The mysterious contracts that emptied the health budget and left patients in the cold. Using hundreds of millions of dollars to buy new medical equipment for the country’s main hospitals was presented as a good idea. It wasn’t. But those who objected were arm-twisted and run over in a process driven by ‘coercive vendors.’

On a sidewalk next to the Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi stands a weeping woman. She is holding another smaller, woman who is also crying and appears to be struggling to stand upright. They are sisters, they say: Gladys Mwihaki and Esther Wambui. Esther, the younger and smaller one, has to leave the hospital to go home since she can’t afford the hospitalisation fee of about USD 20. She has cervical cancer.

The Kenyan Constitution’s Bill of Rights says that “every Kenyan citizen has a right to the highest attainable standard level of health, which includes the right to health care services.” In addition, Kenya’s Health Act of 2017 seeks to specifically safeguard health care services for vulnerable groups, like women, the aged, persons with disabilities, children, youth, as well as members of minority or marginalised communities. So far, however, these rights exist only on paper. Most health treatment still needs to be paid out of pocket in the country.

In the following days well-wishers will scrape together the USD 20 needed to get Esther Wambui a hospital bed for the night, some tests and some pain killers. But to be treated with the chemotherapy she needs, she must pay a deposit of USD 200: more money than she will ever be able to get. At the time of writing this, Wambui remains bedridden at home, in pain and unable to sit down or move much. All that Gladys can afford at the moment is to provide food for her sister and the five children they have between them. “All Esther does is cry all night and we just don’t have the money,” she sighs. Gladys makes about USD 4 a day washing clothes for people.

