T-shirts, donated by international do-gooders, feature in Roxo’s exhibitions The Hands that Feed You and Objects in Transit.

How do the t-shirts illustrate the relationship between Africa and countries with 'interests' in Africa that your work interrogates?

The t-shirts are sourced and selected from ‘informal’ markets in Maputo. Locally, the t-shirts are called 'Calamidades' — directly translated from Portuguese as ‘Calamities’ given that they have come to represent the humanitarian aid agencies efforts to help Mozambique in times of natural disasters, like the floods, that impact local communities. All kinds of second-hand items are sent in bales and these fill the sidewalks and markets in Maputo. Initially intended as support, or ‘foreign aid’ these objects become an alternative source of income for locals as they are sold on through the street markets. Ultimately, this act of giving has a negative effect on local creativity and production, making us more dependent on the outside world and consequently more vulnerable. My intention is to transport these items back to the ‘North’, from where they came, to give charity back to the source, a gesture that can be read as a kind of ‘thanks but no thanks’. In the context of my work, the t-shirts represent this mass inflow of ‘aid’. I use the messages they carry and repurpose these for the gallery space to change their status. It is important for me to show that despite the good intentions, the system of foreign aid has a direct and often unforeseen impact on the local economy, eroding production and traditions of craftsmanship.

What is the importance of craft and handwork to your practice? Can you explain how you collaborate with artisans in Maputo?

