Benoit Collombat and Grégrory Mardon revive the investigation into the murder of a South African anti-apartheidactivist in Paris in 1988.

An activist killed not so much for the stories she might tell in the present, but for what she might reveal in the future, writes Leonard Cortana in a review of a recently published graphic novel on the assassination of South African anti-apartheid fighter Dulcie September.

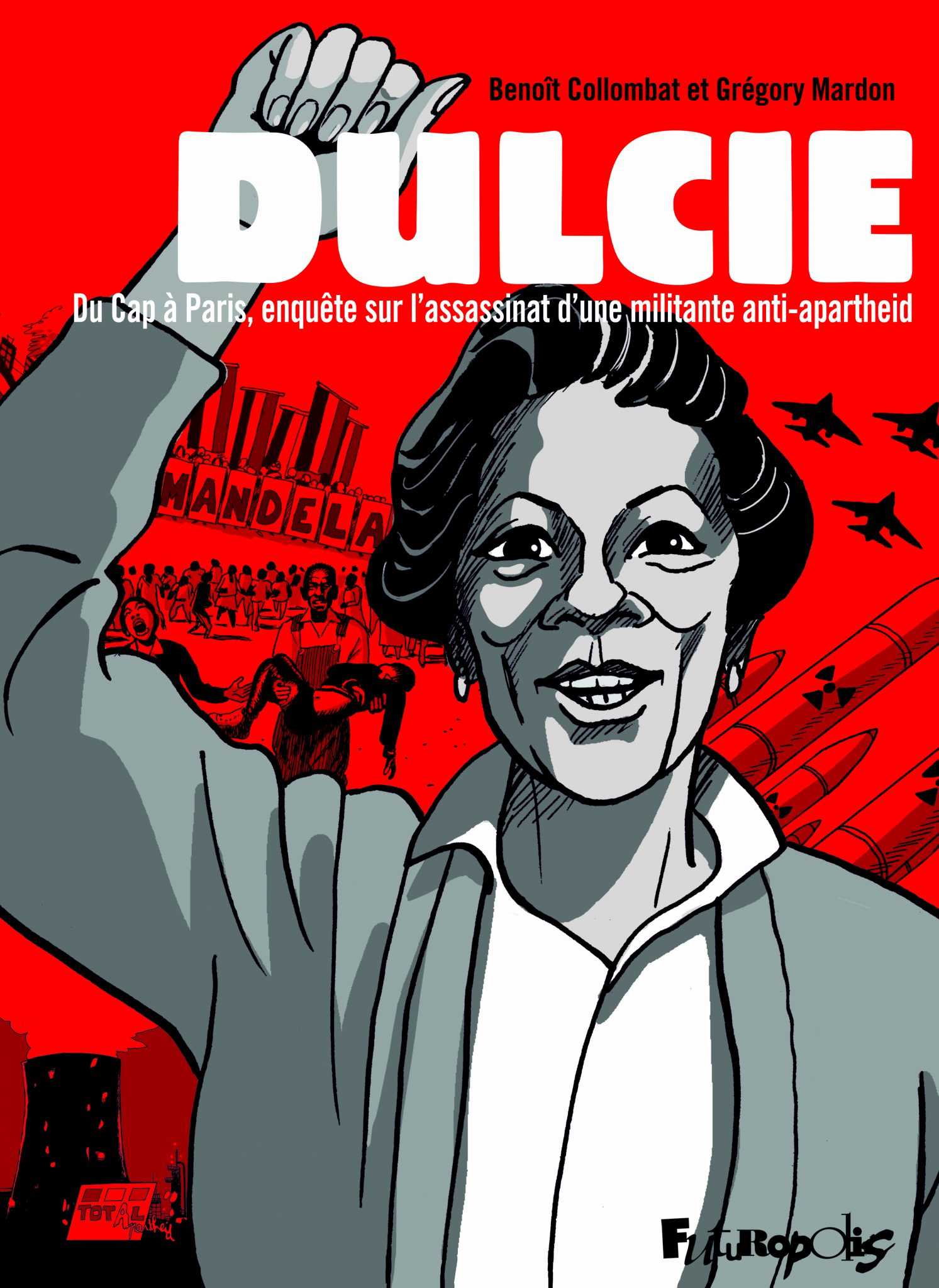

Thirty-five years after the murder of Dulcie September on 29 March 1988, and following the very recent failed attempt to reopen her trial in France, Benoit Collombat, a journalist with Radio France's investigative unit, and Grégory Mardon, a cartoonist, have published the graphic novel Dulcie from Cape Town to Paris, an investigation into the murder of an anti-apartheid activist. The 300-page opus goes behind the scenes of a ten-year investigation into the murder.

Who was Dulcie September?

A little-known, and sometimes forgotten, figure in French and South African history, Dulcie September embarked on a teaching career at a very young age. Categorised as a “Cape Coloured”, she witnessed the disastrous consequences of the Bantu education laws that instituted segregation in the South African school system. In addition to teaching, she became involved in activism with the Yu Chi Chan Club, a Maoist-inspired group that later became the National Liberation Front (NLF).

Just under a year after joining the Front, she was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison. When she was released, she was banned from public life, could no longer move freely around the country, and could no longer practise her profession as a teacher. She opted for exile, first in England and then in Lusaka, Zambia, where she became close to the