Once upon a time, I met a girl in a Lagos nightclub. She was a dancer. Her body was slim but spritely; her steps were lithe and nimble. Her laughter was like Lagos traffic at 4PM on a Monday, and when she wasn’t weaving gestures through the air, between the spindly fingers of her right hand dangled a thin Benson & Hedges, while the other was loosely draped over the armrest of the sofa.

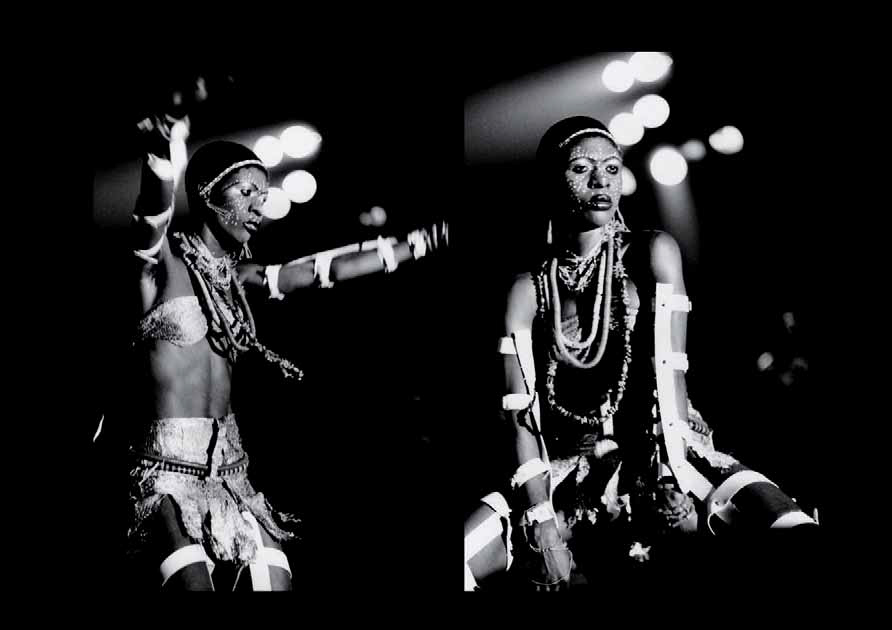

Later that night, in more intimate settings, I got to know she was a resident at The Shrine, one of Fela’s Kalakuta queens. Indeed, her athletic splits and acrobatic twerks were supple and well-choreographed, still I wondered if she was an inner circle queen-queen, or just a groupie from the Shrine, like some sort of Billie-Jean-Is-Not-My-Lover. Anyway, she was good company, and very many years later, I still remember her, at least for her raucous laughter.

At the time, I lived with my mom. It was my habit to walk around our house wearing nothing but boxer shorts, which hugged me tight in all the right places. Of course, the weather in Ibadan was hot, and in those good old days, I was not self-conscious in the least. Whenever I pranced around like so, Mother Dearest would shriek: “Báwo ni wàá se máa wo pátá kiri? Àbí ìwo náà fé di Felá ni?” “Why are you wearing underwear around my house? Or you want to be another Fela?” I did try to protest that these were not underpants, but boxers. Mum would have none of it. She promptly admonished me to go put some clothes on. I went in, and came back with knee-length knickerbockers. Then Mum would say “Ehen! Ìrínisí ni ìsoni l’ójo...” “Don’t forget you’re a doctor… ”

