The million dollar deals between President Paul Biya and American PR companies

In 2020, locking up opposition members and forging ballot papers is passé for dictators. A better strategy is to call in PR companies to boost the reputation of your state abroad. This investigation shows how Cameroonian President Paul Biya uses American companies for that purpose, paid for by the tax money of his own citizens.

Public relations-lobbyists do not have the best reputations. Moreover, they are not only there for ‘innocent’ companies and organisations. In exchange for hard dollars, PR agencies use their network to purify the images of dubious political regimes, be it the renewal of a military or a trade agreement, a seat in an important body, the lifting of international sanctions and so on. PR companies are a useful tool for many regimes to appear as 'normal' as possible to the outside world, as a front for what happens behind the scenes. Cameroon is one such a country working hard on its public image. Our investigation exposed the details of various contracts the Cameroonian government has entered into with public relations firms. Cameroon is by no means the only country doing this, but few dictators control the shadow play of perception and image as well as Cameroonian President Paul Biya.

Biya is 87 years old and has occupied his presidential seat for over 38 years. Under Biya’s rule, Cameroon has become a de facto dictatorship. Opposition members disappear en masse in prison. Demonstrations in the English-speaking part of the country turned into a full-blown civil war in 2017, after the president refused any form of dialogue. There, and also in the conflict with Boko Haram in the Northern Province, Cameroonian forces are systematically perpetrating atrocities against the civilian population.

These events have devoured Biya’s reputation. As a result, in February 2019, the United States reduced its military aid to Cameroon. A few months later, the country lost its privileged access to the US market, provided for under the African Growth and Opportunity Act.

These were two major setbacks for the Central African dictator. Cameroon’s international reputation was worsened when a video went viral in 2017, showing a Cameroonian woman and her baby killed by government soldiers. Later that year, Biya claimed to have won the election for the seventh time. The evidence of fraud was as overwhelming as it was shameful.

And still, ‘The United States remains a friend and partner of Cameroon’, the website of the American embassy in the Cameroonian capital Yaoundé reads.

Paul Biya understands the importance of a good relationship with the most powerful country in the world. He realises that such relationships must be maintained and massaged. He likes to leave that to American PR firms that specialise in money laundering dictators. Since 2017, at least five deals have been registered between the Cameroonian government and US PR firms:

- A 12-month contract as of August 2017 with Mercury Public Affairs worth $ 1.2 million.

- This contract overlaps with a contract to Squire Patton Boggs for $ 400 000 a year, which expired at the end of 2017.

- In mid-2018, the Glover Park Group acquired a public relations deal worth $ 600 000.

- Between July 2019 and July 2020, Clout Public Affairs signed a deal worth $ 660 000.

- In between, we see Squire Patton Boggs appearing again for a $ 400 000 contract.

All this information is publicly available on the website of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, the watchdog of foreign lobbyists of the United States Department of Justice.

As of July 2017, the total value of contracts was $ 3.26 million. Money that came from the Cameroonian taxpayer.

The resurrection of a dictator

There are also earlier examples of how US public relations lobbies laundered local affairs in Cameroon. In October 2004, there were presidential elections in Cameroon, which Paul Biya planned to win, although the dictator is struggling.

At the beginning of 2004, the US State Department reported that the Cameroonian military had committed extrajudicial killings and other atrocities.

Moreover, the Internet has now reached full penetration on the African continent. It is the first presidential election in Cameroon where social media are a factor, and information is more freely available to the general population.

Biya realises that his usual way of stealing the ballot box — locking up opposition, manipulating ballots — is too risky. Biya risks losing credit in Washington. He needs a more subtle approach. The whole perception around the election show has to change.

In July 2004, a few months before the elections, the Cameroonian dictator reinvents his image. He contacts the American firm Squire Patton Boggs and concludes a contract worth $ 400 000. The PR firm's job is to strengthen Cameroonian-American ties, including ‘election-related issues.’

One of Squire Patton Boggs's lobbyists, Greg Laughlin, brings together a group of former US Congressmen, who as independent election observers, keep an eye on election day. Biya ‘wins’ the elections with 71 percent of the vote. ‘The election was fair,’ Laughlin and his colleagues testify, a message widely distributed in the local media. ‘Voting impresses American observers, ’reads the headline of the regime-minded newspaper Cameroon Tribune on October 13.

The ex-MPs led by Laughlin had themselves, knowingly or not, been fooled by Cameroonian officials, as it turned out. They were only shown a handful of regime-prepared election rooms.