Buying things

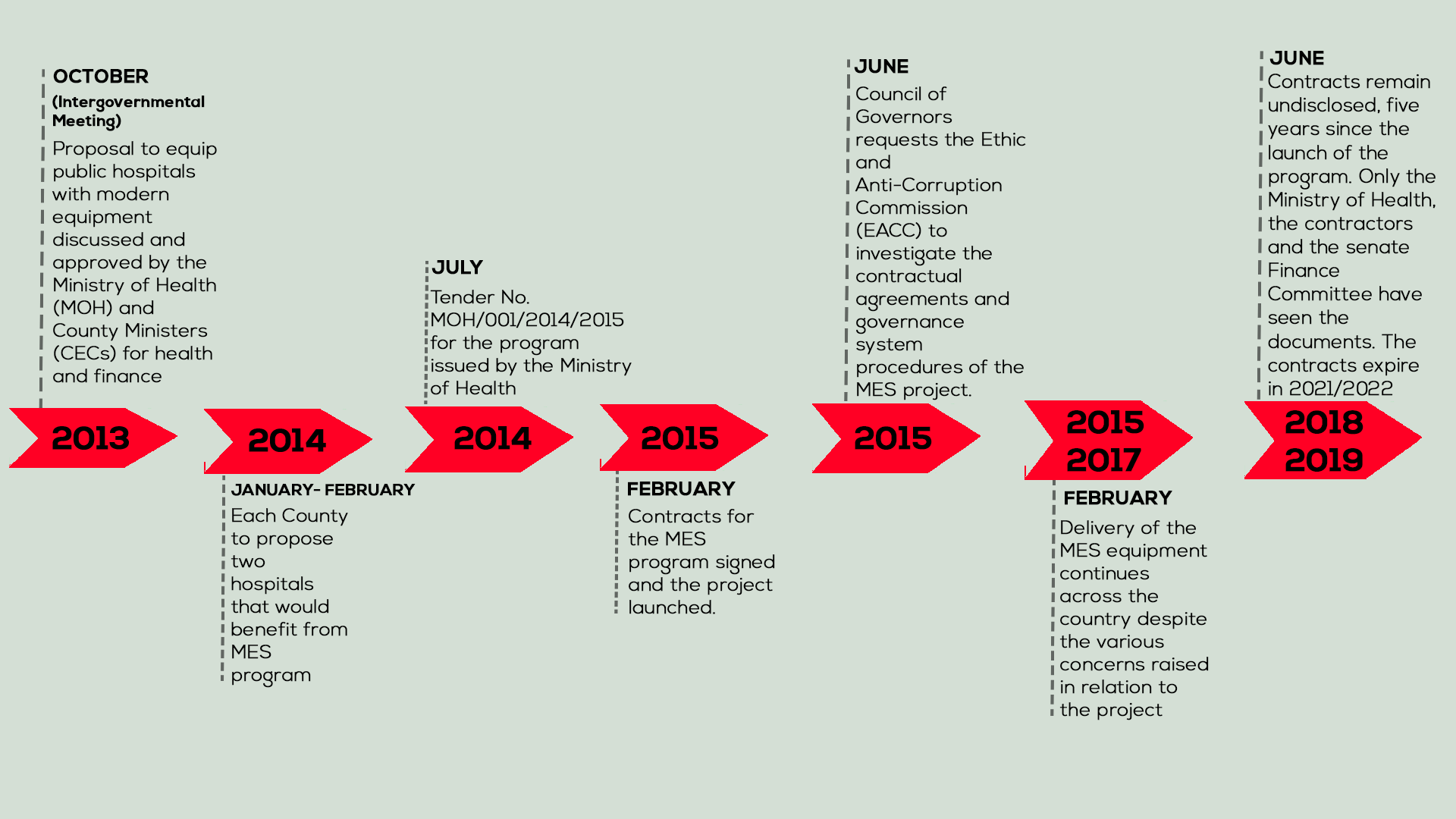

On paper, the Kenyan government tries hard to improve the situation. In policies called the ‘Kenya Health Policy 2014-2030’ and the long-term development agenda, ‘Vision 2030’ among others, it pledges to provide quality health care services to all its citizens as provided in the Constitution. In October 2013, the national and local governments (through representatives from forty-seven regional counties) came together to discuss functional and accessible hospitals, including staffing and quality of care, in the Health Sector Intergovernmental Consultative Forum.

That is where it started to go wrong. Because instead of thoroughly exercising through Kenyan citizens’ health needs, -like Esther Wambui’s need for chemotherapy- the forum immediately jumped to buying things. A proposal to buy modern equipment for close to a hundred hospitals, -a project that would henceforth be referred to as the MES (Managed Equipment Services)-, was announced by the government. MES would supply apparatus like X-ray and dialysis machines, operating tools and tables, lab necessities and intensive care beds to in total 98 hospitals in 47 counties.

Counties and hospitals were not consulted

Remarkably, according to the – now-retired – Ministry of Health head of clinical services, Dr John Odondi, successful bidders for the contracts had already been identified by then.

“At the time of the meeting, the technical and financial evaluation had been completed to determine the successful bidders and the tender processing committee was preparing an evaluation report,” the 2013 Intergovernmental Forum Committee report quotes Odondi as having said. Which means that a list of physical things to be bought -a process notorious for the opportunities it creates for kickbacks since the lucky companies can often be persuaded to share with the relevant officials- had already been decided upon by the time the discussions at the Forum took place.

The Kenyan government would later argue that they had conducted a ‘needs assessment’ with the counties before issuing the final tender, but county representatives disputed this.

Not that some equipment was not needed in the 98 hospitals countrywide, roughly two per county. But, as is often the case with big procurement packages for material things to buy, many necessities were overlooked.

To work the machines, hospitals would need trained and paid nurses and doctors, as well as the infrastructure to place the shiny new machines and instruments correctly and connect them to the needed electricity. The machines would need to be cleaned and maintained. Moreover, patients would not only need the equipment, but also a clean environment, specialist treatment and medication supply. Esther Wambui’s chemotherapy treatment depends more on specialist care and the right medicines than on a machine.

Many necessities were overlooked

Nevertheless, in July 2014, nine months after the initial forum, Tender No. MOH/001/2014/2015 to a value of 38 billion Kenyan Shillings (Kshs), the equivalent of USD 375 million, was formally issued by the Ministry of Health for supply, installation, testing, training, maintenance and replacement of medical equipment through the MES programme. Shenzhen Mindray Bio-medical of China, Esteem Industries of India, Bellco SRL of Italy, Philips Medical Systems of the Netherlands and General Electric of the USA were contracted to deliver the identified items. The contracts under the MES project were signed on 5 February 2015.

Arm-twisting the regions

The 47 Kenyan regional authorities – called Governors – who are in charge of the hospitals in their areas, were then arm-twisted into signing their approval. In a letter to the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) dated June 9, 2015, the Council of Governors said that the regional authorities “had been under a lot of pressure (…) to agree and sign the MoU (Memorandum of Understanding, JK) prepared by the National Government to effectively start the project.” They added that “the entire process has been undertaken by the national government (…) without consultation (…) but that nevertheless, “due to the pressure, the Council of Governors has agreed to sign the MoU as they await the outstanding answers.”

The pressure, the governors said in the letter, had not only come from the government, but also from a public that, desperate for better health care, hoped that the medical equipment scheme would help. “I first had refused to sign for a long time, but there was a lot of politics. People were saying “he is refusing and people are dying,” (now former) Narok County Governor, John Nkedienye, confided.

Most of the counties, however, were not given the actual procurement contracts, nor were they consulted on what equipment was needed in their regions. Checking the MoUs between central government and counties that were signed under the aforementioned pressure, Africa Uncensored discovered that each county was to purchase the exact same equipment list -regardless of size of population or hospital needs.

