The ‘balanced’ movie about a ship hijacked by Somali pirates has been widely praised. But it’s Captain America all the way, with ant-sized Somalis and equally little context.

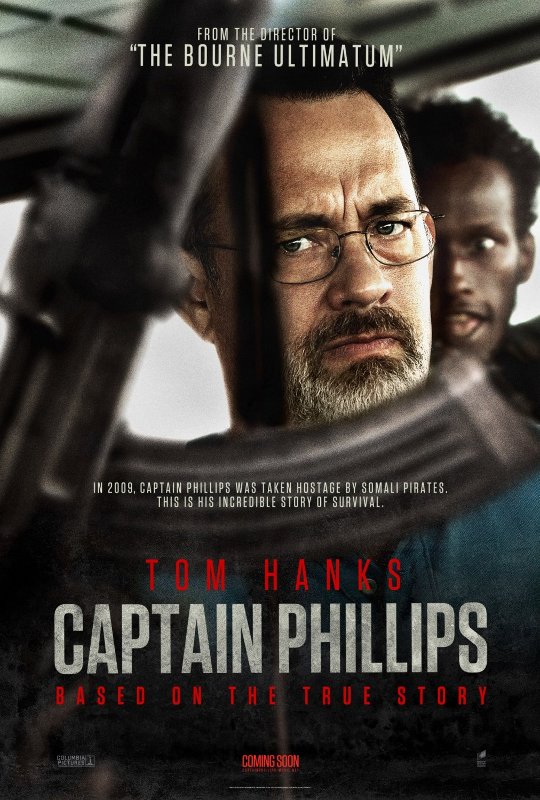

In the promotional poster for Captain Phillips currently pasted to the sides of bus stops, buildings and billboards, a stony-faced and steely-eyed Tom Hanks peers resolutely forward. With jaw clenched, lips pursed, and brow furrowed, his face is a study of robust determination.

The poster conveys most of what one needs to know about Captain Phillips, the new action-thriller/biopic that tells the story of the 2009 hijacking of the American cargo ship Maersk Alabama and the abduction of its captain, Richard Phillips, by a band of four Somali pirates. The narrative is bleak, the drama is hard-hitting, and the suspense is nail-biting. The film achieves all of those things because it exploits the most basic of motifs – the duality between good and evil – and makes it ignite on murky Eastern seas.

It is eye-catching, effective and successful because it keeps one thing crystal clear: the “good” man will always win.

A plain house with a picket fence

The story is, of course, told from the American angle. The “true story” on which the film is based is the memoir of Richard Phillips himself. He wrote the book upon his return to the United States in 2010 and titled it ‘A Captain’s Duty’. Sony Pictures bought the rights to the film shortly after the book’s release, and Paul Greengrass –of Bourne trilogy fame – was soon enlisted to direct.

Greengrass’ intelligent handling of the screenplay, together with brilliant performances by the film’s leading men, give depth and nuance to the narrative and open up some of the important questions that the script alone might have kept blocked. But even with an expert at the helm, this high seas adventure flick never truly beats the tide of Hollywood’s oldest formulae. Greengrass’ brisk and cutthroat directing quickly establishes the crucial dualities that are going to drive the conflict and we move through them with sure fire rapidity. The first frame is of a plain house with a picket fence under a mute grey sky in Underhill, Vermont. It is the all-American home base that has formed our everyday Joe of a hero. With a brief detour via the indoors, where we are introduced to Phillips as he assembles his papers for his call to duty, we are soon on the road to the airport with him and his wife.

It is here, in what is probably the film’s most uninspiring bit of dialogue, that Phillips lectures his wife on the dangerous direction in which the world is heading and voices his concerns for their two college-age sons. The unflinchingly grey skies ahead confirm the message: it’s a dangerous world out there, and we should be feeling as apprehensive as he is.

Danger boils under an oppressive sun

With Phillips’ general character traits established and the ominous tone set, we cut to the other side of the world, where we see danger boiling under an oppressive sun. This is the scene that is designed to introduce us to the soon-to-be aggressors and to the circumstances that underpin piracy. The smooth camerawork that guided us through the intro to Phillips is suddenly traded for the jerky style of a hand-held camera as we are made to move through the destitute Somali coastal town of Eyl. The shakiness of our vision is made to mirror the political instability that rocks the setting.

Abduwali Muse (played by Barkhad Abdi, and referred to as “Muse”) is introduced asleep under the roof of a corrugated iron hut. He, too, is enjoying a moment of solace before he is forcibly propelled into the terrible mess that inevitably awaits outside. The moment is short: vans full of angry men descend on the village’s khat-chewing populace, a young boy comes running to wake Muse, and before long, the young man is elected by a jarring chorus of shrieking voices to lead one of two boats out to sea on a money-making mission.

The basic parameters are now in place: two men, each a pawn in a much larger game, are bracing themselves to face their duty, and inevitably, each other. The asymmetry of the match is made patently obvious, and the film will soon emphasize its magnitude for dramatic and critical effect. But it is presented as just that: a complex state of affairs, whose sources are intangible, whose roots are too deep to dig, and in which culpability is so common that to search for powers behind it would be a waste of time. And as Greengrass’ fast-moving camera reminds us, we’re on a tight schedule here.

