“Each one, teach one.”

A little hidden in the CO-OP space of Unseen, the annual photography event in Amsterdam, we find Christine Eyene. With a hugely impressive CV as a critic, curator and an art historian, she is currently based as a research fellow at the University of Central Lancashire and a doctoral student at Birkbeck, University of London. She is writing a thesis on South African photographer George Hallett. Eyene has curated international exhibitions as part of numerous biennials including Printemps de Septembre 2016 (Toulouse, France); EVA International 2016 (Limerick, Ireland); Format International Photography Festival 2015 (Nottingham, UK); Summer of Photography 2014 (Brussels, Belgium); 10th Dak’Art Biennial 2012 (Dakar, Senegal); 3rd Photoquai Biennial of World Images 2011 (Paris, France). This summer Eyene curated Resist! The 1960s Protests, Photography and Visual Legacy at Bozar in Brussels, Belgium. She is currently working on the upcoming 4th International Biennial of Casablanca, which will kick off on 27 October and runs until 2 December 2018. Wow!

At Unseen this September she represents YaPhoto, the Yaounde Photo Network.

Eyene once started out as a photographer herself and was taught the profession by George Hallett. But as time went on, she discerned that there were many photographers in Cameroon, but not many writing on photography. That’s when her writing and then curating practices took off. She was approached by Landry Mbassi to set up a new platform for photographers and lens-based artists in Cameroon. In 2016 Eyene and Mbassi launched YaPhoto in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon.

Western photographers often fly in, teach and leave with no tools for follow-up

Instead of Western photographers flying in to Cameroon, teaching and leaving without providing knowledge and tools for post-production, the collective uses the resources and skills of Cameroonian photographers. Eyene: “The idea of YaPhoto is to show what photographers are doing in and outside of Cameroon, and to provide a space for photographers to talk about their work. What are we creating as Cameroonians?” By being a collective, strengths are clustered. “Each one, teach one”, says Eyene. She deliberately only gives feedback on technique and aesthetics, but not on not what subjects the photographers should touch on. The core is to really support everyone, share opportunities and create space for them to talk about their work with each other. At Unseen, YaPhoto therefore consciously shoes to show different genres within the collective.

In a conversation with the Ivorian/Swiss Klaym collective, Eyene is asked what’s represented in Cameroonian photography and what’s not? “There is a photographic language that came with colonialism (1) and that is now being explored”, she says. One of the legacies of this colonial past is a lack of critical approach and documentary photo journalism. The political situation in the country – with the upcoming election Cameroon seems on the brink of a civil war - is not helping to change that. In Eyene’s view, photography has a responsibility to comment on societal issues and show reality. It is not being made easy by a ruler of 30 years who does not intend to make space for a new generation. Also, matters like gender and sexuality are not being explored in photography. These are topics difficult to address. “People are scared to address them”, says Eyene. Only one photographer of YaPhoto is doing classical documentary work.

Artists need to show an expensive ticket without a visa being guaranteed

Another great challenge is the inequality in the global art world, especially the difficulties artists from African countries face in obtaining visas to the rest of the world. A visa application often requires an expensive ticket to show in advance, without any guaranties that the visa application will be approved. This is also the reason why only Eyene made it to Unseen. It seems that if you don’t have the ‘right’ passport you will not make it to the international platforms of the arts. It makes these platforms so much poorer. This shocking infographic shows the value of a passport as far as mobility is concerned.

Another big issue Eyene addresses is the lack of female photographers. She wants to get more on board. This summer YaPhoto launched a call to Cameroonian women photographers in order to achieve this:

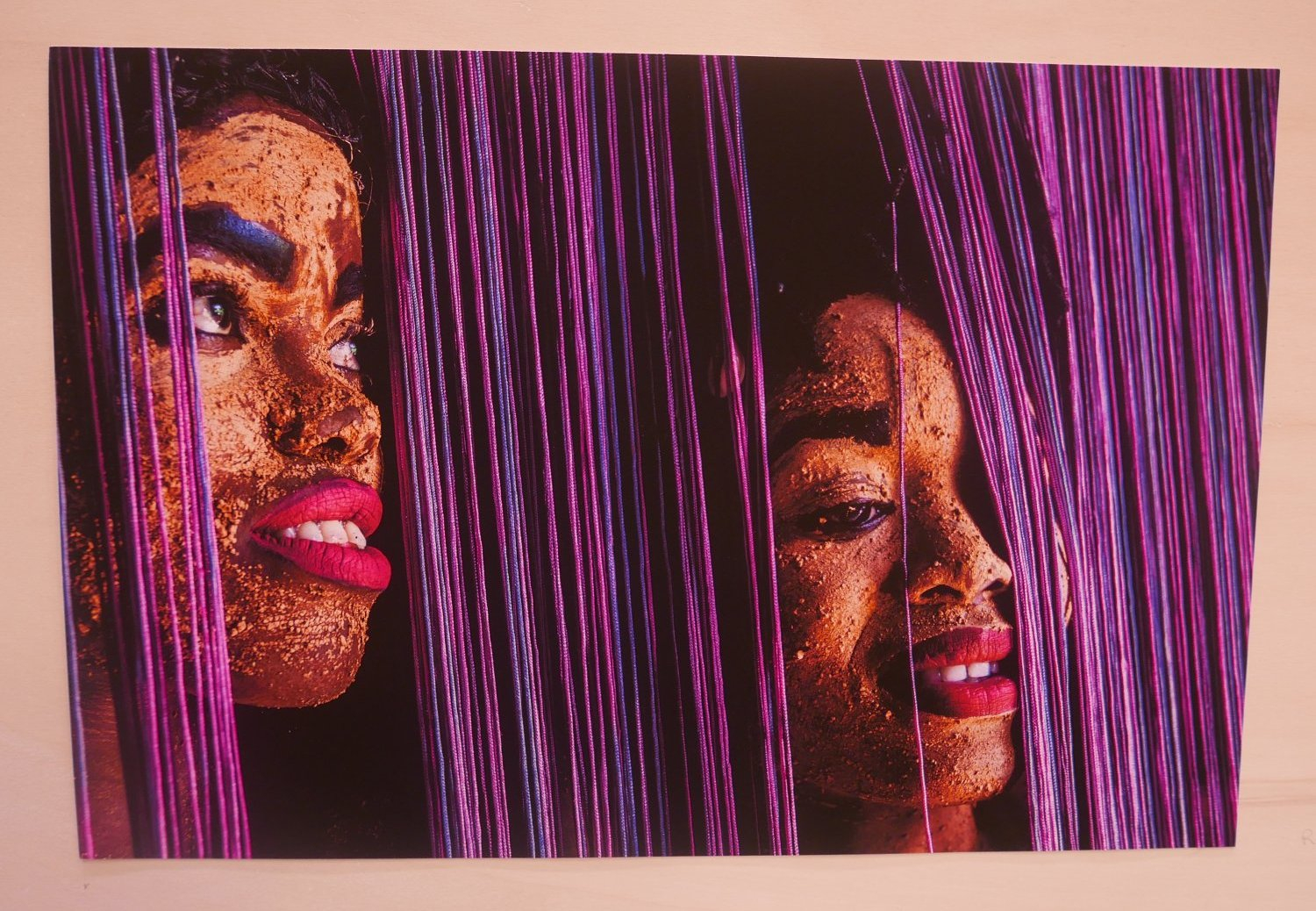

At Unseen, YaPhoto featured work by photographers Max Mbakop, Steve Mvondo, and Yvon Ngassam.

Check out all photographers of the network and their portfolios here.

- "The emergence of Cameroonian photography can be traced back to the early 1930s with studios such as the notable Photo George in Douala, which became a training ground for many first-generation Cameroonian photographers. Studios like Photo George, Photo Jacques (in Mbouda, Southwest Cameroon) and seminal figures like Nicolas Eyidi, to name but a few, have established the genres that continue to permeate the local photographic language, from the recording of important life events and privately commissioned portraits, to commercial and official journalistic or political assignments." Source: Eyene, Christine on viewbook.com/articles/on-images-yet-to-be-seen October 6, 2018.

Cameroon Press Photo Archive (CPPA-B) / Photographic Section was founded in 1954 by the British colonial administration. The mandate of the photographers of the Press Photo Agency was to follow any governmental or otherwise socially relevant events throughout its territory (today's Northwest and Southwest Regions). Colonial Film Unit (CFU) was another instrument that existed from 1939 to its formal disbandment in 1955. The CFU was originally established under the aegis of the Ministry of Information to produce ‘propaganda’ films, encouraging African support for the war effort. After the War, the CFU came under the direction of the Films Division of the Central Office of Information and, with funding through the Colonial Development and Welfare Act, now produced instructional films for African audiences. These films promoted community development and welfare programmes. Source: www.colonialfilm.org.uk