Hospitals now sat with stuff they had not asked for

The EACC did not undertake any action on the basis of the county governors letter, however, and the MES purchases continued.

Throughout 2016 and 2017 at least half of the targeted hospitals received stuff they had not asked for, did not need, or in many instances, could not use. The Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital in Kisumu County, for example, received seven intensive care beds even though they had just recently bought the seven beds they needed.

“We did not have enough staff (for those extra beds),” says former Kisumu County Minister, Dr Elizabeth Ogaja, in an interview. “So some remained unused.” Local media reported hospital staff sources complaining that their new CT scan or X Ray machines stood unused as well, either because they already had these or could not operate them.

In Ndanai Hospital in Bomet county, operating theatre equipment that was received in 2016 stood unused for three years because the hospital did not even have surgery facilities at the time. Former Bomet County Governor Isaac Ruto said in media interviews that he had not even signed the MoU for the deliveries, but that these were made nevertheless.

The governor had not signed but the deliveries came anyway

Still other reports mentioned that non-medical companies had come to construct new buildings, or do roofing, landscaping and painting at exorbitant prices on the orders of ministry officials as part of the MES programme. This raised suspicions that contracts with the main providers had been adjusted to include certain subcontractors -again, presumably because kickbacks could have been involved. In one case, the Kenya Standard newspaper quoted hospital staff as saying that instead of anything medical, air conditioners and office furniture had been delivered.

Lack of full disclosure

The Senate Finance Committee, in a report about the MES project issued in 2018, stated that in several cases equipment had been received by hospitals that “already existed in the facility and (was) therefore of low priority” and that this “clearly (indicated) a lack of consultation between the two levels of government.”

In the report, as part of a segment titled “Issues for Consideration”, under “Lack of full disclosure by the Ministry on the contracts” it is also stated that “Some (hospital) facility heads are not fully aware of the exact equipment they expect to benefit from. As such some MES providers are suspected to have supplied incomplete sets of equipment to facilities.”

According to Senate Finance Committee member, Makueni County Senator Mutula Kilonzo Junior, the Senate “has records to show that half of the (…) hospitals in the contract have not utilised the equipment because they do not have the (…) infrastructure, trained personnel or staff who can run the radiology and other advanced equipment that are part of this (project.)”

The Senate Committee requested Kenya’s auditor general Edward Ouko to look into the case of the MES deliveries, which he did, resulting in a series of “systemic weaknesses” found and “listed in audit reports,” Ouko told Africa Uncensored in an interview. He also said that “in some cases we have actually gone to counties when things were delivered, but there is actually nothing there or there is something but (it is) in boxes,” adding that he had requested to see the main contracts with the suppliers but that these had not (yet) been made available to him.

Senator Mutula Kilonzo Junior did get to see the main supplier contracts briefly in November last year, when the Senate’s Finance Committee summoned the Cabinet Secretary to account for the problems with the MES, but said that as soon as they had seen the documents they were taken away again. Kilonzo did notice, he said, that the contracts were not signed by the Cabinet Secretary for Health as they should have been.

Only the Senators briefly saw the contracts

Besides the contractors and the Ministry of Health, the Senators are the only ones who have so far succeeded in seeing the main documents. A request from Africa Uncensored to see the contracts has resulted in a reply from the Ministry of Health that it had “written to the Attorney General for legal advice” on the request.

Data leaked to us from the public financial management portal (IFMIS*) containing payment transactions between 2014 and February 2018, shows that up to February 2018 the total amount paid out to the contractors under the MES project was Kshs 26,033,720,377 (USD 257 million). Close to USD 27 million of this amount, was, remarkably, already paid out to suppliers Esteem (India) and Bellco (Italy) before the contracts were even signed. In the case of Chinese Shenzhen Mindray, contract and payments to the tune of USD 20 million commenced in May 2015, whereas the contract was only signed in March 2017.

Skyrocketing costs

Meanwhile, the cost for installation and maintenance of the MES equipment is skyrocketing, too. Though the regional Counties had initially been told by Government Health Secretary Sicily Kariuki that the new burden on their health budgets would come from a ‘grant’ that the central government was to make available for this purpose, several county governors and health ministers when contacted by Africa Uncensored all said they had not received such allocations and that deductions were being made from their regional budgets. These deductions had now doubled from Kshs 100 million (roughly USD 1 million) per year per county to Kshs 200 million, USD 2 million per county, bringing the total yearly maintenance budget up from USD 47 million to USD 94 million. It is a severe cut in a county where health care in many regions is already severely underfunded (see box).

