-torn Afghanistan to Syria and Iraq, from earthquake-ridden Haiti to Turkey and Bangladesh, even covering the disasters wrought by tornados in the USA and poverty in Latin America. You name it. She was always there. Flight was common. From her perspective, turbulence was an inconvenience, not a safety concern. She understood that when a flight changes altitude, it is in search of smoother conditions, by and large in the interest of comfort. It was in travelling by air, though, that she had come to embrace death as inevitable, an event that could come at any unexpected moment. In fact, she had made a list of death wishes. She thought dying in a plane crash or by gunshot was what a real death should look like, with life vanishing like a vapour. Deaths, she thought, should be fast, sudden and free of suffering.

Deaths, she thought, should be fast, sudden and free of suffering

While her thoughts wandered, her mind suddenly diverted paths and she lost her daydream. Her deep blue eyes started focusing on the faces of the passengers again and again, like a lens bringing far-away objects closer. They intrigued her. They were similar to the ones she had seen on airplanes travelling to and from Asia or Latin America. They were faces of people who were not prepared to die; all prayed to the spirit of life to guide the pilot to safe landing.

As if their prayers had helped, the pilot was able to land the plane without a problem, even though the front wheel coming down heavily made the passengers draw their breaths sharply. There was a collective exhale as the plane rolled to a halt. They jubilated and clapped hands to the glory of the Lord. They had made it safely to Sierra Leone.

An African couple

It was in that euphoria that the elderly man seated close to her gave her a hand and congratulated her.

“For what?” she asked.

“We made it,” he laughed. Then asked her: “What is the purpose of your visit, business or pleasure?”

“I am coming to stick my nose into a business that….”

His wife was listening to their conversation. Her eyes were bulgy and her round chubby face expressed defensiveness. She did not await Anja’s answer.

“Are you one of those foreign investors who believe that Africa is for all?”

‘Oh, may I guess? Are you one of those foreign investors who believe that Africa is for all? That we do not know what to do with our mineral resources? Or are you one of those missionaries who has come to save us from our heathen ways?’ she asked in a hushed tone of voice.

“Not at all. I am a journalist,” Anja answered.

“And then what is that business you mention?” the wife of the elderly man continued

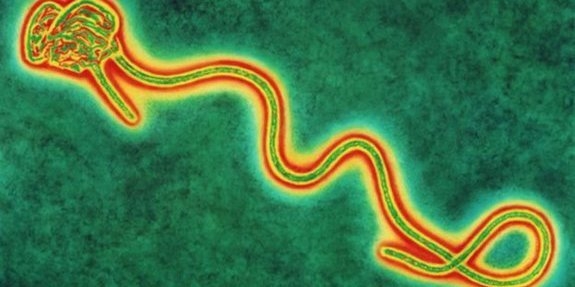

“I am here to investigate the mysterious Ebola virus that has surfaced in the East of the country.”

“Oh, the East, that’s where we are from. And we are victims. That virus has killed almost our entire community,” the man said. Anja tried to catch a glimpse of grief on his face but all she could see was a man who was self-contained, matter-of-fact, and could express little outward emotion.

“I’m sorry to hear that. It is terrible and terrifying,”Anja said.

“I heard the USA has a treatment for it but it is only meant for white people,” the wife said. Again her voice was low as if suspicious of the life she might give to her words.

“I have no idea about that,”Anja responded in the same diminished tone of voice.

The few times the elderly woman had met white people, she had found them irritating. She felt irritation again now. They pretended not to know how privileged they were and wanted to be best pals with you, but at the same time they didn’t take you seriously and behaved like know-it-alls. This white woman was now mimicking her tone of voice, as if mocking her.

The few times the elderly woman had met white people, she had found them irritating

Instead of saying anything further she withdrew her huge body and kissed her own teeth. It was not a sign of truce and Anja grasped that, but she wondered what she had said that had so irritated the elderly woman. While she pondered, the flight crew announced: “For your safety and comfort, please remain seated with your seat belt fastened until the plane has come to a complete stop.” Anja looked out of the window again and saw an aging building painted white with a huge sign-board stating ‘Welcome to Lungi International Airport.’ The plane headed towards the building and slowed to a stop.

