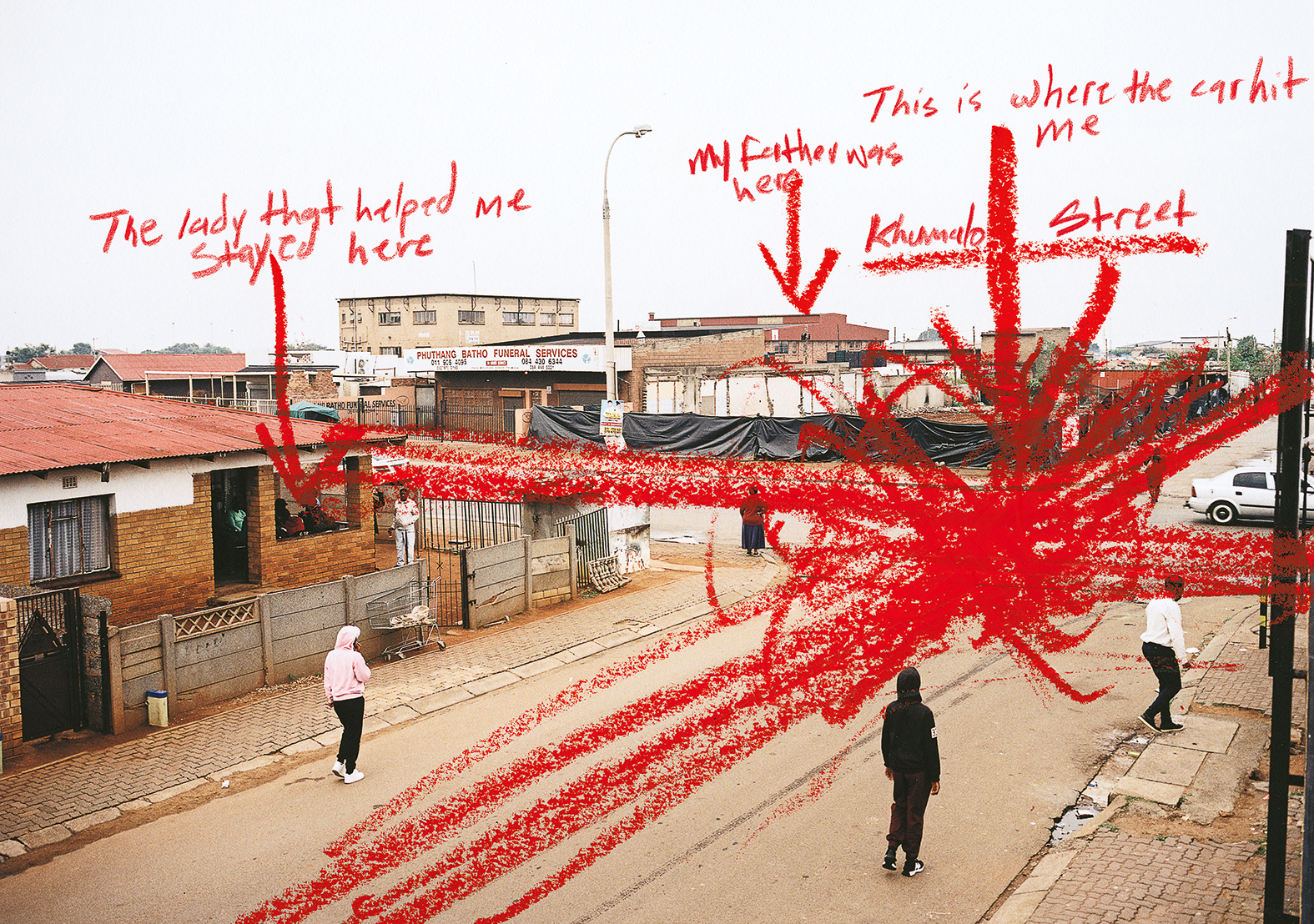

In 2001, when Lindokuhle Sobekwa was 6, his sister disappeared. Ziyanda, 12, witnessed her little brother being hit by a car in Khumalo Street, Thokoza, a township east of Johannesburg. In Lindokuhle's blurred memories, a young woman was standing over him after the hit – but he is not sure if that was Ziyanda. With a broken spine, he was carted off to the hospital, where his recovery took three months. Once back home, Ziyanda was nowhere to be found. It was 11 years before Lindokuhle was able to reunite with his sister.

