His art was there, but artist Sammy Baloji was missing at an otherwise spectacular exhibit in London.

A travelling case full of fake diamond-studded watches, paintings of city life in Abidjan, masks made of petrol cans and West African textiles bearing the silhouettes of ‘missing’ girls, were part of a spectacular selection of contemporary art at the art fair held in London’s Somerset House. The impressive event was only marred by the absence of Congolese photographer Sammy Baloji, who had not been given a visa, though his photographs were part of the exhibit.

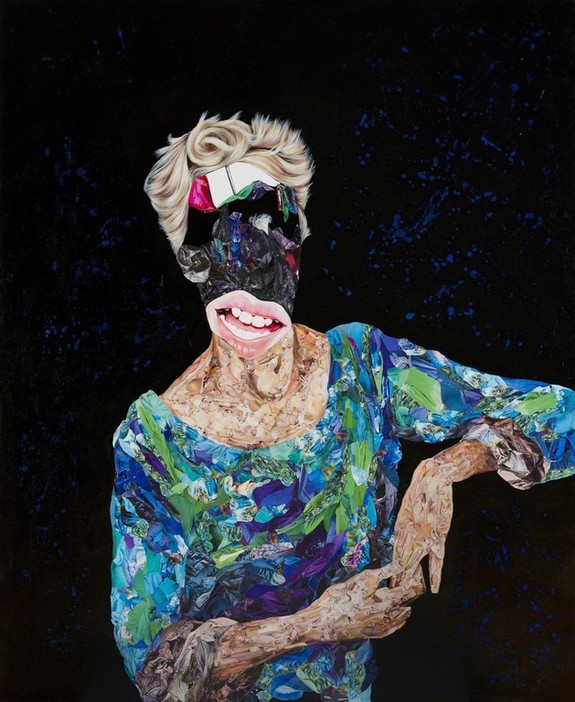

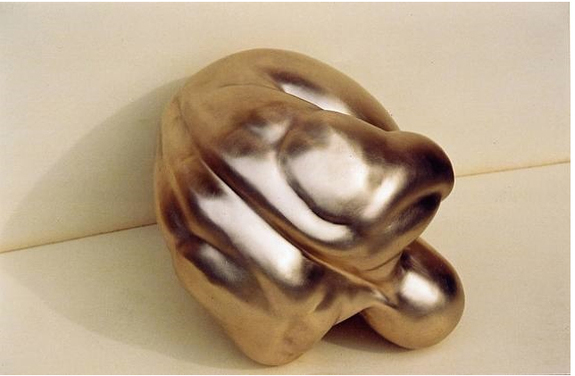

For four days, last October, a hundred artists from Africa took over Somerset House’s stately neoclassical wings and filled them with paintings, sculptures, installations, and photographs. Aboudia Aboulaye Diarrassouba’s energetic paintings of city life in Abidjan were displayed alongside Léonce Raphael Agbodjelou’s striking photographic meditations on the tensions between tradition and progress in the lives of the citizens of Porto-Novo, Benin. Meshac Gaba’s Diamants indigènes, a witty critique of consumer culture and neoliberal trade in the form of a travelling case filled with fake diamond-studded watches, sidled Romuald Hazoumè’s signature petrol can masks, with which he professes to “send back to the West […] the refuse of consumer society that invades us every day.”

In one of the rooms, spread across two walls, were eighty-six canvas squares by Nigerian artist Peju Alatise titled ‘Missing’. The squares, lined with West African textiles, each bearing the silhouette of a young girl, evoked ideas of anonymity, absence, and loss, paying a poignant, if chilling homage to the kidnapped Chibok girls.

A major new player

The occasion for this rich display was the second edition of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, a new event on the contemporary art circuit that is poising itself to become a major new player in the promotion and the diffusion of contemporary art from Africa. (The title 1:54 alludes to the fact that the African continent is made up of fifty-four countries.) Bringing together displays from twenty-seven galleries and featuring over a hundred artists, the fair is a new initiative that seeks to tackle the lack of visibility of contemporary African art on the international art market and in the art world at large.

The fair’s location and timing were carefully calculated. Organisers seized both on London’s status as an international art world capital and on the current dynamics playing out on its arts scene. In recent years, London institutions have already been moving toward a more global approach. For example, last November, Tate Modern introduced “Across the Board,” a 2-year programme of acquisitions, exhibitions and events that will place the spotlight on modern and contemporary African artists. At the time that the 1:54 Art Fair opened, there was also a generous handful of exhibitions of work by African artists on show across the city (including Wangechi Mutu at the Victoria Miro Gallery, Ben Owunsu-Ankomah at the October Gallery and Rotimi Fani-Kayode at Tiwani Contemporary). Moreover, like last year, 1:54 is timed to coincide with Frieze Week London, a major event on the annual art fair circuit that typically draws over 70,000 visitors among them the world’s leading curators and critics.