Other election observers are dumbfounded. ‘In some key areas, the election process lacks credibility,’ concluded a delegation, led by former Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark. His group visited no fewer than 263 election halls across the country. Christian Tumi, the Cardinal of Douala, is even more critical: ‘Like all elections, these elections are also rife with fraud.’ But the damage has been done: it is Laughlin's testimony that resonates.

How do you steal elections?

In the information age, Biya understands that public image means everything. It hardly matters to the international community that you steal elections. How you steal them is much more important.

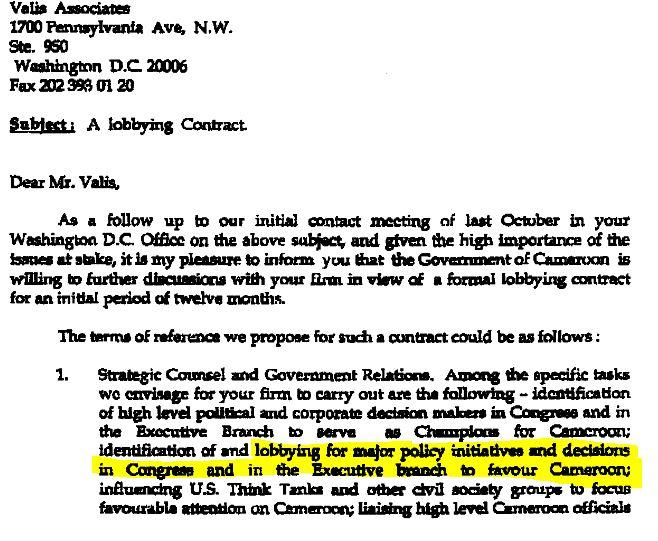

A month after the elections, Biya signs a $ 150 000 contract with Richard Schulze, lobbyist of the PR firm Valis Asociates and Greg Laughlin's co-observer during the elections. The assignment: ‘Maximize the impact of Cameroonian political and economic reforms in the US administration.’

Many PR firms will follow over the years. The more dire Biya's situation, the more he calls on the Americans to clear his image. It is therefore not surprising that the number of contracts increases significantly, in particular after 2017, a year before the next presidential elections and at the start of the war in the English-speaking part of the country.

Fake news in Cameroon

Public relations have cost President Biya millions of dollars. In the run-up to the October 2018 elections, a number of channels are set up on social media that are remarkably one-sided. They blame every violent incident on separatists, without highlighting the role of the Cameroonian army.

For example, we find: @CameroonTruth (founded in August 2018):

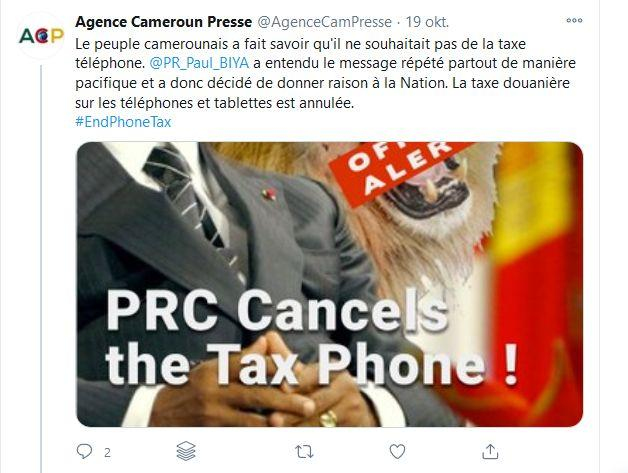

And also @AgenceCamPresse, part of the ‘press agency’ Agence Cameroun Presse, founded in July 2018:

Agence Cameroun Presse, is especially interesting. Their goal, according to their website, is to bring ‘the facts and real news about Cameroon.’

In the aftermath of the 2018 elections, foreign observers appear on national television reporting that they have been sent by international NGO, Transparency International, to monitor the elections. They report that the election process was conducted in all fairness.

Transparency International is quick to react stating that they have not sent any observers to Cameroon and that they have no affiliation with the so-called observers. The organisation strongly objects against to the misuse of its name. Michael Hornsby, head of communication at Transparency International, personally confirms this in an email in 2018, stating: ‘It seems [the observers] were invited by Agence Cameroun Presse.’

