Ana's journey from nothing to nowhere

On 18 April, for fear of creating hotbeds of COVID 19 contagion, a Mexico City judge ordered the release of migrants from sixty-five overcrowded immigration centres in the country. By the end of that month, with both the northern and southern border lines under lockdown, the Mexican National Migration Institute (INM) estimated that over twenty thousand migrants were now stranded around border lines; under the lockdown, even appointments to identify refugees are suspended. Among those now either living in makeshift camps or left to their own devices in the country are an estimated four thousand Africans.

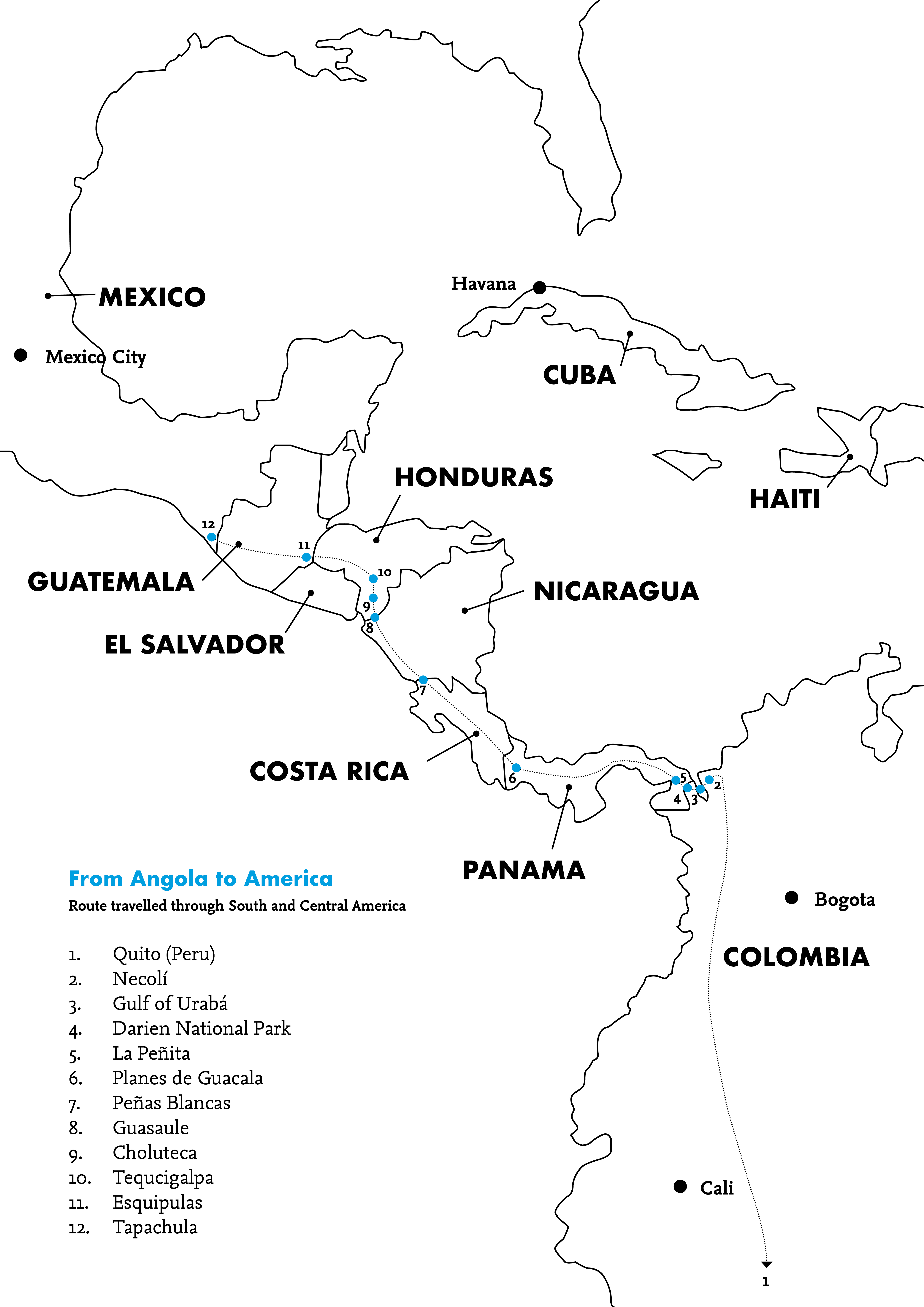

It was not yet like that, when Ana* arrived at in Mexico’s southern border town of Tapachula, in May 2019, but it was already bad enough.

