When British mining outfit Gemfields Group Ltd launched a local partnership in Northern Mozambique, hopes were high that the taxes earned from this new company’s operations would help a historically disadvantaged region to develop. Several years down the road, amid a series of broken promises, hope is waning. But what went wrong? How millions of dollars don’t end the misery on the ruby fields.

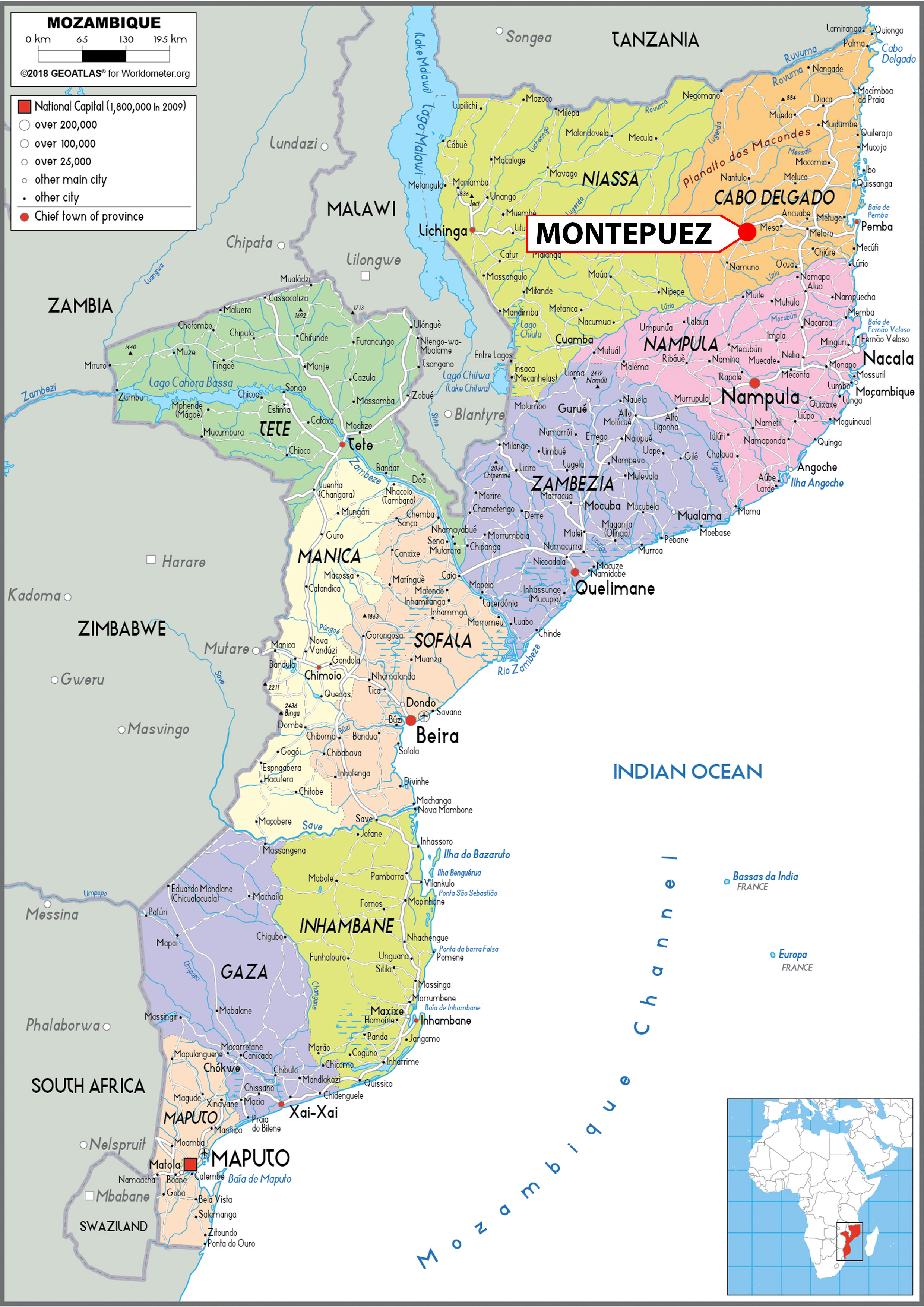

"We could say that there was an error," says Vicente Chicote, the police commissioner of Mozambique’s northern Cabo Delgado province. "When people don't have land, they have nothing to do; they live off donations and that's not enough. Some of these people get involved in illegal mining activities". Earlier in our interview he has described the artisanal miners of the province’s Montepuez district as "violent" in their confrontations with the police, explaining that they "throw stones and pickaxes". The confrontations are worsening because of the local loss of land, which was caused by the government’s decision to grant a large area of the region as a concession to a company called Montepuez Ruby Mining Ltd (MRM).