Metamorphosis

After the plane was parked Anja loosened her seatbelt and stood up and twisted her long blond hair into a bun. She rearranged her flowing yellow dress, covering her extra-big bust and noticeably round tummy. Despite the dress, one could tell that she had solid thighs and a well-formed round butt.

Anja noticed after standing up that most people gazed at her for a bit and briefly wondered if that was because she was white. Then everybody got on with the job of disembarking. While some passengers, tired of the long journey, started to stretch and contort like catapults, others were struggling to get their luggage from the racks above.

The elderly couple were standing, ready to disembark. An hour before the plane landed they had already gone to the toilet to refresh. When they had returned to their seats they had metamorphosed. Anja hardly recognised them. They had changed their clothes and now wore white linen suits with hats. They smelled of expensive perfumes, probably Chanel.

They now wore white linen suits with hats and smelled of expensive perfumes

‘You both look gorgeous’, Anja had complimented them as they took their seat.

‘Thank you’, the elderly woman said. The husband, too, showed appreciation at the compliment.

‘Are you heading to a festivity after disembarking?’, Anja had asked with almost childish curiosity.

‘No, it is just a habit to look good after coming from the States. That is what our people expect of us. A bit crazy to stick to this routine at my age’, the man had said.

The hostess had interrupted their conversation by serving them tea and coffee. Anja took coffee black and both the man and his wife had tea with milk and a lot of sugar. After that there had been no exchange of words until the plane landed.

Now that they all stood waiting to disembark, there was the awkwardness of saying goodbye to new acquaintances. Anja turned to the man and said: “I wish you a safe journey to Kailahun.”

“The same to you. If you don’t mind, you can join us, we have a jeep waiting to take us there.” His wife gave him a jab, not amused that her husband was paying so much attention to Anja. Speaking to her husband in Mende, whispering in a tone calculated to provoke his anger: “You are engaging with her as if she is a type of trophy.”

“You better behave yourself, woman,” the man sneered back, raising one corner of his upper lip.

All this happened out of Anja’s hearing but she noticed that it was about her and put it down to jealousy. But it wasn’t that. The woman, still irritated, was simply protecting her husband from a white girl who was, in her opinion, acting like she deserved a medal for taking the time out to come save poor Africans.

“You can join us if you want,” the man said again to Anja.

“No thanks. Dr. Koroma has sent a driver to come and pick me up.”

“Oh, the renowned Dr. Koroma? He is our hero. The only doctor who ventures in to our villages to save lives.”

“I am really sorry to hear about the circumstances in Kailahun,” Anja said.

“It’s OK. It is destiny and we only can pray for those gone to enter the gate of heaven.” He smiled, waving his hands as if the virus he was talking about was just one of the many natural hazards that came, stayed and were gone.

They had learned that mixing stoicism with humour helped to rise above tragedy

Having been spared because they had gone on vacation to the States at the right time, the couple did not want to wallow in Anja’s sympathy. Over the years, they had learned that mixing stoicism with a sense of humour was sufficient to rise above even the darkest of tragedies.

The moment they set foot outside the plane, to greet the land of their birth, the elderly man and his wife bent their bodies to kiss the ground. ‘This is the land that we love’, they said in chorus, as if they had rehearsed for several hours before performing this rite. Anja watched with amazement.

Being a just-come

When they got up they walked towards the hall for arriving passengers. Anja walked side by side with them as they entered the wide open door leading to the arrival hall. They walked pass dozens of people scattered around like sculptures; local men and women in civilian clothes. All they did was gaze at the ‘JCs’: those that had “just come”.

Many ‘JC’ had towels on their necks. In their hands they carried long rubber bottles filled with mineral water. People gazed at them because they were seen as pushy, loud, impolite, unruly. And they were everywhere. Although the locals welcomed them and their valued foreign currency, they loathed the chaos and hassle the ‘JCs’ brought upon their towns and cities.

Anja, who was ignorant of this, wondered what the source of their fascination really was. When she entered the arrival hall she was enveloped in heat. She assumed the air conditioning was either off or not working at all.

Within fifteen minutes the humidity had drenched her in sweat

Within fifteen minutes the humidity had drenched her in sweat. Her thin silk dress clung to her body, and the contours of her big bust and round butt now became a wide source of fascination. The mouths of the men who stared at her dripped words of admiration like awi! ayi ahoe! and eeeyi! Her soaked clothes left little to their imagination. It was not what they had expected of a white girl. Solid thighs and a well-formed round butt were assets they only attributed to black women.