A face from another universe

When I meet her in June that year her swollen face and dishevelled hair have long ceased to match the Ana from her WhatsApp profile photo. The smooth face, wavy hair extensions, outlined eyebrows, lipstick and big sunglasses; the golden necklace with a round green and white gemstone, all seem to have belonged to another time, another universe.

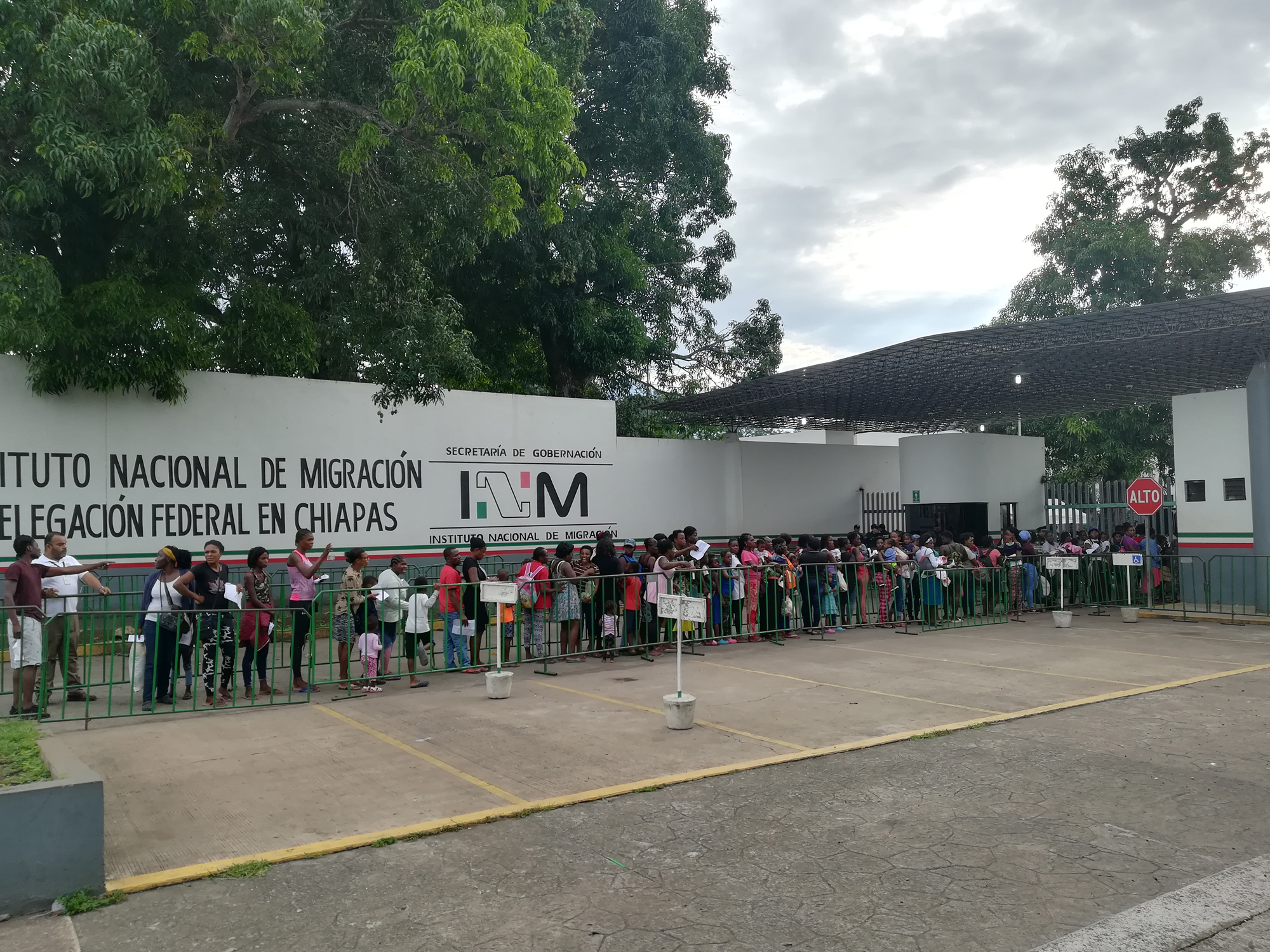

Ana, a 28-year-old Business Management graduate speaks three languages — Portuguese, English and French — but she could not find a job in her home country Angola. ‘I got tired of searching without finding anything’, she tells me. ‘I asked for a visa at the United States Embassy in Luanda, but they never responded. Some Angolan friends who live in America told me about this trip and I decided to take a risk. I went with my husband (who is from the Democratic Republic of Congo and French-speaking, PC) and daughter, Amélia*’. She and her family now spend their days in the sweltering heat around Tapachula’s Siglo XXI Migratory Station, the largest migrant centre in Latin America.

Tapachula is the almost-final wall to scale for migrants travelling to the United States. The official estimate of the number of travellers waiting here is one thousand, but there are probably close to four thousand here in this city, surrounded by humid jungle.

Ana has travelled around twenty seven thousand kilometres from Maquela do Zombo, Angola, to get here in search of a better life: a trip that involves crossing wild seas in rickety boats and weeks of walking through narco-gang territory in dense humid forest. Having risked rape, detentions and mistreatment along many parts of the way as well, it is still the forest that haunts most. Ana recalls ‘the days sliding in mud, the nights with poisonous insects, the fear of gangsters and snakes’, as well as ‘coming across graves of others’ on the way. ‘When I even mention the forest to Amélia (now eight years old, PC) she panics and starts crying’.

‘Angola is no longer for anyone, that's why I left’, says another migrant from Angola, who met up with Ana and her family along the way. João*, from Uíge, is 27 years old, with constantly darting, distant eyes in his small, frowning face. Like Ana, he lived in Luanda, with his wife and two children. ‘I worked at a store. They fired me overnight. I did odd jobs for a while but we could not live on that. I needed to support my family’.

