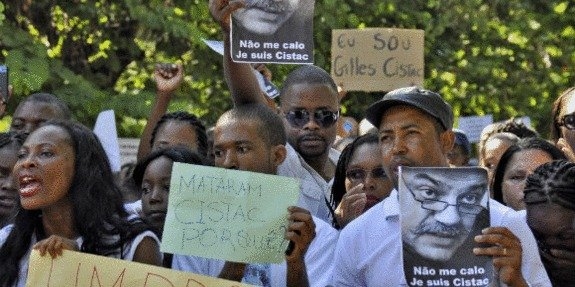

Was Mozambican constitutional lawyer Gilles Cistac murdered because of ideas that upset the country’s ruling Frelimo party? Listening to Frelimo’s vehement denials and silly remarks about how the real motive for the murder could have been to ‘make Frelimo look bad’ one would almost conclude that that’s probable.

Those who have studied the Mozambican state’s descent into criminality, however, have a slightly different take on the assassination of the much respected French-Mozambican lawyer who advised Frelimo on constitutional matters. The mafia-style killing of Cistac, in broad daylight in front of a Maputo café, may have more to do with organised plunderers feeling threatened than with suppression of ideas.

Daily Maverick’s correspondent Mercedes Sayagues, a veteran reporter resident in Mozambique, places the murder squarely in a series that started with the shooting of journalist Carlos Cardoso in 2000. Cardoso was investigating fraud in the Mozambican Central Bank, a massive looting operation that involved the son of then president Chissano. In 2010, Sayagues writes, a customs official who was investigating tax evasion and illegal diamond dealing was shot ‘mafia-style’. A year later it was the turn of a nature reserve manager who happened to do much of his work close to a stolen cars transit route near the South African border. Then a number of rich businessmen suspected of involvement in drug deals were shot. And then a judge who was about to rule on a set of kidnappings of business people. Other murders have taken place within rhino-horn and ivory-smuggling syndicates.

Lawyer Gilles Cistac was advising the new president of Mozambique, Filipe Nyusi, on provincial autonomous powers. He happened to agree with the opposition that provinces should have such greater powers. This may indeed have gotten him killed –but not because the idea itself was unsavoury to the gangsters that control much of the country’s economy nowadays. Provincial powers come with a lot of money, especially now that gas and coal reserves are being mined in Renamo’s strongholds in the north and centre of the country. “If these resources were to be managed by autonomous provinces rather than the central government, (…) Frelimo political elites with linkages to the energy sector would suddenly have to share,” writes Anne Pitcher, professor of African studies and political science at the University of Michigan, US on the website Africa is a country.