While most of his iconic images have returned to South Africa, some remain in European institutions.

Ernest Cole was an acclaimed apartheid-era South African photographer who died in exile in New York 34 years ago. The recent return of vintage Cole images to South Africa from Sweden needs to be seen in the context of a recent wave of repatriation of valuable African heirlooms. The Cole saga is not yet over, involving a tussle over rights of ownership of his remarkable legacy. This is a close-up perspective from a photographer.

In recent weeks the Hasselblad Foundation handed over 497 Ernest Cole vintage prints to Leslie Matlaisane, the chairperson of the Ernest Cole Family Trust. The press release described this moment as a celebration that “marks a return home for Ernest Cole’s work. We’re proud to have played a role in preserving this remarkable photographer’s archive.”

In June this year, Cannes awarded the Golden Eye Best Documentary award to a documentary film on Cole by Raoul Peck. Read together, it would seem that Ernest Cole’s legacy has reached a high watermark with the return of the Hasselblad Foundation images to his heirs. Beneath the veil of public relations and international attention, there remain some hard questions.

Cole died of pancreatic cancer in a hospital in New York City, a week after Nelson Mandela was released. He watched Mandela’s “walk to freedom” on TV with his old friend the New York Times journalist, Joe Lelyveld, with whom he had worked in South Africa in the 1960s. In 1966, Cole left the country when the security network was closing in on him after extensively documenting black life under apartheid. His negatives, contact sheets and prints were smuggled out of the country through a network of friends and supporters, including Lelyveld.

