Among African writers, opinion makers and activists the news of the Charlie Hebdo attack has provoked an outpour of anger: at the attack itself, but perhaps even more so at the twin scourges of terrorism and dictatorial oppression suffered by people in Nigeria, Somalia, Cameroon, Kenya, Mali and elsewhere on the continent. The ones who attracted most fire were African leaders who had the gall to march in Paris, whilst seemingly not bothered about victims of terrorism back home.

The internet buzzed African fury particularly at Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan, who sent a “Je suis Charlie” message of support to France, whilst hundreds of peasant families in his own country were being slaughtered by the Islamist-extremist Boko Haram army. On that act of terrorism and others, -like the bombings of markets in two other Nigerian towns-, as on the atrocious behaviour of the Nigerian army, which continuously drives more youth in the north into the Boko Haram fold, Jonathan has stayed mum. “The contrast between the attacks in Paris and the (attacks by Boko Haram) reveals the ravages of state failure,” posted Ugandan commentator Grace Nataabalo Adyeeri, noting that the Nigerian president happily campaigns for re-election without uttering a word about the thousands of terror victims in his country.

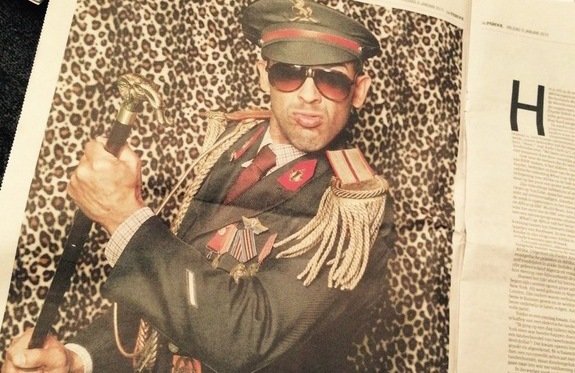

Picture: Nigerian-Dutch satirist Ikenna Azuike feels it's his duty to provoke. His What's Up, Africa? blog will be broadcast by BBC World News every Friday night. For more information check www.facebook.com/whatsupafrica. Picture was published in Amsterdam-based newspaper Het Parool on 9 December 2015.

On the South African Mail & Guardian’s Africa site, Lee Mwiti criticised the way the ‘War on Terror’ is interpreted by leaders such as Jonathan, who seem to think that cementing the own governments’ power and clamping down on opposition is the way to go. “In nearly all the six (African) countries at the Paris rally, executives continue to consolidate power; marches and protests are either banned or clamped down upon, judiciaries wilfully weakened and media outlets either suspended or legislated out of existence.” This, Mwiti writes, ‘politicises’ terror, whereby the ‘security of citizens is subjugated’ –often, with little free speech left.

Many African activists also criticised perceived ‘double standards’ in what is called terrorism and what isn’t, commemorating bombings of hotels and media outlets by the US and Israel in Iraq and Palestine and pointing at Kenya’s current police death squads. Nigerian author Teju Cole also problematised the global ‘pro-free-speech’ movement’s exclusive focus on Islamic-extremist censorship, mentioning many instances where western journalists and whistle blowers have been silenced by their own governments, as well as the case of US ally Saudi Arabia’s flogging of a critical blogger.

However, there was also praise for the way the French police was able to chase and apprehend the perpetrators in Paris. “Wish we would see such swift action in our country”, said a blogger from Kenya. This put the ball again straight in the African government’s court: there is clearly a terror threat to fight, so why don’t they fight it properly? In the words of Mail & Guardian’s Lee Mwiti: “small focused steps have infinitely bigger results than the latest weapons from the West -fight corruption, share resources equitably, implement existing laws, end marginalisation.” If the African input on this issue on social media is anything to go by, this is a lesson many of the continent’s leaders have yet to learn.