Olivia Ndubuisi infiltrated one of the notorious ‘419 scams’ industry’s headquarters.

In this universe Nigerian young men use the internet to relieve unsuspecting ‘clients’ of their money in romance, gold, or business scams.

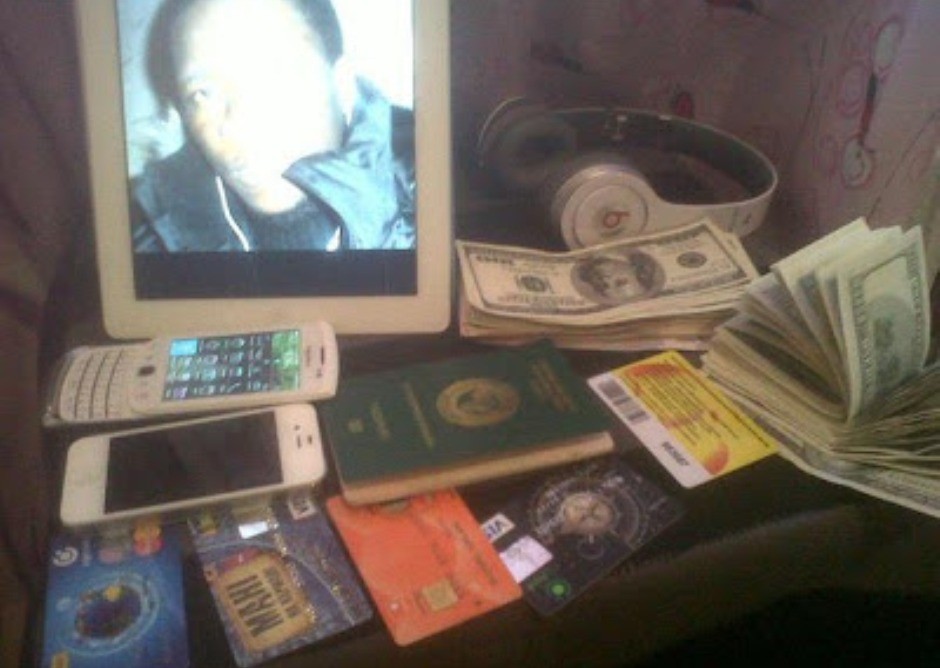

The Yahoo Boy rarely lives alone. He needs his comrades around him to pull off a successful scam: the document forger, the international call router, the bank account frontperson and the tech wizard are needed just as much as the smooth talker. Luckily for the Yahoo Boy this is not a problem, because the sector pulls in enough money to create room for everyone. An entire new building, tucked in the middle of New Haven, Enugu, Nigeria, houses scammers as well as the offices that produce the documents, stamps, phone connections and internet disguises they need.

In Nigerian reality no one depends on the state for anything

The noise that perpetually engulfs this building from electricity generators indicates, just like the business that is conducted here, a Nigerian reality where no one depends on the state for anything. There is no electricity just like there is no law and order, or opportunities to apply your skills in any useful sort of way. But there are plenty of opportunities in the Yahoo Boy universe. In this building in Enugu, the scammers are ‘businessmen,’ their victims are ‘clients’ and they only rely on themselves and one another.

Staying close

Okechukwu Nnadi would not say that to be a scammer is the best career choice for a young Nigerian, but, he adds, it will do in a situation where young graduates like himself have little to no other career opportunities. “‘It depends on what stage of despair you are in over life in general when you get in. (If you are desperate enough) you become eager to learn which brand of this business will pay you the most, and how soon. Then you learn what time of day is best to throw a bait and on what platform, how much time must pass before you check back in on a client. You learn that the business documents you need can be produced here in New Haven. That’s why we stay close.”

Once money is transferred by a victim, Nnadi and his colleagues do not stop until that victim has no more money and no one else to borrow from. As soon as one variety stops yielding, another is invented. The police don’t bother much; if a few Yahoo Boys are arrested in one region, they move to another.

A paper pushing job doesn’t pay for a Lexus

Nnadi holds a University degree from Nnamdi Azikiwe University. Even with Nigeria’s un- and under employment rate at 21%, leaving over a third of the population without enough to live on, surely he, Nnadi, could get some legitimate work with that? “What legitimate work?” is the answer. “How long do you have to work in the state civil service to be able to afford a car like mine?” An entry level graduate at the Enugu civil service earns 38,000 naira (about US$ 105) monthly. That cannot pay for Nnadi’s ‘Lexus Yahoo Boy,’ the Lexus Rx330 that has become a signature possession for the successful young men in the trade.

Okechukwu Nnadi was never too eager to go for a lowly paper pushing job anyway. He tells me that he got expelled from another, private university once, after he had sought excitement and material gain by joining a cultist association: a mix of a local gang, a militia, and a fetish-type religion of their own. Nigeria’s dysfunctional state structures simply don’t attract those who are, like him, cleverly ambitious. As we chat, it becomes increasingly clear that he is very proud of his scamming skills.