But my question had not been about illegal miners, violent or not. I had asked whether Chicote worries that the artisanal miners and the other uprooted people of Montepuez, who were forcibly removed from their lands and forest mining sites when commercial ruby mining took off over ten years ago, might join the devastating insurgency that has plagued the province for years now. Many assessments, from sources as diverse as the European Union and Mozambique’s former First Lady, acknowledge extreme social inequality and rapacious resource exploitation as root causes. The criminalisation of artisanal miners has also led to fears that they might end up rubbing shoulders with others on the wrong side of the law.

Montepuez administrator Isaura Maquina says her authority does "everything (it) can to prevent the youth from going to terrorism or illegal mining activities," then adds immediately that "it is also a question of behaviour. Many of the local children just work on the land with their families." But for that to happen you have to have land. And ever since large parts of rural Montepuez were cleared to make way for ruby mining, hundreds of families have been forced off their farms and out of the forests where they had foraged or, more often, individually looked for rubies. The crude violence committed by security forces in this process meant that families were traumatised as well as dispossessed. (see box ‘Scaring away the monkeys’). In a comment, MRM states that villages themselves have for the most been left intact.

MRM is 75% owned by UK multinational Gemfields Ltd, while ruling Frelimo party top member and retired Mozambican Army general Raimundo Pachinuapa owns the remaining 25%. Partnerships with Frelimo ruling party supremos are the rule, rather than the exception, in the conflict-ridden Cabo Delgado province. Practically all international mining companies that have been allocated mining licenses here count ruling party leaders, security chiefs, mayors and politicians among their shareholders and directors.

I am not saying if it was fair or not. It was legal.

Officially, the uprooted families were supposed to be given other land, as well as means to engage either in artisanal mining, or a profession, or a small business. There was certainly enough money to provide for such alternatives. MRM and its British-based parent company transfer 10% of their ruby auction revenues to Mozambique annually, of which 2.75% is paid directly to the Montepuez district authorities. In 2021 alone this amounted to close to US$250,000 earmarked for the creation of economic opportunities in an area of 300,000 inhabitants. (In 2018, before COVID disrupted the industry and the global economy, this contribution has been close to US$1 million.) This revenue is in addition to the regular annual corporation tax of 32% which the company pays to the Mozambican government.

The tax revenue is the main reason why both police commissioner Chicote and district administrator Maquina feel they must protect the mining operation at all costs. "We need law and order, because this is tax money for the benefit of the country", says Chicote. Maquina gets upset when asked about the desperation brought by the mine. "We work very well with the mine! They pay tax!" she insists.

Landlords with machetes

It's just that Montepuez has so little to show for all that tax. Asked when and where landless farmers can now farm again, Maquina admits that "some farmers don’t have their fields yet." I ask about Ntoro village, where families had been directed to go cultivate land in a certain area only to be "met with landlords with machetes who were already there", as per local complaints, she talks of an “impasse […] (But) we did follow the law", she adds. “I'm not saying that the resettlement was fair or not […] but it was legal." The district’s allocation of artisanal ruby mining opportunities to local mining associations has stalled, too, and Maquina also admits to that. "Spaces were concessioned to the associations", she says. "But the problem is lack of resources for tools." She emphasises that the communities have "the support of the government in the legalisation of the space." But even that is doubtful: several local miners recently complained that they found their "legalised space" suddenly reclaimed by mining companies again.

The ‘clinics’ are vehicles

Asked what the district does to assist displaced communities, Maquina mentions a number of water boreholes, the electrification of one village, some schools "under rehabilitation", and the procurement and management of several "mobile clinics". Closer scrutiny, however, reveals that a mobile clinic – just one, not several- and four schools were actually funded directly by the mining company as part of a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programme unrelated to their tax obligations. I found only one school, comprising three classrooms, that could have been built by the provincial government.

