Three images. That’s all I’d seen of Santu Mofokeng’s work before now. So when I rushed to FOAM, the Amsterdam based photography museum, I felt quite unprepared. What I knew was that he was a South African and that he shot in black and white. That was about it. However, the fact that Mofokeng was given a solo exhibition at FOAM raised my expectations.

I joined a guided tour by curators Hilde Haest (FOAM) and Joshua Chuang (based in New York) who has lately worked closely together with Mofokeng. Entering the first exhibition room, it took me less than half a minute to feel blown away by Mofokeng's photos. His pictures are so alive. You feel the buzz and the movement. You hear the noise and the voices. Sometimes loud, sometimes like a whisper.

Take the example of a series called Train Church. All shot inside overcrowded commuter trains between Soweto and Johannesburg. You see people performing and undergoing spontaneous and intense religious rituals next to seemingly indifferent commuters, staring out of the window. These photographs are so dynamic, so close. Mofokeng doesn't only show, no, he puts you there.

He was a lousy photo journalists because he couldn’t keep deadlines.

Train Church was shot in 1986, a year after he established himself as a freelance photographer associated with photo agency Afrapix. Until then, he had done some street photography while earning money by assisting professional photographers in dark rooms of several news outlets. From 1985 till 1988, Mofokeng worked as a freelance photo journalist. But a lousy one, as he himself says, mostly because he couldn't keep to deadlines. He didn't drive and was therefore often late to file his pictures.

Already at Afrapix, Mofokeng grew dissatisfied with the dominant strand in news photography that predominantly highlighted the violent clashes between the Apartheid regime and the black population. Instead, Mofokeng turned his gaze more inwards, to places where most photographers didn't go: townships. Born and raised in Soweto he started documenting his immediate surroundings, the people he lived with, daily township life.

In this period he developed his talent to tell real stories, feeling a strong urge to go beyond the quest for that single image containing it all that is so characteristic of news photography. In 1988, Mofokeng got a job as a documentary photographer/researcher at Wits University (Johannesburg). No more daily deadlines and more time and space to work on longer projects, to produce series.

If the exhibition at FOAM makes one thing clear, it is Mofokeng's capacity as a storyteller. Many of his series are displayed or screened in such a way that you immediately recognize the storyline.

Some of the approaches Mofokeng uses in his photography may come straight out of a text book on storytelling. Take his eye for detail. That little part of the image that says much about something bigger, the particular that resonates with the universal. It allows for layered photographs, giving his work deeper meaning.

The image is always sweet and sour.

There is a picture in the exhibition in which you see the expression of fear on the face a domestic worker looking at her patron in a Soweto kitchen. It reveals her position in the household and for that matter the position of so many domestic workers. The fear in her eyes is something we can all connect with. Mofokeng is strong at capturing faces and body postures. In his series on the shebeens (illegal bars) he depicts not only happy faces. The image is always sweet and sour, as if he wants to say that under the roof of Apartheid, life was always difficult, but this did not stop some people celebrating good times.

His series on Billboards in the townships shows in different settings the stark contradiction between the idealized worlds of the advertisements and the lived reality beneath. There is one picture of a desolate crossing just outside a township. You see a large billboard high up in the air in the form of a huge box of Omo washing powder. This symbol represents market capitalism, the system Mofokeng finds equally capable of othering, as much as the old system it replaced: Apartheid. Hence the township where the billboard is situated. There is always a political layer in Mofokeng's work: unequal power relations are illustrated by bodily positions, facial expressions, interpersonal movement and artifacts.

