Anas Aremeyaw Anas exposes what should be changed in Ghana.

“Six persons died yesterday when a Mercedes Sprinter bus with registration number VR 5044-14 somersaulted several times at Sege on the Tema-Aflao road.” This is written on Anas’ Aremeyaw Anas’ Facebook page: not because he is a traffic news reporter, or because he even knew anybody on that bus, but because his latest crusade is directed at fraudulent driving licenses.

After bread production, border control, the department of social welfare and the police itself, the investigative undercover reporter has now taken on the licensing department in his country, Ghana. The footage catching the ‘soul takers’, -as Anas calls the corrupt officials who allow incapable drivers on the roads and thereby cause deaths- has been shown in Accra’ national theatre and has led, once again, to the firing of many, and other presidential measures to improve the work done by the state.

It is not about the 'big guy at the top', it is about fixing the system, says Anas

“People ask me why I go for the low level officials, and not for the big guy at the top who gets all the money”, Anas explains when we meet on the sideline of yet another journalism conference (he attends many, usually to make a provocative presentation in which he attacks common journalism do’s and don’ts; more about this later). “But where is that big guy at the top who gets all the money? There is not one such guy. The whole system is bad. When policemen only service the public in exchange for a wad of banknotes, it isn’t one guy who gets all the money. They are all in it. They must all be exposed until they start doing their jobs.”

The fear of Batman

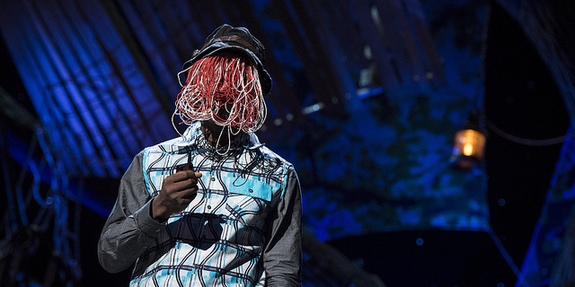

And exposing he does, instilling the fear of God, -or Batman if you like since Anas, like the Caped Crusader, never shows his face in public-, into tens of thousands of public servants in Ghana, who know that any hapless customer before them could well be him. Anas’ work, having been broadcast and reported many times even outside of Ghana, has achieved recognition even from the government: a rare feat for an investigative journalist in any country. “The President is my friend now. He acts when he is informed of the issues that we expose.” And even though many state officials still habitually ask for bribes for their services, an increasing number is starting to understand that they can no longer do so with impunity. After all, any person in front of you could be Anas Aremeyaw Anas or a colleague from his Tiger Eye crew.

Anas has been a pedestrian on the streets of Accra, a cleaner in a brothel, a travelling Koran teacher, a school substitute, a psychiatric patient and a cocoa smuggler. He undertook that last job in 2010, after he learned that the country was losing millions in expected export revenue as a result of cocoa smuggling from Ghana into Ivory Coast. “The President of Ghana was concerned. A special taskforce – tens of thousands made up of personnel from Ghana’s security forces- had been formed to stop the smugglers, but even after months, that taskforce had made not a single arrest.”

There was a significant dip in cocoa smuggling after the practices were showed on TV

While undercover with the smugglers, Anas found out that some members of the special taskforce were aiding them. “They found suitable paths to cross the border with bags of cocoa and even delivered contacts for the smugglers on the other side. In return, they received bribe money. I captured many of these transactions with my hidden camera.” The result was a special investigative report and a documentary film that showed the videos of bribe-taking officers. “When the story broke, more than fifteen officers were charged. The trial of some of these is still ongoing.” After the expose, the government of Ghana registered a significant dip in the smuggling and the revenue from cocoa exports picked up.

Mental health regulations and hospital practice improved after an undercover stint

Two years later, Anas went in as a patient in Ghana’s major psychiatric hospital. As if posing as a criminal, hiding his camera from ruthless armed villains, hadn’t been risky enough, he now allocated himself an actual psychiatric condition, learned to display the symptoms and even took the medication prescribed for this in the hospital. Speaking to him twice over the phone during his period, he sounded quite drugged both times and I was not the only one fearing for his actual health and sanity. But he recovered with a bang, delivered the footage and the report, which exposed inhuman conditions as well as a flourishing medicines and drugs trade by hospital staff. The work contributed to the adoption of a government strategy for comprehensive mental healthcare as well as a new Mental Health law.