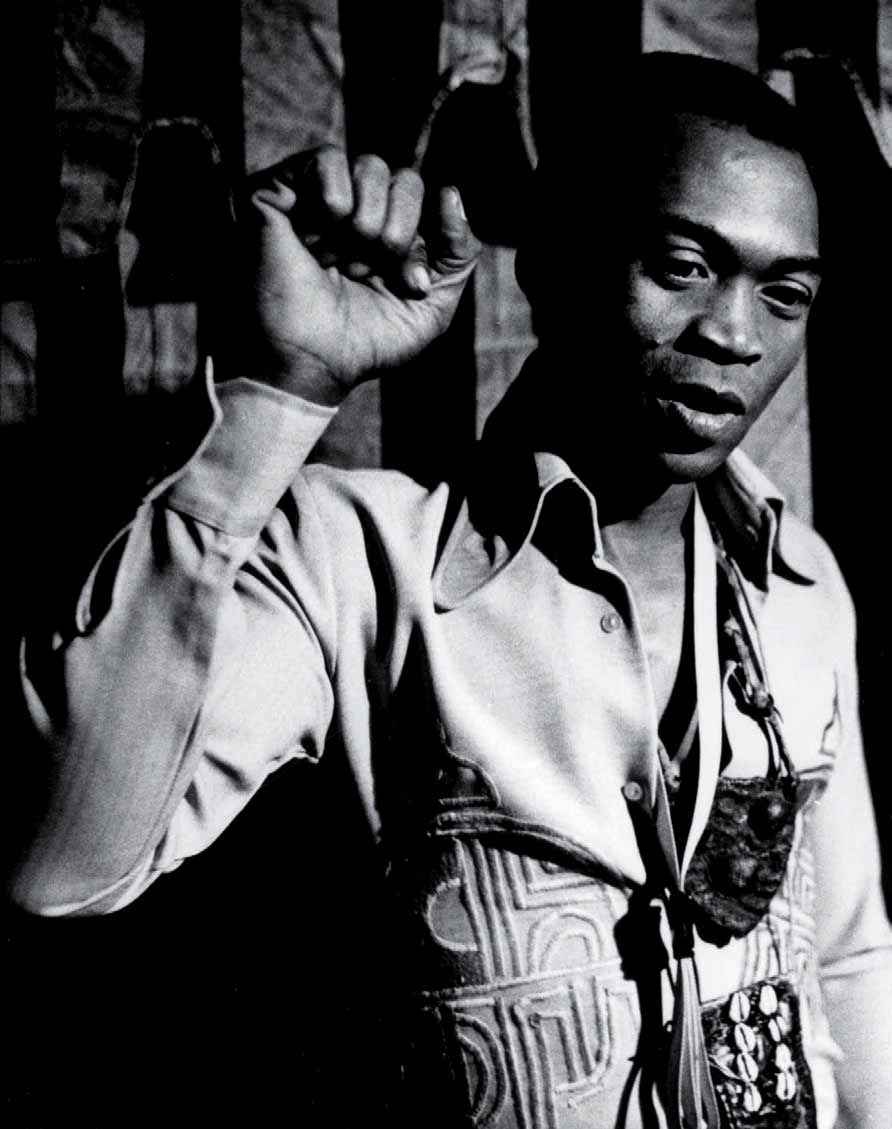

Truth is, I might have been both doctor and Fela: just like Fela started out, born to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a firebrand feminist activist, and Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, a school principal and reverend in Abeokuta; and growing up in Ègbá high society. Unlike me, Fela sacrificed medical school to acquire classical training at London’s Trinity School of Music.

