It is up to your imagination to interpret the South African photographer’s quest into exile.

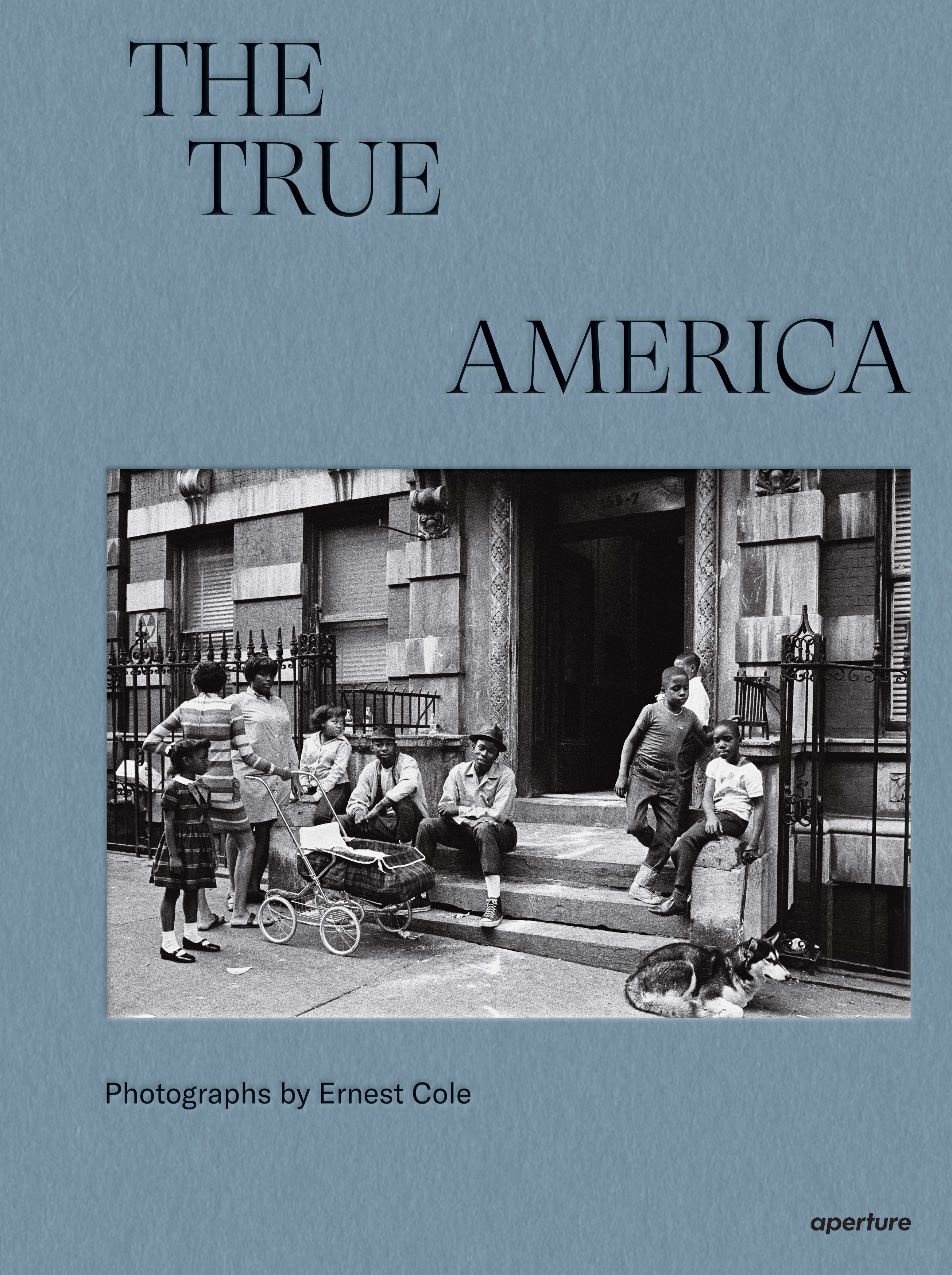

The True America, a recently published book of works by South African photographer Ernest Cole, lacks captions. There is no indication of time or place. The book only distinguishes between the first section, which is set in New York (remarkably with one section in colour), and the second section about beyond – California, Ohio, Alabama, and Mississippi. Cole, who travelled to the United States in 1966 and could never return to his native country because of an official banning order, travelled through all these regions and built a body of work that showed the true face of America, according to the book's compilers. But what do we see?

