Increased EU imports place South African coal mining on steroids

On 13 March 2025, at the European Union-South Africa summit in Cape Town, EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen pledged another €4.4 billion to “supporting a clean and just energy transition in South Africa”. Meanwhile, EU companies are sourcing eight times more coal from the same country than they used to in partnership with local companies that are digging up -and poisoning- entire provinces. An investigation.

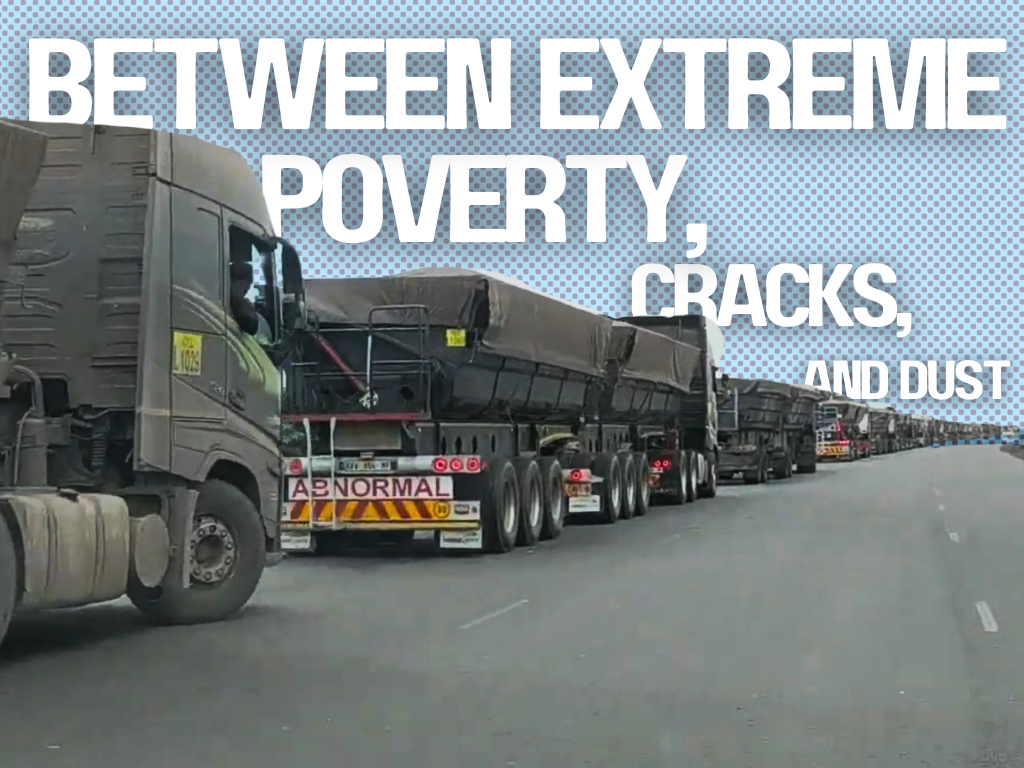

Soot-stained juggernauts packed with coal grind to a halt along the N2 highway into Richards Bay, a once-idyllic fishing village and laid-back surf resort. The static tailback, made up of hundreds of articulated lorries, stretches for kilometres into the distance, with the once-green wildlife flanking the main road now ashen and obscured from sunlight. Much of the coal in these trucks is destined for countries in Europe, part of a coal rush bonanza that stands to stain the EU’s energy transition and undermine the global race to curb climate change.

South Africa’s giant coal mining industry has been buoyed by a massive increase in demand from Europe following the Ukraine War, with European countries suddenly importing eight times more coal from South Africa almost overnight, and with coal prices skyrocketing by 130% and creating renewed interest in this archaic fossil fuel.

Coal dust

Without a mask, the grit collects and grinds against your teeth within minutes. The woman selling bunches of bananas to the immobilised drivers has a scarf wrapped tightly around her face to block the dust. Residents we speak to complain of breathing difficulties and other health issues, as well as pollution and property damage, with coal dust covering their homes and disrupting their lives.

The devastation in Richards Bay is just the beginning of the problems that coal exploitation, now intensified, brings to South Africa. Following the trail of trucks and trains back from one of the world’s largest coal terminals uncovers a desperate world marred by high suicide rates, unemployment, pollution, and misery. In the coalfields of this region, spanning the Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces, life is cheap, and water can be poisonous.

