When the force isn’t with you: one community’s fight for the light it needs to live and trade.

Temitope Meshach, who runs a bakery in South Ondo Senatorial District, Ondo State, Nigeria, has a mixer and oven that can produce four cakes at once. However the heavy equipment requires an adequate electricity supply to function, and she has not been able to use them since the lights went off in her area ten years ago. ‘I have a generator but the capacity is not enough’, she says, adding that the same goes for the freezer that used to keep her supplies fresh. ‘All that equipment is fast decaying. Small tools still work with the generator, but it is expensive. I spend about 3,000 Naira (7 US$) daily to power the generators at my home and office.’

Likewise, Damilare Ojomo, a businessman along Broad Street in Okitipupa, said he had to give up on his former trade of supplying ice-blocks to street traders who needed it to cool their fizzy drinks. "I made a lot of profits because I had electricity to power my freezers and sell enough products. There is no way I can power the freezers with a diesel generator.’

Glass and palm oil

Meshach and Ojomo are just two of the two million inhabitants of Ondo South Senatorial district who, in the decades after independence, benefited from the bustling business and economic growth. They, like community leader Michael Asogbon, remember the days when a glass factory in the region supplied every part of the country with locally-made glass sheets and a palm oil factory attracted foreign investment to the area. ‘There was full employment, attracting people from other parts of the country’, Asogbon says, but ‘now the industries are moribund or have left, and small scale businesses are struggling to survive. We have ghost communities where people can no longer afford to live in darkness."

The lights went out in some districts seventeen years ago, while in others it was eight or ten years back. The exact reasons vary depending on who you listen to but it’s a mix of unpaid bills, failing infrastructure, a lack of clear management and accountability and, perhaps most importantly, state and company fraud. But so far no governing body, from the electricity distribution company to the electricity regulator, the Rural Electrification Agency, the Ondo State government and the national leadership, has been effectively held to account for this crisis.

Communities call out to authorities to ‘bring back our light’

What the darkness has given birth to, however, is an increasingly united and combative populace. Citizens have formed the Bring Back Our Light (BBOL) movement which, in the words of its convenor, pastor Pastor Olumide Akinrinlola, ‘protests, confronts and lobbies through influential Nigerians’ to get the issue resolved. Akinrinlola recalls how in his area the lights went off without warning in December 2014, in the midst of preparations for the Christmas festivities. The community was later informed that the Benin Electricity Distribution Company (BEDC), the fourth largest power supplier in the country, had cut them off over alleged unpaid bills of about N2 billion, or US$4,5 million.

Crazy billing

There was no way this was plausible, says Akinrinlola. ‘For example, some communities in the district had not enjoyed electricity supply since 2005 and they were still billed too, and then these bills were added to the indebtedness of our communities. In the end we compiled and submitted the billing history of communities who had been without electricity supply for the past ten years. Our findings revealed that electricity consumers in one particular area, Ilaje, alone had up to the same amount, N2 billion, credit balances with BEDC. This meant that the BEDC was indebted to consumers (instead of the other way around) even before the cut-off. Our report was submitted to the local government chairman, with a copy submitted to the BEDC office and the state government.’

