The World Cup made South Africans realise that the government should impress its own people as well

It is a narrow victory, but a victory nonetheless. Half of the people I ask if they would have the – first African – World Cup of 2010 all over again, give me a yes. It made them feel good, they say, it brought people together, white and black, rich and poor, and they would love having such a great experience again. About a third says no, however, and the rest is undecided. For those with doubts, it is the unfulfilled promises of a better life after the event that have frustrated them.

South Africans know the promises of job growth and prosperity came to not much, but they still wouldn't want to have missed the event

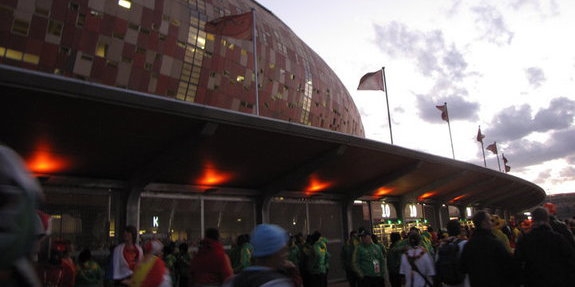

“It was great to see the international players and have those famous people so close by, but at the end of the day, the World Cup brought us nothing,” says Lucky, a security guard at the FNB Stadium, which hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the event in 2010. There is not much going on here on this Saturday afternoon, except for a private function at the adjacent South African Football Association Club House. Lucky explains that every now and then there is a match of the local soccer league, but other than that, the envisaged buzz of events here at this revamped prestige project, that shines in the winter sun like a massive terracotta UFO, has not materialised.

Sobering statistics

In a survey conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa in 2007, three years before the World Cup, half of the interviewed people believed that job creation and economic growth would result from the tournament and a third expected to personally experience some benefits in terms of job opportunities and income. But an impact study by the University of Stellenbosch after the event showed that, even if there was a significant increase in tourism to South Africa after the announcement that the event would be held in that country, ‘only few’ jobs were created. The Stellenbosch research estimated the World Cup contribution to the GDP at 0.1 %, (then roughly US$ 290 million), about five times lower than an impact commissioned by the government itself, and thirty times lower than the government had predicted before the event.

Meanwhile, the total revenue accrued to FIFA was around US$ 2,7 billion tax free – “making the first World Cup in Africa the most profitable in FIFA’s history”. Sobering statistics indeed.

The revamped stadium still pays Lucky and his colleagues for their round the clock security job, but an exciting job it isn’t, and they spend it mostly listening to mbaqanqa music on Lucky’s cellphone. “In 2010,” muses Lucky, “the government was motivated by impressing the world. Maybe they don’t want to impress us –the people. I suppose we must remind them that we are also here.”

The trendy neighbourhood market in Johannesburg’s inner city Braamfontein area, however, is divided. Porter Sipho Dube echoes the security guards’ disappointment (“When you are hungry, you can’t enjoy anything, not even the World Cup.”) and a middle aged blonde man agrees loudly. “South Africans are losing hope in their government,” he says. “The only people that benefited from the World Cup are FIFA and the construction companies.”

But Nombongo, a student and part-time singer at the market, shakes her head at the negative comments. “These kinds of places wouldn’t have existed if it wasn’t for the World Cup,” she remarks, referring to the present hipsters and cool kids of all races. “The World Cup made it okay for all of us to share social spaces like this in close proximity. It was there before but I think it’s less forced and less superficial now.” Nombongo says she ‘loved the ambience and unity’ the World Cup brought.

Drunk white people

And indeed, Soweto too is a bit different today. At the local Skate Park, which also houses a burgeoning punk music scene, skin tones seem secondary to agility with the board and or an instrument. This started with the World Cup, notes local resident Vero Skenjana. She has only good memories of the event, even of the ‘drunk white people’ who suddenly roamed the streets of her neighbourhood. “There was nothing to fear, you could walk around at night and you would find all sorts of people in the shebeens having a good time with each other. We were just people.”

Celebrating soccer together helped overcome interracial barriers

Young professionals Thembi and Zviko Mudimu were so enamoured by the 2010 tournament that they decided to go to Brazil this year to relive it all again. The married couple who are in their early 30s are avid soccer fans and often go to local Premier Soccer League games around Johannesburg to support their team Orlando Pirates. They want to witness once again, they say, “one of very few events that can unite people from all over the world.”