The book title alludes to The House of Bondage, published shortly after Cole’s involuntary exile. I consider this book of photography my richest possession. It shows the horrifying practices of apartheid: overcrowded migrant trains, dilapidated schoolrooms, abject poverty, slums, humiliation. House of bondage, of slavery. The book, which includes essays and captions, is above all, in the words of journalist and scholar James Sanders, “an assault on apartheid.”

Raoul Peck, lauded filmmaker, including of the impressive Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro, and author of one of three essays in The True America, sees another indictment in the selection from the more than 40,000 images Cole shot in America. “It seems that most damaging for him was the discovery that even in the most cosmopolitan city in the world… there was misery, racism, ignorance, and solitude,” Peck writes. He sees Cole as a chronicler of injustice and callousness. Peck attributes the solitude mainly to the feeling of being displaced, to which Cole must have fallen prey. “The feeling of not quite belonging anywhere, and simultaneously feeling free and emboldened to reclaim a place in that foreign space... Exile gnaws at the flesh, piece by piece, stripping it to the bone… Exile is a demanding and merciless mistress… To be out of a place is a curse and a death sentence. The only way out is to focus your energy on relentless creative quests.” Tragically, these quests could not prevent Cole from dying of cancer (at 49 years young) in early 1990, the year when a new dawn might make an eventual return to South Africa possible.