1:54’s model worked well last year and even better this time around. The fair doubled in size and so did attendance, with over 12,000 visitors attending over its four days (this was up from 5,000 last year). These visitors seemed to come from various geographic and professional horizons: in the hallways and the galleries, French could be heard just as much if not more than English, and gallery owners noted that there was an impressive mix of arts professionals, collectors and members of the general public. Sales, apparently, were good: on the last day of the fair, red dots (indicating a sale) could be seen in profusion beside names new and old.

Elephants and ebola

As an event that aims to ‘put the spotlight on Africa,’ 1:54 inevitably raises questions about the representation of African art and artists on the global stage. At a time when Western news outlets routinely continue to depict the continent as a single country (where lions and elephants roam free, where people are either dancing or dying of Ebola, etc…), one could wonder whether this type of event might suggest that African art is also a homogeneous field – heaven forbid, one made of wooden zebras and colourful baskets. Moreover, the longstanding associations between “Africa” and “Otherness,” the labels “African artist” and “African art” carry the suggestion that there is something that makes these artists and their work significantly “different” from artists and art from elsewhere in the world – something that justifies lumping them all together under a single title.

These are questions that have been asked before: think, for example, of the decision to create an “African pavilion” at the 2007 Venice Biennale, an event where European countries have had their own pavilions since the beginning of the 20th century. Asked for his perspective on the fair, renowned multimedia artist Barthélémy Toguo, who showed two of his signature watercolours as well as a video piece, warned against the dangers of such events perpetuating the marginalization of African artists that was at work in Venice. While he agreed that the fair was a positive initiative, “insofar as African artists do suffer from a lack of international visibility,” he pointed to the irony of using this type of label at a time when the world is globalizing. In his words, “to remove the label ‘African art’ would place the productions of African artists on par with those of others [at a time when] African artists remain highly under-valued.”

Africa worldwide

While 1:54 does not provide a straightforward answer to this question, it does do an excellent job of dispelling any misguided assumptions about what contemporary art looks like in Africa today. As its title indicates, 1:54 is a fair that seeks precisely to highlight the diversity of practices rolling out on the continent. It understands Africa in a purposefully wide sense: while the majority of artists hail from or are based in sub-Saharan Africa, several North African artists were presented as well (Younes Baba-Ali, Fayçal Baghriche, Mohamed El Baz, to name but a few). The roster of artists represented also included both those working on the continent and those working in the diaspora.

A further question raised by 1:54 is whether an art fair can truly give insight into practice of art in Africa today. Fairs are notorious for putting sales above art. As a result, they often privilege either the flashiest or the most conservative of works. In addition, they are often so sprawling that their space becomes utterly impossible to navigate. It then becomes difficult to appreciate the aesthetic and/or critical impacts of the works of art on display. As for these works’ relationships with other pieces, or how they fit into artists’ broader trajectories, forget about it.

On this score 1:54 fared well. The layout of the booths, each set up in individual rooms lined up along long hallways, allowed for a sense of intimacy between public, professionals and works. The fair’s public programme, “Forum,” offered context and critical framing for the art displayed in the galleries, thus providing a counterweight to the commercial dimension of the fair. The programme was curated by Koyo Kouoh, the founder and artistic director of the RAW Material Company in Dakar, and featured panels, presentations, and artists’ talks by leading thinkers, cultural operators and practitioners on a wide variety of topics.

A visa for the work, but not for the artist

The only hiccup in this impressive programme occurred on the last day, when Congolese photographer Sammy Baloji was forced to give his talk via video conference due to UK authorities refusing him a visa. No mere tragic anecdote, this incident should be taken as a pointed reminder that 1:54 is not a catchall for the problems affecting the production and dissemination of contemporary African art. Baloji’s case is a tragic but all-too-common example of the indescribable hoops that African artists must jump through to lead their careers in the present geopolitical landscape. It is a jolting reminder of the systemic inequities that frame 1:54 and that give it much of its raison d’être: whereas the art market is oiled with all sorts of shady money so that works of art can circulate across the world, the movement of artists remains checked by prejudice and paranoid immigration policies.

1:54’s greatest virtues arguably reside in its humility and its openness to the future. In her closing remarks, fair organiszer Touria El Glaoui alluded to the fact that 1:54 could one day become obsolete as African art becomes integral to international art fairs, public art collections and exhibitions. Meanwhile, as long as that is not yet the case, there is talk that 1:54 could travel to the continent. Let’s hope it does.

Lara Bourdin is ZAM's arts editor.