Poverty without prospects

João and Ana are just two out of hundreds of Angolans who left Angola after 2014, when the oil price fell. Like Venezuela, Angola’s corrupt regime had relied on its abundant oil resources to keep the economy somewhat afloat. An ordinary Angolan could not get clean water or healthcare, but with oil money floating around most citizens could still grab a dollar here or there. However, when the oil wealth ended, while the elites had their billions safely stored off shore; many others faced a future in a broken country with no jobs and no hope.

Ana set out for the US with her Congolese husband and then seven-year-old Amélia, because that route, even if way longer, seemed more doable than trying to go via north Africa and the Mediterranean, where so many have been reported drowned. ‘We travelled to Namibia and took a plane to Quito, with a stopover in Amsterdam. That alone was six thousand dollars. And it was only the beginning’.

Brazil’s São Paulo is one of the first south American towns for many African migrants on their way to the US. Here, Angolans, like other Portuguese-speaking Africans, have a small advantage over others: thanks to a shared colonial history and Portuguese language, an Angolan passport can get you into Brazil legally.

Throughout our interviews, Ana keeps insisting that she is a legal migrant.

Raincoats and a flashlight

Once arrived in São Paulo you take a plane to Rio Branco, in Brazil’s extreme northwest, after which you cross through Peru. Quito, in Ecuador, is the hub. ‘We quickly found out how to move onward from other Africans, whom we met at a big square on the outskirts of the capital. We moved fast because every day you spend more money on food and a place to stay’, says Ana. Based on the advice they received they took an overnight bus from Quito to Colombia’s northern coastal cities of Turbo and Necoclí.

On web images the port of Turbo looks peaceful, with its mangroves, blue-and-white speedboats and fried fish market stalls. Daily, dozens of Africans pass here with camping backpacks on their backs, supporting the bustling street traders here with migrant dollars. Besides food, you buy a ‘travellers kit’ here: a plastic cover to protect cell phones and passports, plus a bigger one for around the back pack will set you back US$ 15. For US$ 20 more you obtain a special package that prepares you for the jungle: waterproof rubber boots, a flashlight and a plastic raincoat.

