‘Sandwich’ helps tech giants avoid tax in Africa via the Netherlands and Ireland.

Google's office at the airport residential area in Accra, Ghana, sits inside a plain white and blue two-storey building that could do with a coat of paint. Google, which made more than US$ 160 billion in global revenue in 2019, of which an estimated US$ eighteen billion in ‘Africa and the Middle East’, pays no tax in Ghana, nor does it do so in most of the countries on the African continent.

It is able to escape tax duties because of an old regulation that says that an individual or entity must have a ‘physical presence’ in the country in order to owe tax. And Google’s Accra office clearly defines itself as ‘not a physical presence.’ When asked, a front desk employee at the building says it is perfectly alright for Google not to display its logo on the door outside. ‘It is our right to choose if we do that or not’. A visitor to the building, who said she was there for a different company, said she had no idea Google was based inside.

Facebook is even less visible. Even though practically all 250 million smartphone owners in Africa use Facebook, it only has an office in South Africa, making that country the only one on the continent where it pays tax.

Brick and mortar

The physical presence rule in African tax laws is ‘remnant of a situation before the digital economy, where a company could only act in a country if it had a “brick and mortar” building’, says an official of the Nigerian Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS), who wants to remain anonymous. ‘Many countries did not foresee the digital economy and its ability to generate income without a physical presence. This is why tax laws didn’t cover them’.

Tax administrations globally have initiated changes to allow for the taxing of digital entities since at least 2017. African countries still lag behind, which is why the continent continues to provide lucrative gains for the tech giants. A 2018 PriceWaterhouseCoopers report noted that Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, has seen an average of a thirty percent year-on-year growth in internet advertising in the last five years, and that the same sector in that country is projected, in 2020, to amount to US$ 125 million in the entertainment and media industry alone.

‘Their revenue comes from me’.

William Ansah, Ghana-based CEO of leading West African advertising company Origin 8, pays a significant amount of his budget to online services. He says he is aware that tax on his payments to Facebook and Google escapes his country through what is commonly referred to as ‘transfer pricing’ and feels bad about it. ‘These companies should pay tax here, in Ghana, because their revenue comes from me’, he says, showing us a receipt from Google Ireland for his payments. During this investigation we were also shown an advert receipt from a Nigerian Facebook ad that listed ‘Ireland’ as the destination of the payment.

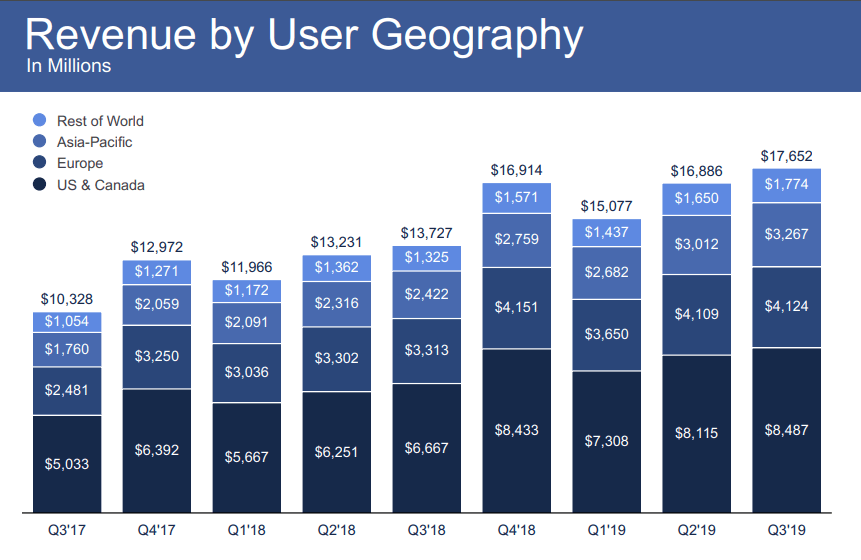

Like Google, Facebook does not provide country-by-country reports of its revenue from Africa or even from the African continent as a whole, but the tech giant reported general revenue of US$ sixty billion as a whole from ‘Rest of the world’, which is the world minus the USA, Canada, Europe and Asia.

Irish Double

The specific transfer pricing construction Google and other tech giants such as Facebook use to channel income away from tax obligations is called an ‘Irish Double’ or ‘Dutch Sandwich’, since both countries are used in the scheme. In the construction, the income is declared in Ireland, then routed to the Netherlands, then transferred to Bermuda, where Google Ireland is officially located. Bermuda is a country with no corporation tax. According to documents filed at the Dutch Chamber of Commerce in December 2018, Google moved US$ 22,7 billion through a Dutch shell company to Bermuda in 2017.

Google Ghana is an ‘Artificial Intelligence research facility’.

An ongoing court case in Ghana — albeit on a different issue — recently highlighted attempts by Google to justify its tax-avoiding practices in that country. The case against Google Ghana and Google Inc, now called Google LLC in the USA, was started by lawyer George Agyemang Sarpong, who held that both entities were responsible for defamatory material against him that had been posted on the Ghana platform. Responding to the charge, Google Ghana contended in court documents that it was not the ‘owner of the search engine www.google.com.gh’; that it did not ‘operate or control the search engine’ and that ‘its business (was) different from Google Inc’.

Google Ghana describes itself in company papers as an ‘Artificial Intelligence research facility’. It says that its business is to ‘provide sales and operational support for services provided by other legal entities’, a construction whereby these other legal entities — in this case Google Inc — are responsible for any material on the platform. Google Ghana emphasised during the court case that Ghana’s advertising money was also correctly paid to Google Ireland Ltd, because this company is formally a part of Google Inc.