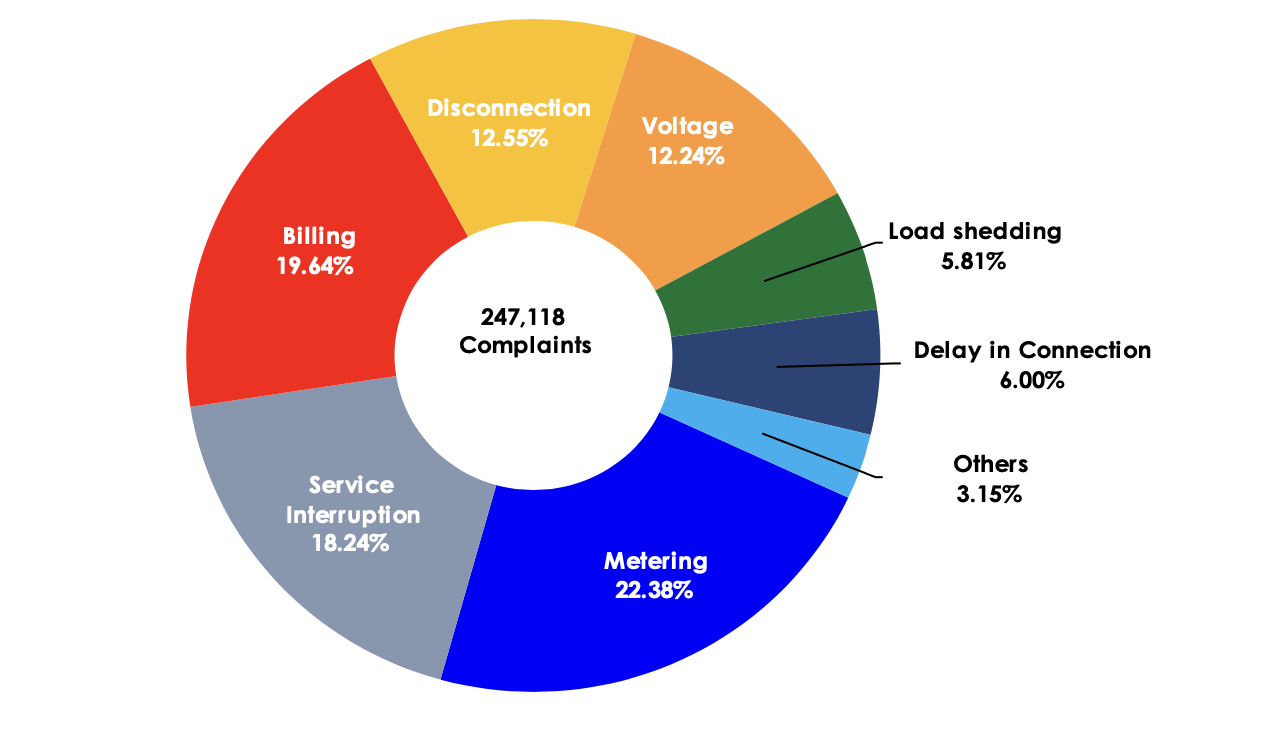

This may be in part as a result of what is known as ‘crazy billing’, a common Nigerian term for estimated bills. This system is used in many parts of the world and it often works well, but in Nigeria the estimates are not confirmed later by checking the meter. This results in bills of unreasonably high amounts. But, says Akinrinlola, the billing was only part of the problem. ‘There was also damaged equipment on the BEDC’s side, both in the areas that were cut off in 2005, and in ours. When we offered a debt payment arrangement, the BEDC said that their electricity transport supplier, a company called TCN, could not deliver the power to our district.’ The lights stayed off.

Since then the population have made several efforts to get the BEDC to reconnect them, including protests and petitions to government agencies and officials, but these have all come to nought. Even when Ondo State’s then-Governor Olusegun Mimiko waded into the matter, the ‘peace meeting’ brokered by one of the local chairmen turned out to be a waste of time; the BEDC still demanded full payment of their alleged debts, while community representatives rejected the figure as ‘outrageous.’ The current governor, Rotimi Akeredolu, later made several promises to put an end to the darkness, but nothing has materialised to date.

The electricity company failed to pay its own debts

An underlying cause of this protracted chaos seems to be the privatisation of the BEDC, which was formerly a state company, in 2013. As part of the privatisation exercise the electricity distribution company solicited loans from a consortium of banks in Ondo State but, in an ironic twist, failed to pay its bills. The banks then started litigation with the intention of seizing control of the BEDC. Residents suspect that this is part of the reason for the BEDC’s excessive demands for money.

‘Fraudulent and unacceptable’

