There’s something happening in Algeria.

A spark of curiosity has been ignited and a community of photographers are emerging with different perspectives and questions on nationalism, tradition and the lived experiences of the people who exist within the country bordered by the Mediterranean Sea. Award-winning photographer, Abdo Shanan - who was born in the Algerian city of Oran to a Sudanese father and an Algerian mother, partially raised in Libya before later returning to Algeria in his twenties - is among the cohort of image-makers contributing to the visibility and celebration of Algerian life.

“I always felt that words were betraying me. There was a gap between what I could say and what was in my mind. I discovered that photography could be a mode of self expression.”

“I discovered that photography could be a mode of self expression.”

For us to fully acknowledge the importance of this movement, we have to journey back in time to understand the inextricable intersection of photography and politics in this particular place, north of the African continent.

In the 19th century, the formation of the second French colonial empire began, following France’s loss of a majority of overseas territory to the British, amongst other European superpowers in the century prior. The 1830s, a highly tumultuous era in our history, saw the French invasion and subsequent capture of Algiers, the capital and largest city in Algeria. In the same decade as this conquest, the first photograph taken on the continent was of the Ras el-Tin palace in Egypt, exposed on a daguerreotype by French painters Horace Vernet and Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet.

Across the region, private photographic studios specialising in Roman ruins began to appear - produced with an ulterior motive. It is these photographs that were used to justify the French conquest, due to a shared Latin history as both France and Algeria were once a part of the Roman Empire. By the 20th century, aerial photographs of cities such as Algiers and Oran were published in booklets and distributed across mainland France, with the sole purpose of spreading colonial propaganda. The power of photography’s influence on the state of a nation’s history and future are undeniable.

Now back in the present, we gain a broader glimpse into contemporary Algeria, through the lens of Abdo Shanan, as the country enters a different era of change and revolution. “Photography holds a complicated place in Algeria. People don’t always trust the camera so you have to be delicate, you have to build that circle of trust.”

Now back in the present, we gain a broader glimpse into contemporary Algeria, through the lens of Abdo Shanan

