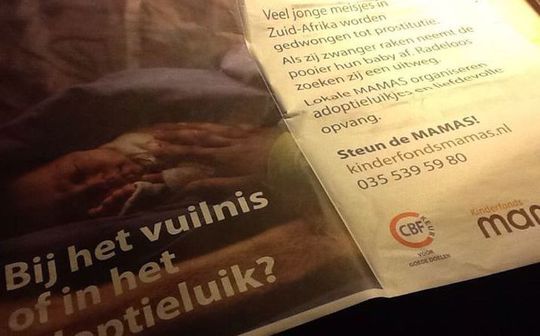

Charity claims that ‘babies’ are snatched away by ‘pimps’ from desperate ‘young girls who are forced into prostitution’ in South Africa. True?

The former Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund branch in the Netherlands, now renamed ‘Children’s Fund Mamas’ (Kinderfonds Mamas)(1), is raising funds for adoptive services for babies whose mothers, it says, are ‘young girls’ who are ‘forced into prostitution’ in South Africa. Reason: ‘the pimps take the girls’ babies away when they get pregnant and they desperately need a way out.’

But online available surveys and reports on sex work in South Africa dispute the portrayal of teenage sex workers as ‘forced’ into prostitution, with ‘pimps’ snatching away their babies. A comprehensive nationwide survey conducted by the NGO Sex Workers’ Education and Advocacy Task Force (SWEAT) in 2013, which included all ages, found no cases of girls or women who were forced by individuals (pimps or traffickers) to do sex work and not one of concerns about baby snatching by ‘pimps’. A ‘Human Trafficking Fact Sheet’ researched by Africa Check at the University of Witwatersrand only found eight cases –since 2001- of women who had reported forced prostitution by ‘traffickers’, but there was no baby-snatching reported in these cases either. Other reports on teenage sex workers all concur that social conditions like a dysfunctional home life, poverty and drugs keep young sex workers on the streets. Pimps are part of the situation but these, the reports concur, are also most often the girls’ boyfriends. Violence from pimps was reported in the SWEAT survey, but only in 8 % of cases. In comparison, sex workers reported violence from clients (57%), police (53 %) and even fellow sex workers (17 %) much more frequently.

According to SWEAT, fear of baby snatching had been reported by a number of sex workers who were mothers. However, these fears were not directed at pimps, but at police and social workers ‘who take away kids because they feel that a sex worker is an unfit mother’, said SWEAT director, Sally Shackleton. Shackleton added that, to address the problem of ‘baby-snatching’ by social workers and police, SWEAT’s new project ‘Mothers for Future’ proposes safe houses for sex workers and their babies. These houses would also welcome drug-addicted sex workers, who form the vast majority of teenage sex workers.

Shackleton: “The option of shelter for drug-addicted sex workers doesn’t exist anywhere else. Virtually all shelters in this country will only accept you if you are clean –and it is very difficult to get clean on the streets.” In contrast, the shelter, New Beginningz, for which the Mamas Childrens Fund is raising donations, is only for babies and does not cater for their mothers, whether addicted or not.

Not in the business of spreading lies

Asked why the Fund is less than truthful in its advertisement, spokesperson Frits Strietman assured ZAM that ‘this is all absolutely true. There are hundreds, thousands of such cases.” Cases of pimps taking away babies? “Absolutely.” Strietman said that one of the people the Fund works with in South Africa, director Tahiyya Hassim of the New Beginningz shelter in Pretoria, would contact ZAM to provide supporting evidence of the claims in the advert.

Hassim then emailed ZAM Chronicle a description of the situation of street girls in the Pretoria area. She narrated cases of very young girls who had been sexually abused on the streets or even by own parents (in one case, a child had been delivered to a brothel by her parents in exchange for a lounge suite). Hassim mentioned ten cases, spread over ‘the years when I was involved’, where girls could be said to be ‘forced’ to do sex work because they were so addicted that they were not able to leave the pimps who were supplying them with drugs, ‘which made them more compliant’. Her observations concurred with those in the SWEAT reports that said that drug dependency, mostly on boyfriends who also worked as pimps, was keeping girls in sex work.

Concerned friends

On the issue of what happens to babies of sex workers in these situations, Hassim said that babies are often brought to her shelter, either by the girls themselves or by ‘concerned friends’ and that it had happened in one case by a ‘father’ of the baby who was also the pimp of the girl. She added in a subsequent email that another girl had told her that these pimps ‘take the babies away’ because the girls needed to get ‘back to work’.

