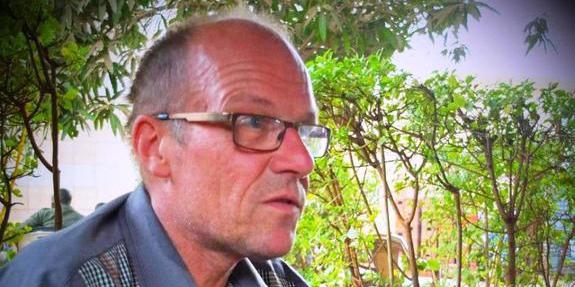

Bram Posthumus is an independent journalist who lives and works in West Africa. He recently experienced the failure of UN peacekeepers in Mali and reports that this has added to his now twenty-year long frustration with UN ‘peace-keeping-but-not-really’ in conflict zones like Angola and Ivory Coast. “It always goes wrong. If they can’t do it differently, they should just stop.”

Shouldn’t we have more UN peacekeeping, rather than less? Critics always complain that the UN is not doing enough. Rwanda is the most tragic case so far.

They usually enter a country with a military force that has little authority, plus a massive civilian bureaucracy that does many things that are not in the peacekeeping mandate. As long as that remains the pattern, we should rather not have their operations at all. For example, the UN operation in Mali has a clear mandate to stabilise key population centres and help re-establish state authority in the entire country. They had the chance to do that, last May in Kidal, an important town under rebel control. Instead, they did nothing and armed rebels killed fifty Malian soldiers. Shortly after that, a suicide attack killed four peace keepers. Malians are bewildered by this inaction.

But why conclude that ‘not enough’ is the same as ‘wrong’? Maybe they should just have sent more soldiers? Like France did in 2013?

Indeed, then the French did what was needed. They did it on their own, at the request of the Malian interim government and without the UN. For that Malians have been very grateful. It shows that quick professional operations can work.

And the UN peace keepers just don’t do that?

The soldiers never seem to have a mandate to fence in the troublemakers in the area. At least, that is how the mandate gets read. The pattern is one of remaining at a safe distance. So if there is no clear peace keeping, especially when it really matters – as it did in Kidal – the UN presence only creates more trouble for the country.

What trouble is that exactly?

You get seven thousand, eight thousand individuals who all need homes and offices and services, invading a country with a very small or fragile economy. The first thing that happens is that the rent goes up for everybody. Then prices go up because they start importing consumer goods. But most important of all, the peacekeeping operation partners with an elite of corrupt, totally discredited political leaders, none of whom contribute anything tangible. And in the meantime, the Malian state has come crashing down.

And that will drive ordinary Malians into the arms of the rebels?

There is some danger of that. It’s not that Malians like the Islamic jihadists; they don’t. They love music too much. And Malian women, especially Touareg women, are not going to be told that they must stay at home; some Touareg women have come out to say: ‘They must kill us first.’ Hundreds of thousands have fled the areas where jihadis now rule. But even these rebel groups are able to provide a semblance of law and order, routine, and even services. People also desperately need an authority that seems concerned about their needs. That authority is not the Malian state. The Malian state has disintegrated. You see that most clearly in the North, which has been overrun by drug crime and other mafias from the early 2000s.

So there is a need for massive state building?

First and foremost, the country needs security of its territory. People need to feel safe. Then comes the job of the state to provide rule of law, basic service like water, and such things.

Not easy, with so much chaos and so many rebel groups, drug traffickers, syndicates roaming free.

That is why effective military action should be combined with diplomacy and expertise on the ground. Why not engage with the Economic Community of West African States, ECOWAS, for example? That has been the most successful regional diplomatic entity on the continent so far; they prevented Guinea from tumbling into civil war. ECOWAS may suffer from its own bureaucracy, nepotism and opacity, but the ‘international community’ could still learn something. It is the learning that is always so painfully absent with the UN. They don’t listen to locals, they don’t listen to their own military advisers, they always come with this one-size-fits-all approach. And then they lie, pretending things are going well. Follow their Twitter account and weep.

Are there people inside Mali who know what needs to be done and how?

Yes, and none of the outside forces are listening. Civil society is asking for support to help address the rotten political system, the corrupt elite and the total lack of transparency and information. But the ‘international community’ doesn’t even make an effort to inform the population of what is going on and who is doing what. The UN, the French, the Americans and the development aid machinery communicate only with the corrupt top layer. They are ‘development partners’…

Wait. The French are still there?

Yes, and now they are not helping to rein in the troublemakers, but just adding to the bureaucracy. Combined with the lack of information in the country, this gives rise to a lot of suspicions and conspiracy theories –about France being after mineral resources only and so on-, and a feeling of abandonment and hurt.

Could it be true what the conspiracy theorists say, that the West is only interested in Mali’s mineral resources and not in genuine assistance?

Here, I’d like to offer a quote that is often attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte: never ascribe to malice that which can be explained by incompetence.

This interview was conducted by Evelyn Groenink, ZAM Chronicle’s investigations editor.