While the men continued staring, the women picked and chopped her with their eyes and mouth. They jealously castigated her in their minds for exposing her body to the hungry eyes of perverse men. Anja caught yet more words thrown at her; O’Kuru Masebah! Astafulahi! and O’Gaywoh! These too were words of exclamation but not admiration: they asked God to forgive her for tempting their men to sin more.

Anja was tormented by the scene, felt oppressed by the chaos and staring people, and nearly choked on the thick hot air. Her body reacted as a stranger to her. “Africa is a pilgrimage,” she thought. A friend had told her that Sierra Leone was not an African country for beginners. It was still a country without good roads, with poor Internet communication and an equally poor healthcare system. “Ghana is an easier place to start experiencing Africa,” she had been told.

Man live by man

While she leaned with her back against a pillar trying to figure out where to go, her attention turned to the dozens of people who were not passengers but who continued to roam and stare. By now it seemed to her that Sierra Leone was a land of ever-waiting, wide-eyed individuals.

One of them suddenly approached her, giving Anja a form to fill in. ‘It is for immigration’, the man said. While Anja fumbled in her handbag searching for a pen, the young man offered to fill in the form for her. ‘I can do it myself, thank you’, she said smiling politely.

She wondered how they could maintain a firm grasp in this mess that seemed like an absolute zoo

The arrivals hall was already crammed with people scrambling and sending the airport in to a scene of confusion. In an attempt to reduce tension two police officers tried to restore order by hauling passengers in to the right queue. Anja realised she had lost sight of the couple from the plane. She wondered how they could maintain a firm grasp in this mess that seemed to her like an absolute zoo. Then she suddenly saw them standing close to her, flanked by another young man who busily filled in their forms. The elderly man, who had noticed Anja’s exchange with the voluntary immigration assistant, explained the situation to her. ‘We could do it ourselves but these young men are searching for work. Man live by man’.

Anja, not convinced, faked a smile and then concentrated on filling in the form. After the blanks on their form found answers of name, age, marital status, job, home address and motive of visit, the elderly couple handed ten dollars to the young man. He jumped in the air with excitement, then thanked them gracefully, asking God to protect them and provide plenty for them.

Anja shook her head in disagreement. Whilst preparing for this journey, she had read that one should not give money to beggars and not hand over bribes to corrupt civil servants. In her mind she had started to feel –but would not dare say it aloud- that this poverty stricken country would remain on it knees. “Just ten dollars made this young, able, man jump sky-high,” she thought. “Suppose it was a thousand dollars? Would he kill a human being for such an amount?”

Moiwo

When Anja finished filling in her form she joined the queue of passengers with foreign passports. Around twenty Chinese men stood in front of her. One after the other, the Chinese men had their passports quickly signed and stamped. It seemed their origin was enough to avoid further interrogation. “Africa’s new kids on the block,” she thought.

She then turned to her left to search for the elderly couple. They stood at the back of a longer queue meant for African passport holders. The man smiled and waved when he caught her glimpse. Anja waved back quickly, then turned her face away again.

He was a tiny man wearing a blue police uniform and a cap that seemed to wear his head rather than the other way around

It was her turn to hand over her passport to the immigration officer seated in a small wooden kiosk. He was a tiny man wearing a blue police uniform and a cap that seemed to wear his head rather than the other way round. On his breast-pocket was his name, embroidered in bold letters; MOIWO.

“Good day sir,” Anja greeted him pleasantly. She gave him her passport and form.

The officer took the passport but refused to answer her greetings.

“What is the purpose of visit?” he asked without raising his head. He spoke with hostility and Anja wondered why he was being cranky at her. Did she do something to piss him off? Or was he just too lazy to read? He was studying the passport by turning the pages randomly.

“I am a journalist,” Anja answered.

“Who invited you to our country?” he asked with a furious tone in his voice, still his head bent down as if he was a laboratory assistant looking through a lens.

“Please read the form. I have filled in all the necessary information, mister,”Anja said softly.

This caused the officer to raise his head up and look right into her eyes.

‘I ask the questions and you give the answers, do you understand?’