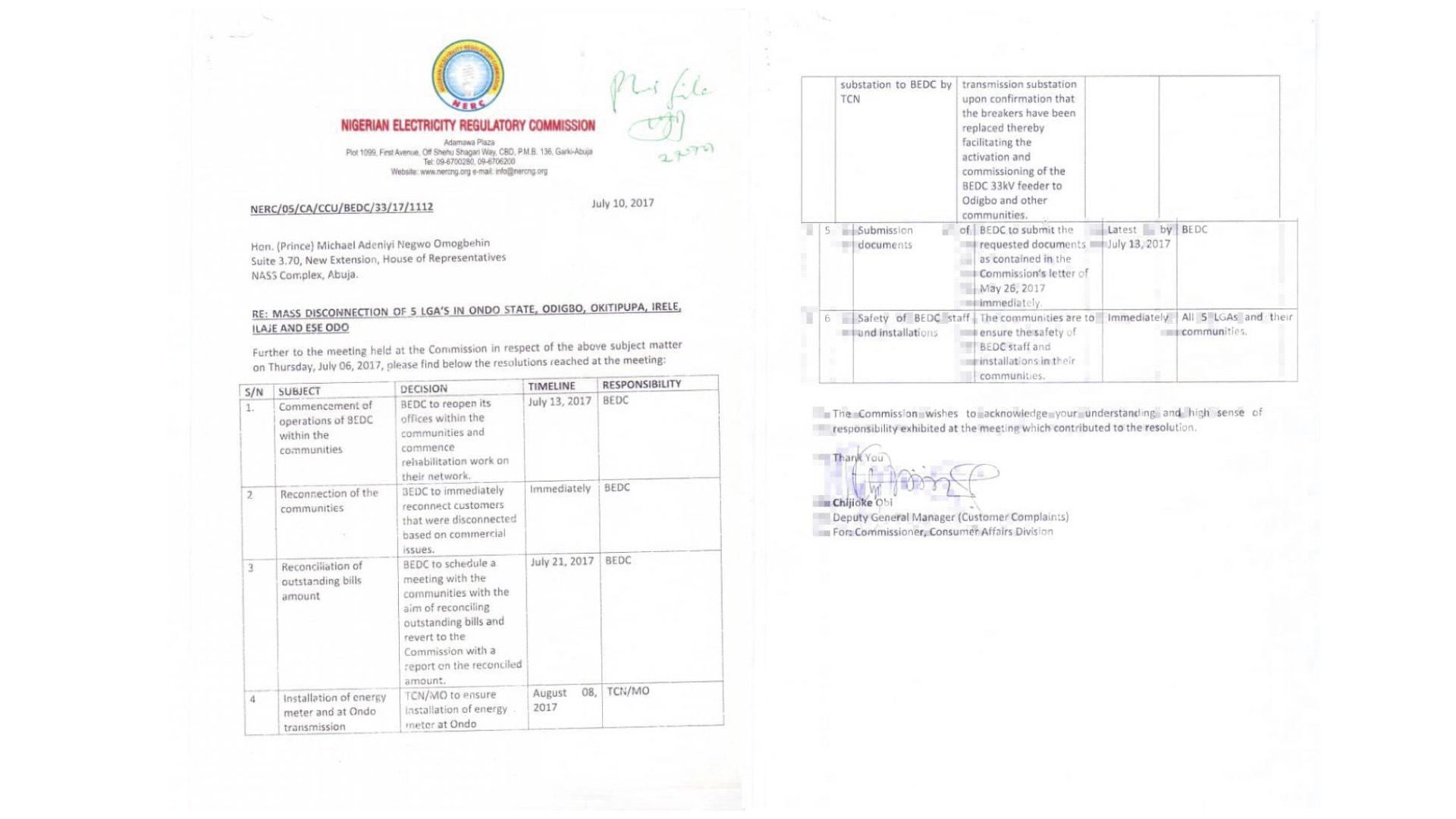

In 2017 the residents’ campaigning finally seemed to be getting somewhere. Under pressure, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) called a meeting of all the stakeholders, including the top management of BEDC, at their offices in Abuja on July 6, 2017. According to BBOL’s Akinrinlola, his group presented the meeting with documentary evidence that the district was illegally disconnected. NERC later passed a resolution directing BEDC to 'resume work and reconnect the affected communities immediately, and that two weeks thereafter both parties should reconcile the disputed debts’. When the distribution company flouted the directive BBOL stepped up their tactics. In 2018 they dragged the company to the federal presidency, where vice-president Yemi Osinbajo made it clear that he supported the NERC directive. He also approved funding for the rehabilitation of all the damaged electric cables, which were duly renovated.

This was still not enough for the distribution company however, which continued to refuse to connect the district. It declared that it would only reconnect its customers on the condition that it could continue issuing estimated bills, and the communities rejected the terms. ‘We have resisted every attempt by the company to restore electricity through an estimated billing system,’ says Akinrinlola, ‘because it is fraudulent in nature and unacceptable.’ Instead, BBOL asked for prepaid meters. ‘The company only issued a few, resulting in just an inconsequential fragment of the people now re-connected. But more than 95% of communities in the district are still in darkness because of BEDC’s refusal to provide enough meters and finish repairs in some areas.’