Perhaps the plastic, the boots and flashlight should have forewarned Ana and the others of what lay ahead. Firstly, like the Mediterranean, Turbo’s Gulf of Urabá in this part of the ‘Colombian Caribbean’ is starting to become a watery grave for unlucky travellers: just a year and a half ago twenty-three travellers drowned on the coast of Sapzurro, a few kilometres from the Panama border. Secondly, the jungle you reach after the water, besides being just as wet, is even more dangerous. But leaving from the idyllic-looking beach town of Necoclí, fifty kilometres north of Turbo, ‘where customs controls are less’ and Ana’s family paid US$ 50 per person for the boat trip to Capurganá on Colombia’s border with Panama , they had no idea what awaited on the other side. ‘These were legal boats’, says Ana. ‘The local people use them too’.

According to Colombia’s state migration agency, almost eight thousand migrants left from Turbo and Necoclí in the first four months of 2019 alone.

The trafficking of migrants through here is worth one million US$ per week

The forest of hell

The Darién forest, known to tourists as the Darién National Park, is referred to simply as ‘the forest’ by the migrants; alternatively also as ‘the nightmare’, or ‘hell’, as Ana calls it. Measuring 750,000 hectares in total, the jungle that clogs the border between Panama and Colombia is so impenetrable that the Pan-American Highway stops dead at its doorstep. ‘The path is completely closed by trees and plants’, João says.

It is only sixty-five kilometers to get through, but you have to place your fate in the hands of the traffickers, nicknamed coyotes, who know the way. In Colombia´s coastal Capurganá, where they are based, the crossing of migrants through Darién is worth about one million dollars a week. Working as a ‘coyote’ is so lucrative that, according to Father Aurelio Moncada, a local parish priest in Capurganá whom I interviewed telephonically, ‘young people and children stop going to school to enter the migration business’.

Ana and family, lucky to have had a mostly smooth boat ride, hoped to cross the forest in one or two days. ‘But it turned out to be many days of climbing up and sliding down hills under heavy rains, with your feet dragging through the mud, carrying your bags and food. And there are mosquitos. We heard stories of people who drowned here after the rains caused the river to rise. They had been sleeping on the banks and the water just took them away’. ‘Sometimes groups have to leave behind those who do not have the strength to endure’, adds João.

Other travellers mention noticing the clothes, food, bottles and toys left on the jungle’s zigzag tracks by migrants who either had to ditch their belongings, lost them, or simply perished, and the narcos of the Colombian Gulf who force you to carry drugs for them or else; other bandits simply rob you. Jacqueline*, a traveller from the DRC who made it to Tapachula, recounts how ‘bandits appeared out of nowhere’ when her group was resting to drink water. ‘They brought very large weapons. They put their fingers in the anuses of men and in the vaginas of women to see if we were hiding money. They threatened to kill us’.

A zinc hangar

Exiting the jungle in March 2019, Ana’s family was given ‘a little rice and beans’, in the village of Bajo Chiquito. They then took a twenty-five dollar canoe to travel four hours down the Chucunaque River to the only migrant station that Panama’s migration agency Senafront operates in the region: the so-called Temporary Humanitarian Assistance Station (ETAH) at La Peñita.

ETAH’s own photographs show the station as a zinc hangar, surrounded by metal fences and soiled blue portable toilets. Equipped to deal with a hundred migrants at a time, the place usually overcrowds with over a thousand, many of whom spill over into the village and sleep under trees. Its ‘humanitarian assistance’ consists mainly of registering and vaccinating the migrants against tetanus, measles and rubella, while Senafront takes fingerprints ‘to track possible criminals sought by Interpol’. ‘There were lots of kids with diarrhoea there, and sick people, but no medicines. There was only dirty water to drink’, says Ana. ‘Still, it was better than the jungle’.

After weeks, Senafront transferred Ana’s family, João and others, on a bus to the Planes de Guacala migrant hostel — a converted old hydroelectric installation — more than eight hundred kilometres to the north. ‘At that moment, the worst was over’, says Ana. Travellers commonly praise Costa Rica, as a place of kindness and officials who actively help them. ‘It was undoubtedly where they treated us the best, people are very kind and we never lacked food, support or medication’, João confirms.