This dramatic event is part of a pattern of disappearances and disconnect. Anyone who knows a little of the history of apartheid South Africa knows the extent to which that system erected walls and laws, rules and buffers between different populations. But, perhaps even more ruthlessly, disruption struck within families, communities, and neighbourhoods. Fathers disappeared into mines, mothers into nanny cottages in the backyards of white households, far away from their families. People were relocated into homelands and slums. While 2001 was seven years after the official abolition of apartheid, the legacy remained – and still remains – abundantly visible in a landscape full of fault lines.

The recently released photo book I carry Her photo with Me is a penetrating account in images and notes of Lindokuhle's search for his sister. “Just like my mother, I began a quest searching for my sister's footprint who had disappeared for a decade,” he writes. “On this journey, I discovered that this was not only finding out about my sister's disappearance, but also part of myself that I had lost in the process. I began using a diary to reflect about how I felt at that time. I started using photography to search for answers to heal, to make my family talk and end the cycle of people disappearing in my family.”

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from I carry Her photo with Me (MACK, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Apartheid represents a history of numbers: over a hundred racist laws, eleven million arrests of people who violated them, 69 deaths in Sharpeville, March 1960, over 600 deaths in Soweto, June 1976. So many political prisoners, torture chambers, bulldozed multicultural neighbourhoods, political trials, executions, kidnappings, banned books. These are data that make you shudder, just as statistics on the Holocaust or slavery do. But the impact of one story, one testimony can hit so much harder than the whole sum of atrocities.

I carry Her photo with Me is such a story.

