When COVID 19 hit Mali, businessman Boubacar Thiam was one of the many who felt a ‘sense of panic’. ‘Maybe I should have thought about it for longer’, the chairman of APBEF, the association of financial and banking enterprises of Mali, says. ‘But we were told there was a global pandemic and many of us might die. So we put US$ 1,234,885 into the voluntary fund that the government presented. We did not foresee that there would be no traceability’.

On a picture taken at the 1st of April 2020 launch of the Mali Voluntary Fund For the Fight Against COVID 19, dignitaries proudly pose with representatives of business, civil society organisations and other prominent individuals, holding a placard symbolising a cheque of close to US$ 7 million. Malians were to fight COVID together. Prime Minister Boubou Cissé took personal charge of it.

Four-and-a-bit months later, the fund seemed forgotten. There had been a coup d’état in August. The government had left its seat. Nobody seemed to know anything about the fate of the fund. No report was offered; those who had donated were kept in the dark. Boubou Cissé kept mum: he was busy with a new election campaign, on which he was seen to be spending quite a bit of money.

It would take until the end of March this year, 2021, after questions were raised by those who had contributed – and also, separately, ZAM had started to investigate – before it was heard of again: now as the subject of an ‘enquiry’ by a ‘study group’ in the Ministry of Finance into why, at least on paper, none of it had been formally spent.1

It was not like there had been no need for the money. COVID 19 had been real in Mali throughout 2020. The state had even prepared a whole ‘Plan of Response’ to the pandemic, with an overall budget, amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars, that dwarfed the voluntary fund. The ‘bigger’ money, to be secured from development partners like the EU, the IMF and the World Bank, was partly to be spent on medical needs and partly on relief for citizens. Food was to be procured centrally for distribution among poor communities where people could not go to work because of the pandemic. On the part of the Treasury, water and electricity was to be subsidised so that people could be offered a stop on their bill payments. On the medical side, the plan allocated ventilators, medication, sanitiser, and danger allowances for medical personnel and, most importantly, in a country where the word ‘hospital’ often means ‘a set of suffocatingly hot and overcrowded rooms with not much help for patients to begin with’, a project to ‘uplift the technical levels’ of the health centres.