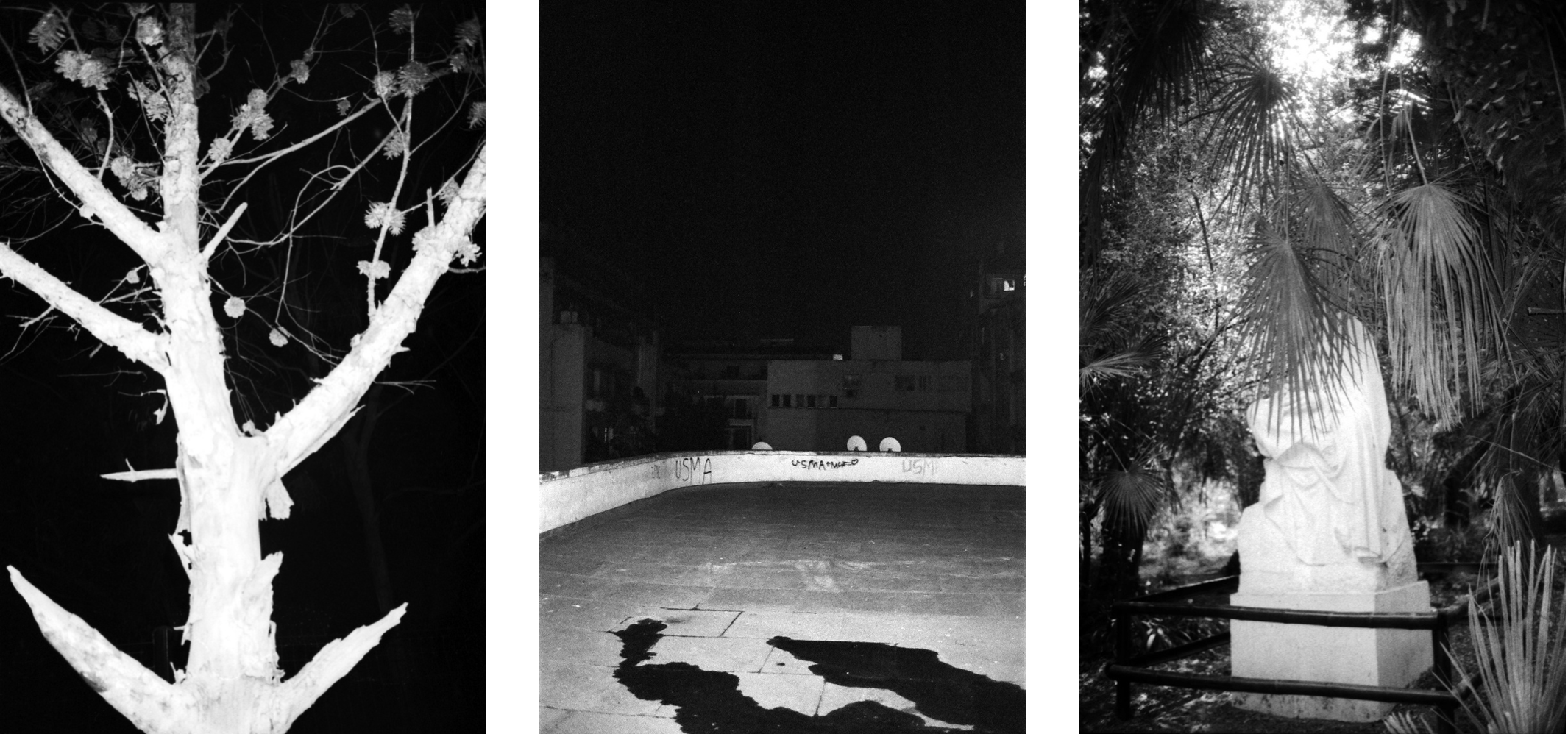

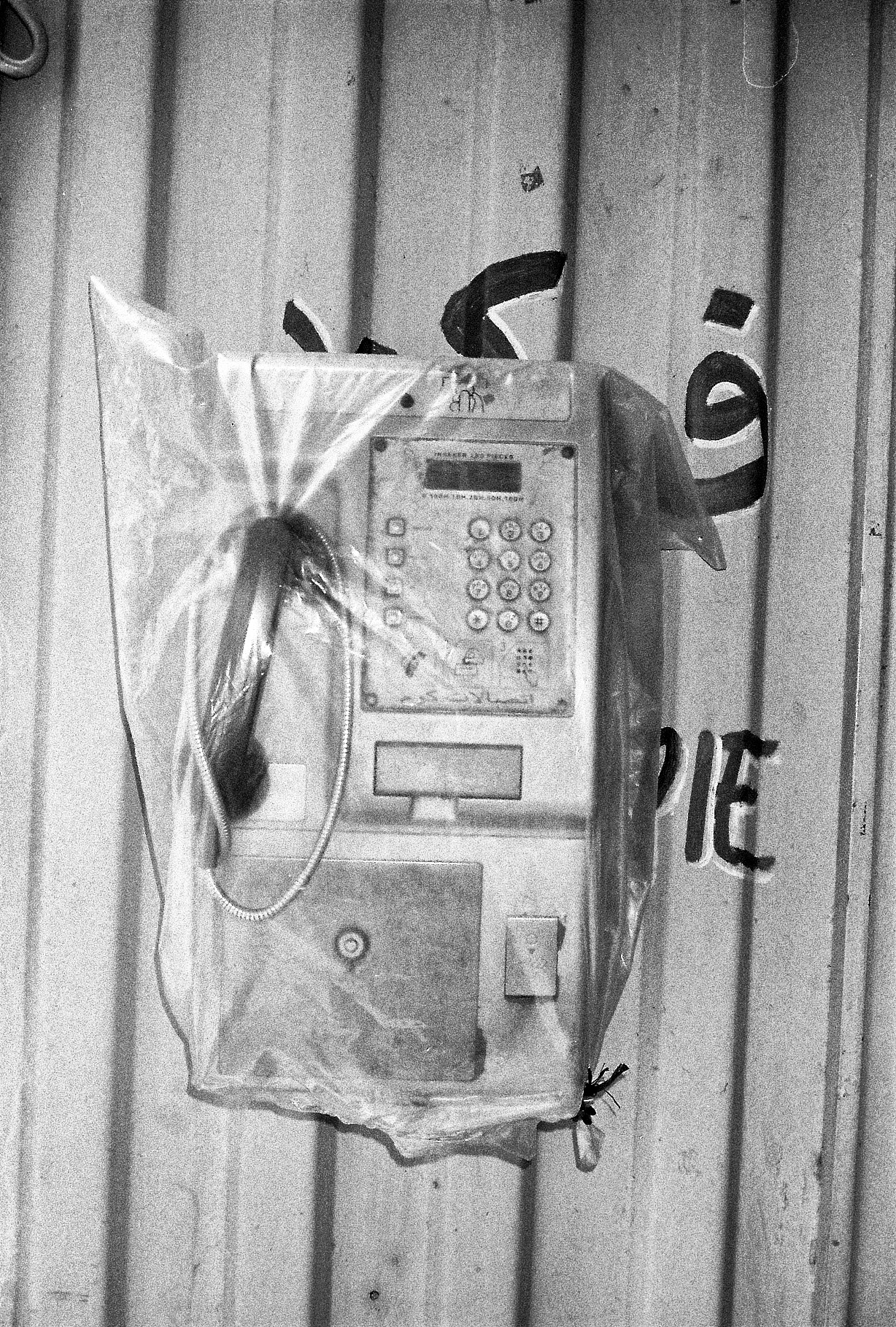

Shanan’s Dry, is a photographic project aimed at discussing the influence of the social environment on an individual’s identity - in a society that still bears the weight and trauma of a violent history.

“I remember someone once told me, ‘if you feel like you have obstacles in life, turn them into your own force.’” Revealing some insight into the process, Abdo shares his emotional state as he began to photograph, “At the time, I was a really angry person. I had this anger in me that I didn’t know how to let out. I feel like the use of tools like the flash was a way of letting it out.”