The biscuit factory with the rats

He tackles private enterprise as well. At the start of his career, in 2008, he went undercover as a worker in an Accra biscuit factory, filming rats roaming freely in and around the food. The year after that, he infiltrated and exposed religious ‘schools’ that used children entrusted to their care as prostitutes and beggars. And in 2012, just after the coconut smuggling episode, he filmed the practices of criminals who were selling fake gold bars to unsuspecting international buyers. The evidence that got them convicted in court.

Perhaps paradoxically, when catching criminals, Anas often works with precisely the same state structures that he has exposed as ‘corrupt’ before. In the ‘fake gold’ case, he alerted police to come and catch the con men in the transaction with the foreign buyers. Anas was there to film the deal as well as the police arrival and the arrest. This practice has led to criticism from certain institutions and trainers in journalism. Aren’t journalists supposed to inform the public, rather than behave like policemen and vigilantes? How can a journalist expose bad governance whilst at the same time working with government?

Squeezing out the bad

He responds scathingly when such issues are raised at conferences and in public debates. “In a country with a malfunctioning state, you can’t just expose and criticise. Nothing will ever change if you stop there. There are good people in the institutions, who want to help to root out corruption and perfect the democratic experiment in my society. I do not hesitate when I get the support of such well-intentioned individuals, departments or organizations. We must work together to squeeze out the bad. You are either part of the disease or part of the remedy. I choose to be part of the remedy.”

Exposing the rotten apples helps to close the loopholes they use

It may be, he concedes, different for journalists who work in the ‘old’ democracies in the West. “The institutions in those countries are more established. It will not be easy for an official to sell a license in exchange for a bribe. Even if he wanted to, the system doesn’t give him that opportunity. In Accra, buying and selling licenses is almost normal procedure. We may subscribe to democracy, but that does not mean we have built up our state.” So corruption in Ghana is not an issue of a few rotten apples, but of a developing structure that is still full of loopholes. “Correct. By exposing the rotten apples I work with the people who are building up the systems and closing the loopholes they use.”

The spies of old

At a recent journalism conference in the Netherlands, Anas faced more criticism after he had explained the above. “They told me: you must not be an activist. A reporters’ job is only to inform people. But I later wondered if Western journalists aren’t motivated by social justice concerns. When I read their reports about Africa’s problems, or welfare cuts in their own countries, or the use of chemical weapons in Syria, they often sound as much inspired by a passion for truth and justice as I am. Maybe it is only my methods that are different. Though I am aware that Western journalists like Günter Wallraff have also gone undercover to expose injustice. ”

It is precisely the undercover method that allows Anas to explore under-reported terrain: the experiences of ordinary Ghanaians, many of whom live in an uncertain, challenging world that is almost unknown to the pampered national elite. It is only by pretending to be an anonymous, ordinary Ghanaian, after all, that he has discovered the practices of the quack abortion doctors that so many of his country’s women are forced to rely on, or the extortion rackets permeating the state’s public services, or the girls behind the railway line: underage street children, forced to make a living as prostitutes.

Anas: “A friend recently said she views my work as that of ‘the spies of old’, those who go ahead of their people to discover new land, and they come back to tell the people about their find.” There is still much ‘new land’ that we haven’t explored. Doing this, we re-evaluate our paths and consider which ones need pursuing and where we need a turnaround. My method of work, collaboration and pursuits beyond the story are, very simply, both products and tools of my growing society.”

And in his latest video, all grainy and capped and swag, he actually does look a little like Batman, too.

Note: Anas Aremeyaw Anas is the subject of the newly released documentary Chameleon by Ryan Mullins. The film takes the audience behind the scenes with Anas during his investigative work. Chameleon will see its world premiere at the international film festival IDFA and the film is nominated for the Feature-Length Documentary Award. Follow the film on Twitter for updates.