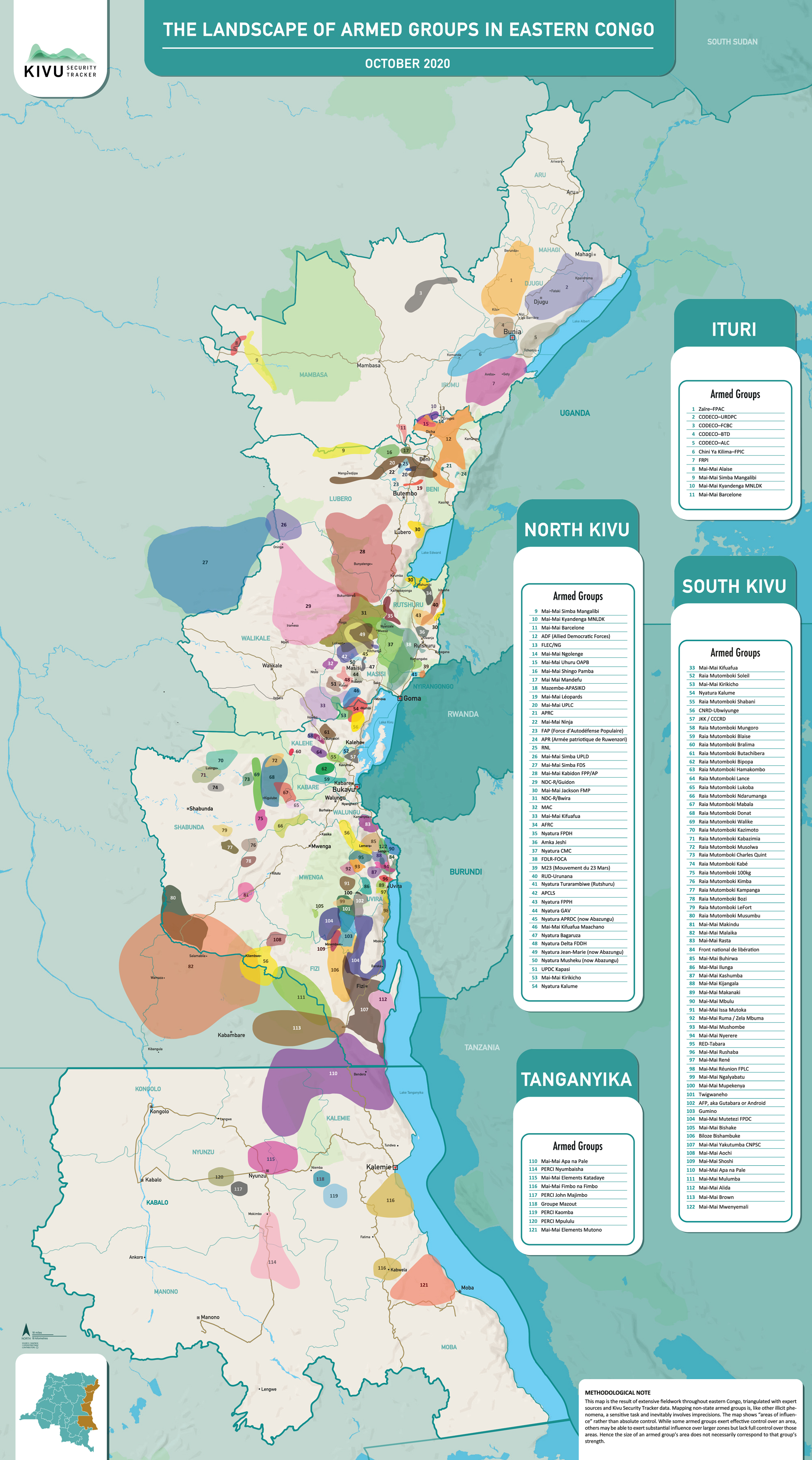

Since 1996 the people in Kivu have not been in peace despite the presence of the so-called UN Peace Keeping Force MONUSCO (United Nations Organization Mission for the Stabilization of the Congo) and a great number of humanitarian organisations. Thousands of people have been killed, houses and other assets have been burned, and people have fled from their homes to more secure areas where they are suffering from malnutrition.

The situation has worsened since 2014, particularly in North-Kivu where mass killings occur every day. But why is the international community keeping quiet? What is the purpose of these killings?

Divide and rule

The Democratic Republic of Congo is rarely if ever at the top of Western headlines, but heads of state and so-called experts have long made similar proposals to carve out new, smaller, more homogeneous nations in Congo’s resource-rich eastern provinces.