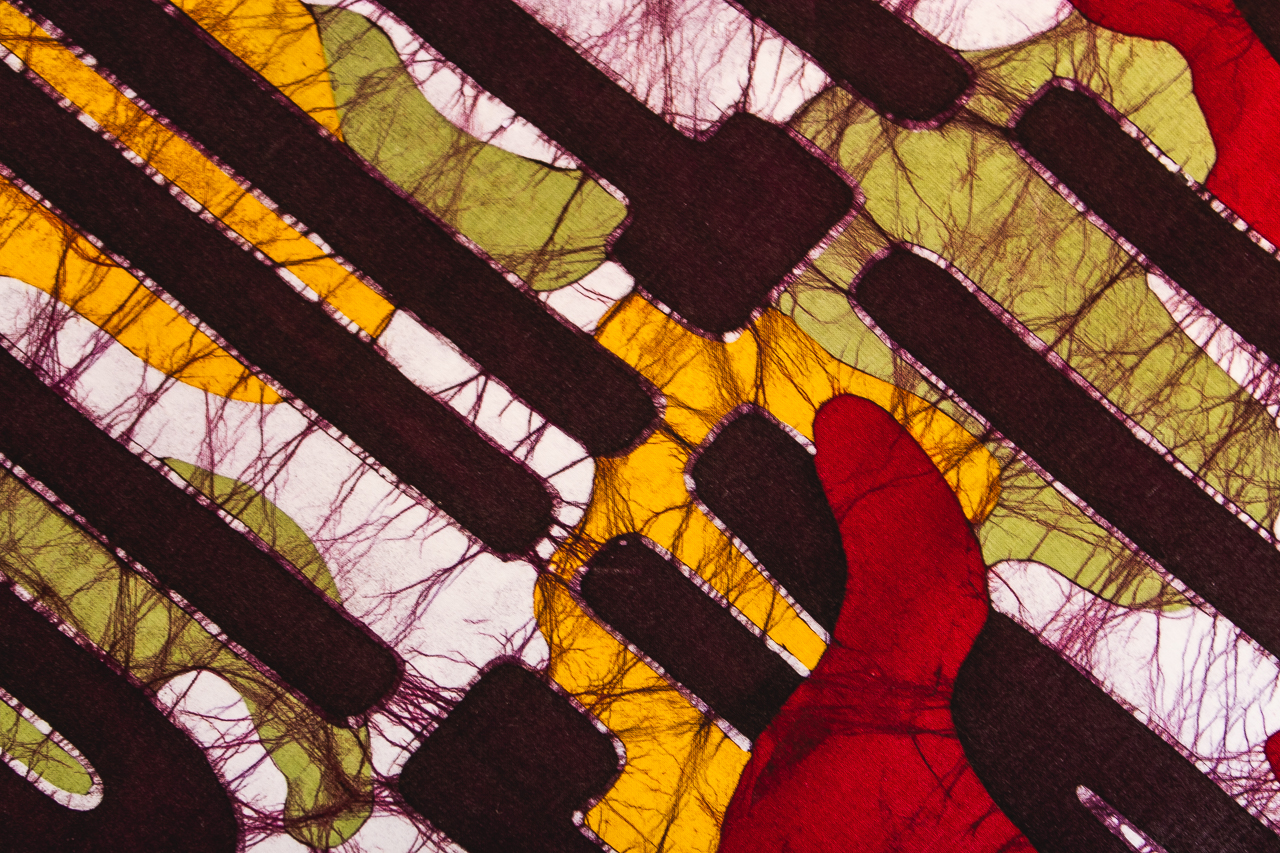

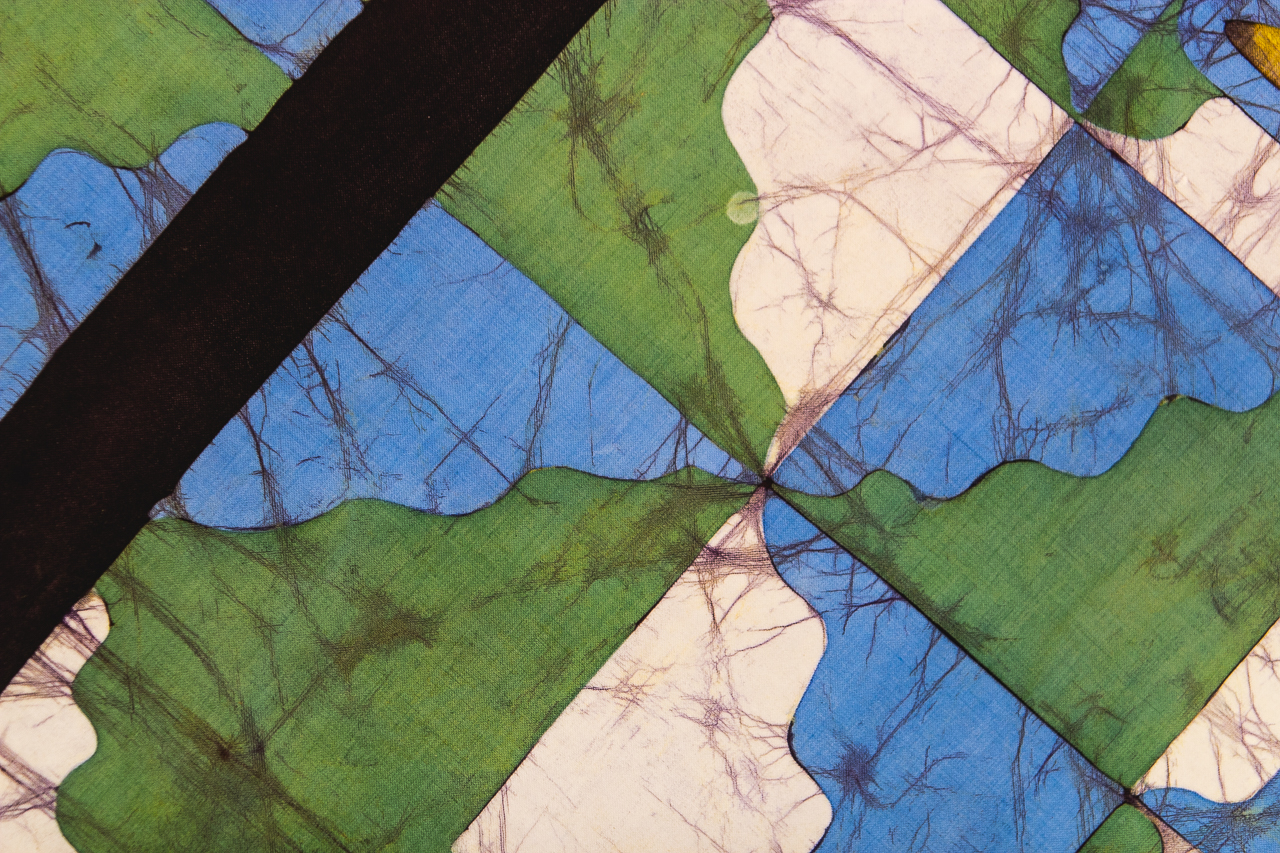

For as long as I can remember, growing up in Mozambique, I have had an interest in craft and handwork. More recently I have been exploring its place and potential in art and design practices. In my view, craft occupies a unique space between art and design. On the one hand, every piece is unique, expressing the hand of the artisan. On the other hand, and we see this a lot with the production of curios in Mozambique, handmade products become ‘replicas’, following the laws of supply and demand. So, these objects are neither completely unique, nor exactly the same. The characteristic ‘naivety’ of craft, which I read as a kind of beauty, always fascinated me. Walking around the city, meeting with artisans that work with wood, straw, wire, fabric and other materials, I began to explore the boundaries and bridges between handcraft objects and the digital, or my own practice and training as a graphic designer. In the process I have uncovered a hybrid world that expresses both the mathematical capacities of the digital and the unexpected, non-replicative outcomes specific to handcraft and craftsmanship. The batik prints that are central to both exhibitions are the result of this process, collaborating with artisans in Maputo who make batik for the local and tourist market.