Life is cheap and water can be poison

Angus Burns, an activist working for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and based in the KwaZulu-Natal town of Newcastle, says there is currently a “smash and grab” for coal, with both people and wildlife caught in the crossfire. “Coal is a sunset industry,” he says. “This is an opportunity to make money quickly before it becomes less desirable. Raw acid now flows from springs. It is pure poison—everything that flows out is red, and nothing lives in it. You can’t drink coal.”

Drownings

Locals in Mpumalanga’s commercial town of Ermelo say that several people, including two children in one day, have drowned in an abandoned coal mine, where even the cost of putting up a fence or sign is something the mining companies seemingly cannot afford. Standing at the water’s edge, local activist Given Zulu says the temptation to swim here on hot days is too great, with tragic consequences. “Animals [also] fall in and die, and their carcasses rot—the stench is unbearable. There has to be a rehabilitation fund, but even that wouldn’t fix the damage. We do ask if someone can put a fence around it, but suddenly we find the mining company has been liquidated.”

Neither the municipality, the province, nor the national state appears to be addressing the situation. A 45-page report by Human Rights Watch, titled The Forever Mines: Perpetual Rights Risks from Unrehabilitated Coal Mines in Mpumalanga, South Africa, confirms that abandoned coal mines in Mpumalanga province have not been properly rehabilitated, and the government has failed to make progress in addressing the associated risks of injury and death, as well as the pollution of local water sources.

“The poverty is traumatising and leads to suicide”

In Phola, another Mpumalanga town surrounded by mines—including Klipspruit, an opencast mine owned by Seriti Resources that largely supplies European markets—the suicide rate is worryingly high. Phola is a mixture of orange mud, pick-ups, tired-looking mine workers, and piles of garbage. The deaths here, says the softly spoken Nkosana Mavuso, a local youth activist who started the “MP Rise Podcast” (MP for Mpumalanga) in the hope of shedding light on the town’s complex problems, are linked to extreme poverty.

"[The suicide cases] are mostly 18 to 35-year-olds—one of my friends took his own life just two months ago," he explains, speaking slowly during an interview in the back of our rental car. "Poverty is the cause, and people here are not employed. It’s traumatising and leads to suicide." There are no corporate social responsibility projects to make the environment more liveable. "The mines do nothing." Landing just a digging job in the coal mine is often the best future prospect young people in this region can hope for—never mind that the poisonous dust kills, too.

Coal imports from South Africa to Europe increased nearly eightfold, from 2 million tonnes in 2021 to 15.8 million in 2022, says The Coal Hub, the coal industry’s website portal. However, according to Reuters, that figure dropped to 3.54 million tonnes by 2024, still representing a 77% increase over 2021. The maritime industry’s BSSC cluster portal, a member of the European Network of Maritime Clusters, shows that the European Union was named the fifth-largest seaborne importer of coal in the world last year. Ships carrying South African coal regularly arrive at major European ports such as Rotterdam and Hamburg, transporting hundreds of thousands of tonnes to fill the gap left by Russian energy sources.

The minerals energy complex

In South Africa, coal is a significant part of "the minerals-energy complex," which, according to coal researcher David Hallowes at the South African non-profit GroundWork, has shaped the country’s development over the past 125 years. "The policy of providing what was called 'cheap and abundant power' to energy-intensive industries was historically based on cheap coal, cheap labour, and heavy pollution," he says. "It has resulted in a highly concentrated economy with extreme inequality, and one of the most energy- and carbon-intensive economies in the world."

The president has mining interests

Coal is also deeply connected to the ruling party in South Africa. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s billionaire brother-in-law, Patrice Motsepe is the founder and Executive Chairman of the major mining company African Rainbow Minerals, a shareholder in the Richards Bay Coal Terminal, and the Founding Chairman of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Business Council. Motsepe is also the President of the Confederation of African Football and Vice President of FIFA.

The South African president himself, reportedly one of the country's wealthiest politicians with a net worth of about US$450 million, has, according to sources including the BBC, accumulated vast wealth from various industries, including telecoms, media, restaurants, and mining. President Ramaphosa was also a director in Lonmin, the multinational that owns the Marikana platinum mine, when police killed 34 striking workers in August 2012.

Organised crime

Moreover, while progress has been made in the areas of human rights and social justice under South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress (ANC)—which Ramaphosa also leads—the ANC-led state in the minerals-rich country has also become corrupted by politically linked business cartels, particularly in the coal sector.