Remove the politicians from health care

Beside the issue of buying wrong or unnecessary machines, the focus on the material outfitting of hospitals is also putting the cart before the horse, says former Kisumu County Health Minister Dr Elizabeth Ogaja. “Yes of course we need hospitals that work,” she says. “But if more discussion would have been allowed, we would have focused on the primary health care base and then see what we need to do to have hospitals take care of what cannot be handled at the primary health care level.”

Most health policies in the world, and indeed in Kenya, envisage that basic patient care -for conditions such as colds, flu, allergies, simple infections, diarrhea and head and stomach aches without underlying conditions, as well as the diagnosis of more severe conditions that should be referred to a hospital– should be primarily provided in communities, close to citizens. In that way, larger hospitals can be freed to provide specialist care, for example for the over 165,000 (1) people who die yearly in Kenya from diseases that (regularly or often) need more advanced treatment such as TB, pneumonia, AIDS and cancer. Esther Wambui might get the care she needs if the hospital where she sought it was not overburdened with patients who could have been treated at primary level.

“On a community health care level, counties are struggling. They need strengthening and budgets and strong policy support,” says health policy and management specialist at the World Bank, Dr Frank Wafula. “Primary healthcare in the country is only getting Kshs 2 billion (USD 20 million) altogether per year at the moment, whilst the budget for Kenyatta National Hospital (the largest hospital in the country, ed.) gets close to Kshs 15 billion (USD 148 million) annually.”

Wafula attributes the focus on hospitals to the “politicisation” of health care, where hospital building and equipping have “become something for politicians to get votes. Then, when a new politician comes in, he does not want that hospital completed because he thinks it will make the (previous) guy look good. So he starts his own. Then you have a whole lot of abandoned projects. It is just a mess.”

Asked whether patients like Esther Wambui would not also need health insurance that would help pay for the expensive chemotherapy she needs, Wafula says it is “fantastic” that, recently, some national health insurance pilots have been initiated, but that the “financial element” should not be confused with effective care. “The big problem is the (lack of) effective care. You can’t just give people a health insurance card and tell them to go to hospitals. What do people actually get when they get to the hospital?”

Emphasising again that the main challenge in Kenya is to remove the management of health care from “the political process and people who are looking for political survival,” Wafula explains that it is only then that the national government will be able to “manage the large hospitals and the specialised services (properly) centrally and also support the decentralised primary health care levels and give them enough budget.”

A severe extra cut was made to the regional health budgets to pay for the MES

The increase was partly, according to the government Health Secretary who had been quizzed about this by the Senate Finance Committee, because twenty-one more hospitals had been included as recipients of MES equipment- again without consultation with the counties. Senator Mutula Kilonzo Junior expressed his concern about the expansion and further deductions, saying that “The contract was fixed (and that) the variation to increase the hospitals (…) has no basis.”

Uasin Gishu County finance minister Julius Rutto is currently filing an appeal to the Ministry of Health because his county budget was deducted Kshs 200 million during the 2018/2019 budget, but, Rutto told AU, the value his county has received in equipment is “less than ninety million shillings”.

Timeline of events.

Coercive vendors

In an interview with AU, one former regional health minister who had been serving at the time the MES contracts were initiated and who asked to remain anonymous blamed “coercive vendors,” i.e. companies who supply goods to the government: “We learnt sadly that you easily get run over if you stand in the way of coercive vendors in Kenya,” he said, adding that “budget development (in the Kenyan state) in general, is largely vendor-driven; and the objective types among us do not survive long enough in the policy space to effect sustainable change.”

Recent Cabinet reshuffles have complicated our quest for answers from central government. The Health Cabinet Secretary whose responsibility was to sign the contracts (but who apparently did not do so) is now the Cabinet Secretary for Transport, Infrastructure, Housing and Urban Development; the Principal Secretary for Health is now assigned to the Lands Ministry and the later Cabinet Secretary for Health, who was in charge of the contracts after 2015, is now Kenya’s Ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva.

In general, besides the response received from the Ministry of Health on our request to see the contracts, no responses were received on numerous requests for comment directed at government by phone, in written emails and hand-delivered physical letters.

*IFMIS – Integrated Financial Management System

- Figures from 2012 in the 2014 Kenyan Ministry of Health’s Human Resources Strategy Plan

- Thanks to the attention given to the case of Esther Wambui by Africa Uncensored in Nairobi, well-wishers have organized funds to help pay for her cancer treatment.

Joy Kirigia is a broadcast journalist, currently working with Africa Uncensored, an independent media house based in Nairobi. She is passionate about human-interest stories, with a key interest in matters health, education and governance. She has produced a series of reports on health, education and data related stories and has been actively practising journalism since 2016.