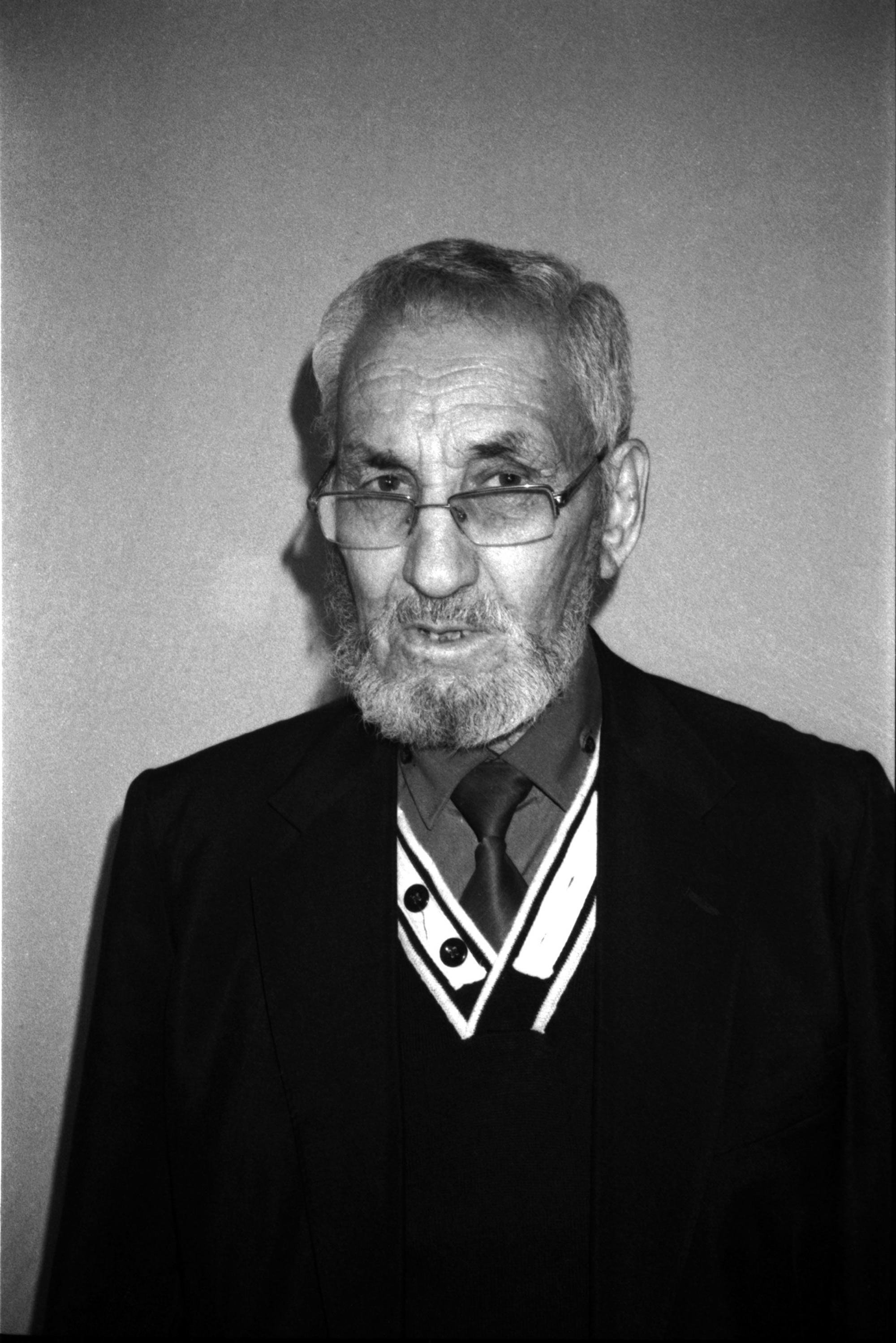

It is through this sort of channelling of emotions into the work that lead him to discovering his visual language and developing the way he works, “I’m not worried about what the perfect picture is. I need to gather elements in order to tell a story.” It is these components - consisting of unsettling landscapes, fractured objects, liminal spaces, a bent hand and a collection of quiet portraits, that create the whole. “I believe in the accumulative force of photography, when you put images together, you have a story.” Dry, which won the Contemporary African Photography Prize in 2019, allowed Shanan to understand the ground he was standing on in his home country. “The moment I became honest with myself, and became open to other parts of me, I realised this way of working.”

Abdo Shanan’s version of storytelling does not necessarily aim to get to a definite conclusion, but rather to be a catalyst, “I try to ask questions and hopefully it leads to new questions. I don’t think answers matter sometimes. What’s more interesting is the discussions around the questions.”