A 2022 report by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime mentions that a key factor in this is “the enduring legacy of apartheid, both in spatial and socio-economic terms, which has created space for criminal governance, most notably in the form of extortion.” The report claims that South Africa is witnessing a ‘dramatic expansion’ and ‘legitimisation’ of extortion across a broad spectrum of society, revealing that “criminal actors become increasingly organised and strategic, forming cartels, expanding portfolios and reinventing themselves as business entities.” Another report, by Corruption Watch in 2024, stated that more than a third of corruption complaints registered in 2023 were related to activity in the mining industry.

The cartels have tentacles in the political leadership

The influence of mining cartels, which typically care little for safety or the environment and have many tentacles in political leadership at all levels, is tangible in provinces like Mpumalanga. Mining analyst and academic David van Wyk, lead researcher at the Bench Marks Foundation—which “examines corporations from top to bottom on their social, economic, and environmental performance within a sustainability framework”—says, “A lot of Mpumalanga looks like a dystopian nightmare,” adding that “It is a syndicated criminal economy, with syndicates in mining, but also in human trafficking and the car industry.” Van Wyk strongly believes that steps should be taken to reduce the influence of cartels: “Regulate the economy properly, and the syndicates will disappear.”

Cracked houses

Almost 280 km south of Phola, in the adjacent province of KwaZulu-Natal, is Dannhauser. According to the Centre for Environmental Rights, in 2021, community activists protesting against the impacts of the local Ikwezi coal mine, including damage to residents' houses, were reportedly shot at and arrested. Resident Themba Khumalo, who lives near the Kliprand Colliery, says he still has cracks in his house, but his complaints to the mine went unanswered. “I, like others, was told the house was not built by the correct constructor. So it is our own fault,” he says. He adds that exporting coal from South Africa to places like Europe does not help these communities. “People are dying while others benefit from coal. We prefer life over coal.”

The holding company sells to sixteen countries

Ikwezi Mining, which operates the Kliprand Colliery, is part of Oza Holdings, based in Midrand. Another part of Oza Holdings is Zorba Coal, an integrated coal company that exports from Richards Bay DBT/MPT to over 16 countries across Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South America.

Another local activist facing repercussions for fighting the mines is Mandy Austin, who tells us of “being tracked and receiving threatening calls.” “It’s all meant to stop our fight against pollution, cracked houses, and livestock dying.” As the town is now at the centre of a new coal mining project, the Newcastle Project, which consists of a prospecting right for coal over various farms west of the city, covering approximately 3,250 hectares in total, Austin has set up seven WhatsApp groups for locals. These groups have ballooned to over 2,000 members in the last two weeks—reflecting the number of people here who fear damage to properties that many have spent their lives paying off. “Local residents know this means the end of our town’s infrastructure,” says Austin.

Close to the water

Wildlife activist Angus Burns agrees that the expected damage justifies continued efforts to stop the mining. New mines set to begin include one on a hill that is home to a wide variety of flora and fauna, and is located near thousands of houses. Regarding the dam, the town's only water source, he explains, "The plans are very poorly thought out." He adds, "There are mines and applications all around it, directly threatening our water supply."

David van Wyk adds that it is a contradiction for Europe to increase coal imports at the same time it is pledging ‘green’ billions to South Africa with the goal of reducing domestic reliance on the black fossil fuel. "Looking for renewable energy but demanding coal on a huge scale" is a global paradox, he says. "People ask why the government is exporting so much coal, with coal going to Europe and the Middle East. Those places seem to be developing, while we are not. Why are they pushing this transition on us and not practicing what they preach?"

The green billions are a paradox

Ukraine

With landscapes in Mpumalanga and further south in KwaZulu-Natal already devastated, Sandy Camminga, director and founding member of the Richards Bay Clean Air Association, which monitors and tracks pollution, points out that the pollution problems in the northern area of Richards Bay did not exist before Europe increased its coal imports from South Africa. "The influx [of trucks] started when the Ukraine war began," she says.

Camminga has also observed an increase in health problems recently. “People talk of scratchy eyes and coughing. This is disastrous from an environmental perspective. People are making huge amounts of money and destroying our city, while the money from exports is not returning to the community. For people here, there are no positives, only negatives.”