The so-called ‘observers’ turn out to be a mixed bag of petty thieves, gardeners and unemployed people. None have any experience with monitoring electoral processes, and lacks any understanding of African affairs. Among them Nurit Greenger, who declares on Twitter on October 9, 2018 that she had been invited by both Agence Cameroun Presse (ACP) and Transparency International.

In July 2018, at the time of the founding of the 'press agency' ACP, two public relations contracts with the Cameroonian government were running: Mercury Public Affairs (worth $ 1.2 million) and Squire Patton Boggs (400,000 dollar). Both contracts explicitly state their objective as ‘improving the image of Cameroon in the United States’.

Is it a coincidence that, as in 2004, the Biya regime uses false statements from seemingly independent foreigners to give credibility to his re-election? Is it possible that the ‘observers’ or their clients did unpaid work? Unlikely as it may be, at the time of writing we were unable to establish a more direct link between Agence Cameroun Presse and Squire Patton Boggs of Mercury Public Affairs.

No amateurism

Elsewhere, we find explicit examples of how American PR firms use fake news to tilt public opinion — and with it the Washington legislature.

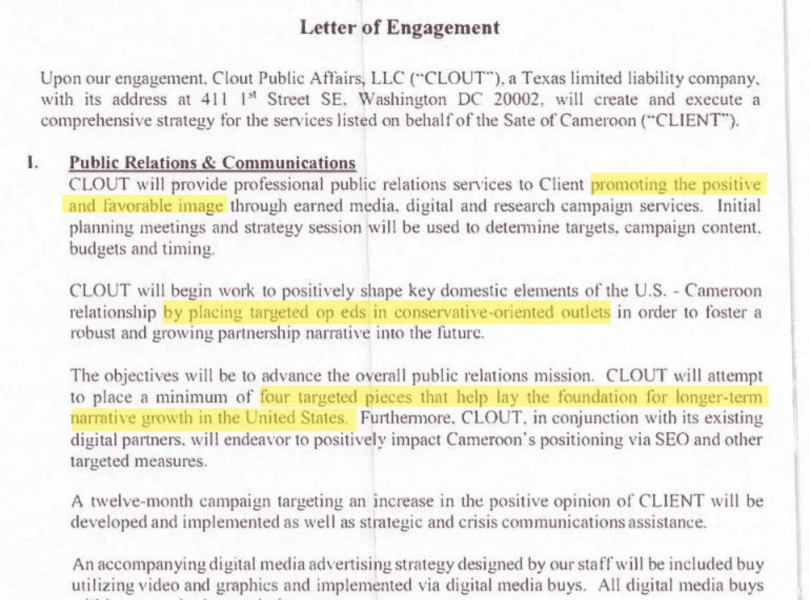

We investigated a contract between the Cameroonian government and the American PR firm Clout Public Affairs. The contract, signed on July 2, 2019, states that the company will ‘provide professional PR services to put Cameroon in a positive and favorable light.’ This will be done by ‘posting at least four articles in conservative-oriented news sites.’ These articles should form the basis for a ‘robust partnership in the future.’

In other words, these fake or questionable news items should promote a more positive image of Cameroon in the United States. The price for those services? Four such messages per month at $ 55 000, excluding costs.

We found an example of one such an article. On December 18, 2019, just before Christmas, Clout Public Affairs tries to strike a chord with God-fearing America. The lobbyists write a newspaper report headlined, ‘Boko Haram terror group continues to persecute Christians.’

The story opens with a brutal murder of an unidentified ‘Christian boy’ in Cameroon. Furthermore, the article almost casually urges readers to ‘recognize the importance of countries like Nigeria and Cameroon … because of America's commitment to the persecuted worldwide and our fight against fundamentalism.’

And for those who doubt whether the persecuted belong to the right faith: ‘The vast majority of the 200 000 refugees in Cameroon are Christians.’ That is not true. In the northern regions of Cameroon, where Boko Haram operates, the majority of the population is Muslim.

Furthermore, the article condemns the policy of the US Democrats, ‘who condemn Cameroonian leadership rather than the attacks of Boko Haram.’

The Clout Public Affairs article appeared in an abbreviated version on Hispolitica, that claims to be ‘a national website about political problems that concern not only Hispanics but all Americans.’ There is no reference to Clout Public Affairs. But plagiarism isn't the only misstep committed here.