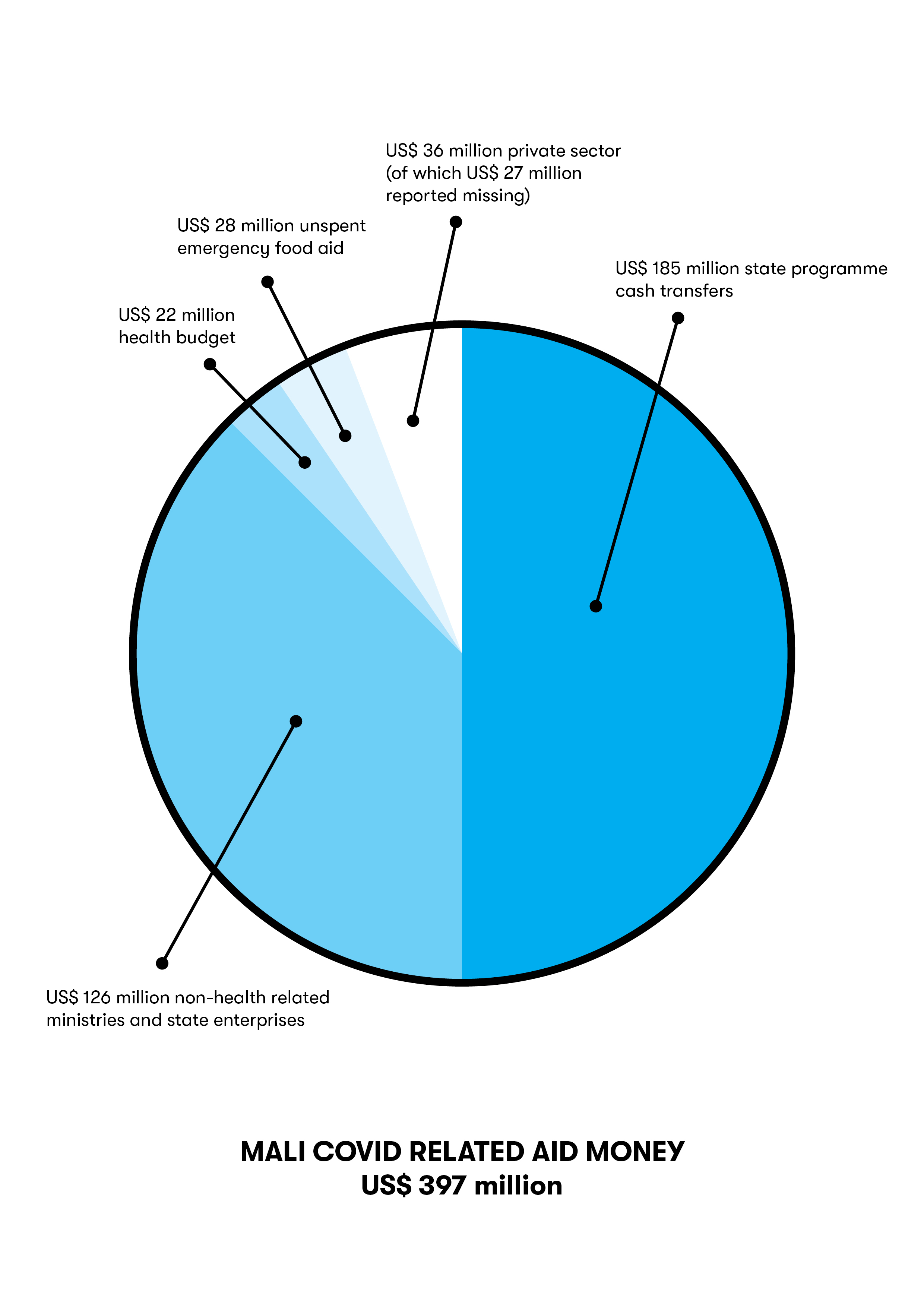

The development partners paid. An expense budget for the Plan of Response to COVID 19, later retrieved by the local NGO Publish what you Pay2, shows that the acquired relief funding altogether amounted to over US$ 397 million.

Remarkably, the initial voluntary fund had not been included in this budget. Finance Ministry spokesman Moustapha Doumbia would later explain that that is why his department had been unable ‘to touch the money’. Saying only that ‘it is a budgetary principle not to touch money that has not been budgeted for’, he did not explain why no one had done such budgeting, nor whether or on what it was going to be spent now.

The government firstly paid itself.

In contrast, the giant budget allocated by the development partners was nicely itemised.

The expenses in the report issued by Publish what you Pay show that, firstly, the government was quite upfront in immediately transferring US$ 162 million, over one third of the money, to bolster non-health-related ministries like Safety and Security, state enterprises like the water and electricity companies and, on paper at least, a reserve for the private sector including ‘certain affected large businesses’. The report also shows that US$ 28 million for emergency food aid would remain unspent at least until December 2020, when it was published. Until that date and possibly still afterwards the money would stay in another department of the state, the ‘Commissariat for Food Security’. Another US$ 185 million in grants support ‘for needy families’ was paid into the state’s Jigisemijiri programme, that supposedly organises cash transfers to such families. Neither Publish what you Pay nor ZAM would find any beneficiaries from such aid. The Jigisemijiri programme is known to be riddled with corruption and fraud (see ‘Safety Nets’ insert later on).

It would later transpire, from sources in the private sector quoted by media in Mali3, that even the private sector and the ‘certain affected large businesses’ were short changed: an amount of US$ 27 million, promised to the Chamber of Commerce, ‘got lost before reaching’ that destination, the sources were quoted as saying. ZAM could not independently verify this. It is a fact, however, that from the US$ 397 million in donor funding only US$ 22 million was paid towards the Health Department’s budget.

Posters and pamphlets

At the time of writing this, in May 2021, there are certainly plenty of posters, pamphlets, banners and workshops warning against COVID 19 in the capital Bamako: proof that many ministries spent money on such items. We cannot find any households that have received COVID 19 relief or even masks, though. It is possible that some discounts on water and electricity bills – it was for this purpose that the state’s water and electricity enterprises had received large budgets – were put in place, but the beneficiaries of these would have been located in the middle classes. (As Publish what you Pay wrote in its report on the expenditure, ‘in poor communities people are not connected to electricity or (tap) water’).