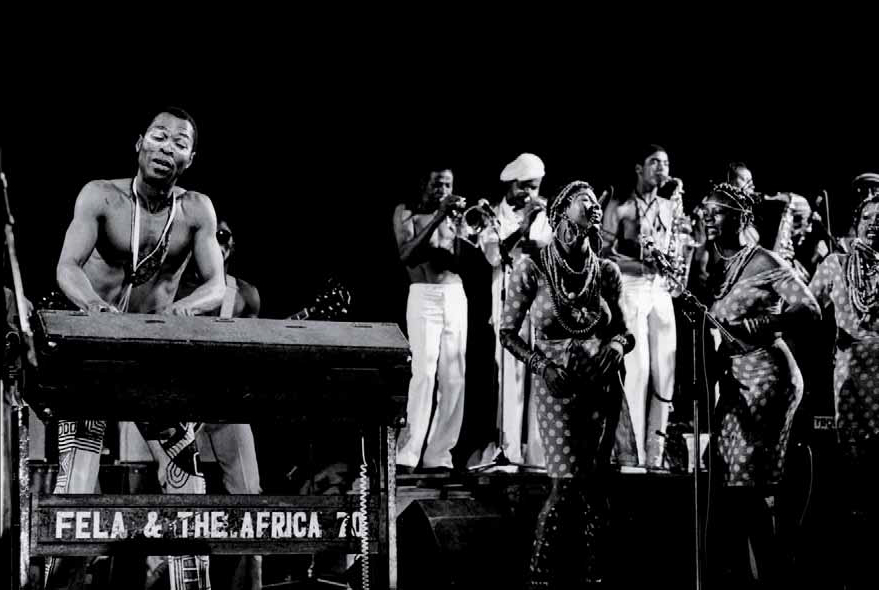

After that, his musical evolution came in stages, but eventually, Fela had developed a complex fusion of highly-structured classical music, American-style jazz, psychedelic rock, hard funk, Ghanaian-Nigerian highlife, and traditional Yoruba call and response. His live compositions were powered by shèkèrè, hard hitting drums, and a layered orchestra. This was Afrobeat, and its pioneer, and King was Fela.

But, the 60’s were the days of post-war liberalism, second-wave feminism, and the hippie revolution. Among blacks in America, there was a conscious movement and a nostalgic search for African roots: and so, a late 60’s tour of the United States with his Koola Lobitos band converted Fela from musician to activist. A year later, Fela returned to Nigeria with raised Black Power fists, a band renamed Afrika 70, and converted his Mushin home into a cultural capital called Kalakuta Republic.

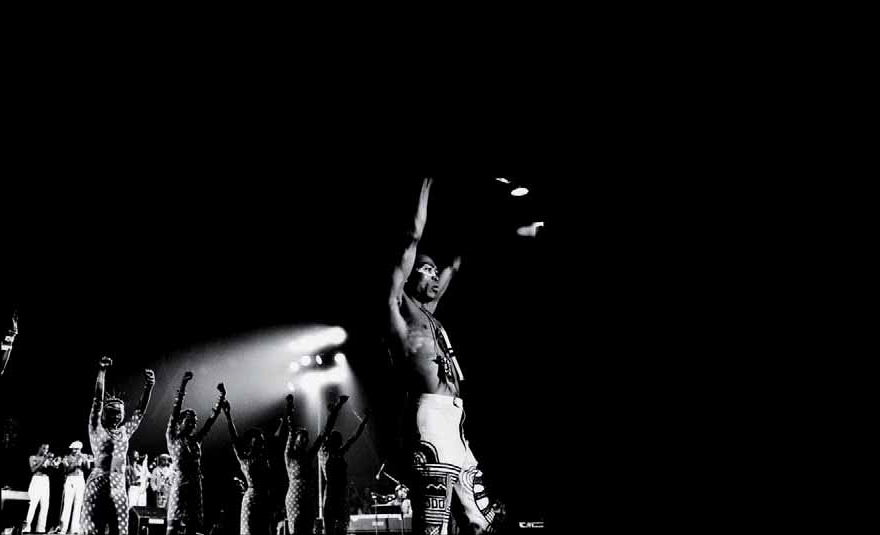

Fela’s new consciousness peaked during the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, or FESTAC, in Lagos. It was 1977, and Nigeria was reeling under the inebriation of a dreamy oil boom, so our military government threw a party for the whole world. Twenty-Nine days, 59 countries, 16,000 participants, and half a trillion dollars later, the strange one, Abami Eda, became a thorn in the flesh of the ruling military. Night after night, Fela’s advocacy drew performers away from the purpose-built National Arts Theatre, to the Shrine: including Stevie Wonder, who was televised live via satellite link from Lagos, for his appearance at the 19th Annual Grammy Awards.