Asked if this happened against the wishes of the girls, Hassim said that it had happened once that a girl “came to ask after her baby,” but that girls were mostly ‘too drugged and too scared’ to leave the street life and start afresh. She added that it would also not be a good idea for such a girl to stay with her child. “There are very few young commercial sex workers (…) (who) condone raising a child in those living environments and circumstances. Either they come to us for help to remove the babies and give them up for adoption or social workers remove their children and place them in Foster Care.” (It is then hoped that) “the mother would miraculously sort out her life in two years and come back to claim her child once again to go off and be a happy normal family.”

Hassim said she could understand why most shelters would not accept young drug-addicted sex workers mothers together with their babies because the mothers ‘would rob and kill for their drugs’, and that much more money would be needed to equip centres for such tasks, whilst the South African government was not funding NGO’s such as hers and was generally ‘failing children in need of care an protection.’

Missing the point

Should Mamas Childrens Fund pretend that it is somehow protecting desperate girls from baby-snatching pimps, whilst the reality is clearly much more complex than that? Mamas Childrens’ Fund spokesperson Frits Strietman feels that ZAM is missing the point. “We have a situation of violence and despair and exploitation, in which pimps are part of the problem. And indeed these pimps are often boyfriends, even relatives and neighbours. The situation is too gruesome for words and it is a situation of force. In that situation, the girls need a solution for their babies. That is what we say in the advert.”

But you say that pimps take the babies away from the girls, whereas it’s the social workers, including the ones you work with, who do that.

“What we say is that the girls are living in a situation of force and violence. They are desperate and they look for a solution for their babies. I don’t think you understand the situation.”

The situation is serious. But you claim in the advert that pimps force ‘desperate’ girls to give up their babies and you suggest that this is against their will. Whilst the truth is that in the cases we know of, the pimps, and the girls themselves, and concerned friends, gave the babies up for adoption, and that is exactly what you support.

“I don’t understand your point.”

Aren’t you framing the problem untruthfully?

“I don’t agree. There needs to be a solution for the babies and the girls are desperate.”

Doesn’t the framing in your advert lead people to believe that supporting your adoption service is the only answer? Others who work with sex workers, like SWEAT, are critical of adoption being presented as the only way out. They report that sex workers sometimes go into hiding with their children to escape from the social workers. SWEAT is proposing safe houses where sex worker mothers, including teenagers, and their babies can live together. Even if they are addicted to drugs.

“We are willing to support all projects that help to address this terrible suffering. Why do you presuppose that we would not support that type of project?”

Would you?

Possibly. We support many things. And we are guided by the people in South Africa themselves.”

But by which people? The strategies proposed by SWEAT versus those of New Beginningz seem mutually exclusive. Won’t you have to decide at some point which strategy you support? And inform the public truthfully about these choices?

“Again, we support everybody who tries to help these girls, as long as it fits with our means and our policies. You are very confrontational. I really don’t think you understand the situation.”

Evelyn Groenink is ZAM Chronicle’s investigations editor

Notes

1. The Dutch branch of the Nelson Mandela’s Childrens Fund changed its name to ‘Kinderfonds Mamas’ in 2010. “Because the South African head office wanted to do more in terms of policy and advocacy, and we wanted to continue directly assisting projects”, explains spokesman Frits Strietman. The 2012 Annual Report of the Fund refers to ‘being obliged’ to drop the name of Nelson Mandela from its name. It further speaks of ‘damage’ sustained by the institution as a result in 2011, but happily reports that the number of donors has been ‘increasing again’ in the year of the report.Bibliography

The perused reports, dated from 1994 to 2014, are:

Sex workers in South Africa: a rapid population size estimation study (2013)Mothers of the Future program proposal, SWEAT, 2014 (no link)

Africa Check’s human trafficking fact sheet (2013)

Adolescent girls at risk: the GIRRL programme for assistance to teenage girls in informal settlements (2012)

“Selling sex in Cape Town” , Chandre Gould and Nicole Fick, 2008

“Juvenile prostitution, an investigation’, Stephen Louw, 1994, done in collaboration with the Johannesburg Hillbrow-based ‘The House’ group