Anja was again surprised at the anger in the officer’s eyes. His tone of his voice was sarcastic and insincere. But most of all it was his accent that intrigued her, as if he was a graduate from Cambridge University speaking the tongue of the Queen of England. His eyes were red and tiny and his teeth were yellow at the bottom, near the gums. “I know you have filled in the form but that is not my question.”

Suddenly Anja could not utter a word. She blushed with embarrassment; her neck went pink and her whole face red. A volcano in her was about to erupt, but her clenched teeth tightened the door to her troubling emotions. Her eyes went wide and staring, not very different from all the people around her.

The man was clearly an imbecile who had never heard of deodorant

‘The man has the manner of a pig’, she thought while her lips refused to allow the words to escape. “And he smells like one too.” She had tried to ban the smell of the man from her mind at first, not wanting to think a black person ‘stinky’ –but god almighty, the man stank! Then she admitted the thought. The man was clearly an imbecile who had never heard of deodorant.

If this was in The Netherlands Anja would have told this insolent man off. She could even have taken him to court for misusing his position as a civil servant. But this was her first trip to Africa and she had been warned about the differing values when it comes to the rights of private citizens and authorities; the place of a woman and a man in society and the wide gap between the rich and the poor.

The officer was still looking at her with a question on his face.

“Let me reiterate: who invited you to my country?”

Finally she spoke: “I am commissioned by the World Health Organization to report on the mysterious virus that is killing your people in the jungle in the Kailahun District.”

‘Aha, you call my home town a jungle?’ the officer asked. He almost got up from his seat.

“Sorry for using that language,” Anja quickly apologised.

‘I wish you a pleasant stay in the jungle and hope you will write the truth about a virus you white people brought to our people.’

The rude, smelly idiot thought that white people had brought the Ebola virus

Again she did not know what to say. White people brought the Ebola virus? This rude, smelly idiot with the Queen’s English accent thought white people had done this? Whilst she had specifically come to help, at no little risk to her own life? “Stinky, rude and racist,” she thought, with tears welling up. This time, involuntarily, the words came out, albeit in a whisper.

“What did you say?”

“Nothing sir,” she answered politely.

The officer stamped her passport and gave it to her. He avoided looking her in the face.

“Next person,” he ordered.

A lighter outside

Anja walked towards the luggage carousel where passengers and helpers stood waiting to pick up their belongings. She could not stop thinking of the way she had been treated by the immigration officer.

“How come this man doesn’t seem to like people who come to help?” she wondered. “Is he an exception? Or do they generally not welcome help? Do they not recognise our good intentions?”

When she arrived at the carousel she noticed her flashy red Samsonite, the envy of the rest of the bags on the belt. She quickly picked it up, raised the handle and started wheeling it to the exit. A local old man approached her with a tired stride, his face dried up as if he was starving.

A local old man approached her with a tired stride, his face dried up as if he was starving

‘Madam, please allow me to help you with your luggage’, he said weakly.

Anja refused, shaking her head and walked past him with her angry face, insistently independent. Her confused state of mind after the confrontation with the immigration officer had still not cleared.

‘Man live by man’, the old man said after her. His voice took on an undeniable harsh, hostile edge.

She ignored him.

The sun was shining and those waiting outside, in contrast to the people inside, seemed happy

As she came out of the arrival hall, her anger subsided immediately. She stopped thinking about the humiliation and abuses the immigration officer had thrown at her. The sun was shining and those waiting outside, in contrast to the people inside, seemed happy. These were faces genuinely grateful to receive their love ones.

It made her feel lighter.

She noticed that one of the happy faces belonged to a man holding a white paper above his head with her name misspelt in bold letters: ANGA BRINK.

She walked to him returning his smile. The man walked forward to meet her, ‘My name is Vandy, Dr. Koroma sent me to pick you up.’

‘Good day Vandy, so you are ready to take me straight into the centre of the storm?’ Anja said earnestly while extending her hand to greet him.

Vandy refused to shake her hand

Vandy refused to shake her hand. Instead he bowed his head slightly to the ground. Anja was startled but thought the man might have a reason for doing so.

“Perhaps it is against his religion or tradition to shake the hand of a lady,” she pondered.

Vandy saw Anja’s face falling like –as he compared in his mind- a sensitive mimosa plant. He thought he should explain himself.

“Since the outbreak of Ebola, Dr. Koroma has told us to avoid handshaking and hugs.”