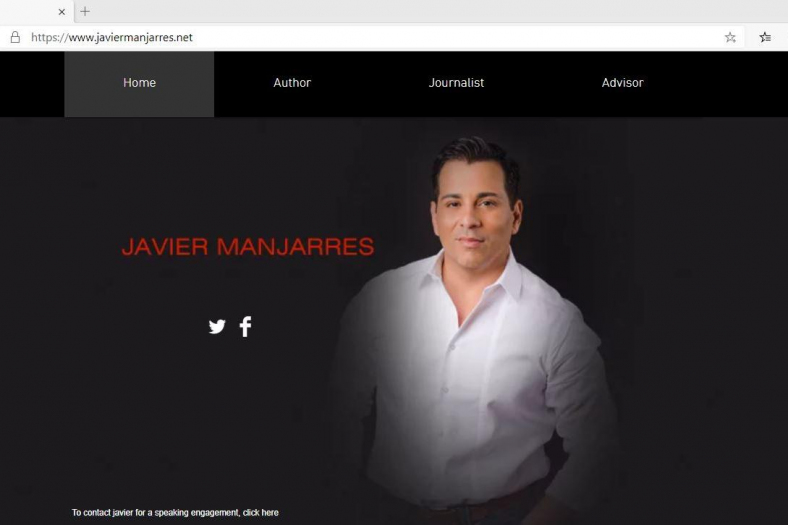

The Hispolitica website seems to date from the 1990s. They still have articles from 2017 on the homepage. Their Twitter account has a total of 102 followers. Owner of Hispolitica, according to his personal website, is Mr Javier Manjarres, a naturalised American Colombian. He manages more ‘news’ websites through his company Diverse New Media, including The Floridian and CactusPolitics. They are all uncredible sites with some local news and hardly any followers on social media.

There is clearly more to this than plagiarism and amateurism. Manjarres has too many contacts in high circles. On Facebook he poses in a photograph with Donald Trump. Marco Rubio, the Republican Senator from Florida, also seems to know him personally, as does Republican Ted Cruz.

And then the world suddenly becomes very small. The current CEO of Clout Public Affairs is David Polyansky, who worked until 2018 as campaign manager for Ted Cruz. And Clout’s managing director is Matthew Whitaker, former Secretary of Justice under Donald Trump. It is clear — Clout Public Affairs has connections at the highest level.

On December 16, 2019, a post on the CactusPolitics website reads: ‘How the Trump administration scored a peace deal in Africa.’ The author is Javier Manjarres, who again makes no connection whatsoever to Clout Public Affairs.

The article is nonetheless an exact copy of the text that Clout Public Affairs officially submitted to the American lobby watchdog on December 17, 2019, proving the connection between Clout Public Affairs and Javier Manjarres. This is also evident from the open database of the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks money flows in the politics of the United States.

News for ‘the right legislators’

There are uncertainties surrounding the position and work of Javier Manjarres. What are all the articles about Cameroon doing on a website about local news from Arizona and Florida? What does Manjarres get from Clout Public Affairs in return for publishing these articles? And why does Clout Public Affairs go to such lengths to publish something on a website with only 34 followers on Twitter?

I called on Manjarres to raise these questions. He acknowledges the existence of Clout Public Affairs, and also that he regularly copies articles from it. He, however, denies that he gets any money for doing so. Manjarres claims to know and respect journalistic ethics. The reason he published the articles is that Marco Rubio (the Republican Senator from Florida) had spoken out about Cameroon, he claims. ‘That makes it newsworthy in Florida, and so I publish it,’ he says. Further on in the conversation, it seems that his websites do not rely on social media. ‘"We mainly target email for distribution,’ he says, adding that ‘It's especially important that the right legislators read us’.

In other words, these websites have no ambition at all to inform a broad audience. They merely serve to weigh on policy.

There is no hard evidence that Manjarres took money from Clout Public Affairs to publish the articles. He himself strongly denies this. In fact, during the telephone conversation, Manjarres claims to know nothing about the $ 55 000 that Clout Public Affairs receives from the Cameroonian government every month. ‘I will contact them about this,’ he says dryly.

