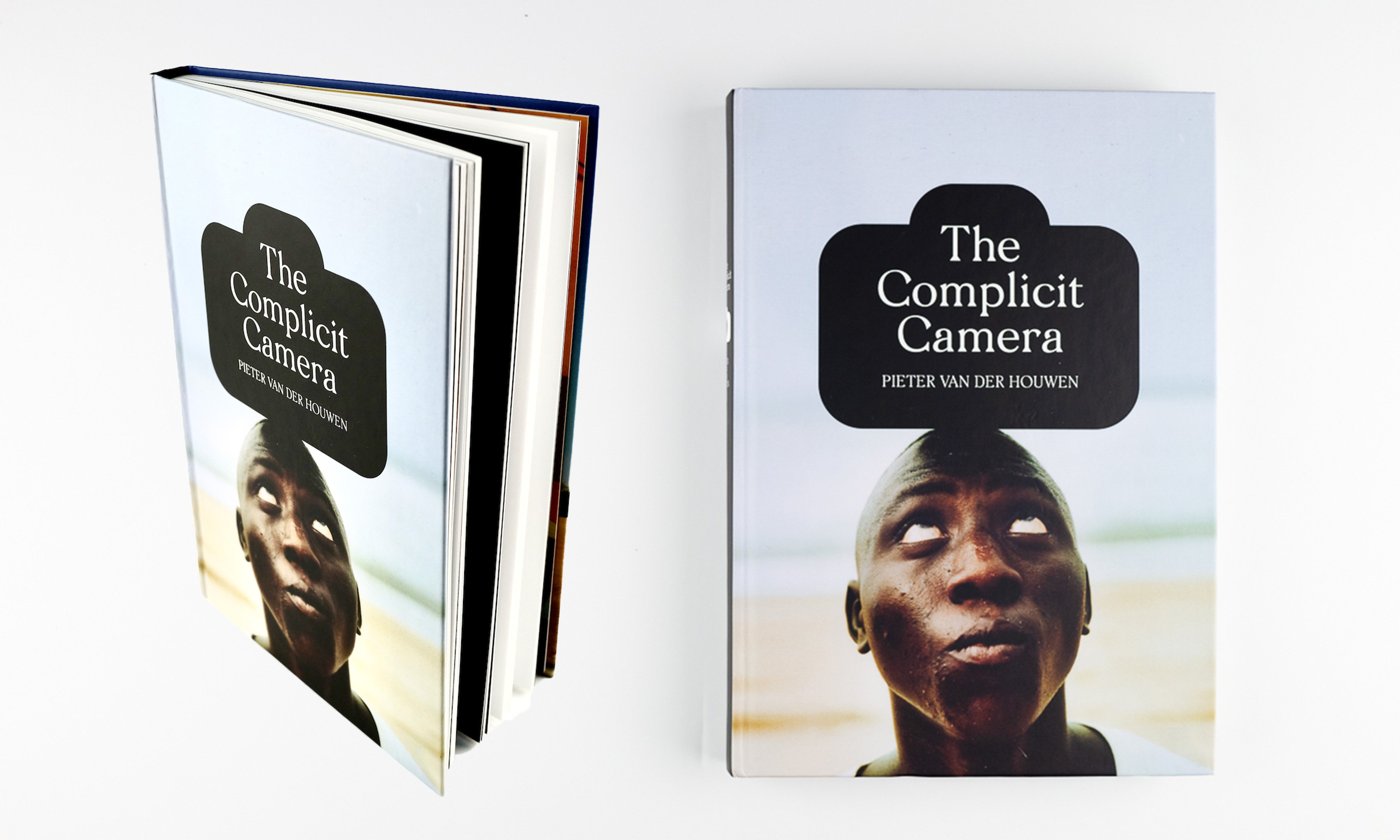

In his book The Complicit Camera, photographer Pieter van der Houwen investigates how his images contributed to a (mis)understanding of Africa. This is his preface to the book.

As a photographer, I have had the privilege of working in approximately twenty-five countries on the African continent. During a period of nearly thirty years, my approach to photography on this vast and complex landmass has changed as much as the continent itself: from a naïve and youthful photographer fuelled by a “white saviour complex," convinced that my photography could make a difference, to a more seasoned and perhaps even cynical journalist.

Recently, while working in Nigeria, I couldn’t escape a feeling of redundancy. It was as if the themes I had pursued for years were not my own; they belonged to my African colleagues. The digital age has empowered a community of talented African photographers. Social media sites such as OneDayAfrica provided the ideal global platform to showcase and distribute their innovative photography. The Market Photo Workshop, the celebrated photography school in Johannesburg, had become inundated with applications by young photographers from all over Southern Africa. A new era had announced itself, one in which Africans documented their own reality.

Many images were devoid of any context: no names, professions or even locations

Not long ago, I was approached by an advertising agency with the request to contribute to a publication dedicated to sustainability. I decided to write about the Senegalese rapper and activist Pacotille. I had photographed the musician in the early 2000's for a music publication. Now I would focus on his politics and activism. This meant that I had to find his image in my somewhat chaotic and neglected analogue photo archive. The exploration of twenty-five years of African images would prove to be a revelation. Looking back, it became evident that I had contributed generously to the proliferation of images of black Africans taken by white photographers. Many images were devoid of any context: no names, professions, or even locations. A collection of anonymous people were photographed for the sole reason that they were African. The absence of captions made me complicit in the construction of “otherness.” Or, as Susan Sontag insists, “to grant only the celebrated their names reduces the rest to archetypal illustrations of their occupations, ethnicities, and predicaments."

Today, it would be inconceivable for me to photograph someone anonymously and without consent. It had taken me years to realise that documentary photography had to rise above the aesthetic. Interaction with my subjects is essential; for me, a portrait has to be a joint venture, a true collaboration between photographer and subject. The Complicit Camera should not be viewed as an apology for my misjudgments; rather, this book should be regarded as a personal reflection on my work and how it interacted with the media industry. I do not denounce the social relevance of photography. I do, however, question the impact that photography has on our perception and understanding of the African continent.

About Pieter van der Houwen

His first encounter with the African continent was when he was recruited from art school by the Dutch government to illustrate a book on aid and development. After this initial introduction, he continued to work on the continent for almost three decades. He soon came to realise that the depiction of Africa in Western media outlets was a far cry from his own experiences. “It was as if Africa could only be understood through a negative interpretation." The University of Glasgow allowed him to customise his Masters in political communication around his photographic work in Africa. His research in Glasgow pointed him towards the contemporary African Diaspora, resulting in the publication African Tabloid and the documentary The China-Africa Connection (VPRO Television). The Complicit Camera seeks to breach the void between academia and the media industry.

The Complicit Camera, published by ZAM, will be released on September 25, 2024. Order here.