According to spot checks conducted by Publish what you Pay in two poor villages outside the capital, nothing was received there from the government in terms of either food, money, masks, sanitiser or soap, either. Some of the latter items were observed, but these had been distributed by the mining companies where some of the men in the village were working.

With regard to medical supplies and support for health workers, the head of the Bamako Medical Order medics’ association, Modimbo Doumbia, says that he knows of practically no cases where health workers received sufficient protective equipment or allowances, and that ‘two hundred doctors contracted COVID 19 and fifteen died.’ Publish what you Pay, speaking to a hundred health workers, reported that sixty-eight out of these confirmed that they had been given no support whatsoever: not in terms of equipment and protective clothing, or the allowance also provided in the COVID relief budget, crucial in a country where salaries are often late for months on end. (Publish what you Pay did not give details with regard to what the remaining thirty-two health workers had received, only distinguishing between those who had received ‘some support’ and those who had received nothing at all).

‘We work in tents in suffocating heat without protective clothing’.

A high-level health official from the conflict-ridden north4 of the country who recently left the area and who requested anonymity for fear of repercussions5, told ZAM that ‘no clinic in the (vast) region (had) sufficient staff during 2020, even when in the region’s capital Timbuktu COVID 19 ‘cases exploded’. He also said that test results were hard to come by since ‘all the laboratories are in Bamako’, a thousand kilometres to the south. He added that ‘reanimation materials’ like defibrillators, oxygen and airway suction equipment were ‘almost non-existent’ and that there was a ‘screaming shortage’ of protective equipment for doctors and nurses ‘who worked in tents in suffocating heat’, until ‘local donors and NGOs delivered’.

The official also said that in all the clinics in his region health workers had protested against the lack of material and their bad treatment.

Chloroquine tablets

In the capital Bamako, 40-year-old Alou Traoré, a just-recovering COVID 19 patient at the city’s Point G hospital, calls himself a ‘miraculous survivor’. ‘The rooms are so dilapidated and hot, I had no privacy since I arrived and it has been difficult to keep my morale, or maintain hope for survival’, he says. A roommate adds that he did not trust the medication of one chloroquine tablet per day per patient. ‘It has side effects’.6 A quick tour through the hospital shows that the passages are overcrowded and that there is no ventilation in most of the rooms, while this is heat stroke season. In some rooms, patients from families who can do so, have installed fans sent from their homes.

The food was like cattle feed’.

On the outside, Bamako’s other and relatively new Chinese-built large health facility, the Hôpital du Mali, looks better than Point G, but the patients’ stories are the same. ‘It was good to leave that COVID trap’, says musician Moussa Sylla, who spent a few weeks here when he had the disease. ‘The only medication we were given was two chloroquine tablets per day, and the food was like cattle feed, inedible’. Mali Hospital and Point G have been officially refocused to ‘exclusively deal with the corona virus’, – which caused Ivonne Sylla (no relation to Moussa), who came from Sikasso, two hundred kilometers away, trying to find diabetes treatment in the capital to be told to go away – but in the end the mood among the people waiting for tests in the passages is that one might be better off trying traditional household remedies like lemon, hibiscus flower and wild herbs at home.

Publish what you Pay’s report shows that, on paper at least, some aid was delivered on some of the capital-based hospitals’ doorsteps as well as at two other places in the south of the country. According to the bookkeeper of Bamako’s Point G hospital, this facility received one bottle of ultrasound gel. One urine test. One metal bowl. Fifteen mattresses. One hundred bed pans. The list counts about a hundred of such itemised entries, with among the most expensive being a printer and a fridge. Summing up the money spent on in total seven hospitals in Bamako, as well as in the western region around Fousseyni and the east at Sikasso, Publish What You Pay counts up to US$ 3,7 million in such goods. Whether this amount came from the government’s US$ 397 million expense budget is unclear, however, since the itemised list also mentions other, direct donors.

It was not clear how much each bedpan cost.

It is also unclear whether the cost of the items listed really amounted to US$ 3,7 million or whether contracts were padded in the usual way. The fact that not one item is listed with an item price rings alarm bells in this regard, since this allows for costing one bedpan for example, at a hundred US$. This is normally done so that politically connected middlemen can receive their share, a common practice in Mali.7

For the rest, the local authors of the Publish what you Pay report oscillate between professional fairness and politeness vis à vis the authorities. Several pages are spent on the great objectives of the government’s plan. A paragraph on page 22 says that the personnel of the hospital in Sikasso ‘benefitted from various allowances’, while the paragraph directly below details that ‘lack of motivation’ resulted from non-payment of these same allowances, as well as ‘lack of medication, lack of test processing equipment, lack of sanitiser and lack of protective clothing’. The report also mentions at various instances that there were ‘administrative limitations’ when following up on the budgets, and that ‘we could not have the full accounts’. The director of the NGO did not respond to requests for an interview.