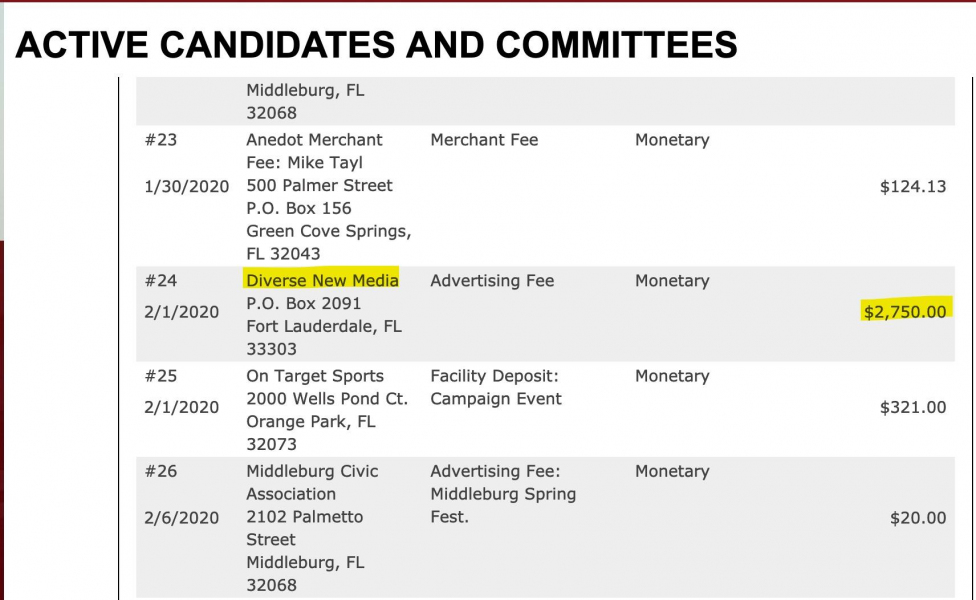

After further research, when we look into the spending of political candidates in Clay County, Texas, we find that Manjarres received $ 2 750 through his company Diverse New Media for ‘advertising’ from Mike Taylor, sheriff-candidate for the Republicans.

In the news report Manjarres wrote for Mike Taylor, he accuses another sheriff-candidate of harassment and an illegal arrest. The story turned out to be incorrect, but the requested corrections were never made.

In Florida, Manjarres is indeed known as a pay-to-play blogger. In other words, he writes about anything, as long as you pay him.

Influence and networks are more difficult to measure than money.

A look at Manjarres' criminal record doesn't help his reputation: attempted murder (in 2016, he attacked his sister's boyfriend and his pickup truck in a Florida parking lot), domestic violence, burglary with violence.

How plausible is Manjarres' explanation? Was he used by Clout Public Affairs or did he get money? I ask Anna Massoglia, who is a researcher at the Center for Responsive Politics in Washington. As the name suggests, this institution investigates transparency in democratic societies.

Massoglia doesn’t know the specific case of Manjarres, but is well aware of the activities of said PR companies. ‘It’s possible that Manjarres didn’t receive money from Clout. But what counts, of course, is not money, but influence and networks — those are more difficult to measure.’

Double screwed

There is another remarkable thing about the four pieces a month that Clout Public Affairs promised to write for the Cameroonian government: they are not just about Cameroon. Often they have a pro-Trump phrase. Prominent members of the Democratic Party are regularly defamed.

This is no coincidence. Several of the public relations companies mentioned are run by people linked to politicians from ultra-conservative, Republican circles. David Polyansky, the ex-campaign chief of the prominent Republican Ted Cruz, is one example.

Take the article Manjarres published in late 2019, ‘How the Trump Administration Scored a Peace Deal in Africa.’ It opens with a reference to the Democratic Party's attempt to oust Trump, calling it ‘wanting to undo an election result.’ Farther on, Trump is hailed as a broker for a so-called ‘diplomatic gain’ in Cameroon, and the Obama administration and US Senator Karen Bass are successively vilified.

Manjarres' article not only serves Cameroonian interests, it is primarily a defamatory opinion piece on American domestic politics. And, to be clear, this article was written and registered by Clout Public Affairs as part of the deal with the Cameroonian government, and paid for by the Cameroonian taxpayer.

Cameroonians are not only money laundering their dictator’s wealth in the most powerful country in the world, but they are also funding the spread of conservative propaganda in the United States.

Clout Public Affairs propagates its own political agenda, while at the same time being lavishly paid for it by the poorest people in the world.

The PR firms involved, including Clout Public Affairs, refused to respond after several requests.

There is hardly any opposition to the activities of the companies involved. In one case, Cameroonian-American attorney Jiggi Tah filed a lawsuit in a US court against the Cameroonian government. Tah lost the case due to inadequate evidence. He responds electronically from Delaware in the US: ‘Such companies indirectly encourage human rights violations. The purpose of this lawsuit was to show that the contracts are unconstitutional. Once that is done, we can reclaim the millions paid out’.

This article was first published in Dutch by MO*