The use of Marxist-inspired arguments, often distorted, to support racist or nationalist political positions, is known as "rossobrunismo" (red-brownism) in Italy.

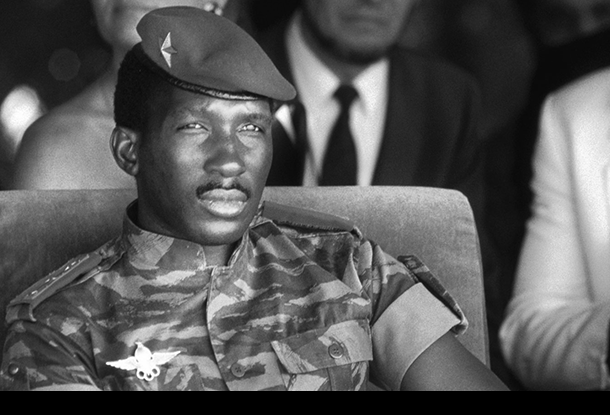

Those following immigration politics in Europe, especially Italy, may have noticed the appropriation of the words of Marxist and anti-imperialist heroes and intellectuals by the new nationalist and racist right to support their xenophobic or nationalist arguments. From Samora Machel (Mozambican independence leader), Thomas Sankara (Burkinabe revolutionary), Che Guevara, Simone Weil (a French philosopher influenced by Marxism and anarchism), to Italian figures like Sandro Pertini an anti-fascist partisan during World War II, later leader of the Socialist Party and president of the Italian republic in the 1980s, or Pier Paolo Pasolini (influential communist intellectual).

The use of Marxist-inspired arguments, often distorted or decontextualized, to support racist, traditionalist or nationalist political positions, is referred to as rossobrunismo (red-brownism) in Italy. In Italy it got so bad, that a group of writers—some gathered in Wu Ming collective —made it their work to debunk these attempts. They found, for example, that a sentence shared on several nationalist online pages and profiles—attributed to Samora Machel—that condemned immigration as a colonial and capitalist tool to weaken African societies, was fake news.

It also contaminated political debate beyond the internet: During his electoral campaign, Matteo Salvini, leader of the anti-immigration party Lega and current minister for internal affairs in Italy’s government, explicitly mentioned the Marxist concept of “reserve army of labor” to frame the ongoing migration across the Mediterranean as a big conspiracy to import cheap labor from Africa and weaken Italy’s white working class. As for who benefits from cheap, imported labor (as Afro-Italian activists Yvan Sagnet and Aboubakar Soumahoro have pointed out), Salvini says very little.

The typical representative of red-brownism is Diego Fusaro, a philosopher who first became known, about a decade ago, for a book on the revival of Marxism in contemporary political thought. More recently, he promoted through his social media profiles and collaborations with far-right webzines like Il Primato Nazionale (published by neo-fascist party Casa Pound), a confused version of an anti-capitalist critique aggressively targeting not only the liberal left, but also feminist, LGBT, anti-racist activists and pro-migrant organizations. Fusaro has theorized that immigration is part of a “process of third-worldization” of Europe, where “masses of new slaves willing to do anything in order to exist, and lacking class consciousness and any memory of social rights” are deported from Africa. As if collective action, social movements and class-based politics never existed south of the Sahara.

Yet, the appropriation of pan-Africanist thinkers and politicians like Machel and Sankara brings this kind of manipulation to a more paradoxical level. What could motivate the supporters of a xenophobic party, whose representatives have in the past advocated ethnic cleansing, used racial slurs against a black Italian government minister, or campaigned for the defense of the “white race,” to corroborate their anti-immigration stance through (often false) quotations by Machel or Sankara?

To make this sense of this, it is useful to consider the trajectory of Kemi Seba, a Franco-Beninese activist who has sparked controversies in the French-speaking world for quite some time, and has only recently started to be quoted in Italian online discussions and blogs.

Initially associated with the French branch of the American Nation of Islam, Kemi Seba has been active since the early 2000s in different social movements and his own associations, all positioned across the spectrum of radical Afrocentrism. In the polarized French debate, traditionally wary of even moderate expressions of identity politics, Kemi Seba’s radical statements predictably created public outcry and earned him the accusations of racial hatred—for which he has been repeatedly found guilty. An advocate of racial separatism (or ethno-differentialisme, as he defined it), he has quoted among his sources Senegalese historian Cheikh Anta Diop, from whom he took inspiration for his “kemetic” ideology claiming a black heritage for ancient Egyptian culture, and Marcus Garvey, whose ideas he reformulated in his call for all the black people living in France and in Europe to return to the African motherland—while classifying those remaining as “traitors.”

