The ‘smiling coast’ of Gambia is led by an insane dictator who keeps getting propped up with donor money.

The Gambia, the smallest country in Africa and a tourist destination since the 70’s known for its beautiful sunny beaches, used to be advertised with the slogan “the smiling coast of Africa.” Nowadays, however, it is above all known for (sex) tourism, rickety boats, increasing poverty, violation of human rights, anti-gay laws and ‘Great Leader’ rhetoric by its president Yahya Jammeh who also claims that he can cure aids. The European Union is trying to use its donor aid to pressurise Jammeh into better governance. So far without success.

Once, Yahya Jammeh was a skinny lieutenant, who promised to bring development and a better life for the poor. His own Jola tribe had traditionally been underdogs in Gambia: domestic maids and watchmen for the elite Mandinka. Their People’s Progressive Party (PPP) government, under then President Jawara, had been one of patronage. The rulers lived in the well-to-do suburbs Fajara or Bakau; their children were driven around in luxury cars. People complained that scholarships for overseas studies were dished out to the elite’s children instead of well-performing students from poor backgrounds. Young people were generally frustrated in the ‘old’ Gambia, where ‘the elders’ had all the power.

When Jammeh, then aged 29, and his fellow young lieutenants took power, they drew genuine cheers from the country’s youth. The accomplishments of the new regime also seemed visible soon: national television, a new airport and a university. All these three projects had been commissioned by the Jawara government, but Jammeh happily passed them off as his own.

Being careful with the servants

There was some redistribution of wealth, too –but only from individual members of the old elite to individual members of the new one. Many richer members of the former ruling PPP party, had their houses and assets confiscated by the military. A summons to various ‘Commissions of Enquiry’ that oversaw such confiscations could be prompted by any report made about you to the new rulers. In the Gambia in 1995, people warned one another: “Better be careful what you say, even in your own compound, because of the servants.”

The new regime of angry young soldiers belonging to Jammeh’s AFPRC (Armed Forces Provisional Ruling Council) was poor, ill-educated, and full of envy. They had no experience in managing even a small project or a shop. It had no policies for development, let alone the creation of opportunities for all the people. In practice, confiscating assets was one of the few things they were good at.

Jammeh, the son of a poor Jola family, is now by far the richest man in Gambia. Together with his Moroccan-Guinean wife Zeinab he owns businesses in all sectors of the economy and many properties in and outside Gambia. He has the use of three airplanes, which are used for his travelling but also for the many shopping trips his wife makes to Paris, New York or Nairobi, a number of new BMW X6 limousines at US$ 350,000 apiece, and an army of body guards and praise singers. His entourage of government and party loyals, and a small group of Lebanese businessmen who have benefited from government trade, do well too. The rest of the country, not so much.

Floating coffins

Lack of investment in agriculture –the state often doesn’t have cash to buy farmer’s crops, and rarely distributes quality seed and fertiliser, or provides any other services- have resulted in groundnut production dwindling from 150,000 tonnes to 30,000 tonnes since former President Jawara’s days. The rural population now often does not have enough to eat. Besides Jammeh’s own Aids cure there are few medicines in the hospitals, civil servants don’t get paid and infrastructure is not maintained. Electricity blackouts are the order of the day. Now that many businesses have left the country because of over taxation, a cash-hungry Gambian Revenue Authority has taken to harrassing women with small stalls at the tourists markets.

When, recently, government money was spent on ferries, -sorely needed in this country split by the Gambia river-, the vehicles bought from Greece at a cost of millions of Euros, turned out to be 27 years old and unsuitable for docking at the existing landing sites. Old ferries, dubbed ‘floating coffins’, were taken ashore in March for repairs and there hasn’t been a ferry operating since. On the 6th of April, news presenter Ramatoulie Jallow at the state news service GRTS (Gambian Radio and Television Services) was fired after she had asked the President a question about the grounded ferries during a press briefing.

Unpatriotic Gambians

Other critics have experienced similar or worse discouragement. ‘Unpatriotic Gambians’ in the opposition and the media face harassment, arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detention, closure of their premises or even lifelong imprisonment. In 2012, nine prisoners on death row were executed; three of these had been found guilty of ‘treason’.

On 25th October 2012, Bubacarr Ceesay, vice-president of the Gambia Press Union and a journalist who had investigated purported links of Jammeh to organised international arms and drugs syndicates (1), received an anonymous letter from a ‘team of patriotic killers’ who knew where he lived, ‘in Tallinding near the small market not far from Churchill's Town.’ It said, among other things, that ‘You (cannot bring) the Tunisian, Egypt, Algeria, Seria (sic) and Libya situation here” and that he would be killed ‘for the love of our country and our president.’

Four months later, on Friday 11 March 2013, Ceesay was picked up on the street by National Intelligence Agency (NIA) officers, bundled in a car without number plates and held incommunicado over the weekend. If he had not managed to alert a passer-by, telling the man his name, and mentioning the NIA, worse might have happened.

By recruiting from his own Jola community in the ever expanding security structures and in the higher echelons of government, Jammeh has maintained an ethnic-based loyalty that still results in wins for him at election time, even though less and less people are voting. But an open revolt seems unlikely. People are scared to be seen gathering in today’s Gambia, where even youngsters playing football are sometimes harassed and rounded up. The memory of fourteen students who got killed during a demonstration in 2000 is still vivid.

