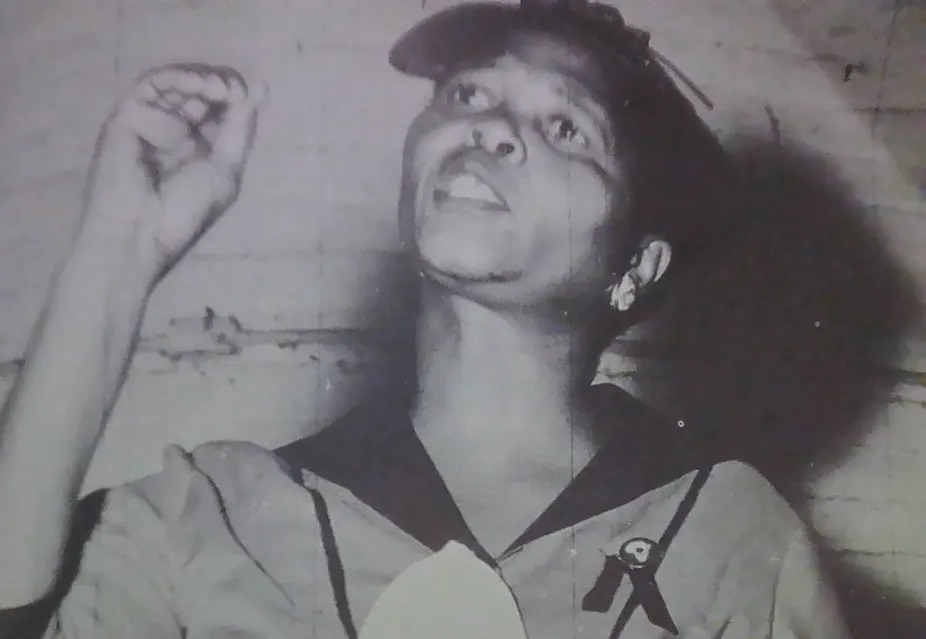

Despite her key role in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, details about Lilian Ngoyi’s life remain sparse. The short paragraphs on her legacy repeat a few well-worn phrases. South Africa’s “mother of the black resistance”, a widow and rumoured lover of Nelson Mandela, and the first woman member of the national executive committee – the core leadership of the African National Congress (ANC), the resistance movement that would later become the government of a democratic South Africa. She was also, of course, one of the leaders of the country’s famous Women’s March.