The migrants quickly received passes to move on to Nicaragua, where, it was said, one could pay at the border to get further north to Honduras. In March 2019, Ana, her husband and daughter paid an official US$ 150 each in order to be shown to a low wall of about a meter and a half next to the border post. ‘It was very easy to jump’. Nicaraguan police officers were already waiting for their share of the bribe money on the other side. Boarding the mini buses to Honduras from there was another US$ 30.

The trip of 330 km, between Peñas Blancas and Guasaule, on the northwest border with Honduras, was also a smooth one, Ana and João say.

The heavy hands of Trump

It is in Honduras that one starts to feel the heavy hands of Trump. In early 2019, the US president threatened to cut over US$ six hundred million in economic aid to the ‘northern triangle’ countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras if these did not block the caravans of people walking on sore feet towards the United States. The result was much tightened immigration policies, both against own citizens who want to leave — Honduras, like El Salvador and Mexico, is tormented by poverty and violent gang rule (1) — and migrants from elsewhere. ‘Some go missing. Many are deported back, sometimes maimed and disabled (2)’, says Karla Rivas, the regional coordinator of the Mexico-based Jesuit Migrants Service in Central America, in a telephonic interview. ‘It is a very harsh reality of poverty and misery’.

Ana’s family and João passed through here a few months before the restrictions came into effect. They entered Honduras through a ‘blind spot’ on the border at Choluteca, then ‘walked through a small bush for an hour or two, then took a bus to (the capital) Tegucigalpa, where we obtained a pass to Guatemala’, says João.

It would become much more difficult for those who came later. In the last six months of 2019, Honduras’ Police Force for Migration Control stepped up surveillance of nineteen blind spots on the Nicaraguan border, Choluteca among them, arresting thousands. Early in 2020 the Honduran Migration Institute would boast that ‘illegal migration’ in the southern region had ‘decreased by sixty-two percent’ compared to the same period in 2019. The described success, however, only means that migrants now wander the border, waiting for a moment of distraction from la migra to continue the journey north. ‘We have a couple of thousand deported back to Honduras every now and then’, says Karla Rivas, ‘but also still hundreds leaving every day’.

Honduras meets Guatemala (and other neighbour El Salvador) in Esquipulas, home of the Black Christ: a wooden and very black statue of Jesus that is worshipped here by those displaced by war, the homeless and otherwise downtrodden. Joao and Ana’s family managed to get through here just in time in late March 2019: taking a bus, moving quickly, not visiting the Christ, spending US$ 30 on a single ticket per person. Ten months later, in January 2020, the country’s police, in a display of force never seen before, stopped a caravan of hundreds of Hondurans here.

Those in the know say that this was mere window dressing to please Trump; that Guatemala’s police is not really that capable; and that, like in Choluteca, arrested and released, or even deported, migrants soon get back here. But the new harsh rules require legal proof of residence in Guatemala for anyone wishing to buy a bus ticket. Migrants now fork out over US$ 100 for a spot in a coyote minibus or private vehicle to the country’s border with Mexico.

The migrants now cross at more dangerous points

Tecún Umán, the main crossing point on the Suchiate borderline river between Guatemala and Mexico, has also become quiet since the new security measures. ‘The migrants now pass through more dangerous points, in the north, that are more isolated and controlled by organised crime’, Mario Montes, coordinator of the NGO Casa Migrantes in Tecún Umán tells me telephonically. ‘Or they cross the river a little further south, where it is wider and deeper’.

Ana, her family and João crossed the river at Tecún Umán in May last year, still just before the clampdown, on wooden and rubber rafts. ‘They rocked a lot. We paid just over a dollar per person’, says Ana. On the Mexican side they found minibuses to Tapachula and forty minutes later they were here, where I would meet them two weeks later: tired, thin, and frustrated, but hoping to regularise their status at the Siglo XXI Migration Centre.

Then, on 30 May 2019, Donald Trump threatened to raise taxes on Mexican imports and within days from Ana’s family and João’s arrival twenty thousand National Guard soldiers marched in to create an anti-migrant buffer. A little more than a month later the Mexican National Institute of Migration (INM) abolished the procedure to obtain a pass to leave Mexico on the northern side, towards the US. The only way out now — it was still before ‘corona’ — was south, where you came from. But Ana and her family had spent over ten thousand dollars by then; they were not going back. “We started to contact our relatives in the US and Canada to send more money.” Canada, rather than the US, is where they hope finally to make a new life for themselves.