‘Ah, now I understand’, Anja said with relief, thinking she had acted stupidly. After all, she had come to report on Ebola: she should know better. She could kick herself for not immediately getting the point.

Instead of rolling the suitcase on the ground he raised it on his head

Vandy took her luggage from her. Instead of rolling it on the ground he raised it on his head. Anja walked behind him to the direction where the private vehicle of the World Health Organization was parked. Vandy opened the back door of the white jeep and lowered the luggage from his head in to the boot. He then closed the door and gestured to Anja to take the front seat. And off they drove into the crooked dusty road that was, Anja imagined, like the body of a coiled snake, with its head buried in the heart of the storm. “I have come to follow the path of a snake,” she thought, suddenly.

A local car ride

On their way to Kailahun they saw people walking in the middle of the road; men with cutlasses and hoes, women bearing on their heads baskets full of fruits and vegetables. Three young children walked naked beside them. As the van approached the pedestrians, the driver honked, and the blaring sound of the horn made them squirrel away to the side of the road. Vandy, the driver, did not slow down but accelerated as he passed them, beating the horn repeatedly like a crazy pianist. The van left behind a yellowish cloud that rose to the sky like sprinkled gold dust. As he sped pass them, a greyish black smoke oozed from the tailpipe of the van. The three children sprinted to catch up with them. As they got nearer, Vandy added speed and the children were lost in the cloud of black smoke. They stopped and started laughing.

The van left behind a yellowish cloud that rose to the sky like sprinkled gold dust

Vandy noticed Anja’s face, twisted in disapproval. He knew why and he wanted to put sand over it. “The people in this part of the country don’t fear machines,” he said defensively. They were his first words to Anja after leaving the airport in a fashion she considered to be reckless driving.

“But there is no need for you to drive like… that, right?” Anja wanted to use the pig word but then she thought otherwise. That word was reserved for Moiwo, the officer who humiliated her at the airport. She tried not to think of him. But Vandy’s bad driving had just added salt to injury.

In her many years of travelling abroad, Anja had come to know a simple way to understand the face of a country: through the behaviours of its police officers and taxi drivers. She struggled not to judge too quickly, but she could not avoid her mind turning Moiwo and Vandy into true ambassadors of Sierra Leone.

‘There are lots of accidents in this part of the country. People in this region fear cows more than motorists,” Vandy continued in a further attempt to break the tension.

Anja wanted to respond but was distracted by the sight of a bridge that seemed impossible to cross. She wondered how Vandy, with his reckless driving style, would cross over. She shifted around in her seat and held tightly to the handle above her head as the van bumped in to potholes that filled the road. She turned and looked at Vandy and saw his jaws moving like a ruminating goat. ‘I hope he is not on drugs, for God’s sake’, she wondered. She contemplated taking the steering over from him. Then rejected that thought, knowing that, even if given that opportunity, she would refuse. This was not her world.

Monkey bridge

“Please take your time here,” Anja pleaded. She knew that was all she could do. “It is a normal monkey bridge,” came the answer. “I have learnt to cross over them since I was twelve.”

“You mean you started driving when you were twelve years old?”

“Exactly. My father is a lorry driver and he taught me to drive.” Vandy considered telling Anja that at that age of twelve he was the most trusted adjutant and driver of a renowned rebel commander called General Mosquito, but was afraid Anja might start to see him differently. Just like Dr. Koroma who had come to distrust him when he learnt that he was at one time a fearless child soldier. “Everything comes to pass except the past,” Dr Koroma had said to him. Though the war ended more than ten years ago, its scars still marked the face of the country and its people.

Though the war ended more than ten years ago, its scars still marked the face of the country and its people

“At age twelve you could already drive. Wow! It seems everything is possible in this part of the world,” Anja remarked.

“Well, almost everything,” he said as he looked at her with a smile.

It seemed Vandy had appeased her. She was now calm as they approached the bridge.

“God willing we will be having a new bridge in a year or two or three. The Chinese are already working on a new road,” Vandy said as he pointed in the direction where huge machines and caterpillars were parked, surrounded by crushed stones, sand and gravel.

She took her head out of the window to look at the direction Vandy was pointing. “Has the work started?” she asked. “Not yet, but the presence of those machines with the heaps of crushed stones and sand gives us hope that something is about to be done,” he said and continued with a tone of scornful scepticism: “Dae pa dae wok.”