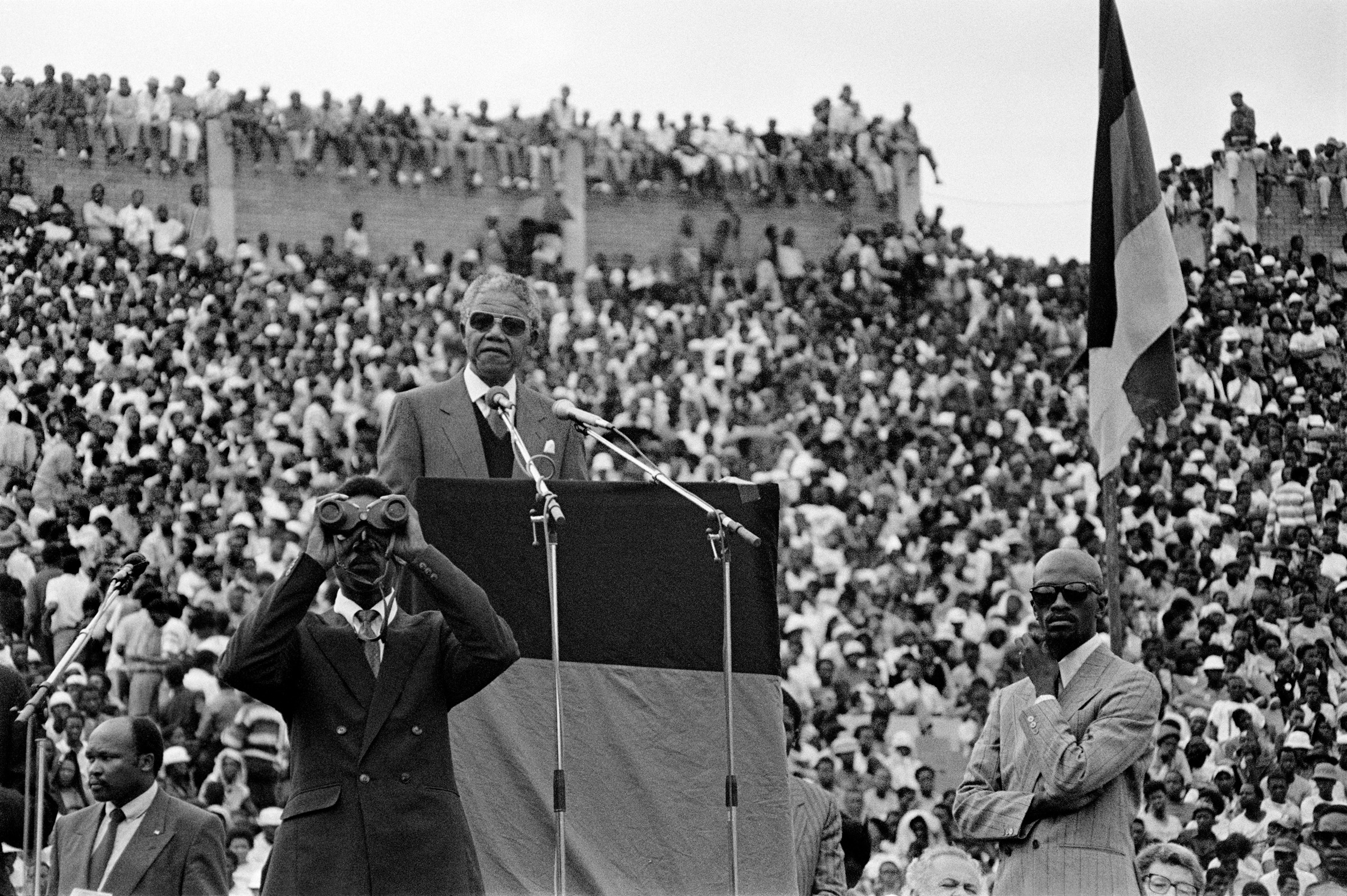

Some of his series also reveals a typical way of working used in storytelling: working your way from the outside in. An example of this is the series he shot at a political rally just before the first democratic elections. You first see the buzz outside of the stadium. There are many people around, maybe too many. They are sitting and standing on the outside walls. The following images come while he is working his way through the crowd in the stadium, portraying people getting excited about what is happing somewhere at the centre of the arena. He builds up tension. For the last picture, Mofokeng has entered the very middle of the stadium to shoot a picture straight in front of the main speaker of that day: Nelson Mandela.

One could say that Mofokeng points his lens to the left when everyone else is looking to the right, that he stays behind to see who or what is left when everybody else has joined the parade. That's a tried and tested strategy to find original stories. You see this on many levels in Mofokeng’s work. He focuses on daily life in the township instead of the violent clashes that reach the headlines. At the day of the first democratic elections in South Africa he doesn't stay in Johannesburg – where everyone gathers – but covers that day in Bloemhof, an isolated rural town he knew and of which he said that things weren't changing that fast. It was still feudal.

The emphasis of the exhibition at FOAM is on Mofokeng’s work in the 1980s and the early '90s. After 1994, the human figure gradually disappears from his images. Social life is replaced by landscapes. This also necessarily changes his approach to storytelling. It becomes less narrative, more abstract.

Curator Joshua Chang should be applauded for the time and effort spent on working through the more than 30 000 frames Mofokeng shot over more than 30 years. Through his edit Chang managed to bring the storyteller Mofokeng to the fore, disclosing many unpublished frames. The first few stories are on display at FOAM and all 18 stories will be published as Stories by Steidl Publishers.

Somewhere in an interview Mofokeng says “a photograph is an infidel”. The meaning given to a picture depends on whose looking. Well, at least in his pre-1994 work and from my perspective, I see stories well told, deeply political and often shot straight from the heart. Or should I say: straight to the heart?

Santu Mofokeng Stories is on at FOAM until April 28. On Thursday 4 April FOAM will organise an evening of conversations and music inspired by Mofokeng's life and work. More information here.