I see a concerted effort in your work to distort or dissolve the grid that underlies a European tradition of design practice. Can you comment on how this tension plays itself out in your work?

I give more space to error and distortion

Indeed, in my work I face a constant dialogue between formality and informality, finding expression in the intersection between both tendencies and processes. My interest and origin in design come mainly from a European context as a high-school student in Maputo. Coming to Europe to study design, namely at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam, I felt strong urge to come back home, reflecting on local visual identity and how informal approaches, based on basic communication needs with no formulated processes, defines a unique, organic approach to creativity that challenge European traditions. To assimilate this approach into my work I have tested the rationality of the grid, giving more and more space to error and distortion, finding room for beauty in the unexpected. The grid will always play an important, underlying function in my work but now I rely on a more informal approach to flood the grid in unpredictable ways.

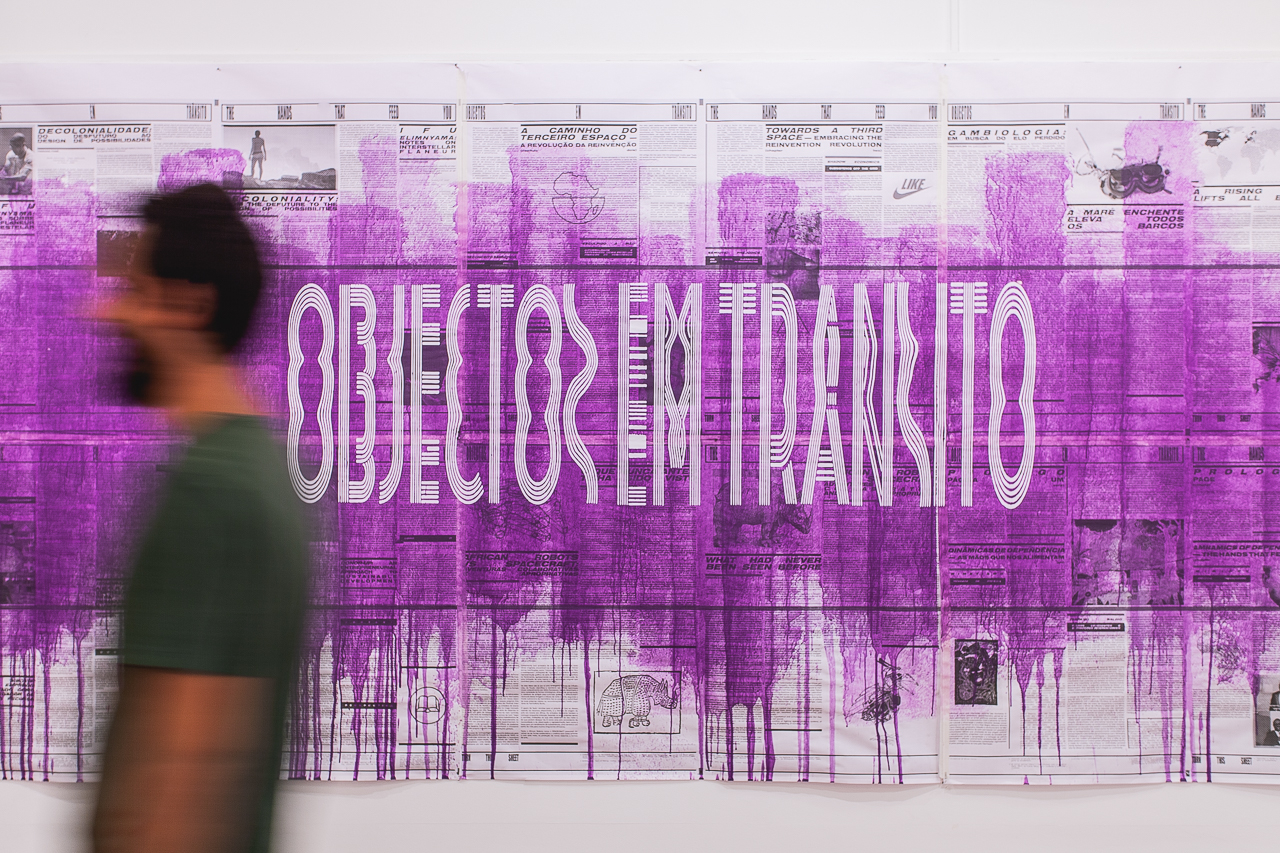

The Hands that Feed You focused on the t-shirts and the batiks. For Objects in Transit you have produced a series of screen prints. Can you explain how these fit into the objectives of the exhibition?