“What does that mean,” Anja asked.

He cackled. “Oh, that’s Krio, our lingua franca and it means our president is at work.”

“It’s not a joke, right?”Anja asked, puzzled.

“No, at all not,” he laughed. It seemed like he wanted to criticise the president, but did not dare to do so.

It seemed like he wanted to criticise the president, but did not dare to do so

Anja wanted to tell him that twenty Chinese men had already arrived with her today but she could not be sure whether they had come for the roads.

Vandy moved the van carefully towards the wooden bridge made from two trunks laid horizontally apart from each other.

“You are going to drive over like a rope-walker,” she said trying to make a joke. Vandy was too busy to notice. He twisted his mouth as if he was going to blow a whistle and his eyes focused on the bridge ahead of him. Anja had never seen a bridge like this before. She held tightly to the handle on the door. After Vandy brought the front wheels onto the tree trunk, he then drove the van slowly across. Anja glanced out of the window and saw a small river underneath with women and children standing by the water’s edge, washing clothes and cleaning their cooking utensils. On seeing Anja, the villagers shouted opoto; meaning ‘white man’ -in her case, white woman.

A while later, the opoto became pumui. They had travelled from North-West to South-East, from Temne to Mende land. The demographics as well as the tongue of the people had changed.

The safety of reckless driving

Remarkably, the behaviour had changed somewhat too. Anja noticed that when the pedestrians in the South-East saw their van coming, they ran in to the bushes. They stayed there until their van passed and then came out hesitantly.

Anja felt the need to comment, even if she would risk offending Vandy. His driving had endangered them both as well as many pedestrians they had encountered.

‘These people are sensible’, she said. ‘They don’t trust machines driven by men like you, who have no respect for the rules of the road. I would do the same if I was them’.

If not because of his dependency on this driving job for his living, if not because Anja was a woman and a white stranger, Vandy was ready to stop the vehicle right away and let her march out. He had done that before to two locals he had given a lift. Instead of being thankful the men were telling him how to drive with care. He had stopped in the middle of the road and in the middle of nowhere, and had forced the two men to vacate his vehicle.

He detested the arrogant way Anja had spoken to him, but would not say anything to annoy her

But Anja was Dr Koroma’s white visitor and not a local. In as much he detested the arrogant way Anja had spoken to him, he would not dare to say anything that would annoy her.

‘I have never travelled to your part of the world but I am quite sure that adopting your western style of safe driving in my country could be suicidal’, he said instead.

‘How can safe driving be suicidal?’ Anja asked.

‘Well, talking about your western style of safe driving means you first have safe roads, safe vehicles, honest traffic wardens and law abiding citizens. If these pedestrians know that I cannot drive over them, they will never leave the road for me to pass freely. So what I am doing is making them believe I am ready to kill anyone who is standing in my way. This is what I do, and this is what everyone does. So welcome to Sierra Leone, the country without the infrastructure for proper behaviour. It is a bit like our democracy. Western style in form, but without the basics.’

Anja had difficulty understanding this explanation. Her mind was in turmoil. Surely everybody should just get educated about road safety, proper behaviour and democratic habits? Then again, maybe they couldn’t help it, she argued with herself. The country lacked good schools. There hadn’t even been car traffic for that long. The culture was still one of walking.

But clearly, Vandy was not just an ordinary driver and definitely not an ordinary fool.

“How long have you been driving for Dr Koroma, Vandy?’” she asked.

“Just a year, when I could not find a suitable job after finishing my university education.”

“What did you study, if I may ask.”

“Political Science and Sociology.”

“Good to know that.”

Vandy was an academic? Anja felt that her adventure into the strange jungle of Africa had now started for real. She should not have apologised to Moiwo, she thought then, for calling this place a jungle. In her opinion, it was. “Perhaps he wanted me to call this place ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘little Amsterdam’,” she murmured to herself.

“What did you say,” Vandy asked. “Nothing,” Anja answered, quickly, as if suddenly waking from a deep slumber. She was unpleasantly surprised that the thoughts that had inflated inside her had escaped out in to the air. She did not want Vandy to know how she was starting to feel about his country.