That same day, Fela’s Kalakuta republic was invaded and razed to the ground, with a full battalion of soldiers numbering over one thousand men, beating and shooting its fleeing inhabitants. During the attack, the young women in the residence were brutally raped and Kuti’s 77 year-old mother was thrown from a second story window. She later died from her injuries. The pungent emotion of that night is vividly captured in Fela’s 1979 album Unknown Soldier, where he actually begins to cry as he sings: “dem kill my mama…”

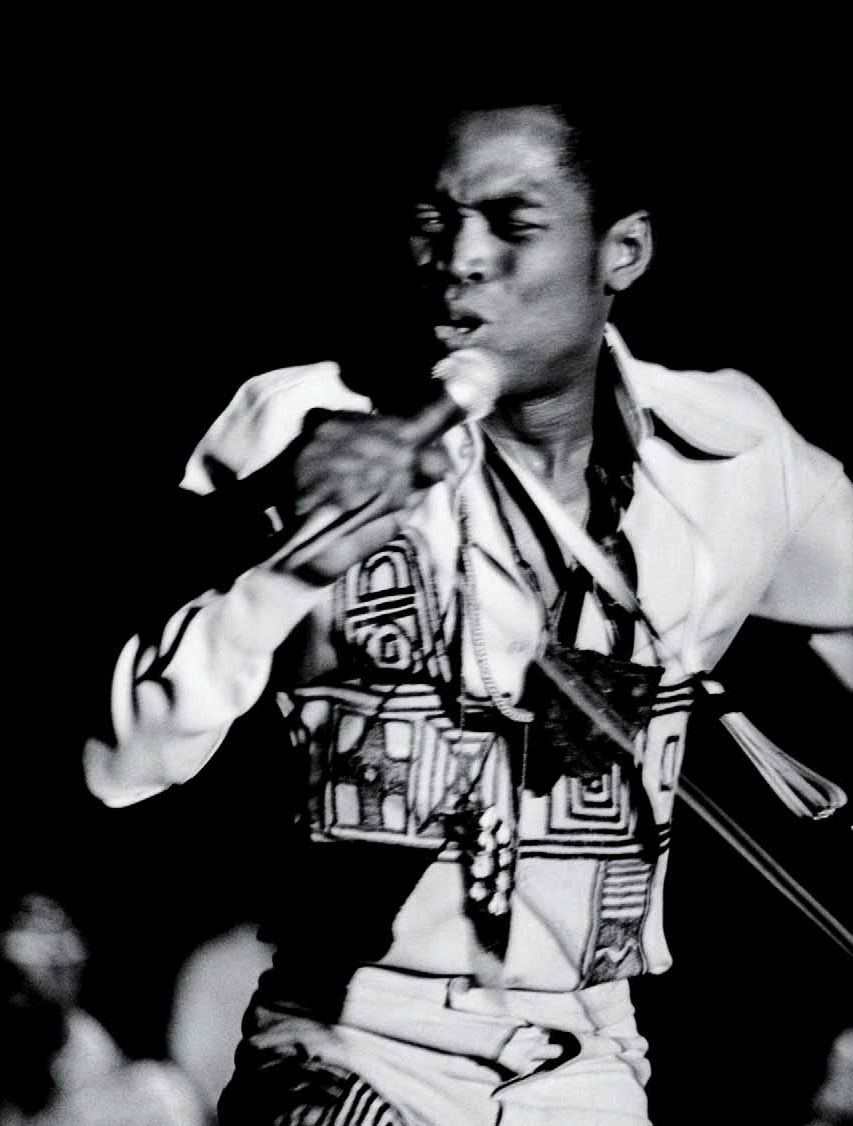

Today, the world celebrates the 80th anniversary of Fela’s birth. If I could travel back in time, I’d love to watch Fela perform live at The Shrine. I’d listen to him lay tracks; hear him say "2nd Base!"; Then see him do his signature shuffle, like a forward moonwalk. Then he might lift his golden sax, and his cheeks would swell like Dizzy Gillespie’s. He’d then strut confidently across the stage, in his elaborately embroidered tight fitting couture, and perform to an ecstatic crowd, while also challenging his audience with knowledge.

80 years on, Fela has created a global brand which has outlasted every person who criticized him while he was alive. On the other hand, the social and political issues which defined Fela’s anthems still remain, and while many people are entertained by Fela’s music and intrigued by his personality, many more need to listen to his message of empowerment.