Memories of broken glass

Out of a total of over thirty thousand migrants in Tapachula, an estimated four thousand are Africans. Most hail from the Democratic Republic of Congo (a quarter) and Cameroon (almost half).

In early October 2019, the bodies of three Cameroonians were found floating off Puerto Arista beach, two hundred and forty kilometers northwest of Tapachula. They had each paid fifteen hundred dollars to coyotes to bypass Mexican National Coast Guard controls, but shipwrecked. Eight survivors (seven men and one woman) were detained, then given papers to stay in Mexico for a year; they have since disappeared without leaving any contact behind. There had been eighteen passengers in total on the boat, but no trace of the other seven passengers has been found to date.

You can’t go back to Cameroon, the West African country where a large majority of citizens starve under the kleptocrat regime of octogenarian autocrat Paul Biya and where the military violently oppresses dissent. In a mosquito-infested waiting room at the Tapachula Health Center, Favour*, who coughs incessantly, shows photos from her phone: houses with broken glass, burned buildings (‘this was the hospital’), shrapnel, soldiers, bloody bodies and corpses. This is the home town, Buea, in Cameroon’s south west, that she left behind four months ago, she says. ‘The military burned my parents’ and grandparents' house with them inside. Then they arrived at my pedicure salon and forced me to see how my sisters were raped. Then it was my turn. I was four months pregnant’. She starts to cry. ‘That day they also took my 17-year-old son, I have known nothing about him since’.

‘They can come from Mars, but we will send them back’, said the Commissioner of Migration

Of all those stuck in Tapachula, many of the men do odd jobs on farms and in construction; for women, the main way to get money is sex work. Local trade benefits from the foreigners’ purchases of cell phones, food and clothes, with whatever dollars they have left. Tapachulans also gain from commissions they charge for helping the migrants receive money transfers from relatives.

Even so, the local right wing press has long campaigned against the foreigners, accusing them of bringing diseases, as well as of littering and violence. And Mexico’s government doesn’t want them either. In October last year, the INM’s National Commissioner, Francisco Garduño, thundered that ‘They can even come from Mars, but we will all send them to India, to Cameroon, to Africa!’

The commissioner’s simultaneous referring to African migrants as ‘black humans’, got him accused of racism. He later apologised, but met a storm of criticism again in April 2020, when a protest by migrants against abusive and unhealthy conditions in a detention centre at Tenosique resulted in a riot and a fire, and a Guatemalan migrant died of suffocation. Over a dozen of human rights organisations in Mexico then signed a petition demanding Garduño's removal. The petition has so far been ignored by the authorities, however, and Garduño remains in office.

During the period when I met Ana’s family and João in June 2019, they were still continuing to try to get papers allowing them to leave in the northern direction. But ‘they (the authorities) don’t even talk to us’, Ana told me at one of the occasions I saw her. She was sitting on the ground then, next to a group of women queueing in front of the centre under a hellish sun. A few Africans, Cubans and Haitians wandered around and under some trees, a group of six or seven Indian men listened to frantic Bollywood-style music. The arrival of some buses disrupted the boredom and we watched as they entered the Migratory Station grounds empty, and left full. ‘Central Americans being deported’, said João.

Dreaming of Tijuana

On another occasion we met two Cameroonians who were suddenly very happy: they wandered around waving bus tickets and papers, and explained that they had managed to obtain a departure pass to Tijuana, border town with the United States. They were about to take the ‘Estrellas del Sur’ bus that was to leave at 2 30 PM to embark on the three day trip. ‘We have family in the US and we are going to apply for asylum’, one said with a big smile. In the background a radio played ‘Hoja en Blanco’, a hit from the 90s. ‘And fly, fly / In other directions / Go and dream, dream / That the world is yours’, the song went, in Spanish. The Cameroonians probably didn’t know Spanish, but the text fitted like a glove.

They had been gone before we could talk of the dangers that would await up north. The United Nations estimate that in 2019 alone close to five hundred people died on the Mexican border with the USA. Over a hundred of these drowned while trying to cross the Río Bravo or Río Grande; the rest lost their lives under the scorching sun of the desert. And those are only the recorded deaths. An estimated seventy thousand people have simply disappeared while crossing Mexican border territory: remaining under the radar at best, kidnapped or killed by organised crime at worst. In 2010, in the so-called Massacre of San Fernando, in Tamaulipas, Los Zetas, a syndicate regarded as one of the most dangerous of the country's drug cartels, massacred seventy-two migrants who refused to join their ranks.

