A transnational investigation in Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Kenya and the DRC by the African Investigative Publishing Collective

Ivory Coast chapter

“You won’t find anyone talking to you about these programmes,” says Amadi Sidiné, whose shop alongside the main road in Duékoué, among the street’s many vegetable stalls, sells everything from cans of tomatoes to light bulbs. “You can’t overcome this feeling of fear.” Duékoué is the main town in Ivory Coast’s war-damaged western region earmarked for dozens of donor-aided ‘reconstruction and development’ projects, the very programmes Sidiné is talking about. “They can threaten you, abuse you verbally and physically, or talk to your employer.” Such feared retaliation would befall anyone who would blow the whistle on the misappropriation of development aid, he explains. “If you manage to get anybody to talk about that, your article will become a work of reference.”

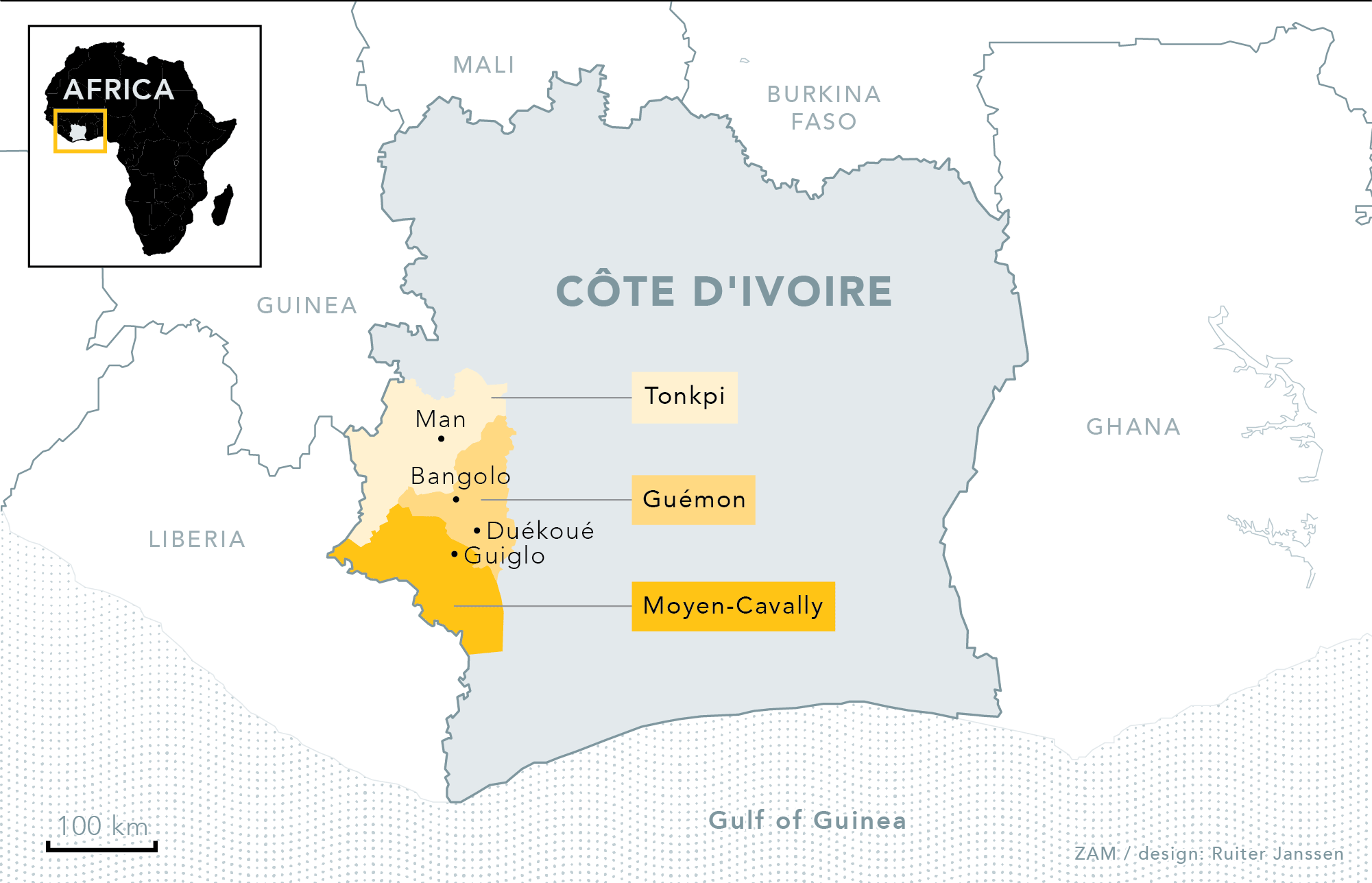

The challenge of getting information on the whereabouts of the thousands of millions of dollars that have officially been pumped into this region after civil war ended in 2008, had already become clear to me when two acquaintances who work for NGOs had mysteriously gone AWOL when I had wanted to talk to them. And after a few days travelling around in the region, from Guémon and Tonkpi to Moyen-Cavally, and trying to speak to locals in Man, Guiglo and Bangolo as well as Duékoué, I had begun to feel decidedly uneasy about the widespread reluctance of people to talk to me about the projects that they were the intended beneficiaries of.

