This event is no longer the domain of older white men.

Seated in the lounge of the All-Africa Protoport (AAP), visitors have a view of lush green landscapes and futuristic transport systems and buildings. Brightly coloured models display the work of the African Conservation Effort (ACE), set up to repair the damage done to the continent’s ecoregions by former colonial powers. This fascinating installation was created by the artist Olalekan Jeyifous (Ibadan, Nigeria), who received the Silver Lion award for a promising young participant at the 2023 edition of the Architecture Biennale in Venice.

Lesley Lokko, the Ghanaian-Scottish educator, scholar and author, and the curator of the Biennale, has put together an eye-opening exhibition. The Laboratory of the Future has brought together an impressive amount of visionary creativity from sources that were hardly seen and heard in previous years. There were some complaints that there is not much architecture to be seen in this edition, but for many, this Biennale broadens the horizon far beyond expectations.

Lokko aimed to use her curatorship to bring change. The Laboratory focuses on the themes of decolonisation and decarbonisation. The gender balance of the contributors is 50-50; the average age is 43; and many of the contributors are from the African continent or have an African background. A larger architectural exhibition from Africa has not been seen in Europe before, especially not in an arena as revered as the Venice Architecture Biennale. For a long time, this was the domain of older white men. That image has been shattered.

Confronted with students’ work in African architecture schools, Lokko became increasingly disturbed by the ignorance of the local context in educational programmes, often developed from a Western perspective. In 2015, she founded the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, offering education to excellent graduates from South Africa and other parts of the continent. After a short appointment as Dean of the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture at City College of New York, she established the African Futures Institute (AFI) in Accra, Ghana in 2021. The AFI is a postgraduate school for architecture, as well as a platform for events. Her career has given her a strong sense of the promise the next generation of African architects has to offer. Her appointment as curator of the Biennale has given her the chance to show the world Africa’s creativity and agenda-setting architecture and to show policy-makers in Africa what is at stake in shaping the built (and unbuilt) environment.

Many of the presentations go far beyond what you would expect at an architecture exhibition, and some visitors might think they ended up at Venice’s contemporary art biennale, which is held on alternating years. This reflects the exploratory position that Lokko promotes, where architecture is questioning as well as is questioned in a wider range of contexts. And, as she shows by including artists like Olalekan Jeyifous, she doesn’t restrict architectural production to architects’ work alone.

The main exhibition is organised around two main locations. The Central Pavilion, amid the twenty-nine national pavilions in the Giardini, contains Force Majeure, which focuses on the architectural production of Africa that is – in parallel with the legal term – unforeseeable, external, and irresistible. The Arsenale houses Dangerous Liaisons, presenting work on the edge or across the boundaries of architecture, engaging with landscapes, ecology, policy, conflict, identity, and other fields, expanding to new territories of relevance and urgency.

Interwoven in both exhibitions are the Curator’s Special Projects and Guests from the Future, showcasing emerging and established practitioners whose work is facing the future and breaking boundaries.

Exploring both locations is truly an adventure. The most famous architects of African descent, Sir David Adjaye and Pritzker Prize-winner Francis Kéré, are presented in the Central Pavilion. Their contributions are very architectural, with large models, drawings, and scale 1:1 building parts. Mariam Kamara’s Atelier Masōmī’s poetic work is also presented in models and drawings, showing her translation of the identity and history of Niamey (Niger) into present-day architecture that addresses the ecological, economic, and cultural characteristics of its context.

Cave_bureau (Nairobi, Kenya) presents its oral-architectural practice through a performance in which connection is sought with African archives that were passed down from generation to generation through stories, songs, dance, and poetry. Their work links architecture with nature, and explores the anthropological and geological context of their projects, presenting a future that is rooted in pre-colonial history.