resistance movements of the South African diaspora. At the end of 1983, she was appointed head of the Paris office of the African National Congress (ANC), Nelson Mandela's party, after President François Mitterrand authorised the liberation movement to set up office in France. In this position, which she held until her death in 1988, she led awareness campaigns and travelled throughout France to talk about the experiences of black communities in South Africa under a criminal regime. She appeared on French television, where she was asked the same question over and over again: should the ANC be considered a terrorist organisation? She replied frankly that “the real terrorists are the racist apartheid regime in South Africa and their segregationist laws.”

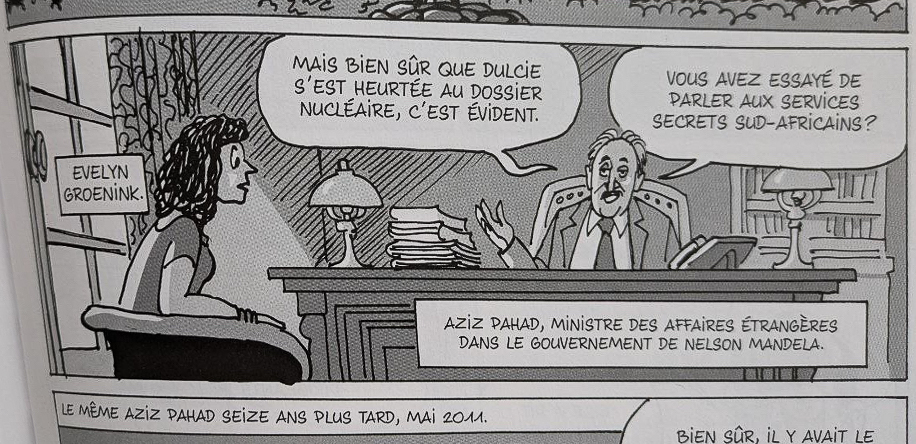

ZAM's investigative editor Evelyn Groenink played a prominent role in exposing the backgrounds of the Dulcie September murder. More about her investigation here

Alongside her information campaigns on apartheid, Dulcie September investigated arms trafficking and military and nuclear collaboration projects carried out by French companies (which were protected by networks at the top echelons of the state). Her investigative work and encounters caused a stir. The book posits that she knew too much at a time when the apartheid regime was losing steam under the weight of global economic boycott campaigns. In 1988, the year of her assassination, ANC leaders began to prepare their economic partnership with companies that were already collaborating with the apartheid regime. Watched and followed, Dulcie September tried in vain to obtain police protection. She was assassinated just a few months before the French presidential election marking the start of François Mitterrand's second term in office.