Kola nuts and photographs

The van slithered up muddy banks that were overgrown with elephant grass on either side. Anja held tightly to the handle on the side of the door to keep her balance. The road was full of holes and rocks that made the van move with caution. Anja curled her back into a slight stoop. She noticed wheel marks another van had left behind and thought of the elderly couple, but figured it was impossible for them to be in front -unless their driver was even more careless than Vandy.

Vandy turned to her with a smile that showed his red gums. It made her wonder what he was chewing that made his mouth look like a volcano. Again he seemed to know what she was thinking. “In science, it is called ‘Garcinia Kola’. It is used in my culture for both traditional and medicinal purposes. It is helping me against contracting this Ebola virus. You can try it if you want to.”

‘No, thank you.’

His jaws moved while he chewed the brown, nut-like seed.

‘Was it a prescription from Dr Koroma?’ Anja asked with curiosity.

‘Dr Koroma is against its use’, he answered.

‘But then, why are you sure this ‘Kola’ will protect you against Ebola?’

“Let me tell you something. Our traditional healers have confirmed that it works. So in the absence of actual medicines, we have no choice but to listen to those in our community who know the secrets of the bush.”

Not wanting to argue, Anja nodded. “If a university graduate like Vandy can turn to herbalists for medicines, what can be said of those who never went to school,” she pondered. She then turned her face to look outside as the van slowly drove past the green vegetation and hills capped by huge trees.

Anja saw monkeys wiggling and moving around trees to get at the various branches.

The monkeys walked behind their leader who was carrying a stick

She asked Vandy to stop. Not knowing the reason for her request, but complying nevertheless, Vandy stepped on the brake. Anja fumbled in her bag looking for her camera, found it, took it out and pressed the ‘on’ button.

The monkeys had left the trees after the van came to a stop. They now walked behind their leader who was dragging a stick behind him. Two dozen of them were walking towards them. Anja took picture after picture. Vandy drew a sharp breath.

“We should leave this place immediately. Dr. Koroma said that these monkeys are carriers of the Ebola virus,” he said.

Anja did not take him seriously. Surely, one only got infected from monkey meat, if one ate it, and not just from looking at the animals? “Just a few more pictures, please.” She continued taking photographs of the monkeys.

The engine of the van was still on and its humming sound seemed to amaze the monkeys as they came to surround the vehicle. They made weird sounds and some of them, especially the young ones, were performing like circus acrobats by twisting their bodies into unusual positions. Some of them jumped and sat on the bonnet; some others jumped on and off the roof of the van.

“Let’s go now, it is getting dark and there really is mortal danger here.” Vandy was restless and his fingers on the steering were shaking like a Parkinson patient.

The monkeys seemed to be enjoying lounging around the van until their leader got bored and started hitting the van with the stick in his hand. Vandy reacted immediately by pressing hard on the horn to scare them away. They dispersed in disorderly haste.

They continued their journey to Kailahun. Anja went through the pictures she had taken and deleted those she thought were not good enough. Vandy put a CD into the player and then took out another bitter kola, which he had kept wrapped in a bundle of green leaves. He bit it off with a cracking sound and started chewing.

The beat of the song that was playing was made by an instrument Anja did not recognise. It was a horn that made a blaring sound like the horn of the van. A male voice blasted, echoing a thick voice like a rocker. Anja moved her head with the beats of the song.

‘African music, for some reason, gives me so much hope, even though I may not know what they’re saying’, she said.

‘The song is about good winning over evil’, Vandy said.

‘I hope that the evil Ebola is defeated as soon as possible’, Anja replied, still nodding to the beat like –Vandy thought- a snake head.

‘May the Lord hear you. Amen.’

While they drove past villages they saw no humans

While they drove past villages, they saw no humans. Only dogs, chickens, sheep, goats and more monkeys seemed to be wandering about. “Fear of the virus has driven people away from their villages into bigger towns and cities,” Vandy explained.

There seemed to be nothing to say after that.

The head of the snake

In front of them was another broken road piled with red gravel. It seemed as if the road was about to be repaired but the workmen had suddenly stopped in the middle of construction. “A low car that ventures on this road will regret why it was ever made in the first place’, Vandy said as he brought the van to a sudden stop.”

In front of them was a stream of water running; the bridge that once stood there had disappeared.

Vandy seemed glad that the night had not fallen completely. Anja ventured a joke. “This road is just made for the Paris-Dakar rally,” she laughed. But Vandy clearly had no idea what a Paris-Dakar rally was. He was silent, and Anja decided not to distract him any further as he figured out a way to cross the pond of brownish water.