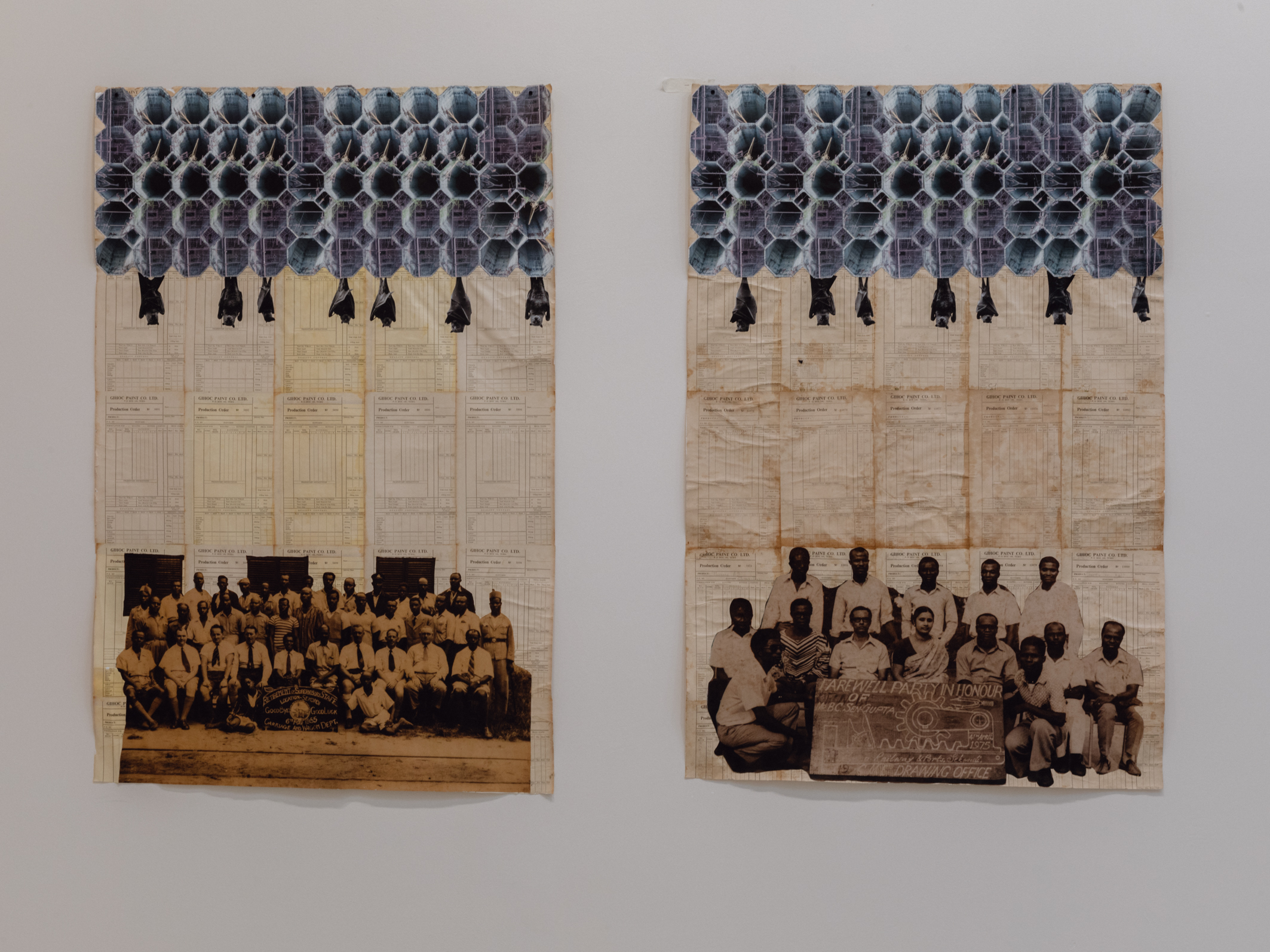

Force Majeure also includes the work of Prince Claus Award-winner Ibrahim Mahama, presenting the fascinating installation Parliament of Ghosts and the transformation of abandoned modernist buildings in his hometown Tamale. This, and several other installations by mostly young practitioners, requires time to digest, which generally proves very well spent.

The Arsenale offers a kaleidoscope of emotions, from anger and shame to surprise and amazement. A striking presentation is Synthetic Landscapes I by Stephanie Hankey, Michael Uwemedimo, and Jordan Weber, which not only addresses the eyes and ears but also the nose; visitors walk on a rammed earth floor composed of contaminated earth from the Niger Delta and engineered soils from the Midwest, resulting in a penetrating smell. The tapestry of bricks that forms part of the presentation Debris of History, Matters of Memory by Gloria Cabral and Sammy Baloji (in conversation with art historian Cécile Fromont) is of immense beauty. The wall transforms debris, mining waste, African and Indigenous motives, and Black Atlantic culture into an inclusive and regenerative showcase.

Rotterdam-based Killing Architects caused a stir with their architectural and spatial analysis of Xinjiang’s detention camps. Marked as ‘fake news’ by the Chinese diplomatic representation in Rome, the office of architect and journalist Alison Killing meticulously constructed the network of detention camps using visual and spatial methods such as satellite images, 3D modelling, and even spelling out the Chinese prison regulations as a way to overcome the almost complete closure of Xinjiang to journalists.

Serge Attukwei Clottey produced a huge tapestry made from stitched yellow plastic containers, deformed by cutting, drilling and melting, as part of his Afrogallonism project, in which global material culture is localised, with hints of Ghanaian Kente cloth. The work is installed hanging over the historical naval docks of the Gaggiandre, commenting on histories of trade and migration.

Close by, an iconic pavilion designed by Adjaye Associates gives a stage to lectures, panel discussions, performances, and storytelling. The entire structure is built up by staged timber members, the Kwaeε (which means ‘forest’ in Twi, one of the largest Ghanaian coastal languages) external structure has the shape of a triangular prism, while the internal space resembles a cave. It is an intriguing arrangement, with interesting see-throughs, shading, and smells due to the blackened timber.

The Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement awarded to the artist-designer Demas Nwoko can be seen as an exclamation mark. Although a small oeuvre, his work for over five decades – Nwoko was born in 1935, in contrast to the low average age of the other practitioners – criticises Africa’s reliance on the West for imported materials and ideas. His quote in the catalogue, originally from Wallpaper* in 2022, connects seamlessly to the Biennale themes: “If we had kept faith with how our own ancestors did it, we would have reached a certain level with sensible management of natural resources for even the Western world to learn from. They’re using far too much energy for whatever they’re achieving.”

With this Biennale, Lesley Lokko has no doubt opened the eyes of many to the talents on offer in Africa and the diaspora. As she says: “In architecture, the dominant voice has historically been a singular, exclusive voice, whose reach and power ignores huge swathes of humanity … as though we have been listening and speaking in one tongue only. The ‘story’ of architecture is therefore incomplete. Not wrong, but incomplete.”

The architectural narrative certainly is extended by this Laboratory of the Future. What more can be expected from Lokko’s African Futures Institute?

Berend van der Lans is an architect and associate of African Architecture Matters. He co-founded ArchiAfrika in 2001 and AAmatters – a non-profit consultancy working with the African built environment in the fields of heritage, planning, research, and education – in 2010.