Cheers and embarrassment

One therefore dutifully cheers when the ‘Alhaji (holy man, CC) Dr. Professor Yaya Jamus Junkung Jammeh’, as he has ordered he must be addressed, passes by, not lean anymore but very big indeed in his giant white flowing boubou, smiling, while his praise singers and bodyguards toss biscuits and T-shirts into the crowd. Business people in the tourism industry still show up to humour him and clap at his parties. Unrest and protest would not be good for this important business sector: tourists must keep coming and one must smile.

A large part of Gambia’s better educated people now live abroad. In their blogs and online news sites, they often express shame and embarrassment about the dictators’ bizarre antics, like his penchant for issuing disruptive decrees that change working hours, or the country’s official language, or force all Gambians to stay at home and burn their garbage every last Saturday of the month. (It causes pollution, but saves the government from having to run a waste disposal service.)

Chicken change

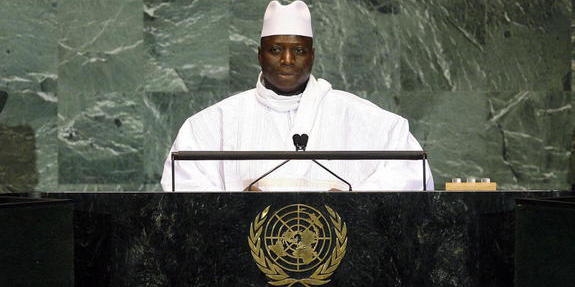

Jammeh is equally erratic when it comes to his foreign relations. In October 2013, a week after accusing the ‘colonial’ West of ‘lecturing Africa about human rights’ in a speech before the UN, he suddenly decided to leave the Commonwealth. A month later, he severed relations with Taiwan, which had refused to accede to his demand for un-receipted cash payment in excess of US$ 10 million. In January that year, he had already referred to ‘blackmail’ in response to the European Union’s demands for better governance and respect for human rights. He then also accused the EU of trying to ‘destabilize’ the Gambia and ‘force gay marriage’ on the country. He declared that the Gambia didn’t even need the ‘chicken change’ donor money.

Remarkably, however, he has also said the opposite: in a recent speech broadcasted on national TV, Jammeh blamed ‘all the suffering and hardship for the people’ on Western donors who were ‘withholding aid’ to ‘increase poverty’.

Fears of a donor

The European Union has contributed more than 65 million Euros to Jammeh’s government between 2008 and 2013. It is now planning to send another 150 million Euros his way over the next seven years. The question is why.

The fervently anti-Jammeh ‘Freedom Newspaper Online’, an online newspaper published from USA by Gambians living in that country, is dead set against it. It wrote in November 2013: “The time is now for the European Union to show President Jammeh and his government some muscle to salvage the Gambian people from an increasingly ruthless despot. Targeted sanctions would have virtually no direct impact on the population, yet it would carry a great deal of symbolic significance (...). It would further demonstrate that the European Union is indeed with the Gambian people and that it is willing to finally take necessary measures to end despotism in The Gambia.”

But European countries, -particularly Spain and Italy-, fear that lessening of aid may increase poverty and send more migrants its way. In relation to the conflict in neighbouring Senegal’s Casamance region, where Jammeh has been supporting an armed independence movement, there are general security fears related to ‘Al Qaeda’. Other fears concern the risk of expansion of the cocaine trade that is already present in the Senegambia and Guinea Bissau -in which, interestingly, Jammeh is rumoured to be personally involved (1). As so often, therefore, donor money is not a tool of charity, but one of influence.

But should one, in order to curb drug trade, support a leader who has often dealt with drug- and other criminal peddlers? Should a regime which oppresses people be propped up out of fear? Is it reasonable to keep giving money to the ‘fat white chicken’ in an effort to stop people from migrating out of his country? Recognising the paradox, the EU has engaged in a so-called ‘Article 8 Dialogue’ with the Gambia, meant to ensure that aid moneys are put to good use. Of course, such a ‘dialogue’ can only work if there is an actual stick -cancellation of aid- behind the door.

If the stick will work this time remains to be seen. On Tuesday, April 8, this year, in a meeting with EU representatives in Banjul, Jammeh promised that he would address some of the European concerns. His need for cash could have prompted him to do this: he was, after all, last seen unsuccessfully begging money from Turkish banks and the Saudi government. “We had a very frank discussion on an array of issues, which was very productive,” Dakar-based EU Ambassador Dominique Delacour said after the meeting.

Activists ask for travel bans

But progressive activists in- and outside Gambia fear that further EU support may aggravate, rather than help the situation. They have asked for targeted punitive sanctions, especially travel bans for officials, until the EU’s demands have been met. Massive visa denials by some EU countries –notably the United Kingdom- to Gambian government members were an important reason for Jammeh to even come to the meeting. Extending the pressure in this way may therefore be more effective than simply giving the fat white chicken money again.

(1) Scary Tales of Tiny Gambia Being the Headquarters of the Mafia World, by Bubacarr Ceesay.

Cecilia Cachette is a pseudonym. The author has visited the Gambia regularly since 1975 and has many friends in the country.