While one would expect white oppressors to be his main target, Kemi Seba’s vehement attacks have often been directed toward other black activists and personalities living in France, accusing them of promoting integration or collaborating with the white system (and often qualifying them as macaques, monkeys, or as nègres-alibis, “negroes-alibis”). In recent years, however, he has declared he would abandon his initial supremacist positions to embrace a broader pan-African stance, and moved his main residence first to Senegal, later to Benin. Now addressing a predominantly West African audience, he has co-opted personalities, such as the late Burkinabé president and revolutionary Thomas Sankara—still the most powerful political reference for the youth in Francophone Africa—among his claimed sources of inspiration. He has also endorsed the struggle against the CFA France—an ongoing critical reflection that was started by the work of economists such as Ndongo Samba Sylla and Kako Nubupko, well before Seba started campaigning about the issue. In August 2017, he burned a CFA banknote in public in Dakar—an illegal act under the Senegalese law—and was briefly detained before being deported from the country. The ambiguous relationship between Kemi Seba’s ideology and the far right has a long history, especially in France. Understandably, his initial racial separatism and his call for a voluntary repatriation of all blacks to Africa constituted an appealing counterpart for French white racists committed to fight the possibility of a multiracial and multicultural France. Kemi Seba, on his side, repeatedly hinted at possible collaborations with white nationalists: in 2007, he declared:

“My dream is to see whites, Arabs and Asians organizing themselves to defend their own identity. We fight against all those monkeys (macaques) who betray their origins. (…) Nationalists are the only whites I like. They don’t want us, and we don’t want them.”

Some years later, in 2012, commenting the electoral growth of Greek neo-nazi party Golden Dawn in a radio program, he argued:

“I want people to understand that today there is nothing to win by remaining in France, and everything to win by remaining in Africa. And the best solution for this… unfortunately, black people only awaken when they realize that they are in danger, when they are slapped in the face. (…) Black people are unfortunately slow on the uptake, they understand only when there is bestiality, brutality. So, maybe, if we had a movement similar to Greece’s Golden Dawn, established in France, and if they threw black people in the sea, if they raped some, then maybe someone would understand that it is not so nice to remain in France and would return to their fucking country, to their motherland the African continent.”

His supporters later qualified his statements as simple provocations, but Seba continued to be a favorite guest and interlocutor for far-right groups. For example, the webzine Egalité et Reconciliation, founded by Alain Soral—a well-known personality of French red-brownism who shifted from his juvenile communist engagement to later support for Front National and has been condemned for homophobic and anti-Semitic statements—has often provided a platform for Seba’s declarations. In 2006, Seba praised young white nationalist activists in a long interview with Novopress, an online publication by Bloc Identitaire. The latter is a white nationalist movement which works to popularize the conspiracy theory of the “great replacement”—an alleged plan of “reverse colonialism” to replace demographically the white majority in Europe with non-white migrants and which inspired white ultra-nationalists in the US. Bloc Identitaire recently formed extra-legal patrols in order to stop asylum seekers from crossing the border between Italy and France.

In 2008, Seba’s association organized a tiny demonstration against French military presence abroad with Droite Socialiste, a small group whose members were later involved in shootings and found guilty of illegal possession of weapons and explosive material. Their hideout was also full of Adolf Hitler’s books and other neo-Nazi propaganda. Relatively unknown until recently on the other side of the Alps, Seba has made his appearance on Italian websites and Facebook profiles in recent months. Since Lega’s promotion to national government in coalition with the Five Star Movement, the country has become the avant-garde of an attempt to connect different reactionary political projects—rossobrunismo, anti-EU and anti-global sovranismo (nationalism), white nationalism, neo-Fascism and others—and has attracted the attention of globally known ideologues, such as Trump’s former counselor Steve Bannon and pro-Putin populist philosopher Alexander Dugin (who, not by chance, organized a meeting with Seba in December 2017). Small webzines like Oltre la Linea and L’Intellettuale Dissidente, which following Dugin’s example mix pro-Putin positions with an anti-liberal critique and traditionalist nostalgia, inspiring attacks against feminism, anti-racism and “immigrationism.” Collectively, they have dedicated space to Seba’s ideas and interviewed him, profiting from his visit to Rome in July 2018.