The couple have had to save up for the last two years to afford the more than six thousand Euros that the experience will cost them, but it is all worth it, they say. “We’ll be cheering for the four African teams – Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Nigeria – but I am also supporting Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. Zviko hasn't declared his support of any team but he bought a German flag and hat,” giggles Thembi.

Asked about the protests in Brazil against the vast expenditure for the World Cup, made whilst many people, like in SA, live in poverty in that country, Zviko reflects that the protests are justified. “Access to decent employment, health care, education and sanitation for all should of course be prioritised before the building of billion dollar infrastructure.” But hey, they are still going.

Protest focus

And maybe the world focus on the social upheaval in a World Cup country can actually help to bring change in the long run? South African filmmaker Yazeed Kamaldien has adopted this ‘protest focus’, which, paradoxically, might unite both World Cup fans and protestors, in his recent film about the preparations for the World Cup in Brazil. The title of the thirty-three minute documentary titled 'Imagina na Copa' ('Imagine, during the Cup'), refers to a common exclamation among Brazilians when faced with yet another local corruption case or services that don’t run smoothly. “Imagine (if such a thing would happen) during the World Cup!”

“The anger and energy at protests and the fearless opposition to government evictions (of poor people from their living areas) cannot be ignored. Anyone who is interested in the Soccer World Cup needs to hear these voices. Brazilians want the rest of us to know that it’s not all soccer, samba and supermodels but a very challenging reality,” says a passionate Kamaldien, who feels that South Africans did not fully leverage the world’s attention during the World Cup.

“South Africans bought the hype. We should have been more collectively vigilant and vocal about the bizarre spending of tax money on a project that did not fully benefit citizens. It is not that the Soccer World Cup is an altogether bad experience; it's just that the outcomes do not match the expense that citizens have to pay, while a few business and political elites laugh all the way to the bank. There is so much corruption surrounding every Soccer World Cup. It's a joke. We know that the construction companies that built the stadiums in South Africa were also involved in corrupt activity. It's sick what they get away with. Now people want to know what they can do to stop this kind of corruption.”

Remarkably, people did become more vocal and vigilant about state operations after the World Cup

Interestingly, the South African people – even if maybe belatedly – did become more ‘vocal and vigilant’ about their government delivering on public services in the aftermath of the World Cup. The Human Sciences Research Council, in a 2012 report on the social impact of the event, noted that several interviewees in disadvantaged areas such as Atteridgeville township in Pretoria, had stated they were now ‘more angry’ than before the World Cup, and ‘more determined’ to see protests against poor services through until the government would listen. One said that “because of the World Cup, we know now that the government can manage to organise things properly. So if we still don’t have good services, it is because they don’t want to do it for us.”

Social protests went up from seventeen events before the World Cup to four hundred and seventy in the year after

It is perhaps not a coincidence then that social protests in South Africa – after a lull during the Cup itself and in the immediate aftermath in 2011 – multiplied by almost a factor 30 in 2012. While protests in 2009 numbered a total of 17 during that year, in 2012 there were a staggering 470. The hype of protests went slightly down again to 270 in 2013, but is still on at unprecedented levels, with examples (though still too few and far between) of government responding and acting to address complaints. It is as if the people of SA agreed with security guard Lucky at the Soweto soccer stadium, when he talked about the government ‘impressing the world’, and it now being time that it ‘should impress us,’ and ‘that we should remind them (the government) that we are also here’.

The feeling that a country that hosts a World Cup should actually also be held accountable for better behaviour in all respects also echoed through in the words of Steven, gardener in Pretoria. He, when asked if he wanted to see another World Cup in SA, reflected: “Yes. They should bring it to South Africa again and again and again, until these guys here finally learn to play soccer.”

Kamaldien plans to screen Imagina na Copa at various venues, starting in Cape Town, and spreading across South Africa and beyond. Any persons interested in hosting a screening can get in contact with the filmmaker via This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Sara Chitambo is a reporter, photographer and filmmaker in Pretoria, South Africa.