Although September’s story has been largely omitted from the official history of South Africa and France, many tributes have been paid to her. Shortly after her death, Jean-Michel Jarre dedicated a song to her, performed on stage by a choir of African women. In March 2019, the NGO Open Secrets (whose mission is to hold the private sector to account for economic crimes and human rights violations during apartheid) launched an eight-episode podcast entitled Who killed Dulcie? A year earlier, the director of Open Secrets, Hennie van Vuuren, another key character in Collombat and Mardon's comic strip, had exposed the transnational networks of crime and arms sales in his over 400-page opus Apartheid Guns and Money, in which he devotes an entire chapter to the assassination of Dulcie September.

In 2021, the movement in support of September continued with the release of the documentary film Murder in Paris by South African director Enver Samuel. The film retraced parts of the activist's life and explored several leads to her murder. An awareness campaign and a petition were launched online under the hashtags #justicefordulcie and #mercidulcie. The film is being screened and followed by discussions in South African schools to bring her – equally contemporary – struggles to life for the younger generation.

Dulcie September's struggles are at the heart of the plot

The graphic novel follows in the footsteps of these tributes and is an act of restorative justice in several respects. First of all, on the French side, most of the archives surrounding the case are still sealed, preventing Dulcie September's family from having access to her notebooks and work. Collombat and Mardon take care to highlight September's investigative and writing work, whether reconstructed or recounted by her close collaborators. Jacqueline Dérens, a former anti-apartheid activist and founder of the Association Rencontre Nationale avec le Peuple d'Afrique du Sud (RENAPAS), is one of the main protagonists of the book. She was one of September's closest collaborators during her stay in France and, as Colombat recalls in numerous interviews, she was the trigger for the book to be published. In 2013, she published a biography of September tracing her political involvement from South Africa to her term of office with the ANC in France.

In the graphic novel, Dérens recalls the many pressures September was subjected to on a daily basis and the precautions she had to take whenever she travelled. As the pages turn, we can only admire September's unfailing commitment to her cause: the liberation of the people of South Africa.

The book reminds us that the voices of activists cannot be silenced. These stories must be documented with those who were close to them in their struggle. The intrigue surrounding the crime and the speculation about those who wanted to silence her forever are secondary.

In March 1988, September's murder made headlines in the press and on television news, at a time when the French presidential election campaign was already in full swing. However, consultation of the archives of the Institut National de l'Audiovisuel (INA) shows that no television channel took the time to retrace Dulcie September's career or her work – reducing her to a statistic in the long list of murdered people who fought the ANC's fight. Yet September was the only member of the movement to have been murdered outside the African continent and, what's more, she was murdered in Paris, a highly symbolic location for European diplomacy and the promotion of human rights.

These issues also remind us of the role of women activists in a rather masculine and sexist anti-apartheid movement. The ANC's triumphant history has focused more on men's acts of bravery, giving less prominence to the struggles of many women who denounced violence within the party. Many of them showed as much courage as September and even lost their lives, as did other exiled women such as Ruth First and Jeanette Schoon.

A diplomatic post-colonial history

France's commitment to the United Nations in 1977, when it signed Security Council Resolution 418 to isolate the apartheid regime politically and economically, did not put an end to economic relations between the two countries.

The graphic novel works to dispel the idea that France was immediately won over to Nelson Mandela's cause. France, which in 1996, during his world tour, celebrated Mandela with great pomp after his election as president of the new rainbow nation, also hid, as far as possible, any trace of its past complicity with the apartheid regime. Some of apartheid’s political and economic supporters were concealed, along with groups in the National Assembly and the European Parliament who openly affirmed their political and moral allegiance to the apartheid regime. Take, for example, the Courrier Austral Parlementaire, an episodic publication considered to be the organ of the pro-apartheid lobby in France. These supporters, the graphic novel shows, were found well beyond the right-left divide. Part of a speech delivered by September on 31 January 1988, in which she confronted left-wing supporters at the Congress of the anti-apartheid movement, close to the Socialist Party, is faithfully transcribed. In front of those who were to be her collaborators, she was indignant: "This is neither the time nor the place for me to have a public confrontation, but the fundamental question I am asking here, to all of you, is the following... does the anti-apartheid movement support the ANC as the movement for the liberation of the South African people recognised as such not only throughout the world, but above all by the South African people themselves?” September was aware of the double standards at play, and of the need to point out that she had to remain the primary interlocutor in the dialogue between France and South Africa in preparation for a post-apartheid democracy.