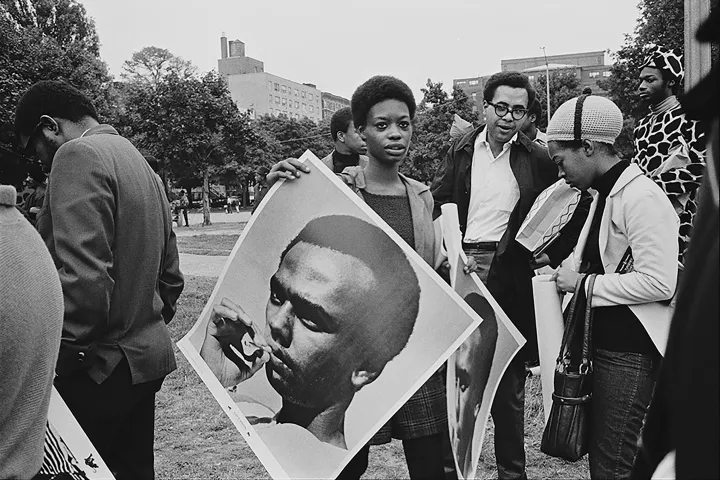

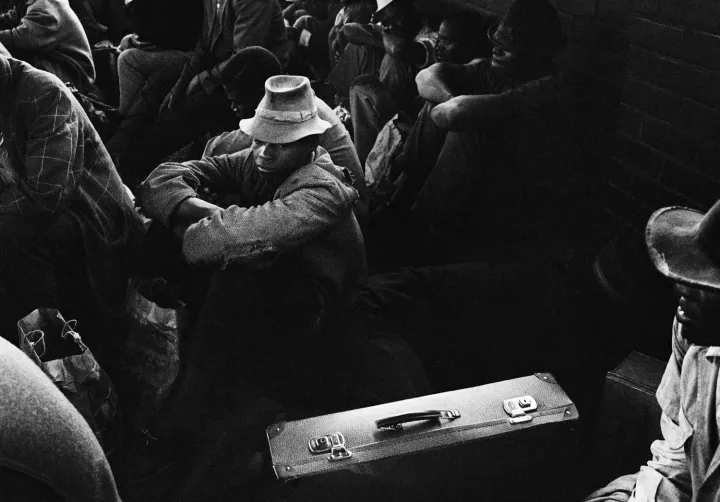

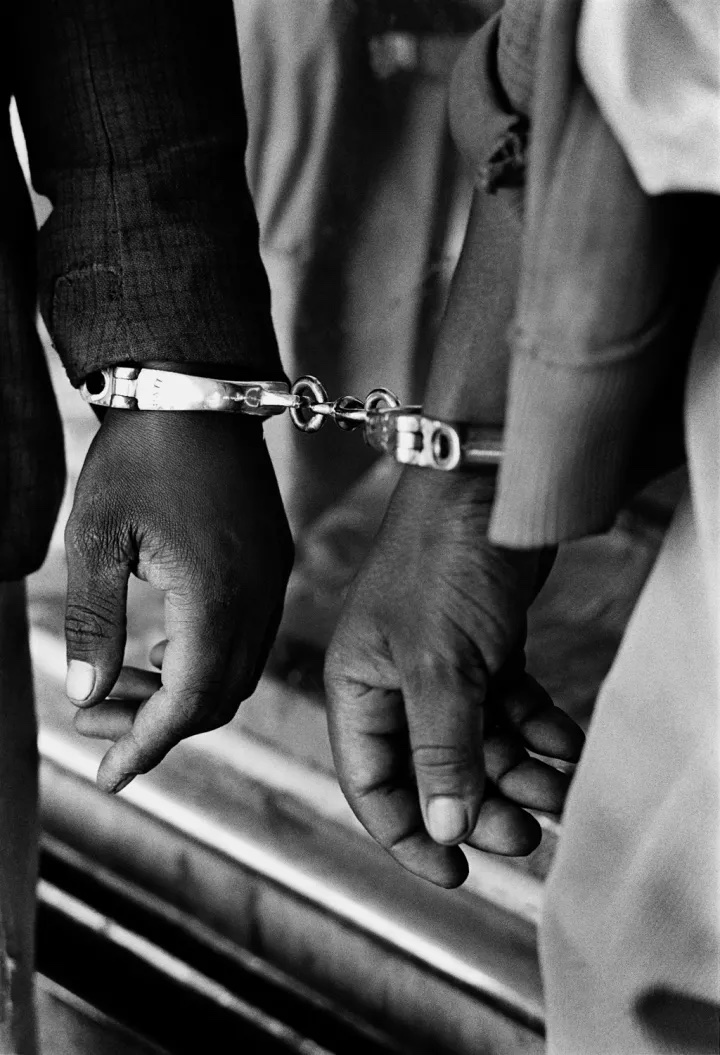

A year later, House of Bondage was published to great acclaim. It became a seminal reference point in understanding the inhumane apartheid system. Cole had methodically produced 18 essays, from the mines, education and health to the dreaded pass laws system. He even got himself arrested to take a set of images about pass law arrests.

These images and other iconic photographs from the book were used frequently during the anti-apartheid Struggle. Lelyveld wrote the introduction, importantly contextualising Cole’s images. He remained a close friend throughout Cole’s life. Museum of Modern Art curator Oluremi C Onabanjo encapsulates Cole’s contribution to South African photography as well as to the larger history of photography in her essay in the new House of Bondage edition, published by Aperture in 2022: “Deftly harnessing image and text, Cole mines the grounds upon which Black life in South Africa during the twentieth century was surveilled, regulated, and subjected to forms of punitive existence.

“His lucid analysis and sophisticated visual grammar produces a blistering critique that reverberates not through the register of the spectacular, but rather through the relentless documentation of so-called unremarkable scenes.” Cole and his book were banned soon after publication in 1967. He never returned to South Africa, and like many other South Africans lived and died in brutal exile from his homeland. However, for a few years Cole rode on the success of House of Bondage and associated exhibitions.

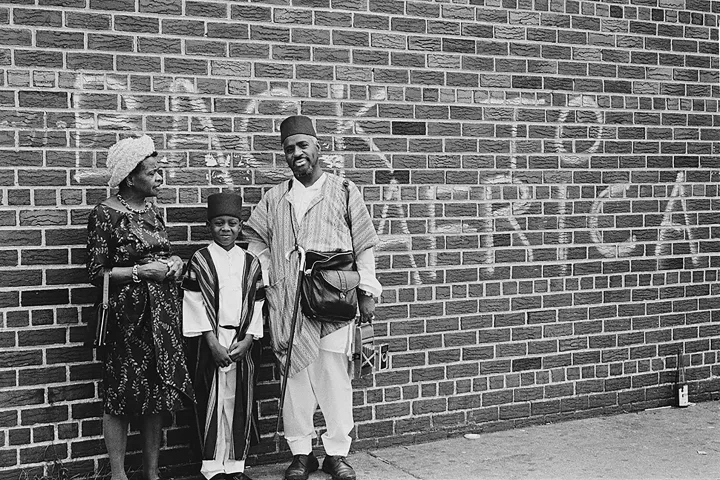

From 1968-1972, he was sponsored by the Ford Foundation on an extended assignment to document black life in America’s rural and urban areas. But after this period and for the rest of his life, he struggled, both financially and emotionally.