With regard to the clinic, locals report that this is simply a vehicle that drives past villages once or twice a week to collect those who are sick and to take them to nearby clinics, which in turn also often suffer from lack of drugs and equipment. According to the Gemfields mining company website, the Mozambican authorities have pledged to provide health workers to staff the clinic vehicle and provide medicines to supply them, but there has been no sign of this so far.

Poorer than they were

In 2016 a class action lawsuit on behalf of victims human rights violations in the ruby fields was brought against Gemfields, Mozambique Ruby Mines Ltd’s British parent company, at the High Court in London after UK law firm Leigh Day approached community activists in Montepuez. The suit was settled when Gemfields agreed to pay £5.8 million to the claimants on a no-admission-of-liability basis. This sum included Leigh Day’s expenses.

Sadly, the money did not improve many lives in Montepuez. Since the recipients did not have experience in handling such large sums, "many became poorer than they were", says Rachid* from Nacole village. "Some bought motorcycles, others even minibuses (to start taxi and transport businesses) but they never made it. Others married three women, had more children, in the case of others the money ended up in bars. They were partying, drunk, others walked with two hundred thousand meticais in their pocket, they abused and provoked people, showing off their big money and of course ended up taking a beating."

Moma actually did well, he says. "I managed to buy a truck, bought appliances and a grain mill, I managed to build a house." So did João*, also from Nacole. "I managed to change my life," he says. "I bought two cars, built two buildings, built my house right there in my community. The rest of the money I invested in small businesses." However, he and others soon found themselves accused of terrorism. "Mr Horacio, and Mr Sumail, from SISE (the State Information and Security Services) authorised raids on our houses, because they said "you have that money from Al Shabaab”. They confiscated goods TV’s and motorbikes and shouted that they wanted a list with names of everyone who received money and how much. They even took me to court, but thank God I'm fine."

Beneficiary Abdul Jaime says he was so terrified after being summoned to the prosecutor’s office that he ran away from his house, only to find that the police came to search it while he was away. "I had to go to the police station to show them all the documents about the compensation," he says. "But they only released me after I paid them a thousand meticais (US$15)."

*Names changed upon request

Empty markets

"You built two markets in Nanhupo", says Andre Carlos at a meeting between community members and district officials in the area. "But we cannot use them because they are in the bush, far outside the village." The example illustrates a pattern of wasteful projects that pay high sums to contractors, but are of no use to the locals for whom they were meant. "At the time of planning, we are invited to present projects that we need", another villager adds. "But we never get what we ask for. Sometimes we bring a budget for a specific project, and then you (the district authorities) suddenly have a budget of even greater monetary value, but it is for something else." A third one summarises: "The district does what it wants, that's the problem."

The district representatives nod and take notes. They don’t respond.

MRM is aware that “its taxes do not always benefit local communities

In a comment, MRM Gemfields says it would "welcome more of its tax contribution being deployed within Cabo Delgado and in the communities surrounding MRM" but that it is "presently unable to obtain an account of how its tax contributions are deployed by government." It adds that "MRM is aware that its taxes do not always benefit the local communities and hence undertakes additional local projects in order to address this."

Caught and jailed

And so many locals continue to try to make a living from the forest, as they had done for generations before the mining concession came along. Unfortunately now they get prosecuted as a result. "We depend on that forest to help our families," says Constancio Jaime, an inhabitant of Namanhumbir, the main town bordering the ruby fields. "But when we go there to look for resources, even wood or bamboo, the government will accuse us of stealing."

In 2018, Jaime’s neighbour Antonio Maremula spent three months in jail in Mocimboa da Praia district, just before the area was overrun by the insurgents from Al-Sunna wa Jama'a, often referred to as the "local Al Shabaab" (after another Islamist group, from southern Somalia). "Fortunately my family managed to send money for transport, so when they released me I got a bus to travel back to Namanhumbir." Two years later Maremula was caught again, this time in Nseue, where he was convicted again. The third time, he stayed in Montepuez police station for two weeks. "My family paid ten thousand Meticals (about US$150) in bail." Omar Eugenio, from the same area, had to pay thirty-five thousand Meticals (over US$ 500) to get out. "My family had to sell my house in Namanhumbir and another relative also had to sell whatever he had in his house."