However, the book underlines that these relations went much further than strictly bilateral co-operation between the two countries. Like a spider's web that stretches throughout the story, relations with South Africa reveal how French economic forces and institutions maintain privileged relations with African and European countries that serve as relays. Unearthing a little-known archive, Collombat reveals an interview with Aimé Habib, a member of the Reunion Communist Party who worked closely with Paul Vergès, founder of the same party who was a major financial supporter of the ANC. Habib explains that when Vergès was elected MEP, he was given the task of investigating the use of Réunion's ports as pivots for circumventing the embargo. Valves used in French nuclear power stations were stamped with Reunionese products to be transported safely and with impunity to South Africa.

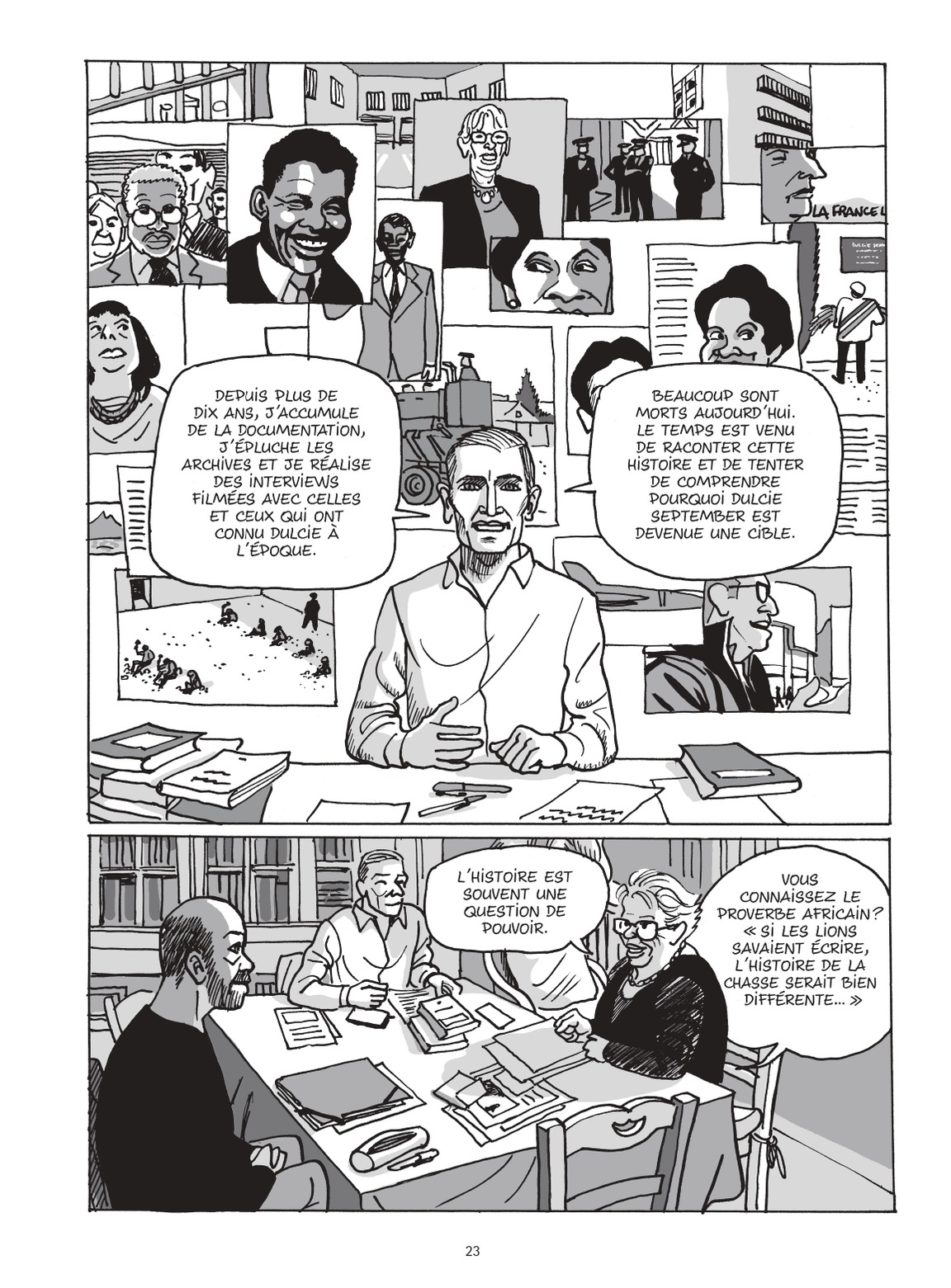

This is undoubtedly one of the book’s greatest strengths. Collombat, who becomes the narrator of this investigation, immerses us in the intimacy of his meetings with all these players. Oscillating between a didactic and mischievous discourse, and showing, not without humour, the evidence of bad faith of some of the witnesses, Collombat and Mardon make this diplomatic post-colonial story a human-sized tale. Readers share their emotions and their epiphanies, as well as their annoyances. This approach lends strength to the narrative, as readers are never distanced from the investigation; on the contrary, the angles chosen make them full members of the conversation. It's worth noting the irony that shines through in many of the panels – as in this exquisite drawing of Russian dolls to represent the French friendly associations with the South African regime. This irony undoubtedly served the authors as a bulwark against the blatant lack of humanity shown by French politicians and industrialists in the face of the seriousness of events in South Africa and the primacy given to money over everything else.

Recreating archives to compensate for the lack of justice

The investigation focuses on a number of protagonists, leaving the reader free to form their own opinion. The story is framed by the artist's meticulous reconstruction of the archives that lay dormant in the state’s sealed, classified boxes. These archives – maps, letters, emails, press releases, newspaper extracts, telephone conversations and text messages – are a testament to the exemplary rigour and seriousness of the investigation. In contrast to the botched investigation by the courts at the time, Collombat and Mardon refuse to