Appearing legit

He explains to me how a ‘serious Yahoo Boy’ can appear legit. If you’re selling romance, he says, ensure you are far away and there is no chance of you and your -middle-aged, lonely, female- client actually ever meeting. Nnadi was last paid by a woman living in Poland; he has friends currently receiving funds from ‘clients’ in Lithuania and Malaysia.

The romance scams are easy, Nnadi says. “As long as you do not visit her in her country and lose your home advantage, you are fine. I would, for example, never go to visit my present victim. After you have promised to go and failed even though she has sent you some money, she begins to doubt. It eventually fizzles out and you move on fast to others.”

Harder is, he says, the business scam, where someone orders actual material items from you: then you need to fake a ‘consignment’ and create shell companies. But they are good at that in the Enugu building. “One client was skeptical at first but by the time I had sent documents, she became convinced.” Okechukwu Nnadi and his colleagues will now ‘mould’ the documents, that is, add communications and a trail to show that the ‘consignment’ is being processed. “This woman will see receipts, proof that something is coming to her. She will be sent the name of the agent, a photo ID, the name of the airport and details of the consignment. Then her details will be sent to the ‘agent’. Her name, passport details, house address and phone number.”

There is no real agent and there never was a consignment. But the client will keep paying ‘for clearing.’

“Nigerians can also be duped, you know”

People in the West keep falling for this, he says, “because they believe in ‘online.’ Nigerians will doubt that such complicated business deals could be offered online but “since they (in the West, ON) have an online system that works, it is easy for them to believe the offers we make. But you (meaning me, the Nigerian, ON) can also be duped, you know,” he says then suddenly.

Me? I ask incredulously and he explains that it is possible to create fake profiles that convince even the very sceptical Nigerian. “You tell your victim, for example a middleclass woman, you are in Abuja,” he continues. “You do not use your own pic, you find a handsome man’s pic to use (usually one has a stash, having built many profiles on Facebook, ON.) You keep chatting with her. After a while you tell her that business will take you to the US but you will keep in touch from there. Before your ‘trip’ you send her a phone – a higher version of her present one. It convinces her that something real has happened. At this point, you introduce her to your ‘mum,’ who speaks to her on the phone from time to time. “This is done with the help of a Techno phone that has a voice changer. The voice of an elderly woman will tell her she can’t wait to meet you, God will bless your union with my son, etcetera. She will encourage the relationship and promise marriage.”

A phone call ‘from abroad’

The next phase is to call the victim ‘from abroad.’ “There is a guy who also lives here in New Haven, who codes the phone call so it appears to be originating from wherever you told her you were going.” Once convinced that you are really in the United States, she will be told that your mum has fallen ill and urgently needs N350, 000 (around US$ 1000, ON) for surgery. “You will send your ‘younger brother’ to her to explain everything and get the money. Of course, it is not your brother who goes, you are going yourself.” The face-to-face serves, besides to reassure the victim that the money will be repaid as soon as you are ‘back’ from America, also as a ‘physical recon’: “to know how much you will drill off of her eventually.”

But while fellow citizens, he says, are good “for the break in between when a real victim turns up online,” the best victims are still overseas. As Nnadi checks his watch and notices it is a few minutes to 8 pm, he says he needs to go because ‘Something will spoil’ if he isn’t online by then.

“You need to kill your conscience to be able to do this”

“You need to kill your conscience to be able to do this.” Tobe Ani is 28 years old and works -when he is not engaged in ‘yahoo work’- for tips in a restaurant lounge in Owerri, the capital of Imo state. It is his answer to a story I had shared with him: of a grandmother who took her own life after realising she had lost her savings to a scam. Ani adds that only with a tough conscience one can “move on fast after cashing out.”

In his case, he got involved when he realised he was not getting anywhere with his university degree in Biochemistry from Imo state University. Having started to moonlight as a comedian in a club, getting paid only a small token fee after his performances, he met successful Yahoo Boys who visited the club, splurging big time. Ani initially benefited already from his mere acquaintance with them: the more he would praise them during his performance, the more he would get a ‘large pay day’, too. After a while he joined them and he has been providing documents for scams ever since. “They come to me and detail what they want and I design and produce it. Whatever signature or stamp is needed.”

A third young man I speak to -let’s call him Arinze Amandi- has helped to provide international linkages for scams, working with “people whose sole job it is to provide foreign bank account numbers”. Amandi explains that “many travel abroad for this purpose” and that “they open an account in any particular country and wait for when a Yahoo Boy needs it”. When the account is used and money is sent by a victim, the money is then forwarded to the Yahoo Boy back home based on some agreed percentage through a domiciliary account, Western Union or MoneyGram. He adds that the received moneys can also be used to buy goods like cars, which are then shipped back home.