When exhibiting the work context is an important variable. Having an exhibition in Amsterdam was very different to having an exhibition in Maputo. Showing this work in my hometown brought back memories of my upbringing. One of the first and most important inspirations which made me want to be a designer and visual artist was the massive spread of propaganda material, clearly influenced by Russian constructivism, in post-independence Mozambique. This graphic language was spread in ideological publications and thematic posters (overseen, produced and published by the Ministry of Information and its National Department for Publicity and Propaganda) and these constituted a central means of identification for local audiences and myself. The screen prints in Objects in Transit are a direct play on this visual language.

For both exhibitions you have produced a newspaper/zine. How does this act of publishing function in the exhibition? Who has contributed to the newspaper and how is it distributed?

The journal/zine is the theoretical and narrative backbone of the project. It started in 2017 for The Hands that Feed You as a one-sheet ‘essay poster’. I chose this format to present my own writing on the topic. Part of the initial idea was to invite artists and thinkers to expand on the subject, and since then I had been sharing the work and looking for writers to participate. Fast-forward one year later to Objects in Transit and I was given the opportunity to produce a second edition of the journal. After inviting and painstakingly managing all the content production, I have been fortunate enough to have secured a great list of contributions for this issue: Fred Paulino (Brazil), Patrícia Anahory (CapeVerde/Portugal), Sul Sol Sal (Netherlands/Brazil/South Africa), Rafael Kouto (Togo, Suisse), Ralph Borland (South Africa), Russel Hlongwane (South Africa), Ruth Castel-Branco (Mozambique), Tassiana Tomé (Mozambique), Tavares Cebola (Mozambique) and Tiago Borges Coelho (Mozambique). All of the contributions offer a unique perspective, while connecting to the same central topic of global dependency and reflecting on the means and expressions of emancipation and self-reliance on the African continent. My intention is to make this a standalone publication, both online and through a periodically printed counterpart. For now, the latest issue has been sent to South Africa, the Netherlands, Portugal and London with the intention of spreading the work globally and hopefully finding new contributors for future issues.

Where is the work currently being shown and what are the future plans for the exhibition?

During the second half of 2018, in addition to Objects in Transit at the Portuguese Cultural Centre in Maputo, parts of The Hands That Feed You were shown in the 9th Printmaking Biennial Douro in Portugal. I was also invited to show the work at A School of Schools, a show curated by the collective Sul Sol Sal, as part of the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial in Turkey. From there, the batiks and zines will travel to Switzerland and Belgium as part of the same show next year. Added to this, along with Russel Hlongwane, the exhibition just won the Goethe Project Space fund and will be exhibited in Durban in 2019, possibly giving space for it to travel to Johannesburg as part of a series of programmed talks and exhibitions. As stated previously in this interview, as the shared and collectively generated content becomes the backbone of this project, I hope to see the work becoming a vehicle for a shared dialogue. The thinking is to initiate a curatorial process that invites artists and thinkers to share their views through a critical and speculative process. For this, the role of my creative counterpart Russel Hlongwane has become paramount to the work.

Final question. What role does the production of visual art and design from Africa have to play in a European context?

Africa is a bubbling pot of creativity. Since forever, strong local and regional identities have thrived on storytelling and the spread of knowledge through oral tradition. Nowadays, I believe, given the wave of uncertainty that characterizes contemporary life, a critical outlook is essential. A lot of the work coming from Africa represents this critical space – a hybrid, non-binary means for people to interact and overcome post colonialism and neo-colonialism. Increasingly, we are witnessing a debunking of established, calcified western models of knowledge and a reclaiming of vernacular, indigenous knowledge. Broadly speaking, through interaction and collaboration, I see creative communities in Africa setting the stage and forcing a shift from a vertical, hierarchical interaction into a more communal space.

João Roxo is a visual artist and designer living in Maputo, Mozambique. João is co-founder and head of design at Anima Creative Studio, the first local collective focusing on communication for art, culture and social development. In 2017 he graduated with an MA in Design from the Sandberg Institute, Amsterdam.

Oliver Barstow is online editor at ZAM