Attempts to break up the Congo began as soon as the country became independent in 1960. First there was the Katangese secession, from 1960 to 1963, led by Moïse Tshombe with the support of Belgium, the colonial power that Congo had just freed itself from, in name at least. Katanga is Congo’s most southeastern province, bordering Angola, Zambia and Tanzania, which makes it easier to slice off, like the rest of the resource-rich eastern border provinces. Katanga is also Congo’s most mineral-rich province, and the Belgians had made it clear, before independence, that they did not intend to cede control of its wealth to the Congolese. Another secession began in the southern part of Kasai Province, which borders Katanga. These secessions were defeated by UN forces and the Congolese army led by Lt. Gen. Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who was then chief of staff of the armed forces.

In October 1996, Rwandan President Pasteur Bizimungu called for a new Berlin Conference, referring to the 1884 gathering that regulated the partitioning of the African continent among 14 European states and the USA, to allow Rwanda to take possession of part of eastern Congo. Bizimungu was a Hutu figurehead concealing the minority Tutsi rule that General Paul Kagame had re-established at the end of the 1990-1994 invasion, war and genocide in Rwanda. At the same time, US official and corporatist Walter Kansteiner began advocating ethnic Balkanisation, including the creation of a homogeneous Tutsi state in eastern Congo. He’s been involved in mergers, acquisitions and privatisations all over Africa, and he owns a commodity trading firm in Chicago that specialises in tropical products. He’s a member of the Corporate Council on Africa, the Council on Foreign Relations and the African Development Foundation.

In 1998, during the Second Congo War involving nine African countries, the DRC and its vast resources were divided into three main parts, even though there was no formal secession. One part was controlled by Congolese President Laurent-Désiré Kabila and his allies, another by Rwandan President Paul Kagame and his allies, and the third by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and his allies. This de facto partition of the country ended in 2003 when the Sun City peace agreement was signed in South Africa. This was in fact an agreement between the Rwandan government in Kigali, the Ugandan government in Kampala, and the Rwandan government in Kinshasa, which was pretending to be Congolese. The agreement marked the next stage in a long period of veiled occupation that continues in Congo today. By January 2009, French President Nicolas Sarkozy declared publicly that Congo must share its space and wealth with Rwanda.

There are now several initiatives aimed at Balkanising Congo, but the country’s population has always opposed them. That explains, for example, the defeat of M23, an armed Tutsi militia, in November 2013.

A petition was recently launched by individuals who claimed to be from the Hutu community in Congo, calling for the partition of North Kivu, one of Congo’s most resource-rich and population-dense provinces. North Kivu borders Rwanda, and Rwandan forces have never left the province despite the 2003 agreement that formally ended the Second Congo War.

Instead, they pretended to be Congolese and renamed themselves the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP) and then the March 23 Movement (M23). North Kivu continues to be ravaged by their violence and looting of Congolese resources, including coltan, gold, diamonds and timber.

This partition of North Kivu would weaken the inter-ethnic cohesion of the province, weaken its different territories and cause massive population displacements. There are already more than 1.1 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in North Kivu Province, nearly a quarter of the 4.5 million IDPs in the country.

Partitioning the territories of North Kivu would facilitate their annexation to Rwanda, as envisioned by the Balkanisers back in 1996. The people behind this petition are in fact linked to Kagame and Kabila’s Tutsi allies, which have always worked together to Balkanise eastern Congo. This explains the massive presence of Rwandan Tutsi officers in the ranks of the Congolese army.

However, the Rwandan military presence is not sufficient to achieve Balkanisation. This also requires huge Rwandan populations on Congolese soil. Hence their massive arrival, particularly in North Kivu Province’s Beni Territory and Ituri Province. These Rwandans commit massacres against the indigenous populations, which explains the hostility of the Congolese to their arrival. The only way for them to have a homogeneous state is to slaughter 95 percent of the local population or drive them off their land. That explains in part the death of six million Congolese and the continuation of the massacres in eastern Congo.

But despite these unending massacres and millions of deaths, the Tutsi still remain a minority throughout the eastern Congo. They cannot create a homogeneous state in eastern Congo, but perhaps they can create a totalitarian state like Rwanda’s, where a tiny, super-militarised Tutsi minority reigns supreme over the country and crushes the majority Hutu population.

About the author

Maliyasasa Syalembereka Joas studied English at Bukavu Institut Supérieur Pédagogique. From 2002 until 2009 he was in charge of the Leaders Training Programme at the Syndicat de Défense des Intérêts Paysans. In collaboration with Agriterra, he facilitated farmers’ workshops in Rwanda, Kenya, Burundi, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Niger amongst others. From February 2016 to December 2018, Maliyasasa worked as an advisor to TRIAS in charge of Institutional Strengthening and Organisational Development. Currently, Maliyasasa works as a freelance consultant. He is fluent in French, English, Swahili, Lingala, Kinande and other languages.