It was clear that hundreds of NGOs, foreign aid agencies and two multibillion dollar World Bank- and donor-aided government programmes so far hadn’t improved much in people’s daily lives. ROSY PICTUREIvory Coast household surveys show a drop in poverty in the West from 67,8 % in 2008 to 56,1 % in 2015. But the most likely explanation for that is that many poor people simply went into exile after the civil war ended in 2008. The opposition has called for a boycott of such ‘political and hasty’ rosy-picture-surveys. The government has said this call was “punishable under the law.” Most people still didn’t have clean drinking water. Or jobs. Or help with their near-starvation subsistence farming. The reports published by government, World Bank and the different independent NGOs, which displayed numbers of thousands of houses built, thousands of village pumps in good working order and “over 16 000 war-traumatised youth now gainfully employed in public works projects (1),” were all the usual shiny PR, without much to show for it on the ground.

I had expected that. Pumps break down, jobs are temporary: it is the story of NGO projects all over Africa. Even the fact that much-advertised donor-funded housing for 30 000 returning refugees had materialized in the form of only a few hundred brick shelters, most of which were unoccupied and already in need of repair had not startled me. What I had been unprepared for was the silence. The atmosphere was almost as if a mafia had imposed an ‘omerta’ oath on the entire region.

58 out of 60 development aid contracts were illegally awarded

Enormous pressure

Local journalist Sehi Beh explains that locals fear the “state officials” who have cornered the development aid contracts “to deliver goods or services through their own companies, then get the projects done in their areas of origin, instead of where the needy populations are.” Hermann Francis, a former human resource officer with the Adventist Development and Relief Agency ADRA in Duékoué , tells me that senior government employees used to exercise ‘enormous pressure’ on him to get the NGO’s jobs and deals. “Requests (for jobs for themselves or friends or relatives) would come whenever we posted job ads, to employ relatives and friends of such senior civil servants.” Francis says he habitually refused their requests.

But many local projects, fearful of those who hold state power, do recruit the ‘protégés.’ A 2014 audit by the Abidjan-based headquarters of ANRMP (National Authority for Public Procurement Regulation) (2) confirms that illegal awarding of aid contracts is widespread: 58 out of 60 public contracts over the period 2011-2013 were awarded without prior publication. ‘‘[…] in 95% of all cases, the reasons adduced for such practices (were) unfounded,’’ the report said.

The government anti-corruption agency, the ‘High Authority of Good Governance,’ (HABG) says they are “fully aware of the scope of the problem.” “We urge the populations to denounce any act of corruption or mismanagement of funds allocated to development projects. To this end, we even set up an online platform that allows anonymous submissions,” says HABG official N’Guessan N’Dri.

But chances of that happening seem slim. “Who should we report corruption to? Authorities don’t care anyway; they wouldn’t do anything and it wouldn’t make a difference. They will overlook the crime because they are given bribes,” says Duékoué resident Flan Mathieu. And local pastor Oboué Armand thinks that locals will still be ‘too scared’ to talk, even if offered to so so anonymously. “They all see how elite and officials distort the system to their advantage. But community leaders are enticed or pressured to excommunicate the snitch.”

The young man faced the wrath of the community

It had happened, he says, to a young NGO worker who had exposed the appropriation of a GAVI alliance vaccination project by politically connected officials. More than a third of the one-and-a-half million US$ for the project had been siphoned off to fund non-existing companies that were fronts for individuals in government. But talking about it had led to the donor investigating, and eventually closure of the project. Some people lost jobs, other services provided by the project were suspended and local community leaders lost out on their ‘cut.’ Armand: “In the end, the young man faced the wrath of the community. He was seen as disloyal and suffered countless humiliating verbal assaults. No one wanted to listen to him.”