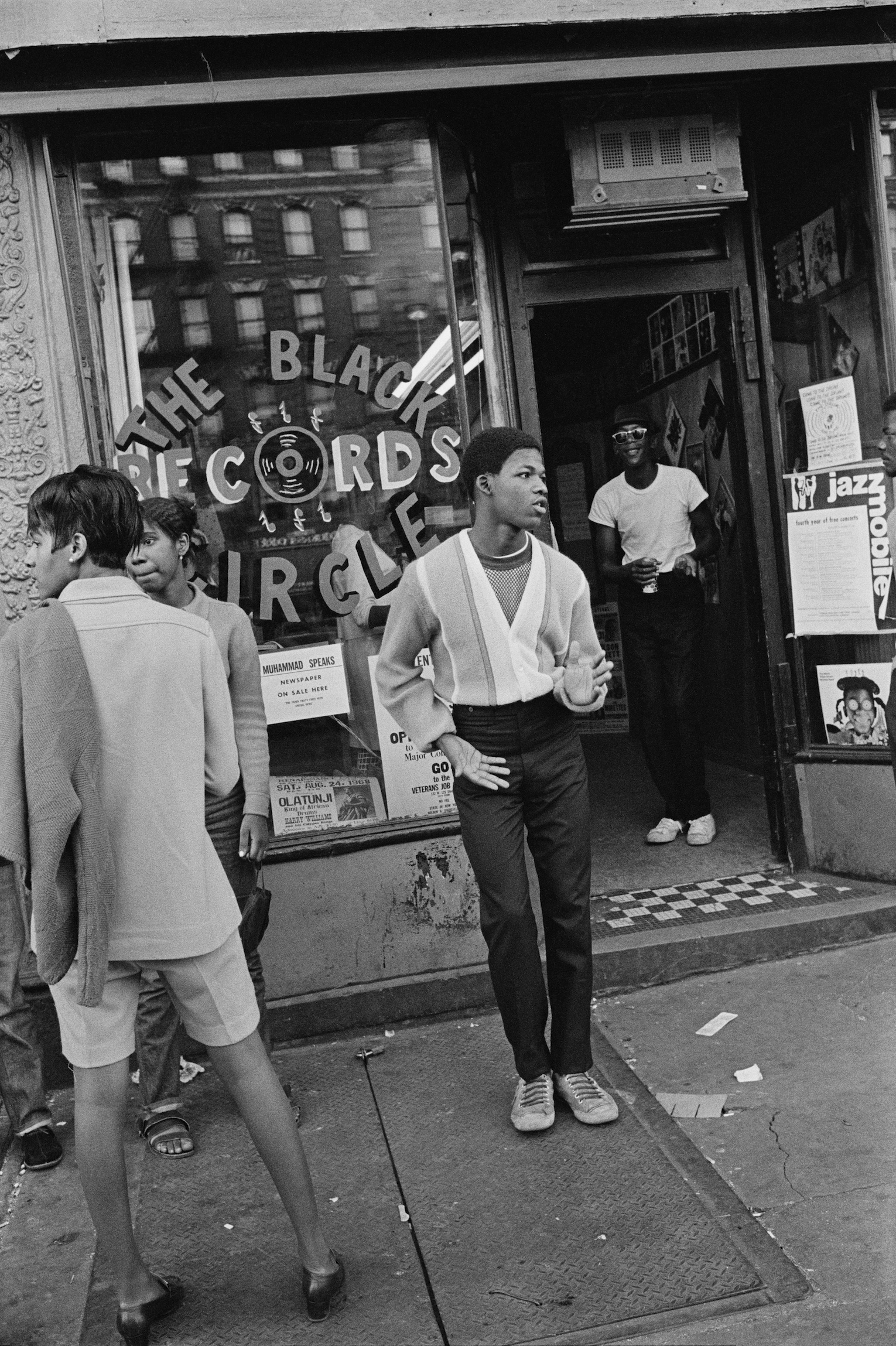

Peck’s sombre account contrasts with the other two essays that precede the photography. The authors, James Sanders and Leslie M. Wilson, see something different, something more multifaceted, in Cole's work. Sanders writes: “(Cole) was clearly fascinated by the cultural revolution that was happening in New York.” Referring to the ubiquitous sexual references and shop windows full of pornography in the streets, Sanders continues, “After South Africa, this free for all must have felt bizarre.”

