Over the past few years the Rwandan Supreme Court seating as the Constitutional Court has established itself as a reliable force in considering challenges to unconstitutional laws. That’s why public interest petitions have arisen. In 2018, there was a petition about defamation and the Supreme Court largely ruled in favor of rights to expression. In response the president of Rwanda called for the repeal of the article that protected his office from defamation. The parliament proceeded to amend the law to meet his demands.

This was an outstanding achievement in both the field of journalism and free expression as enablers of a democratic society.

However, despite these achievements, the journey is incomplete. This constitutes the basis for which I have petitioned the Supreme Court of Rwanda on remaining laws. I believe, and several colleagues with me, the law still constitutes a challenge to free expression and journalism, in particular to investigative, undercover and open source internet, OSINT, journalism.

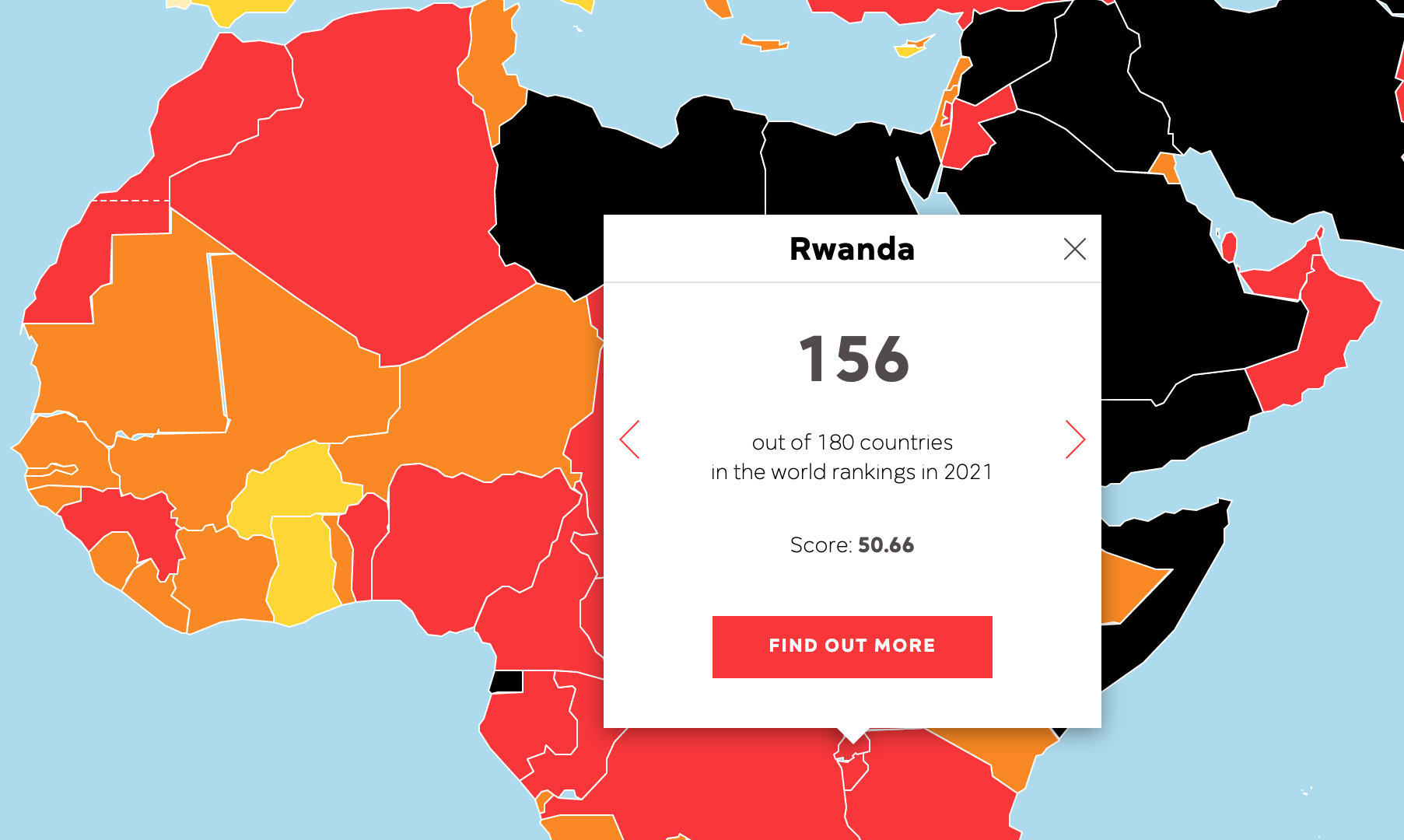

In Rwanda, over the last two decades, lots of reforms have been implemented in almost all sectors of society. In media, starting with the cabinet decision of May 2011, media reforms kicked off introducing the Access to Information Act, media self-regulation, a public broadcaster etc. However, in practice not much has changed since both have been implemented and the chilling effect of remnant laws and the ability of pro state actors to emphasise their dominance remains prominent. Investigative, undercover and OSINT journalism is possible and acknowledged, however its impact can be muted.