It’s either to starve or to choose banditry

Scaring away the monkeys’

"Our job was to ‘scare away the monkeys’, which meant not letting illegal miners into the mine," says Selemane Hassane. "They called them monkeys because whenever we chased them away, they came back." Hassane is a former nacatana (literally ‘machete’, or security guard) and a member of a group of three hundred ex-MRM employees in Montepuez. The local security men among them have recently started talking about their work during the early years of mining between 2011 and 2014, when the ruby fields were first cleared.

Augusto Faustino, a colleague of Hassane at the time, says he was ordered to tie up captured artisanal miners with ropes around their necks, and that, when he refused, he was told that "if I did not torture the Mozambicans I should leave the company". Other workers talk of being forced to tie people to trees and beating them, of shootings in full view of the state police "who did nothing" and of incidents where "arrested" individuals were humiliated, including accusations of serious sexual assault.

MRM Gemfields says in a comment that it "takes allegations of this nature very seriously" and that it would "appreciate it if the individuals could provide further information so that it can investigate the claims fully and with due process." The group of ex-employees has been asking MRM for back pay on their salaries, but for now there is no end in sight to that process.

The miners say they are also still attacked and extorted by the elite Força de Intervenção Rápida (FIR) police force and the Fauna and Forest unit, who confiscate their hauls of camada, the sand that contains rubies. Last year three people were again shot in the concession, says Luis Florentino, who is also from Namanhumbir. "They broke their legs, one lost his life. We saw an ambulance today again, on its way to Pemba. It doesn't end. These are sharks." "But we have no option", says Constancio Jaime, also from the village. "It’s either to starve or to choose banditry."

A recent report by CIPMOZ, the Mozambican Centre for Public Integrity (5), lambasts the way both the Montepuez authorities and the national government handle mining revenue in the country. It points out that investments from this revenue in poor areas remain largely "invisible". With regard to the 2,75 % tax that is paid directly to mining districts, it states that the district governments hardly ever know the amounts this translates to, and that they take decisions on expenditure "without consultation or transparency", which risks funds being siphoned off or wasted. CIPMOZ also warns that unexplained expenditure in one area and not in another also "has a strong potential to generate conflict." It recommends more transparency, independent oversight and a channel for national mineral revenue to benefit the provinces.

Maputo-based economist João Mosca agrees to the need for transparent financial investment lines that fund services such as water, health, and education, but feels that communities should also be empowered to monitor such projects. Democratic organisation is needed for this, he emphasises. "There are now diverse interests (that can cause conflict) between traditional leaders, local state leaders, and different families. It’s only when communities organise themselves that they can make demands of the state."

For now, however, the only well-organised force in Cabo Delgado is the ruling party, Frelimo, whose wealthy elite is, in the words of José Jaime Macuana, a political sciences lecturer at Maputo University, "strategically allied with capital and large investors." "Mozambican citizens are left behind while the oligarchs are on the side of companies", he says. "It is not that there should not be investments, but when people are aware that there are exploited resources that they do not have access to, this can be a trigger for instability and revolt."

Meanwhile the Islamist insurgency in the region is also a growing concern. Locals are scared of being caught up in it- they’ve heard enough stories about beheadings, rapes and massacres, not least from the thousands of families in nearby IDP camps. But the beheading of two people at a farm house outside Muaja village, about thirty kilometres from the MRM mining concession, on 13 July, shows that the threat is coming nearer. Special troops have since been deployed to protect the mining area.

A recent report by the Global Foundation against Transnational Organised Crime, which refers to the terrorism risk, recommends a number of measures that the Mozambican government should take in order to protect disaffected young men impoverished by the conflict between the mines and the population from being vulnerable to recruitment by insurgent forces. It suggests that the state should tackle corruption, professionalise its law enforcement, work improve the trust between the state and local populations, and "invest in the region to address economic inequality." For now, however, Mozambique’s President Nyusi, along with his government and security chiefs, staunchly maintain that all terrorism comes from "abroad" and that "poverty" is not causing locals to take up arms. The Mozambican parliament recently approved a law making it an offence to spread “disinformation" about terrorism.

Estacio Valoi was a runner up for the African continental FAIR award in 2012 for his work in uncovering government corruption in illegal logging. He also won the Environmental Journalism Award from the Worldwide Fund for Nature in 2017. His work has been featured by Le Monde, Mail & Guardian, Foreign Policy, Al-Jazeera, Daily Maverick, The Star, Deutsche Welle and CNN, among others.