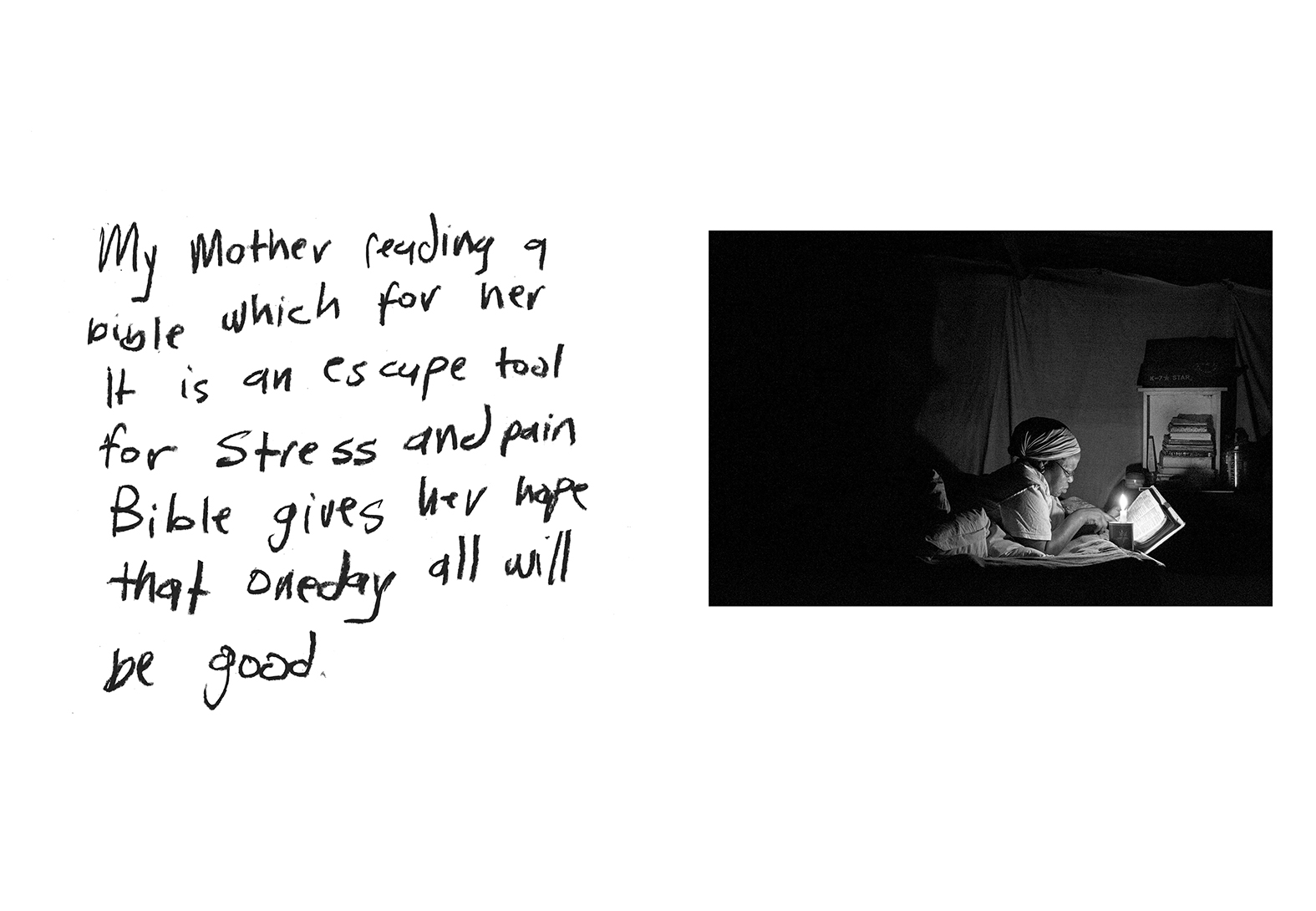

Sobekwa's book shows, much less than the footprints of grief, the beauty of a world from which his sister had been retouched away for 11 long years. The book opens with the only family snapshot in which Ziyanda (“Her photo”) is visible. In that photo, she makes a sign attributed to the 28s with both hands, a notoriously brutal gesture. Then we see her friends, graffiti, the portrait of Marilyn Monroe on a cooler box, the windblown sand of the dirt road, the trees and rugs that brighten the meagre shelter. And then by candlelight, “My mother reading a Bible which for her is an escape tool for stress and pain. Bible gives her hope that one day all will be good.” We see the winter landscape in the countryside where Ziyanda grew up with her grandmother. There is the tent camp set up after a fire destroyed Lindokuhle's neighbourhood, and then the new house that was completed after years of waiting (“A place we call home”).

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from I carry Her photo with Me (MACK, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

The heart of the book includes a spread of Khumalo Street, showing the spot where the car hit Lindokuhle and the home of a local resident who came to the rescue. The crayon used to make the notes in the photo seems to overwrite the image that haunted this street in the latter days of apartheid. A civil war was fought here, between supporters of the ANC and Inkatha, fuelled by the police. The street was known in the One- Day-Flies-coverage as the “deadliest in South Africa.”

But it is also the street where a boy broke his back and exchanged last looks with his sister. And where a woman lives, who cared for the boy and called an ambulance.

In 2013, Lindokuhle's mother learned by chance that her missing daughter was believed to be living in a hostel not far from the family's shack. Lindo found his sister, deathly ill, scars on her back. She returned home, forbidding Lindo to photograph her. Sometime later, they found Ziyanda with foam coming out of her mouth. They took her to the hospital, where she died. A tragedy, but after all these years, also a story of reunification.

In her outstanding essay “Tracing an Absence” – appropriately inserted as a separate section in the photo book – art critic and professor M. Neelika Jayawardane recalls meeting Lindokuhle Sobekwa in 2018 at her home. It is on this occasion that the photographer showed her a small notebook. For the first time, she read texts about Ziyanda, about the guilt that haunted Lindokuhle after her disappearance. Was it his fault? Had she lashed out after he ran toward her without paying attention to traffic? The drama was never discussed in the family, he told Jayawardane. He doubted he could make a visual record of what occurred, of “something that no one wanted to speak about, which he himself struggled to put into words.” And, “He could not make the voids of Ziyanda's life emerge from the shadow spaces.”

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from I carry Her photo with Me (MACK, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

As time passed, Sobekwa saw through the lens of his camera the outlines of what would become a deeply impressive testimony, helped by the bits and pieces he picked up along the way. The antiretrovirals hidden in her clothes. The sneaky visits she made to family members over the years. The various corridor names she appropriated: Zodwa, Lerato, Nthabiseng (alternately Xhosa or Zulu, depending on her company). He followed routes Ziyanda walked. Handled a camera with expired films. “You need to push it, over-expose it,” he explained to Jayawardane. His journey also took him back to the Eastern Cape, his ancestral homeland.

Thus a family tree developed and he saw, in Jayawardane's words, “the fragmentation caused by colonial taxation and land expropriation, by the extractive processes of gold and platinum mining, and by apartheid era urban planning that served the Randlords' wealth.”

It is this family tree that, in the end, “brought the bodies back, returned the disappeared."

Lindokuhle Sobekwa (b. 1995, Thokoza) trained at the renowned Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg after a photography course Of Soul and Joy from 2015.

I carry Her photo with Me is published by Mackbooks. ISBN 978-1-915743-31-2.

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.