“For people here there are no positives”

Amid empty holes and devastated landscapes, more mines are still being planned in this region and across South Africa. According to our analysis of the Global Energy Monitor’s Global Coal Mine Tracker project (April 2024), there are 82 operating coal mines in South Africa and 35 proposed coal mines, six of which are already under construction. The proposed mines would add nearly 63 million tonnes per annum to Mpumalanga’s coal production. Angus Burns notes that there are now many small operators who make a few million from coal before disappearing from the industry. “Mining has exploded all over the place, and we are trying to understand what drives it, but Ukraine is definitely one of the drivers.”

Giving back

When asked to comment, mining company Seriti Resources stated that it has initiatives aimed at "giving back" to local communities, such as the Monyetla Free Wi-Fi project for the Phola community. However, despite this, no action appears to have been taken by Seriti in response to the April 2024 protests, during which community members called for additional material support, employment opportunities, and an assessment of the damage to their homes caused by blasting.

In response to further questions, a spokesperson for Seriti stated that the company "remains compliant with the conditions of its mining rights" and has established a Community Trust, where communities hold a 5% shareholding. The trust is registered with the Master of the High Court and "serves as an additional vehicle for community benefit delivery." The spokesperson added that "Seriti engages with all interested and affected stakeholders through its Community Consultative Forum," that it "upholds all applicable laws, regulations, and industry standards," and that it has "robust systems in place to ensure compliance across all aspects of the business."

The CEO thinks coal has a long future

The spokesman also stated that the company recognises "the science of climate change" and the importance of decarbonising the economy, as well as "a South Africa that is less reliant on coal." "But we are very conscious that this needs to be done in a way that does not destroy our industrial base or the lives of South Africans who rely on our companies for jobs, enterprise, and support."

July Ndlovu, CEO of Thungela Resources—one of South Africa’s biggest coal miners and a major shareholder of the Richards Bay Coal Terminal—believes coal has a long future. This is perhaps unsurprising, as Ndlovu is also the chairman of the World Coal Association, a controversial pro-coal lobby group made up of some of the world’s largest fossil fuel beneficiaries. “Many often perceive coal as a relic of the past, but I propose a different perspective,” Ndlovu told the Mintek@90 Conference of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy in November 2024. “Coal is, in fact, a cornerstone of modern energy resilience.” A Thungela spokesperson said they were not in a position to comment.

A Just Energy template

In this region, one feels a world away from the US$8.5 billion Just Energy Transition (JET) programme, signed by some of the world’s wealthiest countries in 2021 to help South Africa become less dependent on coal. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the EU Commission, has described how JET would become a ‘template’ for decarbonising countries worldwide. But in South Africa, local environmentalist Philani Mngomezulu, speaking from Mpumalanga’s Ermelo, says, “The idea that Just Energy is moving away from coal – it’s just an illusion. We are mining just as much as ever. These precious commodities are moved around to benefit a small group of people, while the local community receives nothing.”

Mngomezulu is the founder of the Khuthala Environmental Group, an established community-based greening project in Ermelo that runs a small farm and grows spinach. He points out the irony: "This is a town surrounded by the impacts of coal mining, yet you see local people climbing up electricity pylons to connect their homes to power using DIY cables. There is fuel for electricity everywhere, just not in the townships that suffer from it." He adds, "A lot of people are in the pocket of the mining sector. When it comes to energy, loads of foreign companies are moving in – This is modern colonisation."

“This is modern colonisation”

Asked about measures to ensure that coal reaching Europe comes from ethical and non-destructive sources, an EU spokesperson cited the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), stating that “companies must report on, amongst other things, actual and potential adverse impacts on people and the environment in their supply chains.” The official added that while there are “no specific provisions on coal or on ethical coal as such,” any company reporting under the CSRD and importing coal into the EU would be required to disclose “whether and how it has addressed adverse impacts caused by the mining of that coal, if it considers those impacts to be relevant.”

Inquiries and phone calls to South Africa’s Department of Minerals regarding efforts to combat corruption in the mining sector and prevent pollution and environmental destruction went unanswered.

A new post from Mozambique and Malawi shows that, in that region too, ‘green funding’ is pocketed by leaders while citizens remain without energy and exploitation of natural resources continues. Read it here.

(1) Blasting involves the use of explosives or high-pressure techniques to break rock in preparation for excavation.

This article was supported by Journalismfund Europe