Those who survive the crossing but are caught by the US Border Patrol, are placed in detention centers. These have recently attracted much publicity for their appalling conditions, separations of children from their families, and children held in mesh cages. A wave of solidarity from empathetic Americans after the media reports has since resulted in many coming forward ‘who take in complete families of migrants, even without knowing them, just to help’, says Sara Sorto, a welfare worker at the Espacio Migrante in the border town of Tijuana, in a telephonic interview. The luckiest of migrants now benefit of such arrangements, allowed by American law, and wait ‘in controlled freedom’ until the day of their deportation hearing.

‘The National Guard focuses especially on those with black skin’

Meanwhile, thousands who are afraid of the desert, the narcos and US border control, wait in improvised camps at the various border towns in Mexico to apply for asylum. Others ‘live in cheap hotels or apartments which they almost never leave for fear of being arrested’, says Sara Sorto, adding that the National Guard in Tijuana focuses especially on ‘those with black skin’. ‘The military and migra agents go out at night in the centre or the beach area and arrest those who cannot prove they are legally in the country, -which at the moment goes for practically all migrants’. However, ‘without any strategy for what to do next’, they are often released a few days later, presumably after once more paying bribes.

The last time I saw Ana, she said that that night the family would sleep in a pension in the center of Tapachula since they had a bit of money sent by relatives. ‘When it runs out, we’ll sleep on the street’, she told me as we said goodnight. A mutual acquaintance would tell me later that she and her family finally did succeed in reaching Ciudad Acuña, on the border with Texas. He did not know if they managed to get into the US.

But I imagine her and her husband crossing the Rio Grande, with Amélia in their arms, on their way to Canada.

Update: Migrants in the pandemic

According to Mexico’s National Migration institute only just over a hundred migrants remained in its custody after the ‘COVID 19’ closure of the country’s immigration centres last April. Over three thousand people had been deported to Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras.

Under the rules of the lockdown, gatherings in public places like parks and squares are now forbidden in Tapachula. Hotels and restaurants are closed. Migrant rights NGOs say that, while those who still have money are still able to rent rooms, others sleep on the town’s deserted outskirts. They also say that many experience hunger. The few shelters that still exist are dangerously overcrowded.

The Suchiate border river has been fenced off completely and is guarded by soldiers with face masks. An estimated seventy people reside on the river banks on the Guatemalan side, waiting to be let in to that country again. All along the border, further up north, shelters run by NGOs have closed ‘to prevent contagion’; migrants now roam the border lines and sleep in makeshift camps. According to the NGOs around three thousand people have converged in the largest such camp, in Matamoros.

Even for those who have decided to go back south — presuming that Guatemala will let them back in — the trip won’t be easy. There have been attacks on migrants recently from locals who fear virus contagion: according to the UNHCR, a Returned Migrant Service Centre in Honduras has had to close ‘due to protests by the local population against the entry of these people into the country for fear of becoming infected’. Similar stories come from Mexico. ‘We have been asking the government for data on measures to protect migrants, both from the pandemic and from hostility’, says Irineo Mujica, director of the NGO Pueblos Sin Fronteras. ‘The authorities do not even answer us’.

- Mayhem caused by criminal groups such as the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18 have turned Honduras and El Salvador, into two of the most violent countries in the world. Forced recruitment of young people by these gangs is one of the main reasons for them to flee the country.

- Many get injured on the trip; stow-away transport on La Bestia, the freight train that traverses Mexico, in particular, has led to hundreds of cases of mutilation when people fell off the roof or had limbs crushed between cars.

*names changed

This report was published earlier this year in Angola’s Novo Journal.

Pedro Cardoso (1982) is a Luso-Angolan journalist. He worked as a reporter at the newspaper A Semana, in Praia, Cape Verde. In 2006, he returned to Angola, where he joined the magazine Economia & Mercado and worked as the subeditor of Novo Journal in Luanda. He collaborated on academic works at the University of Coimbra and the Catholic University of Angola on Angolan society and politics. He is currently on a tour of Latin America.