When asked to comment, the Mali government’s ‘Plan of Response to COVID 19’ manager, Akory ag Iknane, rejects all criticism and staunchly maintains that ‘all materials were delivered where they should have been’. Asked about financial accounts he only responds that ‘we don’t manage money’.8

Donor silence

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Finance, being the entity that does manage money, simply doesn’t answer the phone. Neither the Minister himself nor any of his advisers respond to requests for comment. The non-response aligns with the cancellation, already in December 2020, of all meetings (and therefore of the need to issue meeting reports) of the special government ‘Defence Council to Coordinate the Battle against COVID 19’. The last Prime Minister, Moctar Ouane, has stated that an audit on the management of the COVID 19 aid funds will be conducted by the Office of the Auditor General, but Malians do not hold their breath: the audits always come after the money has been lost. Also, on 25 May 2021, Moctar Ouane was arrested by the military in yet another government change in Mali.9

Trying to get comment from IMF, EU and World Bank is unsuccessful. The IMF says no one is available for comment, and so does the EU. The World Bank initially promises to answer questions, then doesn’t, then refers to a person who is on holiday. After the person is back, the emailed questions still remain unanswered.

Questions put to the World Bank (no response was received)

How has the World Bank assisted Mali with regard to COVID 19?

How much money has been mobilised to do this? What precise structure of the Malian state has this money been paid to? Would it have been in the form of a loan or a donation?

Has the Government of Mali formally requested assistance from the World Bank as part of the anti-Covid 19 response?

To what activity should the contribution of the World Bank go specifically?

What impact has the World Bank's contribution had?

Does the World Bank have a mechanism that allows it to monitor the money made available to the government of Mali as part of the anti-Covid 19 response?

Are any World Bank actions expected with regard to the anti-Covid 19 response?

Electioneering

Boubou Cissé, the minister in charge of the initial voluntary COVID fund that a ‘study group’ in the Finance Ministry is now claiming to be busy tracing, has been seen electioneering, driving around in luxury cars, with speakers and pamphlets and followers who get sandwiches and allowances. Paid with what, Malians wonder, but Boubou Cissé still doesn’t want to talk about that.

Businessman Boubacar Thiam says he will never donate to a government initiative again. ‘It would have been better if we had invested in medical equipment directly for the sick’. His organisation, APBEF, has recently bought medical equipment worth US$ 55,252 for the Point G hospital, he says. The receipt of the delivery is confirmed by the hospital over the telephone.

In May 2021 in Bamako, under the banners and posters saying that Mali is ‘dealing with COVID 19,’ young men, come twilight, hang around at street corners. Debating everything, they now mutter that the government just made this big pandemic noise to get more aid money. The newspapers report an urgent press statement by COVID 19 Plan boss Akory Ag Iknane, saying ‘Mali needs more help’.

Notes

- See: Mali : FONDS-COVID: OÙ SONT PASSÉS LES MILLIARDS ?

- The Publish what you Pay report is in the possession of ZAM. It has not been made available on the Internet.

- See: Mali : Fonds Covid 19: 15 milliards disparaissent entre la Primature et la chambre de commerce.

- See: The Siren Call.

- Anonymity was granted because, according to author David Dembélé, the country’s secret services tend to monitor state functionaries, particularly in the north, and one might get fired if perceived to be critical.

- The roommate said he experienced digestive problems. Chloroquine is a cheap malaria tablet that can affect heart rhythm and is not advised for treatment of COVID 19 (see for more the website of the World Health Organisation, www.who.int).

- See: Mali—Money Like Water.

- This is a response well known to journalists in Mali. High level state officials, when interviewed, seldom admit to managing any actual money. See also the Mali chapter in this report.

- There were two coups in chronically unstable Mali during this investigation. The latest one, in May this year, was conducted by the army, which promised a clean-up of the corrupt state. However, there have been no signs of an improvement in governance so far.