accept any approximations, and verify the information with a fine-tooth comb. With great inventiveness, they use all the creative possibilities offered by comics to lay out the evidence for the reader, who becomes a juror in an imaginary trial where the untouchables take the stand to explain themselves. In the second part of the story, the reader will enjoy being immersed in the psyche of the author-investigator Collombat who, from testimony to testimony, advances in his search for the truth.

The black-and-white and chiaroscuro artwork places the investigation in the aesthetics of inter-war film noir. The many scenes of encounters in the streets and cafés of Paris also place the city of light at the centre of the grey areas of this investigation, which has officially been shelved.

The book opens with the murder scene, accompanied by excerpts from the autopsy, removing what could have spanned dozens of pages in other, more racy stories. Collombat and Mardon set out the ethics of their commitment to the case, and the narrative gradually opens up. They question those who could have ordered the murder and who had every interest in silencing September's voice. The possibility of a crime of passion, a classic feminicide, is raised for a while. An activist is killed not so much for the stories she might tell in the present, but for what she might reveal in the future. The uncompromising Dulcie September was also to be an obstacle in the construction of post-apartheid South Africa. That is the lesson to be learned from this magnificent book.

As the pages turn, we witness a war of rewritings of history, of those who had to reinvent themselves so that their reputation and legacy would not be hampered by the indelible stains of an unethical collaboration with the apartheid regime. The difficulty of reopening the archives and the trial for Dulcie September undoubtedly stem from this.

Today, the hope remains that other books in the vein of this one will honour the work of activists who also lost much in defending their ideals of justice and equality. This graphic novel is another step towards ensuring that September's story exists in the collective memories of France and South Africa, which are forever intertwined. The book urges the French justice system to finally respond to the appeals lodged by the families and loved ones so that, in their lifetime, the many grey areas that still hang over the murder of Dulcie September can disappear.

"Dulcie. Du Cap à Paris, enquête sur l'assassinat d'une militante anti-apartheid” by Benoît Collombat and Grégory Mardon.

This review was first published in Revue Alarmer