Rowland Kissi, law lecturer at the University of Professional Studies in Accra describes Google’s defence in the Sarpong court case as a ‘clever attempt’ by the business to shirk all ‘future liability of the platform’. Kissi is cautiously optimistic about the outcome, though: while the case is ongoing, the court has already asserted that ‘the distinction regarding who is responsible for material appearing on www.google.com.gh, is not so clear as to absolve the first defendant (Google Ghana) from blame before trial’. According to leading tax lawyer and expert Abdallah Ali-Nakyea, if the ‘government can establish that Google Ghana is an agent of Google Inc, the state could compel it to pay all relevant taxes including income taxes and withholding taxes’.

Cash-strapped countries

Like most countries, especially in Africa, Nigeria and Ghana have become more cash-strapped than usual as a result of the COVID 19 pandemic. While lockdowns enforced by governments to stop the spread of the virus have caused sharp contractions of the economy worldwide, ‘much worse than during the 2008–09 financial crisis’, according to the International Monetary Fund, Africa has experienced unprecedented shrinking, with sectors such as aviation, tourism and hospitality hardest hit. (Ironically, in the same period, tech giants like Google and Facebook have emerged from the pandemic stronger, due to, among others, the new reality that people work from home.)

With much needed tax income still absent, many countries have become even more dependent on charitable handouts. Nigeria recently sent out a tweet to ask international tech personality and philanthropist, Elon Musk, for a donation of ventilators to help weather the COVID 19 pandemic: ‘Dear @elonmusk @Tesla, Federal Government of Nigeria needs support with 100-500 ventilators to assist with #Covid19 cases arising every day in Nigeria’, it said. After Nigerians on Twitter accused the government of historically not investing adequately in public health, pointing at neglect leading to a situation where a government ministry was now begging for help on social media, the tweet was deleted. A government spokesperson later commented that the tweet had been ‘unauthorised’.

Cost to public

The criticism that governments often mismanage their budgets and that much money is lost to corruption regularly features in public debates in many countries in Africa, including Nigeria. However, executive secretary Logan Wort of the African Tax Administration Forum ATAF has argued that this view should not be used to excuse tax avoidance. In a previous interview with ZAM Wort said that ‘African countries must develop their tax base. It is only in this way that we can become independent from handouts and resource exploitation. Then, if a government does not use the tax money in the way it should, it must be held accountable by the taxpayers. A tax paying people is a questioning people’.

‘A tax paying people is a questioning people’

Commenting on this investigation, Alex Ezenagu, Professor of Taxation and Commercial Law at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar, adds that in matters of tax avoidance by ‘popular multinationals such as Facebook and Google, it is important to understand the cost to the public. If (large) businesses don’t pay tax, the burden is shifted to either small businesses or low income earners because the revenue deficit would have to be met one way or another’. For example, a Nigerian revenue gap may cause the government to increase other taxes, Ezenagu says, such as value added tax, which increased from five to seven and a half percent in Nigeria in January. ‘When multinationals don’t pay tax, you are taxed more as a person’.

Nigeria has recently begun to tighten its tax laws, thereby following in the footsteps of Europe, that last year made it more difficult for the digital multinationals to use the ‘Irish Double’ to escape tax in their countries. South Africa, too, in 2019 tailored changes to its tax laws in order to close remaining legal loopholes used by the tech giants. These ‘could raise (tax income) up to US$ 290 million a year’ more from companies like Google and Facebook, a South African finance source said. With US$ 290 million, Ghana’s could fund its flagship free senior high school education; Nigeria could fully fund the annual budget (2016/2017 figures) of Oyo, a state in the south west of the country.

Waiting for the Finance Minister

Nigeria’s new Finance Act, signed into law in January 2020, has expanded provisions to shift the country’s focus from physical presence to ‘significant economic presence’. The new law leaves the question whether a prospective taxpayer has a ‘significant economic presence’ in Nigeria to the determination of the Finance Minister, whose action with regard to the tech giants is awaited.

In Ghana, digital taxation discussions are slowly gaining momentum among policy makers. The Deputy Commissioner of that country’s Large Taxpayer Office, Edward Gyamerah, said in a June 2019 presentation that current rules ‘must be revised to cover the digital economy and deal with companies that don’t have traditional brick-and-mortar office presences’. However, a top government official at Ghana’s Ministry of Finance who was not authorised to speak publicly stated that, ‘from the taxation policy point of view, the government has not paid a lot attention to digital taxation’.

He blamed the ‘complexity of developing robust infrastructure to assess e-commerce activity in the country’ as a major reason for the government’s inaction on this, but hoped that a broad digital tax policy would still be announced in 2020.” Until the authorities get around to this, he said he believed that, ‘Google and Facebook will (continue to) pay close to nothing in Ghana’.

Comment

Google Nigeria did not respond to several requests for interviews; Google Ghana did not respond to a request for comment on this investigation. Neither entities responded to a list of questions, which included queries as to what of their activities in the two countries might be liable for tax, and whether they could publish country by country revenues generated in Africa. When reached by phone, Google Nigeria’s Head of Communications, Taiwo Kola Ogunlade, said that he couldn't speak on the company’s taxation status. Facebook spokesperson Kezia Anim-Addo said in an email: ‘Facebook pays all taxes required by law in the countries in which we operate (where we have offices), and we will continue to comply with our obligations’.

Note: The figure of eighteen billion US$ as revenue for Google in ‘Africa and the Middle East’ over 2019 was arrived at as follows. Google’s EMEA figures for 2019 indicate US$ 40 billion revenue for ‘Africa, Europe and the Middle East’ all together. According to this German publication, Google’s revenue in Europe was 22 billion in 2019. This leaves US$ eighteen billion for Africa and the Middle East.

Olivia Ndubuisi is a Nigerian broadcast journalist who loves investigations.