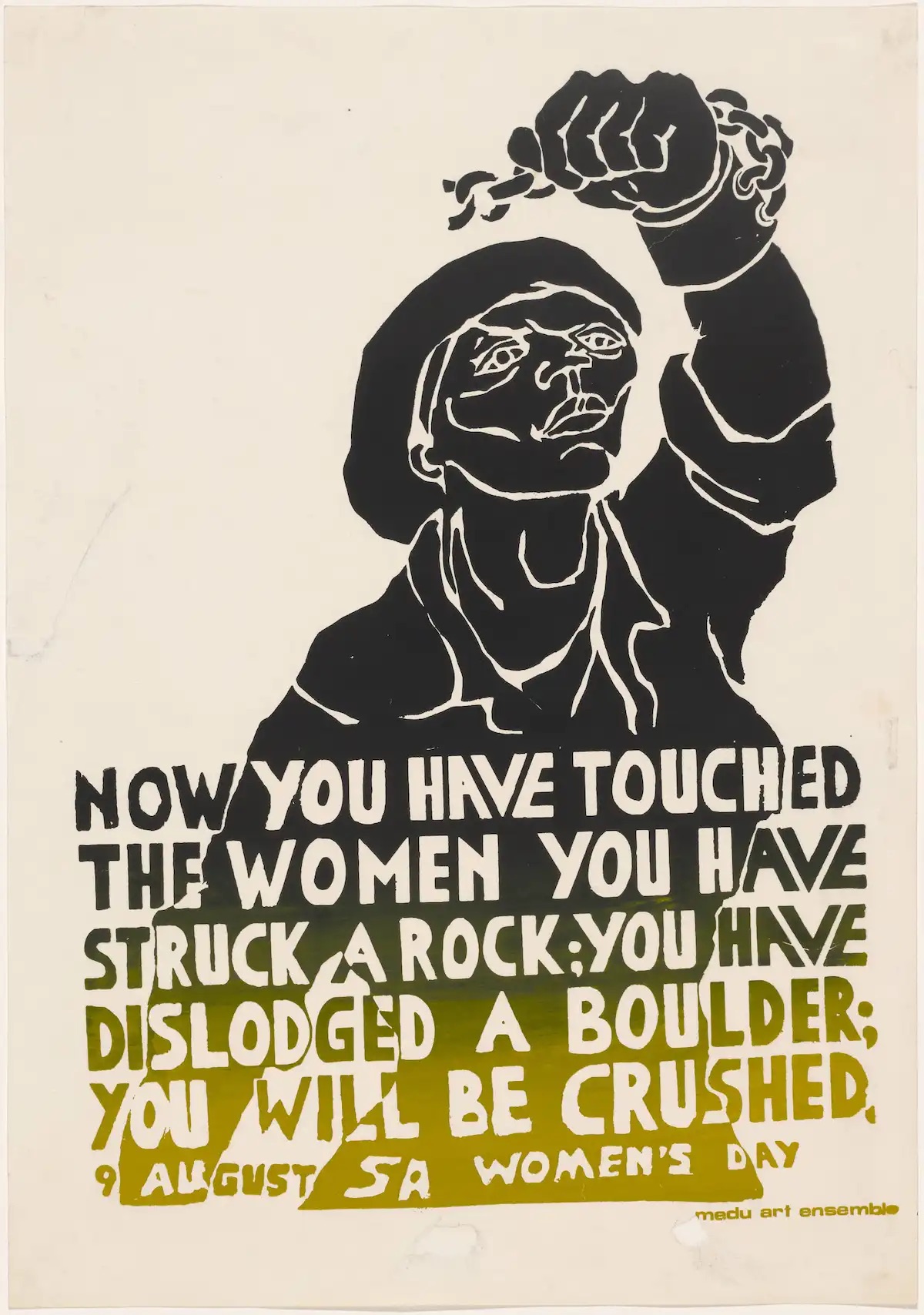

On 9 August 1956, now commemorated as Women’s Day in South Africa, Ngoyi and other woman leaders led an estimated 20,000 women to the Union Buildings in Pretoria, the seat of power of the white minority government. They were protesting extending the much-hated pass laws to women. These laws required black citizens to carry pass documents to better control their movement.

Beyond this, Ma-Ngoyi, as she was affectionately known, remains an often-mentioned but somewhat two-dimensional figure in history.

Perhaps because she was not the wife of a high-profile ANC leader and lived much of her life as a banned person, dying in penury, there is no Lilian Ngoyi Foundation and no substantive biography. Yet the pioneering role she played, and the sacrifices she made, extended well beyond the Women’s March.

Upbringing

Born Lilian Masediba Matabane in 1911, Ngoyi had a different life from other anti-apartheid struggle stalwarts. Not only was she an independent woman, but she was born into urban poverty. She did not hail from a royal or rural household like the Mandelas, Sisulus and other elite members of the ANC, whose role in the fight against apartheid is well documented.

Ngoyi was the granddaughter of a trailblazing Methodist minister, a historical figure in his own right. But his extraordinary contribution to the missionaries’ endeavours in southern Africa did not translate into any significant upward mobility for the family.

Her mother, though literate, worked as a washerwoman and domestic worker and her father was a miner and labourer, who died of mining-related lung disease. As the only girl in a family of four, she was the last in line when it came to education. Still, Ngoyi’s family rallied to keep her in Kilnerton, a leading black Methodist school, even though she was only able to complete her junior schooling. She moved to Johannesburg to take up a short-lived position as one of the country’s first black female trainee nurses at City Deep Mine Hospital.