Life’s work vindicated

In his last days, watching Mandela’s release from prison with Lelyveld when calls for a free South Africa seemed universal, he must have understood that his life’s work had been vindicated. However, the return of the Cole images to South Africa, 34 years after his death, needs to be seen in the context of a recent wave of repatriation of valuable African heirlooms.

Notably, the Benin Bronzes and other valuable assets with deep cultural and spiritual resonance are slowly being returned to their rightful owners. At the heart of the issue are the dubious methods in which the appropriation of this material was made from its source, and the asymmetrical way former colonial and developed countries have created museums and cultural institutions. At a recent conference on archive and museum heritage in South Africa, an African delegate bemoaned the fact that 90% of Africa’s cultural heritage lies outside the continent.

Digging below the surface, the repatriation of Cole’s legacy has been shrouded in mystery. Unpacking it is like living through a John le Carré novel.

One common thread that stands out is that there are a number of parties and institutions associated with Ernest Cole who have “claimed” his legacy (vintage prints and negatives) as their own, ignoring the rightful owners, his family, since his death. Lelyveld wrote to John Hillelson in 1991, a year after Cole’s death. Hillelson had represented Cole for many years and periodically sold Cole’s work through his agency in London. In the letter, Lelyveld made three remarkable and significant statements. One is that he believed Cole did not have a will. Two, he requested that if there was any revenue from sales, the money should go to Cole’s mother in Mamelodi. He even provided a phone number for the family. Three, obviously in response to a question from Hillelson, Lelyveld wrote that “Ernest always led me to believe he had negatives in Sweden.”

Hindsight

In trying to piece the Cole puzzle together with the advantage of hindsight, there are a number of elements that simply do not add up. In 2010, Gunilla Knape, then research director of the Hasselblad Foundation, produced a book and an exhibtion of 100 images from the Hasselblad Foundation archive on Ernest Cole.

The exhibition travelled widely throughout South Africa and to Europe and the United States. The book and exhibition were predicated on the position that Cole’s negatives were irretrievably “lost” and the Hasselblad Foundation possessed a number of “lost” and highly valuable Cole prints. This is of course refuted by Lelyveld in the letter referenced above to Hillelson where he says Cole had told him his negatives were in Sweden.

Representatives of the Cole family began petitioning the Hasselblad Foundation after his death for the return of his work. After the exhibition and publication of the Hasselblad Foundation book, Ernest Cole: Photographer in 2010, the family renewed their efforts for the return of the images. They believed, as they had continuously asserted, that the material belonged to Cole’s heirs. In many exchanges and over more than a decade, the Hasselblad Foundation contested this claim. The family, through their legal representatives, repeatedly requested documentation to prove the foundation’s claim to the photographs. Nothing conclusive was produced during this period.

What we now know is that Rune Hassner, who ran Tio Fotografer (the Ten Photographers collective and agency) in Sweden, deposited a significant portion of the Cole collection at the Hasselblad Foundation when he became its first curator in the late 1980s. In a strange twist in this Le Carré-ish story, Swedish bank SEB requested that Leslie Matlaisane – the chairperson of the Ernst Cole Family Trust – visit Stockholm in 2017. A lawyer presented him with three safe-deposit boxes of negatives, documents and papers that had supposedly been lost in a vault for more than four decades. Joe Lelyveld’s observation had been proved correct: the negatives were in Sweden.

Awkward questions

The “lost” images that Knape had built her exhibition and book on now raised awkward questions for the foundation – questions that were not simply answered by it returning 414 vintage prints and Ernest Cole’s contact sheets while Matlaisane visited Stockholm in 2017. When the Ernest Cole Family Trust asked about the return of the remaining 500 prints after the handover of the negatives in 2017, the Hasselblad Foundation refused to engage, claiming at different times that they owned the prints, had purchased the prints or that the prints had been donated to them.

The story remained shrouded in mystery. For another seven years, the Ernest Cole Family Trust continued to request the return of the collection or that the Hasselblad Foundation should demonstrate proof of purchase, proof of donation or any binding legal agreement signed by Ernest Cole. Negotiations remained frozen and the photographs remained contested. In 2022, when filmmaker Peter Chappell was doing research on Cole’s legacy for the Raoul Peck film, he discovered and connected with Rune Hassner’s partner, Birgitta Forsell, the heir to Hassner’s estate, who had also worked at the Hasselblad Centre from 1989 until 1995. Eighteen months later, James Sanders visited Forsell in Stockholm and asked her if she could throw any light on the foundation’s deadlock with the Cole family and whether she could explain how the Hasselblad Foundation acquired the images in the first place.

What could she reveal about the provenance of Cole’s work at the foundation? The statement she wrote was explosive.