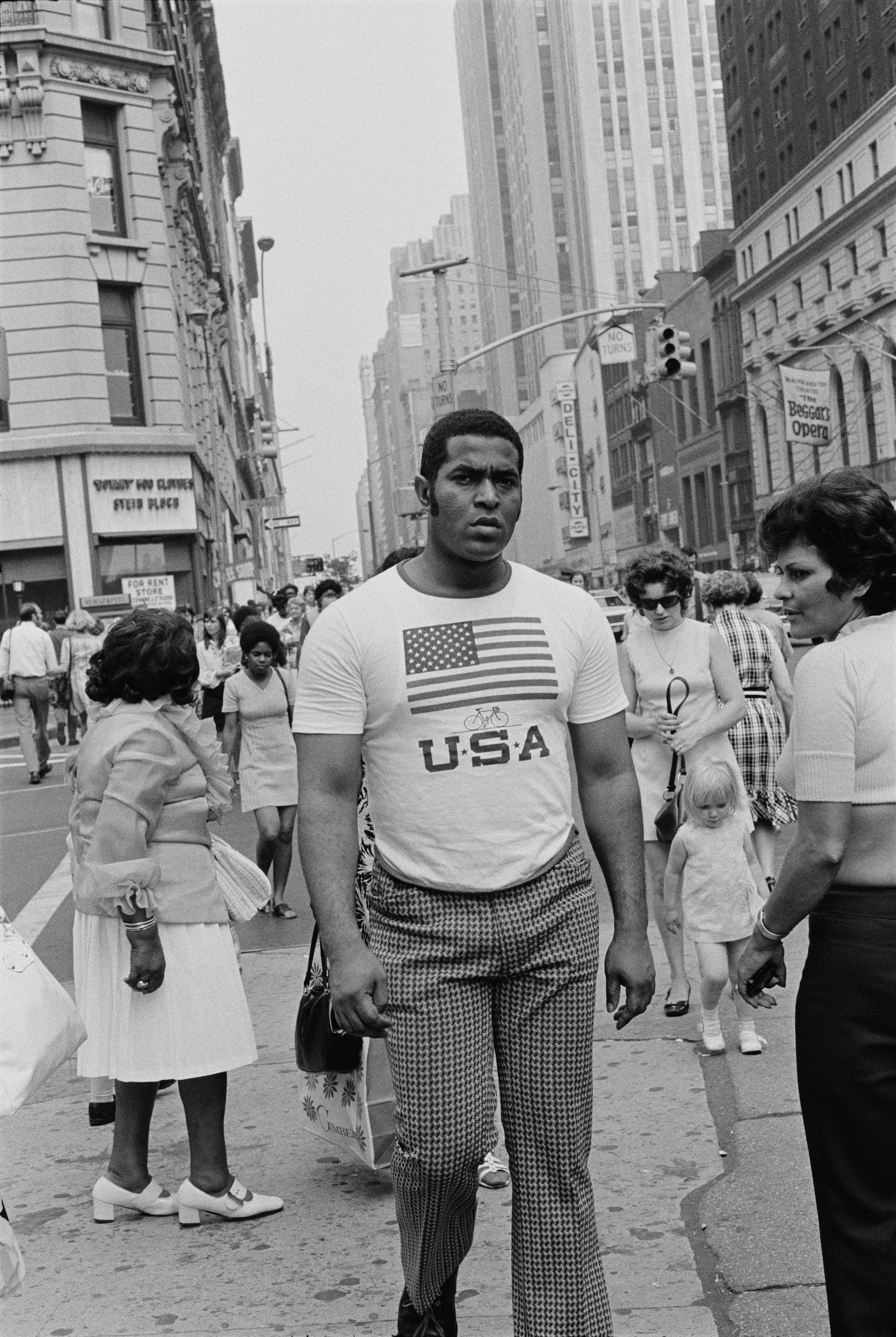

African-American art critic Leslie M. Wilson also recognises more dimensions in Cole’s work. “He was interested in the sheer density of people in the heart of New York – their fashions, their peccadillos, their protests,” she writes. “Cole (is) taking advantage of a greater freedom to get closer to people in New York than he could in South Africa.”

Leafing through the book again and again, I feel a stronger kinship with Wilson and Sanders’ observations. The book does include images of segregation, ghetto life, poverty and exclusion, especially in the second part, titled The Situation in this Country: Travels in America. But surely the inequality Cole shows is just as clearly shown by the many protests against it: the marches, the bookstore windows with subversive reading, the murals of Malcolm X, Carmichael, King, the picket lines. They are images of protest, so unthinkable in the South Africa of the years leading up to Cole’s departure. They are images full of expectation. In the 1960’s, with the leadership of the resistance movement largely driven into exile or being deported, it is this hope for change that South Africa lacked at the time. What became of that hope is another story.

The puzzled but mostly curious gaze of the rather conservative Catholic man that Cole was speaks from his images of overt sexuality, images of drag queens or two boys kissing at the fence of the New York subway. These are images unthinkable in the South Africa of his youth. This exploratory gaze that was only able to reach maturity far from home, and under extremely difficult circumstances.

The True America: Photographs by Ernest Cole is published by Aperture and available at aperture.org. Book design by Oliver Barstow.

Watch this ZAM video with Ernest Cole’s nephew Lesley Matlaisane at the FOAM exhibition, 2022.