So in case our moral compass didn’t know where to sway, the terse-but-earnest Phillips, who we know for a fact loves his family (he’s been given the lines to say so) and has a white house in America to go back to, is probably a better bet than the scrawny, sleepy-eyed Muse, whose lips don’t speak a word over the bewildering cacophony he was born into. So much for those circumstances behind piracy.

Cat-and-mouse chase

The film’s following two acts are a harrowing cat-and-mouse chase on open seas. Greengrass sets up the hijacking through a suspenseful sequence that cuts back and forth between the massive Maersk Alabama, a mother of a vessel that glides slowly and steadily along vast open waters, and the rickety skiffs that crash their way across the waves with unmeasured zeal. The viewer’s sympathy is nudged further toward the American captain as he leads a lax and grumpy crew through a security drill. His no-nonsense philosophy turns him into a prophet as his fears are confirmed by the appearance of two miniscule dots on the ship’s radar.

The crew is soon given its fair share of sympathy as Greengrass establishes a contrast in the forms of fraternity reigning on the two boats. Whereas the Alabama’s crewmembers cast aside their differences with Phillips in the name of shared higher values – safety, loyalty, love of family and nation – the Somalis spit insults at one another while shrieking on about the millions they expect to earn from the hijacking.

The audience’s blood is pounding by the time the time that the four men are close enough to intercept the Alabama’s radio and to order, with cool irony, “Somali Coast Guard – routine check. Stop now.” The pace slows down and the soundtrack is silenced so that we can incredulously watch, through the lenses of Phillips’ binoculars, as the ant-sized Somalis board the colossal boat using a spindly makeshift ladder. Within seconds, shots are fired, and for some inexplicable reason, African drums begin to beat an infernal rhythm.

Face-off

The film becomes more mature and complex as the two leading men are finally brought to their face-off. Muse’s lines at last multiply once he is on the Alabama, and we can finally see his character thickening into a man of pragmatic conviction and tremendous cunning. He demands a ransom of ten million dollars from the ship’s insurance, and repeatedly asserts that no one will get hurt as long as the Americans don’t ‘play games’.

Abdi swells into the role, commanding respect through his level-headed confidence which is increasingly emphasized as his acolyte, Bilal, descends into a hyperbolical irrationality. With this contrast in place, Greengrass creates the room for a new brotherhood of sorts to form between the two captains, epitomized for instance in Muse’s sardonic adoption of the nickname ‘Irish’ for the beleaguered Phillips.

Of course, it’s just as the bonds of intercontinental / interracial brotherhood are being drawn that their star-crossed nature is revealed. Captain Phillips volunteers to be temporarily taken hostage by the pirates, and just as he’s staying one minute too long to give instructions to his crew members, he is knocked out and dragged onto a lifeboat along with the four pirates. The good Samaritan has been betrayed, and we know that time has thus come for dues to be paid.

The movie reaches its dramatic conclusion with the arrival of the technological and military might of the US Navy. In an unabashed display of pro-military pomp, parachutists swoop down on the pirates and two gigantic vessels imprison the ridiculously small orange lifeboat. With the Somalis’ desperation fully revealed and their impuissance made undeniable, Greengrass interjects some of the film’s most crucial exchanges between Muse and Phillips. There is an allusion to one of the most widely cited root causes of the piracy crisis: the illegal fishing carried out in Somali waters. In the screenplay’s most poignant piece of dialogue, a tragically resigned Muse reminds the self-righteous captain of the distance that separates their worlds.

Regrettably, these murmurs of critical perspective are swiftly siphoned into more moralising as the film again glorifies almighty America flexing its military muscles. Muse and his men are reduced to deer- in- headlights before the movie comes to its blood-soaked finale.

Fishing and warlords

Captain Phillips does have a lot going for it. Hanks and Abdi each turn in faultlessly strong performances as ordinary men stretched beyond the limits of intelligible human understanding. Moreover, Greengrass’ expert visual play with scale, angles, and perspectives does create the conditions for critical thinking. But more worrisome perhaps than the film itself is the press it has received. On this side of the Atlantic, where it premiered at the New York Film Festival and where it has been in theatres since early October, Captain Phillips has been hailed as one of this film season’s best tickets, not least for what critics are calling its earnest conscience, its respectfully balanced portrayal of events, and its incisive and conscientious ouvertures onto the absurd injustices of the global capitalist order.

Based on these reviews, it would seem that some vague allusions to fishing (four, in total) and a few references to Somali warlords are sufficient anchors these days for that elusive feature of Western movies that deal with global issues: context.

So yes – we probably should indeed be thankful that the movie isn’t more biased than it could have been. But how many more well-meaning works of pro-West propaganda do we really need? Aren’t we, in praising this movie, just as disingenuous as good old Captain Phillips himself, when he lectures his wife, earnestly but rather short-sightedly, on the dangers that lurk “out there” in the big bad world? What Captain Phillips lacks, in all its grim-faced moralizing, is an honest look into the links between the dangers out there and the many that come from within.

‘Captain Phillips’ (dir. Paul Greengrass, 134 minutes), is currently being shown in cinemas all over the world.

Lara Bourdin is ZAM Chronicle’s art editor.