Amandi distanced himself from the practice when he started to feel sorry for the victims. “I worked with someone who told a victim he was gay.” (To be gay in Nigeria is a criminal offence that carries a 14-year jail term, so the scamming victim would believe he was helping an oppressed person, ON) “It eventually got to a point where the victim sent him money to visit in California. Then the scammer fled with the Visa fees, flight ticket, travel allowance, all of it.” Amandi felt even worse when his own aunt fell victim to a business scammer. “She lost money from the business she worked for as the company accountant. She thought she was engaging with a third party in good faith and in the end, she took the fall for it. I believe there are consequences when one does things like this.”

Nigerian cybercrime law Section 419 clearly states that internet scamming is a felony. The boys who spoke to me might go to jail if arrested. But Okechukwu Nnadi says he is not worried: law enforcement officers are also ‘hustling’, he says. “They arrest only those they don’t know or those who haven’t shown them ‘love’.” And what would be the sense of arresting him, he asks, adding that even an upright police office ‘cannot return the money to an already scammed person’. Clearly, the notion that arresting one individual Yahoo Boy would make a dent in the industry and minimise the number of victims does not seem realistic to him.

And maybe he can be forgiven for thinking that the ‘419’ industry will blossom forever. Instead of diminishing with awareness and warnings, it is growing: it has recently also extended to neighbouring Ghana, which, Nnadi says approvingly, has really ‘good internet.’

Ghana

In Ghana’s capital Accra, Assistant Commissioner of Police Afriyie Sakyi confirms he has “his hands full” with Nigerians who are “now recruiting Ghanaian young men and women, mostly in their twenties, to build a bilateral crime cartel.” Sakyi says that Ghana is fertile new territory for the Yahoo Boys because, next to good internet, it also offers credibility. It is easier for people overseas to believe in a Ghanaian ‘lover’ or potential business partner than in a Nigerian one.

A Ghanaian lover offers more credibility than a Nigerian one

Sakyi recounts how in one case a Ghanaian woman had come to his police station to report her Nigerian fraudster husband. The husband had come to Ghana from Nigeria penniless. But by smooth talking the woman, whom he married, he had managed to start using the new wife’s bank account and profile as decoy for his online ‘businesses’. He had made so much money that he had then prepared for the couple to go back to Nigeria to ‘complete a house he had started building.’ But the wife had started to fear that, once there, she would be of no use anymore to her Nigerian husband. She had withdrawn the money, the equivalent of US$ 41.000, and reported to the police. The man had then been arrested.

But such arrests have not dented the growth of the industry in Ghana. In recent years Ghanaian Daily Graphic journalist, Dominic Moses Awiah, has seen the growth of the industry in his own Accra neighbourhood. He started asking around when he noted that Nigerian and Ghanaian young men appeared to be living an increasingly lavish lifestyle in the area. He found that the ‘boys’ had morphed their scams to fit the new country, using Ghana’s much-desired gold resources (gold accounts for nearly 48 % of the country’s revenue) as bait. Fake yahoo companies would offer ‘Ghanaian gold’ to prospective ‘business partners.’ Awiah’s neighbourhood Yahoo Boys told him they received the moneys through corrupt bank staff on a ‘yahoo-yahoo’ payroll, or through MoneyGram or Western Union.

An oath of silence

At one point, he says, one of his sources offered him a bundle of notes from a box containing a million dollars in cash, if he would join the Sarkawa, the Ghanaian name for internet fraud. It was his first time seeing a million dollars, he would recollect later. He declined nevertheless.

In articles he wrote for the Daily Graphic he would later note how the criminal syndicates were using voodoo, invoking demonic powers, to bind all involved to an oath of silence to protect the practice against discovery and law enforcement. Yahoo Boys, he wrote, would tell each other stories of terrible things that had happened to those who had broken the oath.

“Nigerian law enforcement is too sickly and weak to bring political and private criminals to book”

Nigeria is yet to establish an institutional framework to fight cybercrime. Doing this is urgently suggested by T.G. George-Maria Tyendezwa, head of the computer crime prosecution unit at the Nigerian ministry of justice in a paper on legislation on cybercrime. But that anything in practice will happen is doubtful. Writer and commentator N.M, Bassey voiced the concern of thousands in Nigeria when she pointed out in a tweet recently that “The sad truth is that Nigeria’s anti-corruption/law enforcement apparatus is too sickly and weak to cope with the task of bringing political and private criminals to book. Everyone knows this.’’

Olivia Ndubuisi is a Nigerian broadcast journalist who loves investigations. She did this story in the context of the Thomson Reuters Foundations' Wealth of Nations programme.

Note: Names of interviewed ‘Yahoo Boys’ have been changed.