“I can testify that Rune Hassner deposited the Ernest Cole photographs and personal effects, previously held at Tio Foto agency, at the Hasselblad Centre for safekeeping until such time as the material could be returned to Ernest Cole’s family in South Africa. This was intended to be a deposit, not a donation, which is confirmed by letters in the Hassner archive.” She added: “It should be noted that Tio Foto functioned as an agency for Cole while the Hasselblad Centre was a storage site. Neither Tio Foto nor the foundation… ever owned or had the right to sell or give away the Ernest Cole prints. There is no possibility that the Hasselblad Centre or the Hasselblad Foundation could have purchased any of those prints.”

The statement, which I have a copy of and which was exchanged between the family and the foundation, ends by saying that she was aware that the family had been “struggling for its rights for many years” and that it was long overdue that the Hasselblad Foundation “repatriates all the Ernest Cole prints and personal effects it still holds”. This damning information meant that the game of cat and mouse between the Hasselblad Foundation and the Cole Family Trust was over. So, too, was the narrative that the Cole negatives were “lost”, and it was now finally established that the remaining 497 Cole prints in the Hasselblad Foundation were conclusively owned by Ernest Cole himself and subsequently his family on his death.

In 2009, I was invited to give my opinion on a collection of Cole photographs at the Ethnographic Museum in Leiden. The images had been loaned by Frieda Nicolai, a Dutch diplomat who lived in South Africa from the 1990s through to the early 2000s. The provenance of the collection could be traced to Geoff Mphakati, a friend of Ernest Cole and a close associate of Nicolai. Mphakati was also a well respected township impresario. After Mphakati’s death in 2004, Nicolai took the Cole collection to Holland.

Intervention

Following the loan of the photographs to the Ethnographic Museum, lawyers representing the Ernest Cole family and an international collector, represented by Mark Sanders, intervened and the pictures were taken to The Hague where they were contested in a legal action. For two years, the pictures were held in legal limbo as Nicolai challenged the claim. In 2012, Nicolai abandoned her defence and the photographs were released by the court. The family sold some of the prints to the international collector who had paid the legal fees of the court case in The Hague.

This sale signalled two important developments: firstly, vintage Ernest Cole photographs were highly sought after in the fine art world; secondly, the family were properly paid and able to enforce their copyright around the world. Six years after the handover of the negatives in 2017, Nicolai returned a further 60 images to the Cole Family Trust. She had held on to these prints despite a court order instructing her to hand everything back to the family.

Contested collection

Closer to home there is another contested collection of Cole pictures. John Hillelson, to whom Joe Lelyveld had written so informatively in 1991, constructed a deal with the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) to sell a collection of 73 vintage prints, which he claimed were his personal property, in 2003. JAG bought the collection for £5,000 which was verified to me by the then director of Jag, Rochelle Keene. But does an agent dealing in editorial work have the right to sell a photographer’s vintage prints? Could Magnum sell Cartier-Bresson images to a collector, for example?

In an attempt to throw more light on the JAG Ernest Cole collection, Chief Curator Khwezi Gule said the issue was out of his hands and referred me to the Director of Arts, Culture and Heritage in the City of Johannesburg. At the time of going to press, the director had not replied to my question about the disputed status of their collection. They might have a licence to sell images or digital versions for editorial use, but as I understand it, they do not have the right to sell the vintage photographs without the agreement of the photographer or the photographer’s estate.

As someone who has been involved in setting up two agencies, Afrapix and South, it was understood as standard practice that copyright always belonged to the photographer. Leslie Matlaisane, nephew and chairperson of the Ernest Cole Family Trust, strongly believes that “Ernest Cole never sold his images to Hillelson. There has never been provenance of these images and due process was not followed in this interaction. It also needs to be said that the family never received any money from this sale.” Ironically, the film directed by Raoul Peck that premiered at Cannes is titled Ernest Cole: Lost and Found.

From the evidence in Joe Lelyveld’s letter and Birgitta Forsell’s statement, Cole’s negatives and prints were never really “lost”. They were in storage in Sweden. The hard question to be answered is why did it take the Hasselblad Foundation 34 years to return the prints to the Cole family? Why did it take 45 years for the negatives to be returned from the Swedish bank vault, if that is indeed the place where they were hidden.

Original Cole material

In preparation for a big exhibition of Cole’s work at Foam in Amsterdam in 2023, the gallery approached two institutions that held original Cole material to supplement the work in their show: Moderna Museet in Sweden and the Dutch National Archive (DNA). The Cole family had been in contact with Moderna Museet about their Cole holdings since 2015. Museet Moderna claimed that they owned the collection, having acquired the images following a collective exhibition organised by Tio Fotographer and Rune Hassner in 1970.