Big men squabbling

Some say that wastage of aid, or even corruption, is inevitable and that the parts that do reach ordinary people still have a positive effect. But what happens when aid moneys, instead of being “wasted,” are further enriching those who are already rich? What if the extra wealth gives more power to oppressive and abusive elites? A critical online article about the Presidential Emergency Programme (Programme Presidentiel d’Urgence, PPU) that did some public works in the region between 2011 and 2015 with support by the Agence française de développement (AFD), says it enhanced the power of President Ouattara, who “was seen to be making all these generous donations personally.” Quoting government sources, the article also says that the programme built unaccountable power over regular government structures for a trusted clique of the president. It characterized the PPU as “an enormous budget being squabbled over by a set of very big men (3).”

Meanwhile, genuine community organisations and entrepreneurs don’t stand much of a chance of getting support. Firmin Blé, a former deputy-coordinator of a sports project that once operated in Duékoué, tells me that projects simply come and go. “Ours was a subcontract,” he says. “And it’s over.” Retired secondary school teacher Claude Gbato, who has seen plenty international projects appear and leave again, says it’s all ‘a big joke.’ “The international donors claim with great fanfare they support local initiatives but in reality they prioritise funding for (their own) western NGOs to do the projects.” Back in Abidjan, Adou Djané, a sociology researcher at Abidjan’s university confirms that genuine local initiatives are rarely supported: “When these are contracted, this is just at the temporary service of international organisations. They go into hibernation when the international aid agency goes away.”

Rosy picture

Remarkably, Ivory Coast household surveys show a tremendous drop in poverty between 2008 and 2015 in the rural West. According to the Ivorian National Statistics Institute (INS) 2008 survey, poverty in the region was then still at a 67,8 % high. In 2011, it noted a drop to 60,5 % and a further drop to 56,1 % in 2015 (4). The Ivorian government has used these statistics to laud its own and donors’ reconstruction and development efforts in the region (5).

But there may be other factors at play. In 2008, the civil war had officially been won by the dominant political elite under Laurent Gbagbo, who became president. A large number of the underprivileged ethnic group in the West -the group that had rebelled-, went into exile after that, which means that in 2011 a large number of poor people were simply no longer there. More importantly, those poor who were still there were actually poorer than they had been before. The 2015 survey mapped out that most of the 56,1 % people living under the poverty line of US$ 1,30 per day had seen their income shrink to less than half that.

The Ivorian government has been accused by the opposition of distorting statistics to present an unjustifiably rosy picture of the state of the country generally. Remarkably, it is former president Gbagbo’s party, the FPI (Ivorian Popular Front), which was dislodged from power in 2010 and now the opposition, that is the statistics’ institute most vociferous critic. It has called for a boycott of all the surveys conducted by state agencies, calling them ‘political and hasty,’ an also unfair for the government to conduct such surveys when a large number of Ivorians are still in exile (which was the case in 2014, when the research for the survey was done.)

When the positive figures about the poverty decrease were released, the FPI and its allies accused the government of inflating the figures and lying to Ivorians and donors about the true costs of living in the country and the poverty rate. In response, government spokesperson Bruno Kone, declared that it was “punishable under the law” to “incite the citizenry to boycott” the population census.

Click here for the other country reports: Cameroon, DRC, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Uganda

- www.documentcloud.org/documents/3859339-PAPC2013.html

- Audit 2014 http:/news.abidjan.net/d/9173.asp

- www.civox.net/Programme-presidentiel-d-urgence-A-quoi-servent-les-ministres-de-Ouattara_a3640.html

- www.documentcloud.org/documents/3859435-Ivory-Coast-ENV2008.html; www.documentcloud.org/documents/3862907-Ivory-Coast-ENV2011.html; www.documentcloud.org/documents/3862908-Ivory-Coast-env2015.html

- It must be borne in mind that the surveys are usually funded by donors and also that the state officials who count the surveys may feel pressure to report positive developments. “Donors want to see results” is an often used phrase among those who are tasked with reporting on development projects. The Post Conflict Assistance Plan Survey (PCAP) of 2013 by the INS is an illustrative case. The team, tasked to survey the ‘satisfaction rate’ of citizens with regard to construction projects implemented by the PCAP, found 28,6 % of respondents in the western region “completely satisfied.” But it put 69 % of respondents in the category ‘partially satisfied,’ without differentiating between ‘very little’ or ‘a lot’ satisfied, finally listing only 2,4 % as “not satisfied at all.” In other regions, including the equally affected north, the number of ‘partially satisfied” people amounted to over 75 % (In Tanda, north of Abidjan, it was 100 %.) According to the introduction of the survey, the exercise was paid for by the PAPC itself and PAPC management also formed part of the survey’s terms of reference and management units.