Her youth typified the contemporary experience of many black women in urban South Africa. She fell pregnant at 19, married at 23, but was widowed at 26. She took on the care of her newborn cousin when her brother’s wife died, and was the primary carer for her elderly parents.

The family spent a miserable decade living in The Shelters, the site of the country’s first urban land invasion under the charismatic James Mpanza, who encouraged backyarders to occupy open land in Orlando, Soweto. Here, Ngoyi experienced the indignity of poverty first hand.

Defiance

Politics changed everything for her. In 1953, at the tail end of the Defiance Campaign, a mass non-violent resistance protest, Ngoyi risked a three-year prison sentence by walking into the whites-only section of a Johannesburg post office. Apartheid laws created and policed racially segregated spaces and to defy them took great bravery.

Ngoyi became an ANC member and rose rapidly through its ranks. She joined the newly formed Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw), forging a lifelong friendship with trade unionist and activist Helen Joseph. A broad-based coalition of women’s organisations, Fedsaw was the organiser of the 1956 march, with Ngoyi and Joseph leading the way.

Ngoyi had the skill to inspire mass mobilisation and bring people together, especially women. By all accounts, she was an exceptional orator. In a 1956 profile in the leading black magazine of the day, Drum, author and activist Ezekiel Mphahlele wrote:

She can toss an audience on her little finger, get men grunting with shame and a feeling of smallness.

Anti-apartheid activist and wife of Nelson Mandela, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela recalled:

She spoke the language of the worker, and she was herself an ordinary factory worker. When she said what she stood for, she evoked emotions no other person could evoke.

In 1955 Ngoyi was sponsored for an overseas trip by the Women’s International Democratic Federation, regarded as a Soviet Front organisation. She attended conferences and propaganda tours in Europe, China and the USSR.

She returned home to the government’s plans to extend the pass system to women. The experience abroad, of being treated like a human being for the first time, had invigorated her. Ngoyi set about canvassing support for the famous march. The largest gathering of women in the country’s history, it was the kind of mass mobilisation the ANC men had only dreamed of.

In 1956 Ngoyi was among 156 dissidents arrested in a swoop by security police. Charged with treason, they became known as the Treason Trialists. She was finally acquitted in 1960, but had lost her job as a factory machinist. She was soon arrested again and detained for five months, 19 days of which she spent in solitary confinement. In a 1963 arrest, she spent 71 days in solitary, an experience which affected her ability to focus.

Isolation

Thereafter, Ngoyi drops out of history. She was subjected to three five-year banning orders, living in a state of permanent lockdown. For most of the remainder of her life she was forbidden from interacting with other banned persons. She was unable to meet with more than three people at a time and could not attend a lecture, go to the cinema or accept invitations to weddings, funerals or parties of any sort.

The banning orders ended her political career and gradually eroded her ability to earn a living as a seamstress, unable to travel into town to purchase fabrics. Security police frequently raided her home, chasing away potential customers. Ngoyi was forced to rely on sporadic donations. In a letter of gratitude to a sponsor, she expressed the humiliation of her position:

We feel small to say thanks all the time.

Not the wife of an elite ANC leader, she received no financial contributions from exiled men, nor was she supported by the International Defence and Aid Fund, which helped the families of political prisoners. She did not lose hope, however, and like Mandela, took solace in gardening, planting seeds sent to her by her overseas friends. Her small yard was full of blooms.

On 13 March 1980, two months before her third banning order was due to expire, Ngoyi passed away, aged 69. She never saw freedom in her lifetime, nor did she receive the recognition she deserved for her efforts to achieve it. At her funeral, activist and church leader Desmond Tutu said that when the true history of South Africa was written Ngoyi’s name would be in “letters of gold”.

This has manifested to some extent – a few clinics and roads bear her name. But the true nature of her accomplishments and challenges, and those of other banned and banished persons in South Africa, should never be forgotten.

Martha Evans is a Senior Lecturer in Media Studies, University of Cape Town

This article was first published in The Conversation.