Invited by a group of supporters in Italy, Seba visited a center hosting asylum seekers and gave a speech where, amidst launching broadsides against the EU and African elites who are impoverishing Africa (thus forcing young people to try their luck as migrants in Europe), he slipped in a peculiar endorsement to Italy’s xenophobic minister of internal affairs:

“Matteo Salvini [he then asked people in the audience who started booing when they heard the name to let him finish] defends his people, but he should know that we will defend our people too!”

He repeated this sentiment in an interview published later on a nationalist blog. Seba basically endorsed the ongoing anti-NGO campaign voiced by representatives of the Italian government. The interviewer suggested to Seba:

“Salvini’s battle against boats owned by NGOs, which transport migrants from Lybian shores to Italian harbors, sometimes funded by Soros’ Open Society, reflects your [Kemi Seba’s] same struggles for the emancipation from those Western humanitarian associations that operate in the African continent and enclose you all in a permanent state of psychological and moral submission.”

“Yes, I realize this very well, we have the same problem,” replied Seba.

Attacks against the NGOs organizing rescue operations in the Mediterranean have multiplied in the Italian political debate since last year. The Five Star Movement started a campaign against what they called the “sea taxis” and the previous government tried to force them to sign a code of conduct imposing the presence of police personnel on their boats. NGOs have been alternatively accused of complicity with Libyan smugglers (but neither the investigation of a parliamentary committee, nor judges in different Sicilian courts, could find evidence for this allegation).

More broadly, a dysfunctional regime governing migration flows, and the bungled reception of asylum seekers, allows such positions to take root in the Italian political sphere. What is often obscured, though, is that such a dysfunctional regime was originated by the restrictive policies of the Italian government and the European Union, through the abandonment of a state-sponsored rescue program and the externalization of border control to Libya (where media reported the dehumanizing treatment reserved to Sub-Saharan migrants) and other third countries.

Echoing Seba, Italian right-wing bloggers and opinion-makers make increasing use of anti-imperialist quotations—for example, by Thomas Sankara—to fuel this anti-NGO backlash and denounce the plundering of Africa’s wealth and resources by multinational corporations in consort with venal governments, abetted by the development industry. By the right’s bizarre logic, stopping migration flows to Europe would be a part of the same coordinated strategy to reverse Africa’s impoverishment by Europe. This use not only overlooks the fact that African migration to Europe is a tiny portion of the massive migration flows taking place across the whole planet, but also that intra-African migration is significantly more common.

It also distorts Thomas Sankara’s critical views of development, which he formulated at a time when aid mainly consisted of bilateral contributions and loans from international financial institutions, rather than NGO-sponsored interventions. And, ultimately, it generates confusion between the critique of the classical development sector—which is fundamental and has been developed for a long time by dependency theory and other schools of critical scholarship—and an analysis of the rescue sector: indeed, most NGOs currently operating in the Mediterranean are associations created in the last few years with the explicit goal of reducing mortality along the Libyan or the Aegean routes. They have never participated in development projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

What would Samora Machel and Thomas Sankara think today of the so-called “refugee crisis” and of the populist and xenophobic reactions it has provoked all over Europe? White nationalists think that they would be on their side. But what we know from their writings is that their revolutionary politics was never based on an exclusionary form of nationalism, let alone on racial separatism. Rather, it was associated with an analysis of the production of material inequalities and exploitation at the global level, and with class-based internationalism.

This is clearly articulated in many speeches pronounced by Sankara, for example in his frequently quoted intervention on foreign debt at the African Union summit in July 1987 (a few months before he was murdered), where he declared that “by refusing to pay, we d not adopt a bellicose attitude, but rather a fraternal attitude to speak the truth. After all, popular masses in Europe are not opposed to popular masses in Africa: those who want to exploit Africa are the same who exploit Europe. We have a common enemy.”

While many representatives of red-brownism and the new right would probably declare that they subscribe to this principle on paper, most of them are currently engaged in defusing any possibility of a class-based critique of capitalism, to which they prefer sovranismo and its emphasis on renewed national sovereignties. Furthermore, they are more or less directly legitimizing the action of a government that capitalizes on the anxieties of the white majority and of the impoverishment of middle and lower classes, building a consensus around xenophobia, racial discrimination and policies of strict border control, no matter the consequences. The creative use, made by the African youth, of Sankara’s thought in reclaiming and obtaining political change, such as in the Burkinabe revolution in 2014, is a demonstration of the legacy of his thinking as an effective tool for emancipatory struggles—a precious legacy that anti-racists should protect from the re-appropriation and manipulation attempted by the European racist right.

Cristiano Lanzano is a Senior Researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute.

This article was first published by Africa is a Country.