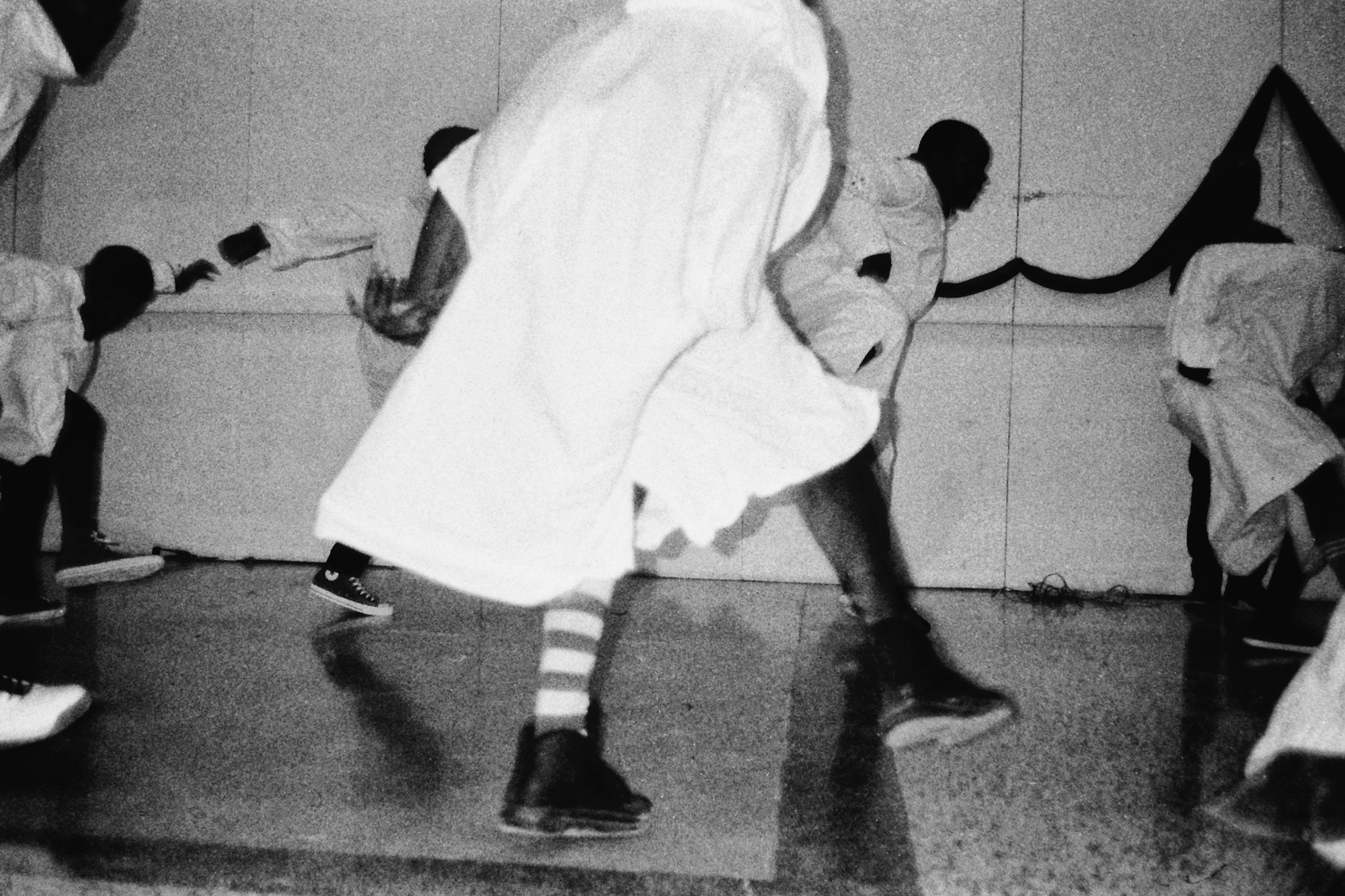

When curiosity occurs, it unfolds into itself and more becomes revealed. Exploring the layers, Abdo’s ongoing series Diary: Exile (2014-), feels like you are thrust into an uncanny realm of intimacies, veiled by his signature bright light that shrouds everything else in a kind of darkness. One cannot shake the feeling that they are in a dream, but it is in fact a vivid reality viewed from above and below.

“I’m not worried about what the perfect picture is. I need to gather elements in order to tell a story.” On 22nd of February 2019, the people of Algeria launched protest demonstrations in opposition of the candidacy of Abdelaziz Bouteflika to a fifth presidency mandate; these peaceful protests would later be known as the Hirak. Occurring every Friday, the world saw millions of Algerians take to the streets demanding change at all levels. “When the protests started, I was standing on the sidewalk looking at all these people gathered and I asked myself, ‘Do I want to be a photographer or do I want to be a citizen?’” He says profoundly,

“I’m not worried about what the perfect picture is. I need to gather elements in order to tell a story.”

“As I was photographing the masses, with little space behind and in front of me, I realised we all had a common goal but our motivation for being on the streets were not the same.” It is this understanding that led him to approach documenting the protests up-close, as a way of illustrating how in a protest of a million people, there are a million protests. By focusing on the individual, Shanan was able to capture the vehemence of the movement. “I photographed people the way I saw them…,” he pauses, “…felt them during the protests.”

“Some days you are comfortable, some days you struggle. It’s something I feel most photographers have to navigate.” Shanan’s process is fueled by a sense of persistence to uncover and discover, a momentum that cannot be sustained alone. It is through the support of initiatives such as the Arab Culture Fund, amongst other programs that the work can continue to be produced. It is also through being part of a community that questions can continue to be asked.

“Some days you are comfortable, some days you struggle. It’s something I feel most photographers have to navigate.”

In 2015, during a photography festival in Algiers, a group of photographers began conversations which resulted in the formation of Collective 220 - named after the room number in the Hotel Albert Premier, where some of them met. The collective now consists of seven members: Abdo Shanan, Celia Bougdal, Cléa Rekhou, Fethi Sahraoui, Houari Bouchenak, Soufian Chemcham and Youcef Krache. “We decided to start a collective in order to support each other as photographers,” he says, “When you come to the world as a group of people with certain beliefs, you are taken more seriously. It has helped us to be more present in Algeria but also outside of the country.” Together, these photographers are contributing to their country’s visual storytelling with projects such as Crossroads, a photography training program to develop young voices.

When considering the work of Abdo Shanan, and the generation of Algerian photographers he belongs to, the word that comes to mind is reclamation, not only of the photographic medium but also a claim of the country’s future. However, when much is given, much is required. “To be a photographer you have to sacrifice, it is not an easy job. But it is the kind of work that makes you who you are.”

This interview is republished from TOMBE magazine.