Vandy clearly had no idea what a Paris-Dakar rally was

It was clear why four-wheel drive vehicles were the masters of the roads here. Vandy slowly descended the van into the pond. The huge tyres disappeared into the murky brown. Vandy accelerated, the tyres spun, and the van made a tiring sound before it moved forward and ascended a small hill that led to the dried road. After eight hours of driving, they were now approaching their destination.

The sun was fading and the clouds foaming in the sky. Anja looked out of the window and saw a beautiful wall of forest green, broken only by tiny red flowers, orange cocoa leaves and sudden clearings of rice paddies. Against the backdrop of this beauty were destroyed buildings and burned houses. “Those burnt houses are the scary faces of the brutal conflict we experienced,” Vandy said, noticing that Anja was looking with curiosity. Anja had read about the civil war in this country. “I guess the world still sees Sierra Leone as a country in turmoil,” she ventured.

“Not any longer,” Vandy responded. “Now we are known as Ebola land.”

“Please tell me more about Kailahun. Its people. Their way of life. Are they nice people?” Anja asked then.

“Yes, we are terribly nice,” came the answer. “We are so very nice that the people in the North-West call us the ‘educated fools’.”

“Really? Do they call you that?”

“The ethnic group from the North-West see us from the South-East as people who love education and respect for the laws of the land.”

“And what about the people in the North-West? Don’t they love education? Don’t they respect the laws of the land?”

“A few of them do,” he laughed and continued: “They are mostly petty traders, but more or less in a socialist manner.”

“What do you mean?”

“They rule the country like a business mafia. They prefer to share profits among themselves rather than allow one of them to grow and surpass the others. If you do that they will bring you down. Because they are in the majority in our country, their way of life has dominated the way outsiders like you think of us.”

“Most of my knowledge about this country comes from the Lonely Planet Travel Guide,” she laughed. “Besides a bit of history, that is. For the rest the guides only mention the beautiful beaches, the lovely people, the religious tolerance and the many mineral resources.”

“Our door seems to be the entry point of all evil. First rebels, now the deadly virus”

“That too is true,” Vandy said, and continued: “But despite all that we remain one of the poorest countries in the world, ruled by the president and his cronies from the North-West as a kind of unsuccessful socialist cooperative.”

“Ah, what a sound analysis,” laughed Anja. “Is that also how they would describe themselves? Or is it just how you from the South-East perceive them?”

“Well, it is how we see them, but it is also true,” he answered.

“And how do these people from the North-West look at you, who are you from the South-East?’”

“To them, we are just chaos. Our door seems to be the entry point of all evil into the country. Starting with the rebels and now the deadly virus.”

Anja nodded again. She felt she was learning something, but wasn’t sure what. It seemed as if Ebola had something to do with the social, political and economic structures that underpinned the very system this virus had come to destroy. Was the virus a lens through which one could and should look at people’s behaviour and thinking?

As they were approaching the head of the snake, Anja wondered whether it had poisonous teeth.

She remembered how Moiwo had blamed white people for Ebola. How the elderly woman on the plane had believed that the USA was producing medicines against Ebola that ‘cured only white people’. And now Vandy said that the north-West was blaming the south-East for the very same Ebola.

As they made their way through the woods leading to Kailahun, complete darkness fell over the land. As they were approaching the head of the snake, Anja wondered whether it had poisonous teeth.

Babah Tarawally is a writer and journalist. He is a columnist for OneWorld online magazine. After fleeing Sierra Leone civil war for the Netherlands 19 years ago and spending the first seven of those years filing an asylum application, Babah Tarawally began working for independent media outlets in Africa, contributing stories and columns to several newspapers and magazines. Alongside this work, he worked for Free Voice (now called Free Press Unlimited), a Dutch organization that support press freedom in Africa, Asia and Latin America. He worked for Free Voice from 2004-2010 as the project officer for Africa. In 2011 he worked as the Program Coordinator for Winternachten-Writers Unlimited Festival, Dutch biggest international literature festival. His novel 'De god met de blauwe ogen'(The blue eye god) was published in 2010 by KIT publishers. Babah Tarawally is presently working as a freelance journalist and on his second novel 'The missing Hand.'