Therefore, on the basis of achievements so far and possible steps, I have identified articles in the various laws affecting media but are a hindrance to the practice of free expression. I decided to petition the supreme court to hear my arguments as to why they are against the spirit of the constitution that empathises free expression of a person and the media’s essential role in a democratic society.

Despite the supposed achievements on both policy and laws, covert censorship and self-censorship has curtailed the realisation of achievements that should have come through. I have identified certain areas, including the organisation of the economy, as well remnants of oppressive laws. While practice requires change of cultures, constitutionality requires change of laws. As explained above, a constitutional petition is a big step towards legislative change. The court can interpret the petitioned articles and order parliament to modify them. I identified articles that contradict the constitutional spirit: to encourage growth in a democratic free expression.

When you look at African countries, media conflicts happen less frequently. The expansion of democratic practices, greater domestic and international support for human rights and the emergence of a vigorous and independent civil society all have improved the media climate. However, in Rwanda civil society is very weak. It fears to antagonise the state. This is why civic organisations are hardly involved in public interest litigation. It necessitates our individual intervention.

Still, one of the biggest problems many African countries face is the prosecution of and violence against journalists. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) provides annual data on the impunity journalists face. Among the curtains behind which these perpetrators hide are laws.

The year 2020 has been proven to be one of the most dangerous years for specifically African journalists where some were killed on assignments and others in custodies. Others were arrested at work, others harassed. The main fuel of this are legal articles obstructing press freedom across the continent. Government propagandists, repressive judges, corrupt officials, criminals, commercial bullies, and cynical tabloid proprietors have always been the enemies of honest reporting; their power remains strong.

Again, I agree that the situation of press in Rwanda has improved up to a certain degree. There is progress in terms of arbitrary attack and detentions of journalists and closure of publications. This is also the case when it comes to the implementation of laws aimed at creating an open environment. But there are still some repressive laws that endanger the freedom of media in general and contribute to a climate of fear.

Honestly, one of the biggest challenges for Rwandan media is the lack of solidarity amongst its practitioners and financial support. This is actually one of the reasons why I decided to petition the Supreme Court on an individual basis.

In a recent interview with a local media platform, a journalist asked why I never petitioned through local media associations, like the Rwanda Journalist Association (RJA) or Rwanda Media Commission (RMC). My answer is very clear: they are less aligned to independent journalism and are led by people that work with the state media. They tow the line that has been put in place to repress independent journalism.

Some organisations, RMC as a media self-regulatory body in particular, have for the last two years failed to conduct elections of new board members even after pleas from journalists to do so. This shows that they don’t serve the interests of journalists but rather someone else. On top of which, they have on several occasions denounced arrested journalists.

One of the legal articles challenged is 194 of the Penal Code which punishes ‘publication of false news’. This is problematic for journalists since it is regularly used to suppress controversial views. Through their Supreme Courts, Commonwealth countries like Canada, Zimbabwe and Uganda have struck out the law ruling that it is incompatible with the right to freedom of expression. The Uganda court noted that freedom of expression doesn’t protect the truth, it is also abused for political purposes.

The chilling effect of the present Rwandan legislation is real. There are three journalists – Shadrack Niyosenga, Damascene Mutuyimana and Jean Baptiste Nshimiyimana of Iwacu TV – in prison awaiting trial for three years already. They face up to 10 years in prison for breaking the false-news-with-intent-to-tarnishing-Rwanda’s-image-abroad-rule. As if any journalist or any other person’s expression has any obligation to promote some country’s image!

Another regularly utilised law to limit press freedom is the requirement in the civil procedure for photojournalists to seek permission from the president 48 hours before they intend making photos in court. While it is understable for the need to keep order in court, in practice this law is applied arbitrarily and the 48 hour requirement is impractical since most journalists learn of court hearings a few hours in advance. I petitioned the Supreme Court to rule this obligation unconstitutional.

After a review of the Penal Code in 2018, most criminal defamation articles were scrapped by parliament and the Supreme Court. However, article 218 concerning ‘defamation of workers of international organisations’ stayed. This is contrary to the spirit under which all other forms of defamation where decriminalised. It is most likely an oversight. This petition offers an opportunity for this process to be completed.

Unlike the Penal Code passed in 2012, which provided for journalistic exceptions to an individual’s privacy in case of public interest, the law passed in 2018, eliminated this exception. We are asking court to consider reinstating this exception.

While the changes in law may not by themselves be sufficient to guarantee total freedom of expression, I believe my public interest litigation is a strong step towards eliminating remaining legal challenges faced by practicing journalists in Rwanda.

I am aware that even right now there are fellow journalists and other Rwandans who regard my petition as an attack on authorities that have been delighting in the very laws I am challenging. They do not consider my petition as constitutional.

I hope this will trigger a constructive debate between the media fraternity and the law makers as we trust that the Supreme Court will dispense fairness and justice in examining my petition.