All of this is disputed by the family. The Moderna Museet has, according to the Cole Family Trust after repeated requests, provided no viable provenance that defines this Ernest Cole collection as a gift or sale.

According to Swedish journalist Toby Selander of Expression newspaper, all Rune Hassner provided in the handover of the exhibition from 1970 was an unsigned note from him that Cole accepted a donation of money for a contribution to printing costs for the exhibition, with no signature from Cole himself. It was only in 2022 that the Cole family learned of the DNA collection. The archive claimed to have inherited the images from a photographic agency that folded. But as we have seen, it is well established that agencies do not own a photographer’s prints.

Leslie Matalisane informed me that when the Cole Family Trust was asked if it would be willing to permit these images to be exhibited at Foam in June 2023, it agreed on the condition that the prints from both Moderna Museet and the DNA be returned to the Cole family after the exhibition.

No substantive proof

According to Matlaisane, both institutions refused to return the Cole images and also have failed to offer substantive proof that they “owned” the prints. So the impasse persists between the claims that these two organisations have on Cole’s work and the Cole family’s perception that they rightfully own the material.

It looks very much as if the Hasselblad Foundation saga will be replayed. With the Hasselblad Foundation experience behind him, Matlaisane of the Ernest Cole Family Trust is clear on the disputed provenance of the Moderna Museet and DNA collections: “If they can’t prove ownership, then the material must be returned to Cole Family Trust.”

In response to the latest claims by Moderna Museet, Toby Selander in a recent article in Expression newspaper, writes that the organisation was investigating the situation and would get back to him after the Swedish summer holidays.

Per Wästberg, an anti-apartheid stalwart who with the assassinated Olof Palme was a leader of the anti-apartheid struggle in Sweden, told Selander: “I absolutely think that Moderna Museet should return this like everyone else. I have had a lot of contact with the relatives and they are disappointed with how they have been treated.”

We can only hope that respected institutions such as the Moderna Museet, DNA, JAG and other repositories where Cole’s work is held but not acknowledged and where his ownership is in dispute, will “do the right thing”, as the Hasselblad Foundation eventually did.

The wave of repatriation from First World institutions back to the rightful owners in Africa exemplifies the moral imperative to return material that lacks legal provenance or was acquired through buccaneering opportunism, like the Benin Bronzes. In the last few weeks, Catherine Hlatswayo, Cole’s last direct close relative, died. It’s been an extraordinarily long wait for Cole’s family and their beneficiaries.

Let’s hope the Cole family may finally benefit from the brilliant and courageous work of their relative Ernest, even if such benefits were not available to him in his lifetime. Understanding vintage and modern prints According to hybrid art platform Artuner, a vintage print is one printed by the artist or under the artist’s close supervision shortly after they exposed and developed the negatives that the print was made from. The photography critic AD Coleman adds that a print is only vintage if it is made using “materials and procedures acceptable to the photographer who made the negative (and that) it is only one of several significant kinds of print which may be produced from that negative”.

So not only does a print have to be made by the artist or under the artist’s supervision, says Artuner, but it has to be made to their liking, using the chemicals and materials that they approve of. Vintage prints do not necessarily have to be signed by the artist, although today this can add a desirable level of assurance that the print being sold is indeed vintage. A modern print is one where “the negative that a photographer uses to create a vintage print, if stored correctly, can be used for many years to come. If reused, it will still produce the same image as the vintage print.”

The difference, of course, is that prints are made a long time after the artist has made the negative and without their supervision or the materials they may have wanted used. These are called modern prints – and in order for them to have value, they must be printed by someone who knew the photographer personally and had a sound knowledge of how they wanted their photographs to look. Instead of the artist’s signature, they have an estate stamp.”

According to the UK National Portrait Gallery, “although there is no uniform definition of a vintage print, it is considered that a vintage print is a print made close to the time at which the negative was first exposed or a print made immediately after developing a negative. Vintage prints often have a premium attached because they are considered the original piece of art, as it is possible to arbitrarily obtain many copies of the same negative. This means that photographers therefore choose to sign their vintage prints.”

Paul Weinberg is the curator of the Photography Legacy Project (plparchive.com) that enabled the digital legacy of Ernest Cole to be available online. With David Goldblatt, he also established the Ernest Cole Award for photography in SA.

This story was first published in Daily Maverick.

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.