A budget for the ‘restoration of light’

The government, meanwhile, made efforts to get at the problem sideways, though these attempts failed. In 2017, Nigeria’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA), which is responsible for bringing electricity infrastructure to rural areas, budgeted about N53,3 million (US$130,000) to restore power supply to some parts of the South Ondo district. The area, which is made up of five local governments areas, Okitipupa, Ilaje, Ese-Odo, Irele and Odigbo, had been cut off from the national grid by the BEDC in 2014. The REA’s project budget included funds and labour totalling N30.8 million (US$72,000) for the installation of solar street lights and transformers, as well as N22.5 million (US$52,000) for an item simply called ‘restoration of light to Okitipupa/Irele’.

The two lights had worked for two months

REA’s performance report on the projects, which we obtained through a Freedom of Information request earlier this year, is quite positive about its own results. It states in part that all the projects had been awarded, the funds disbursed and the resulting work "completed as awarded", with some projects even being marked as "100% completed”. However a quick tour around the district reveals that what is written on the report bears little resemblance to the reality on the ground.

Take, for example, Laraba Crescent and Bamido Street in Igbotako, where a N11,6 million (US$27,000) contract for the provision of fifteen solar street lights was formally awarded in January 2018 to a contractor called Island Expose Limited. Despite the project being marked in the REA’s report as ‘Completed’, a short walk along the roads found only two poles installed, neither of which was working. A local resident also confirmed that the lights had worked for a few months after installation before failing.

Other projects marked as ‘completed’ in the REA report could not be identified because no specific location was provided in the report, but repeated inquiries in the areas where work was supposed to have been done failed to identify any sites where fresh transformers or other electrical equipment might have been installed during the period under review. Contacting ‘Island Expose Limited’ was not possible because its details were withheld by REA. A request to REA to explain why a company such as Island Expose Ltd was able to win such a contract despite appearing not to have any record in the sector went unanswered.

Missing gap

‘The missing gap in these projects is that there is no specific individual or body that is legally empowered through the law to carry out monitoring and evaluation,’ explains Kunle Olubiyo, who is the president of Nigeria’s Consumer Protection Network. ‘There's no act of parliament to ensure that there is an (independent) entity that appraises the project and supervises where public funds are spent.’

When asked about the BEDC’s flouting of orders issued by regulators, Olubiyo said that ‘most of the challenges in the electricity sector can be traced to corruption in the system,’ adding that ‘we do not have a firm and incorruptible regulator in NERC at the moment. A distribution company can put pressure on the NERC and it backtracks. We need an incorruptible arbiter here, too.’ Adetayo Adegbemle, the director of Power Up Nigeria, a power regulation lobby group, agreed that Nigeria’s regulatory agencies need to clean up their act, and pointed out that consumers themselves are trapped, which is harming the economy. ‘Customers cannot pay up their bills when their businesses are not running. The regulators need to pay attention to how distribution companies are handling such issues.’

Nor the regulator nor the electricity company responded

The BEDC did not reply to emails or phone calls. We also reached out to the NERC by email to ask what measures were in place to ensure that BEDC carries out its reconnection order, in addition to asking what punitive measures the regulator has in place to deal with contractors that disobey its orders. Like the BEDC, the regulator also did not respond.

BBOL’s Akinrinlola remains hopeful that the recently-installed infrastructure, as well as a new transmission substation that is currently being constructed, will herald better times. He still holds out hope that the district will be fully reconnected ‘someday’ and that power will bring with it a return to the economic growth of the past. But that ‘someday’ feels like it’s long overdue for business people like Temitope Meshach, whose bakery can now only produce one cake a day.

Taiwo Adebulu is a multi-award winning Nigerian journalist who has received international recognition for his impactful investigative and development stories, most recently at the inaugural BudgIT Active Citizens Awards where he was announced the winner of the solutions journalism category. He is currently the features editor at TheCable, Nigeria’s foremost independent online newspaper. Taiwo holds a bachelor's degree in Language Arts from Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU) and a master’s degree in Communication Arts Education from the University of Ibadan (UI). He is a Pulitzer Centre grantee. He began his journalism career in 2014 as a freelance reporter with The Nation, Nigeria’s widest circulating newspaper. In 2020, he won the PwC Media Excellence Awards. He also won the overall prize at the African Fact-Checking Awards in 2020 for his investigative piece that exposed the falsehood of Nigeria's minister of environment, who claimed at a United Nations summit that seven federal universities were running strictly on renewable energy. One of his recent investigations, funded by ZAM Magazine, exposed the systemic corruption in Nigeria’s foremost marriage registry. The story forced the Nigerian government to reform the process.